Speaking of Arab revolutions, Tugrul Mende reviews a new book from Stanford looking back at revolutionaries of Dhufar, south Oman.

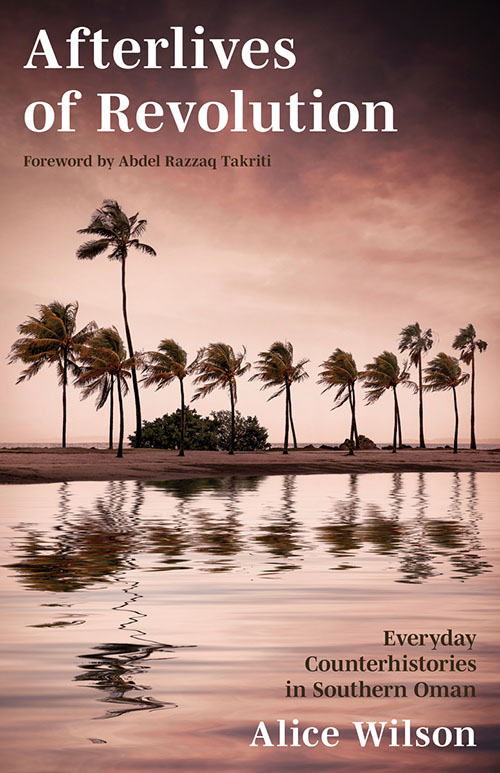

Afterlives of Revolution: Everyday Counterhistories in Southern Oman, by Alice Wilson

Stanford University Press 2023

ISBN 9781503634572

When Alice Wilson, a social anthropologist, went to the Sultanate of Oman in 2015, she had already been researching revolutionary social change for a decade. Several revolutions had happened in the region since 2011. As the political dynamics to which they gave birth increasingly met with backlash, it was more important than ever to understand how earlier revolutions, such as that of Dhufar (often rendered “Dhofar”), a southern region of Oman, evolved, and how revolutionaries who did not achieve the liberation for which they had struggled continued to live under the authoritarian state that they had once contested. The ongoing significance of revolutionary experiences in such contexts is what Wilson calls the “afterlives” of revolution.

The afterlives of revolution require not just reconsideration, from the perspective of what survives of revolution, of the putative endings of revolution and counterinsurgency. They also demand reevaluation of revolutionary contexts and times of revolution-in-progress.

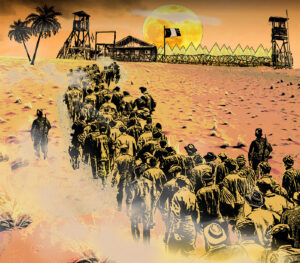

In a sense, the history of the Dhufar Revolution (1965-1976) is not yet over, and understanding it helps us gain insight into political and social developments that happened in the years after the revolution was crushed militarily. These developments still echo in today’s Oman — despite official government denial. While the revolutionary process was at its most intense in the 1960s and ’70s, the revolution lived on in different ways after its military defeat in 1975-’76.

In 2011, demonstrations broke out in Salalah, the capital of Dhufar governorate. Protesters demanded democratic reform and an end to corruption, and warned the government that it should not forget the events of the 1970s. In her introduction, Wilson writes: “Protests that began in Gulf monarchies in 2011 were recent episodes of longer histories of dissenting voices there that include the revolution in Dhufar.”

Not only does the Dhufar Revolution play an important role in Dhufari history, it has meaning for the present as well. Today, Dhufaris commemorate the revolution within their own informal social structures. These structures and how the revolution is looked at today form a good part of Afterlives of Revolution.

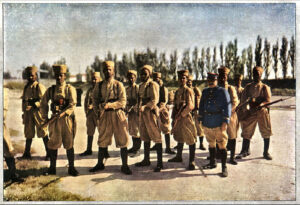

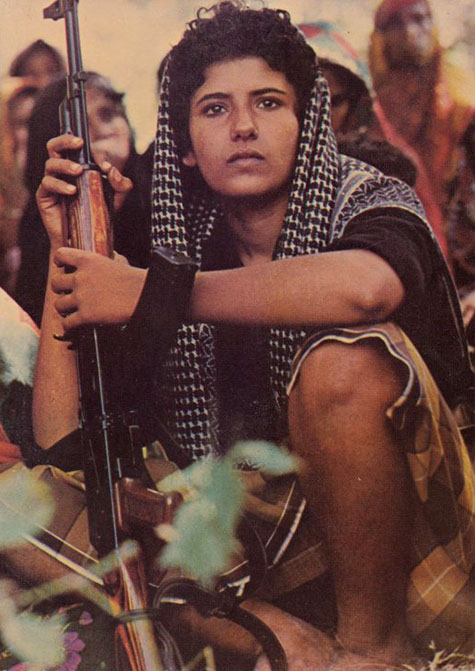

Wilson analyzes the revolution through the specific case of how Dhufaris challenged the status quo in the 1960s in their part of the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman, as the country was known until 1970. They established a movement called the Dhufar Liberation Front (DLF) in early June 1965, in a cave near Wadi Nahiz in central Dhufar. The aim of the movement was to end the rule of Oman’s sultan over Dhufar. Wilson discusses the DLF as well as its successor groups (after 1968), examining their inner and outer struggles. And, tracing its trajectory, Wilson shows how the revolution unfolded. It evolved into an armed struggle against the country’s military, which was backed by the UK (Oman was a British protectorate until 1970) and Iran, among other countries.

