Select Other Languages French.

Annemarie Jacir’s new film is big-tent entertainment, accented by a critical history of Anglo-Zionist collusion between the wars. Palestine 36 commences its theatrical run in the UK and Ireland on 31 October.

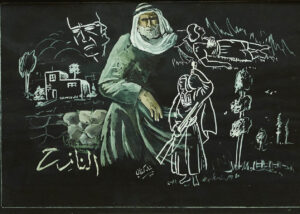

Before the Nakba: Palestine 36 and the History of a Forgotten Revolution

A delegation of bourgeois ladies has gathered outside the headquarters of Arthur Wauchope (Jeremy Irons), the High Commissioner of British Mandate Palestine. They’re chanting “Palestine is not for sale!” When Wauchope agrees to see them, one demonstrator asks why Palestinian villages are punished every time anti-Zionist rebels attack the British army.

“Because, as you know better than anyone,” Wauchope replies, “the Arab holds the community in higher value than the individual.”

It’s a curious moment in Annemarie Jacir’s Palestine 36. The ladies don’t contest the Englishman’s depiction of “the Arab.” Is that because these nascent feminists recognize a distasteful truth underlying the occupier’s orientalism? Perhaps they’re simply appalled at the casual racism with which Wauchope dismisses their advocacy.

Having lived through Israel’s two-year-long ethnic cleansing campaign in Gaza, some filmgoers in late 2025 will note that collective punishment was as much a tool of British occupation as it is for the Israelis. This seems to be one goal of Jacir’s ambitious new film.

Palestine 36, which has commenced its theatrical run in London after its UK debut at the BFI Festival, recounts the early months of The Great Revolt of 1936-39, Palestine’s first national uprising. For various reasons, this most pivotal moment in Palestinian history has been largely occluded from international consciousness, eclipsed a decade later by the Nakba (catastrophe).

The problem with rooting Palestine’s founding story in the Nakba is that it foregrounds catastrophic defeat at the expense of obscuring both British imperialism as the harbinger of Zionist settler-colonialism, and the ‘36-39 Thawra as a crucible of national unity.

Jacir’s film sets out to dramatize how Britain’s Palestine Mandate laid the legal, administrative, and tactical groundwork for the Zionist state and how these policies impacted Palestinian identity. This task is daunting — both for the scale of the story and for the filmmaker’s defiance of filmmaking gospel. Mainstream cinema is intolerant of critical history and, unlike Wauchope’s “Arab,” has made a fetish of the individual.

Dramatis personae

Opening in Jerusalem, the film first introduces Yusuf (Karim Daoud Anaya), who’s employed as a driver by the bourgeois Atef family. Amir Atef (Dhafer L’Abidine) is well off and well educated, as is his wife Khuloud (Yasmine al Massri), a journalist and Mandate critic. Yusuf arrives at their house looking for Amir, but is intercepted by Khuloud. Long-stemmed cigarette in hand, dressed in her husband’s tarboush and trousers, she demands the latest news from the countryside.

Yusuf is at the center of the film’s ensemble of characters in Jerusalem and his village, Al-Basma. A community of Christians and Muslims not far from Jerusalem, it is modeled on the historic village of Al-Bassa, the site of a British massacre in 1938 and ethnic cleansing by the Haganah in 1948. Yusuf has a chaste love interest in Rabab (Yafa Bakri), a no-nonsense young widow who lives with her pre-teen daughter Afra (Wardi Eilabouni) and parents, Hanan (Hiam Abbass) and Abu Rabab (Kamel El Basha). The mother-daughter pair of Rabab and Afra are introduced walking alongside the British-built Kirkuk-Haifa oil pipeline, where they pause for a spell to puzzle over the European immigrants through the barbed wire fence they’ve erected around their settlement.

“Why do they come here?” Afra asks.

“Because their own countries don’t want them,” Rabab replies.

Afra has a chaste friendship of her own with Karim (Ward Helou), the son of the village priest, Father Bolous (Jalal Altawil). When he’s not with Afra, Karim divides his time between altar boy duties and making shoes in the Jerusalem souq. At one point he presents Afra with a pair of hand-made shoes, which she wears but impatiently kicks off when she wants to play.

