Mosaic mural photographed by Walid Mahfoudh (Flickr/Walid Mahfoudh) <

<

“Throughout history many nations have suffered a physical defeat, but that has never marked the end of a nation. But when a nation has become the victim of a psychological defeat, then that marks the end of a nation.” Ibn Khaldun, Al Muqaddimah.

Farah Abdessamad

I remember our days together jasmine, when you were little (and I barely taller), not even reaching the window frame. You had tried climbing along the blue window bars and we helped you with support stakes. I had heard the adults whisper his name in our own living room and as they shivered, I shivered, too. Later I joined them and lowered my voice. We were terrified of invoking a ghost, or worse, a divinity. We were careful because there had been reprisals. People disappeared and families waited, sometimes forever. Now he’s gone. Yes, the raïs finally left and it’s been a decade.

I’d love to tell you what I’ve seen since those days—you stayed, I left. I freeze instead at the fragile equidistance between two points, Hope and Disenchantment, a function of one another, trying to measure these two looming towers of impossible heights. The latter pulls me, and I linger just a bit longer in this threshold, not to let the things that matter be forgotten.

Changes started ten years ago, with a winter depleted from the scent of orange blossom that lingers in the air. In winter, the sky would turn grey during months without tourists, without the returning emigrants with their hard currency enveloped in nostalgic fog and filial duties. The rain brings sadness and we usually shiver inside our homes which have not really been built for the cold days. I imagined then that you also longed for a harassing sun and the giggles of children running and splashing at each other, playing in our sea.