In an interview with TMR, Wilson explained that, today, “revolution is a very contested term in the Dhufari context.” While the Dhufaris see the events of the 1960s and 1970s as a revolution, the government prefers to call them a rebellion or an uprising. The government has effectively blacked out the war and in contexts outside everyday informal interactions, those who break this silence risk imprisonment. Yet as Wilson pointed out in the aforementioned interview, this episode isn’t a closed chapter in the history of Oman. People still engage with it and try to understand the ongoing significance of the revolutionary process. “The fact that protestors in Dhufar in 2011 chanted slogans referencing the 1970s,” Wilson points out, “suggests […] how appetites for alternative, progressive politics and social relations resurface over time.”

Dhufaris who lived through revolutionary governance and counterinsurgency violence have a distinctive experience of both, as well as their afterlives. But with revolutionaries having aspired to liberation for Oman and the Arabian Gulf, their history remains significant, and much debated, across Oman and beyond.

The ideologies that were the foundation of the DLF and its successors spanned Arab nationalism, leftism, and eventually both national liberation and Marxist-inspired social transformation. The author addresses the DLF’s ideological shifts over time. The people who were part of the Dhufari revolution are of various types and cannot be shoehorned into one category. They came from different classes of Dhufari society. “They were a mixed group,” Wilson said in the interview. The revolution attracted activists from other regions of Oman as well as neighboring countries, making the movement cosmopolitan.

One chapter in the book examines how counterinsurgency violence and rentierism transformed Dhufar. This transformation was part of the counterinsurgency movement that evolved during the revolution. At the same time, the interviewees in the book lived under “the authoritarian rule of the government that, with British backing, had waged the counterinsurgency,” as Wilson writes. The counterinsurgency was an ever-evolving issue for the DLF (often referred to collectively by Dhufaris as “The Front”). Counterinsurgency violence had “deadly consequences not just for Front fighters,” Wilson writes, “but also for Dhufari civilians.”

Interestingly, Wilson examines how kinship worked within the revolutionary setting and how it created new kinds of social relations. She writes that, during the revolution, “kinship celebrations for all Dhufaris were disrupted.” Finances were restricted to survival, and celebrating a wedding with a feast, for example, was unimaginable. Blockades separated relatives, and landmines and other hazards made it impossible for people to travel. In postwar Dhufar, kinship was a way to return to a situation of normality.

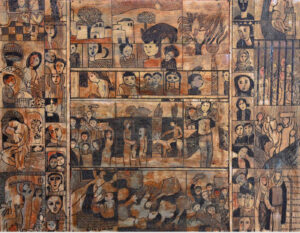

Dhufaris named children born during or after the war after revolutionary figures, and forged marriages in postwar generations along lines of revolutionary connection. This created social networks with shared memories and experiences. Nevertheless, as Wilson points out in the book, “[i]n revolutionary Dhufar too, kinship practices that reproduced social stratification sometimes persisted. Dhufari revolutionaries’ experiences reflect multiple intersections of kinship and social reproduction.” Wilson shows that for conservative Dhufaris, kinship enabled a welcome return of the social hierarchies that the revolution had earlier questioned. But for members of former Front families, kinship and wedding celebrations presented an opportunity to reassert revolutionary social values.

Everyday interactions are important for creating revolutionary afterlives. “The Sultanate not only forbade the formation of a political party or veterans’ association,” writes Wilson, “but also omitted mention of the revolution (and other episodes of dissent) from official historiography and routinely banned the sale of books on such topics. Amid such constraints, mundane everyday interactions that blended with ‘normality’ provided opportunities for creating revolutionary afterlives.” Wilson looks at these everyday interactions; they are informal and casual social encounters that take place among people who frequently meet in homes, workplaces, leisure venues, and public spaces.

Commemoration of the revolution is a major aspect of this book. The author traces the shift from the Front’s formal, official commemoration to the former revolutionaries’ informal, unofficial commemoration in later years. The author shows how former revolutionaries deal with the memory of the revolution in creative and unexpected ways. “Memory work about the revolution through fiction is long-standing and flourishing,” writes Wilson. Omani writer Ahmed al-Zubaidi (1945-2018) reflected on the revolution in a trilogy published in Beirut between 2008 and 2013. Omani novelist Bushra Khalfan revisited the Dhufar Revolution in her novel Al-Bagh, which was published in 2018. Beyond Oman, the Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim wrote Wardah, which deals with the Dhufar Revolution and was published in 2000.

All in all, Afterlives of Revolution is an important addition to our understanding of revolutions and their outcomes. There is much insight here into Dhufar — its history, politics, and social developments, in addition to the revolution itself. For academics, it is a highly recommended study in order to understand how the Dhufar Revolution influenced today’s Oman. For non-specialists, it is an interesting read because one learns much about the history of Dhufar and Oman, and because the author writes in a way that makes complex connections easily understood.