Finally, there is Khaled (Saleh Bakri), not from Al-Basma but a stevedore at Jaffa Port. When a militant on his crew tries to recruit him, Khaled replies that his only interest is making money to send to his family. Squeezed between the port authority’s preferential treatment of Jewish workers over Palestinian laborers and the Mandate’s tolerance of the Zionists’ illegal arms shipments, he eventually relents and joins the rebellion. Khaled is next seen, rifle in hand, boarding a train to collect voluntary contributions to support the resistance.

Jacir’s depiction of her Palestinian characters is sympathetic but not romanticized. She doesn’t imply that this part of Bilad al-Sham was a paradise before the British replaced the Ottomans. Her characters are creatures variously constrained by tradition, want of worldly sophistication or naïve idealism. One of the motifs woven into the plot is how Palestine’s leadership could not see that the rules had changed — whether village mukhtars who believe they can reason with the colonists, as they had defused disagreements with neighbors in the past, or the urban elite of traders and landowners who try to do business with Zionism.

Palestine 36 was shot during the genocide in Gaza — a saga in itself — but there are no Zionist characters in this film. News reports sometimes mention Irgun terrorist attacks and, at a ceremony launching Wauchope’s politics-free Palestine Broadcasting Service, the High Commissioner wrangles an Oslo Accords-style handshake photo-op between a bearded kibbutznik and gent in a kuffiyyeh. Officially, it’s still the English enforcing the occupation in 1936.

Several scenes suggest that the squaddies demanding to see Palestinian travel permits are as prone to thuggish behavior (lewd sexual innuendo, highway robbery) as gunmen anywhere, but not all the British characters are villains. Wauchope himself is less diabolical than ineffectual — a uniformed bureaucrat micromanaged from London. Wauchope’s assistant, Thomas (Billy Howle), is a decent fellow, sympathetic to the Palestinian predicament. He becomes Khuloud’s principal source on Mandate intrigues, but he doesn’t have the authority or disposition to influence policy.

A far more toxic Brit on the ground is Captain Wingate (Robert Aramayo). The brutal face of millenarian Christian Zionism, he believes some deity wants the ancient state of Israel reconstituted, and that Zionism is the best hope for maintaining imperial interests. The only English character presented as comfortable speaking Arabic, Wingate rhapsodizes the bountiful land of Palestine, then dynamites Palestinian houses. It’s Wingate’s men who participate in the Night Squads — arbitrary Anglo-Zionist raids on sleeping villages — and whose deadly raid on Al-Basma recreates the historic British massacre in Al-Bassa.

Representing Palestine

Jacir has been depicting facets of the Palestinian condition since her 2003 debut Like Twenty Impossibles. Her stories are marked by outrage at the occupation’s impudent criminality while her visual language has leaned toward indie-flavored cinematic realism. Palestine 36 marks the first time she’s choreographed gunplay, but the issue of militancy simmers in all her feature films.

Her debut feature, 2008’s Salt of This Sea, a genre hybrid that opens upon the story of a young Palestinian-American’s “return” to the West Bank, has nothing to do with armed opposition to occupation. Yet militancy is smuggled into the plot when it morphs into a heist picture-cum-road movie.

When I Saw You, 2012, follows a little boy who, displaced by the 1967 war, flees a Jordanian refugee camp. Intent on returning home, he instead finds shelter in a training camp for leftist fida’iyyin.

Wajib (Obligation), from 2017, is, in part, a comic tour of contemporary Nazareth. Following a squabbling father and son hand-delivering wedding invitations, it delicately probes the rifts between generations and those within and outside the territory of ’48 Palestine. One of the things they quarrel over is the PLO, whose resistance, the father sneers, ultimately abandoned both the refugee community and Palestinian citizens of Israel, accomplishing nothing.

Aspects of Palestine 36 mark a departure from Jacir’s earlier work. First, the film is particularly engaged with both history and the conventions of historical drama. Balancing the two is a significant challenge, since Jacir has set out to make a film that speaks to a wide audience — in the Arab world as well as the West. This engagement affects both narrative and formal aspects of the film.

When I Saw You, for instance, is set in the aftermath of the Naksa (“setback”) but, like all Jacir’s previous features, it is an intimate film focusing on a compact group of characters. It doesn’t dwell upon armed resistance, but rather uses it to premise a story focusing on the cultivation of community.

