<

<

The unfinished Arab revolutions deserve our support.

<pdata-rte-preserve-empty=”true” >

Melissa Chemam

As world media began to follow the early days of the misnamed “Arab Spring” in January and February 2011, I found myself in Uganda, covering that country’s presidential election for the BBC, where the opposition candidate, Kizza Besigye, had no chance to defeat the incumbent president, Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986. I had studied journalism in Paris and one of my best friends there was from Tunisia. I immediately thought of her: she had grown up under Ben Ali but had always hoped she would see change in her country during her lifetime. She was then based in Cairo, and soon had to deal with two revolutions.

“This is above all a moment of new possibilities in the Arab world, and indeed in the entire Middle East,” Rashid Khalidi, the Edward Said professor of Arab Studies at Columbia University, wrote in Foreign Policy on February 24, 2011. “We have not witnessed such a turning point for a very long time,” he added. “Suddenly, once insuperable obstacles seem surmountable. Despotic regimes that have been entrenched across the Arab world for two full generations are suddenly vulnerable. Two of the most formidable among them — in Tunis and Cairo — have crumbled before our eyes in a matter of a few weeks.”

I came back from Kampala, feeling thrilled for them. Having grown up in France in a town led by a communist city council, I had always thought of revolution as a positive, radical and necessary source of change. In primary school, our teacher organized a play for us to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the 1789 French Revolution. My own parents and grandparents had also participated in their own revolution with the liberation of Algeria, but at the time—especially in France— this was a complete taboo. No one ever mentioned Algerians as revolutionaries, in public or even in private, yet in our house that’s what we were. Later on, when I studied history and politics more in depth, I met quite a few French people and even Arabs who despised revolutions, seeing them as form of violence coming from “the people,” meaning the unimportant lower classes. What they valued was order and hierarchy. However, I learned over the years that their reaction was a symptom of allergy to change, based on fear, and that no revolution was ever completed in one day.

It didn’t take long for skeptical voices to carp at the Arab Spring. Can Tunisia and Egypt really succeed in their popular revolutions? Will Libya and Yemen ever shake off their despots…with pundits implying that democracy in the Arab would always be an oxymoron.

Back from Africa, in 2013 I joined the newsroom of the international radio in Paris, RFI, in the African section. As the only North African in the team, I often had a chance to cover Tunisian, Algerian and Libyan issues. North Africa had always had this weird place in foreign news, in the UK as well as in France: it’s not completely Africa, but it isn’t the Middle East either… I noticed that many journalists often walked on eggshells when they talked about the region. But by 2013/2014 the general sentiment was that the revolutions had failed… Tunisia had an Islamist government (Ennahda won a plurality of votes in the October 2011 Constituent Assembly election). Egypt was a military dictatorship again. And Libya was in limbo.

But whenever the subject of the Arab revolutions arose, I wondered aloud and still wonder why no one ever compares them with at least the French Revolution—to be more historical, we should say the French revolutions. Victor Hugo, one of France’s literary greats, was born in 1802 into a bourgeois family but later became a true republican. Thirteen years after the French Revolution of 1789, he was forced into exile, however, for decades. He wrote Les Misérables, published in 1862, in exile. Because after “The Revolution”, France had two brutal empires—under Napoleon and Napoleon III—and as many royal “Restaurations” that only brought wars, more inequality and social conservatism. Had the French Revolution failed?

Well, in 1830, Paris had a second revolution after the collapse of Napoleon’s egotistic desire to dominate the whole of Europe… But the three days of the July 1830 Revolution soon led to the return of a French king: Louis-Philippe Ier. Then in 1848, France was swept away by a vaster movement of revolutions that shook the whole of Europe, known as the “Springtime of the Peoples” or the “Spring of Nations”. Italy and Germany didn’t exist back then, but were comprised of a cluster of sovereign provinces speaking dialects of Italian or German. It was a high time in European history. The same year, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who had fled Germany, published their Communist Manifesto. How did this revolution end? Well, in France it concluded with the election of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in 1851, who soon declared himself… an Emperor. In the rest of Europe, in oppressive, conservative regimes mostly, and Marx had to leave France and Belgium for England.

All these revolutionary events led to violence and to very conservative regimes, also kick-starting imperial and colonial rivalry between the European powers over their control of half of Africa and Asia. But it doesn’t mean they had failed; they were part of a longer process.

“If revolution is a regime change involving collective physical force, then the key dates are 1789, 1830 and 1848,” observed Peter Jones, a professor of French history at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. In the end, France had at least three major revolutions, and arguably a fourth one—La Commune de Paris in the spring of 1871—before it had a stable regime, the Third Republic. Yet even this regime didn’t lead France to become entirely democratic, not until at least the turn of the 20th century and not until the country had been torn apart by the Dreyfus Affair from 1894 until 1906. Victor Hugo didn’t live to see the Third Republic, for he died in 1885, while the French regime was still very conservative. Then of course, even after 1910, women still could not vote (they couldn’t until 1944!), and the largest part of the population of colonized Algeria—declared French territory—was deprived of fair parliamentary representation.

The transition to a republic didn’t prevent Vichy or Dien Bien Phu. The French Third Republic ended up in the painful and disastrous Second World War, and the humiliating collaboration period. Then the Fourth Republic, established after WWII, died out in a civil war, over the horrifying settler colonialism in Algeria, in 1958. This gave birth to a Republic of “emergency” or what François Mitterrand often called “la République du coup d’Etat permanent,” the Fifth Republic and current French regime.