Palestine 36 is, by contrast, a big picture with an eventful story. The importance of historical veracity is evident from the opening frames. The film doesn’t commence with a conventional widescreen establishing shot, but with a montage of scenes depicting life in historic Palestine. All this footage has a square aspect ratio and the grainy texture and saturation you might associate with archival film. That’s exactly what it is — colorized, otherwise unaltered, black-and-white reels supplied by the archives of such institutions as AP, BFI, the Imperial War Museums, and Getty.

These interludes crop up throughout the film, as the widescreen fictional story gives way to square-framed Mandate-era footage. The effect is reminiscent of pages of archival plates or other images supplementing the text of a monograph. The function of these nonfiction interventions is not simply aesthetic. Historic footage of Palestinian life in cities and villages, on the coast and in the countryside, serves to supplant historical fictions, popular in Israeli narrative, about the absence of an indigenous Arab population of Palestine.

The formal interjections are frequently preceded or followed by title cards, whose intertitles may situate the location and date of the action or else suggest chapter titles — an age-old fixture of historical drama.

But is it cinema?

An absorbing web of fictional narrative drives the film forward. Its stories are diffuse — appropriate given the characters’ spatial and social separation. Some of the popular cinema conventions that Jacir embraces for the film, however, may irritate a few viewers for their lack of subtlety.

The score, by sound artist Ben Frost, is unobtrusive for the most part, but does tend to swell to symphonic extravagance to accompany dramatic sequences. Some scenes may also seem a bit over-written, by indie standards. One nicely engineered subplot follows the gradual estrangement of a married couple, as one of them hopes to leverage a political career from doing business with the occupation. The breakup itself is admirably concise and silent, but the wife’s telegraphic final gesture will seem needlessly melodramatic for some.

Viewers fearing that Jacir’s version of historical fiction emulates the aesthetic of Arabic and Turkish musalsalaat need not worry. It’s true that characters’ in-frame relationships are uniformly G-rated, but Jacir’s work has never been known for extended sequences of sweaty grappling, à la Abdellatif Kechiche. Character interactions are economically written and acted, leaving much in these relationships unspoken.

Big-tent cinema can accommodate good writing and acting, and both can be found in this film. Most of the film’s best-loved talent — Jeremy Irons, Liam Cunningham (playing notorious anti-insurgency tsar Charles Tegart), Hiam Abbass and Kamal El Basha — are playing supporting roles. It may seem a waste, but by casting such engaged professionals for these parts — rather than well-meaning amateurs — Jacir has secured performances that linger long after the credits roll.

One case in point is the tireless stream of cigarettes that Irons lights and steers to Wauchope’s gob while he’s in the frame. Just as memorable is the little speech that concludes the High Commissioner’s audience with the petitioning ladies of Jerusalem — not least the unctuous smile contorting his face after rehearsing the occupation’s line on “racial tolerance.”

A significant subplot follows the movement of a hand-crafted Ottoman pistol, a pre- World War I relic that finds its way to the house of Hanan and Abu Rabab. This “Turkish beauty” remains in play until the film’s dénouement. En route, Jacir stages two strong scenes in which adult characters separately counsel children on the wages of vengeance.

In one of these, Afra steals into her grandparent’s empty sitting room, prises the pistol from its hiding place and admires it, as Hanan surreptitiously watches from the doorway. Most of Hanan’s screen time is in ensemble, but here Abbass is alone in the frame with novice Wardi Eilabouni.

“I can show you how to use that,” she remarks, nodding dismissively at the weapon the girl has hastily re-hidden, then proceeds to remind viewers of Abbass’ skill in stealing any scene that gives her a few minutes to act.

Robert Aramayo clearly has a great time animating the diabolical Captain Wingate, but Yasmine al Massri may be guilty of having the most fun of any actor in the film. The journalist Khuloud is among the liveliest figures in Palestine 36, with memorable exchanges of dialogue and comic scenes that are simply gestural — angrily lopping the flowers off her rose bushes or, at her typewriter, tipping a cigarette ash into Amir’s overturned tarboush.

There is a good deal of critical history in Palestine 36. If there is a shortcoming here, it’s not that it makes the film boring or “uncinematic,” but that audience members familiar with the broad strokes of Palestine’s early 20th-century history — and Perfidious Albion’s role in it — may find some of the film’s historical foreshadowing a bit obvious.