<

<

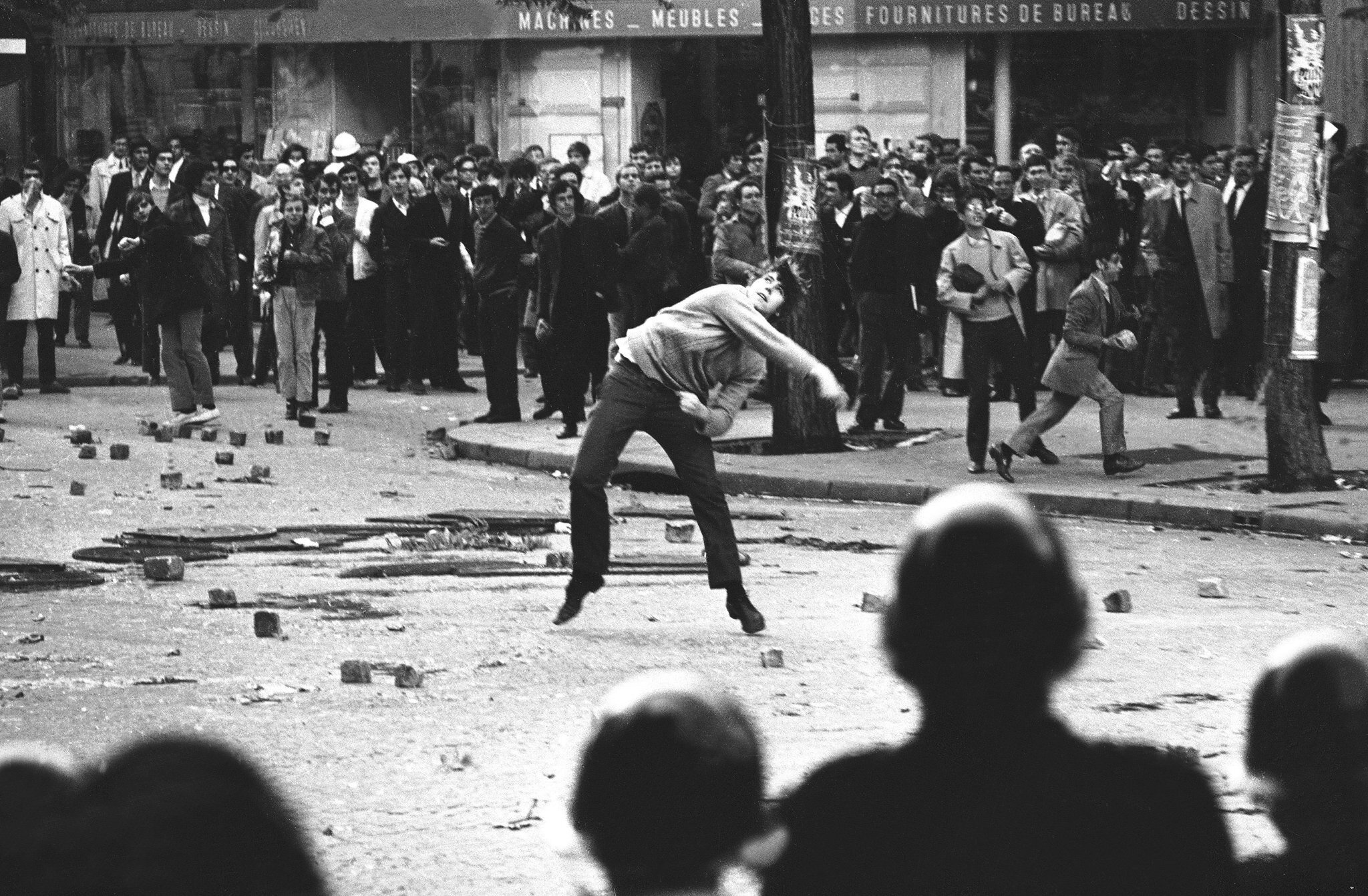

Paris 1968.

Even then, revolutions weren’t over, for a socialist and labor/student-led uprising broke out in Paris in 1968 and soon engulfed the country, bringing the French economy at one point to a grinding halt. May ‘68 marked the world much in the way the 1789 Revolution had.

We could also draw parallels with American history.

One revolution that is too often forgotten is probably the most important of all in terms of balance between the West and the rest of the world: From August 21, 1791 to January 1st, 1804, the Haitian Revolution made European domination over the Caribbean a reversible phenomenon. One might say that the Haitian revolution isn’t over; certainly Toussaint Louverture has become a hero inspiring Africans and African Americans to this day.

The American Revolution, which took place between 1765 and 1783, only concerned colonial North America, meaning 13 states and their white settlers, in a fight to free themselves from their British oppressor. But all the other human beings living on North American soil at the time were simply ignored and denied citizenship, first and foremost the Native population, the First Nations, as well as the displaced African slaves. Up until the mid-20th century, American democracy remained a nuanced reality: despite the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution passed in the 1860s—all intended to enfranchise Black Americans—most could not vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

The Egyptian-American journalist Mona Eltahawy, author of The 7 Necessary Sins for Women and Girls (2019), actually referred to the civil rights movement as a revolution on Twitter on January 25, 2021, while commenting on the Arab Spring. She wrote that: “A revolution does not happen overnight. And because, as Audre Lorde insisted, ‘Revolution is not a one-time event.’ I will not write its obituary.”

Ten years after 1789, France was about to have a new Emperor and to plunge Europe into war. Ten years after 1848, it was at the height of the Second Empire, and its best author was writing in exile. So, ten years after the Arab Spring began, I would argue that we should give Arab revolutions some time.

<