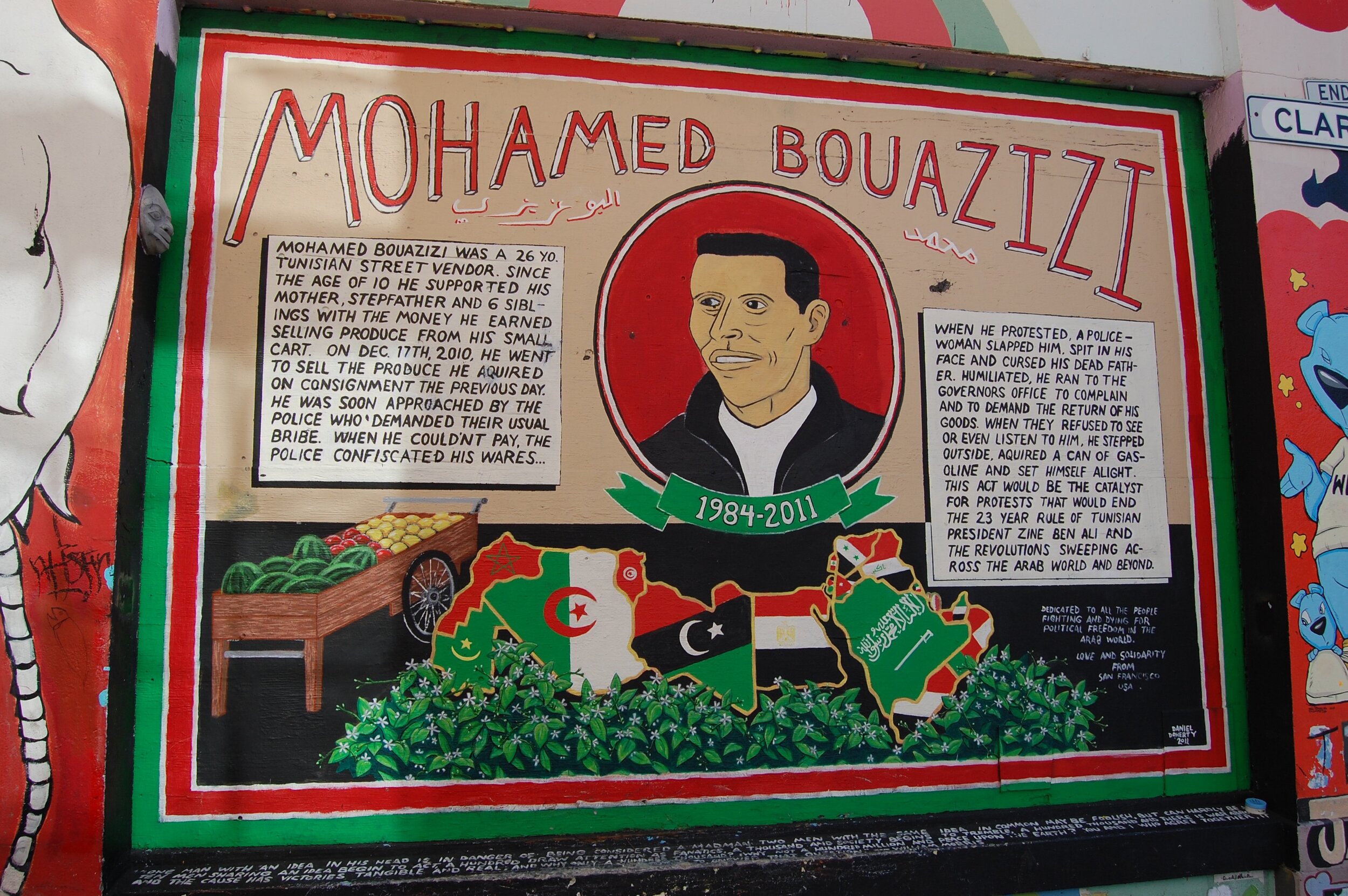

It started a long time ago, maybe. You know that this land had sacrificed its most precious in old, yesteryear times, to calm the currents and appease the gods. Tunis wasn’t yet Tunis, and Tunisia was the name of a continent—Africa. We don’t like to remember it today and we swear that the site by Salambo is part of a larger cemetery, that the children died of natural causes. The remnants of their steles face towards the rising, blazing sun. Fire, this essential, boundless, sacred energy—a necessary heat to stay warm, an excess which kills you—was the only element able to connect the mortal with the immortal, the profane and the sacred, in the hope of healing and rebirth. And the street seller set himself on fire and died, leaving juicy, fragrant citrus fruits and a few vegetables in his cart, in a propitiatory gesture of primordial truth—older than the Carthaginian infants had been when likewise sacrificed.

Street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation sparked the Tunisian revolution (Flickr/Far Out Flora)

<

<

On the docile flames from our gas stoves we grill the skin of green and red chilies. We then mash them in a salad. It stings the tongue, and it’s tasty. Ten years ago, I wrote strange words to update friends on a virtual platform who until then, didn’t know who you were, beyond the collected details of your kingdom, order, family, and variety. I wrote about government-backed snipers shaking our lives, about looting, curfew and reports of dead people whose blood irrigated your vines.

This shoreline hasn’t always been mine. My ancestors left their native Arabian desert many centuries ago. They fled. Their belief was initially different. They worshipped the old idols and suddenly were told of a new god, The One with ninety-nine names. They weren’t sure about these changes at first and my tribe rebelled repeatedly, taking up arms along the losing sides. They went east first, to modern-day Syria, Iraq and Bahrein, chasing after the hypnotic clarity of sunrise. They were expelled later (thanks to a propensity for dubious alliances) and turned west. First, to Egypt where they found a respite before a famine hit. Then they marched towards the evening of the world, reaching the African pink skies of the proud Romans, where a man named Hannibal was once born.

There were more wars. We settled south mingling between hot desert springs, with Jews and Imazighen, whose water we drank, and whose land we now occupied.

I didn’t realize how many Tunisians there were. I knew, but I didn’t understand what a multitude meant until they all came out in the streets on my TV screen, compact like a nationwide ant colony. I watched between two power outages, from my Beirut apartment, proud and anxious. They walked under the golden-tipped clock tower next to the capital city of a fallen empire. Are we too late, I asked myself. Time devours his children; the hands of the clock keep moving and their motion was a call to action. Ten years, that’s 87,600 hours.

It’s happening, I told everyone. It’s happening! We were the children of Harun Al-Rasheed’s exuberant tales, the children of his Ali Baba and we would retake stolen treasures from the thieves. I wanted to see you again and measure how tall you’d become. I imagined a future.

I didn’t hop on a plane to meet you. Our fire was contagious and set the region ablaze in a collective pyre for which we weren’t quite prepared. After the initial exhilaration, something went wrong.

Many winters later, though some would say rather quickly, the fruits of our gardens turned sour. Clouds hung lower. The sea wept. And at some point, you—gift from all gifts—even stopped blooming in the evenings. Elders started to regret the man they used to gossip about. They said life was too expensive, that garbage supplanted the wave of protesters and piled up in a horrid stench. They wanted clean streets, the luxury to be bored again, to buy food without depleting their dwindling pensions, to be sick without worrying about medication we can’t find in the country.

Years passed. From bills, to baksheesh, deflagrating bangs followed by louder silences. A beach, a museum, rubbles and debris. A taciturn, black banner conquered new spaces. I gazed before at cheeks-painted faces and bodies hugging a scarlet flag. I mourn the dead people I see daily on my online feed. I don’t know them, and I can’t help but notice the appearance of tiny bones and heads on some of these photos. I try to decipher their blood stains like a grandmother reading destinies in coffee grounds. They feel close; they feel like family. The tourists have left and haven’t come back.

Our land is known for its finest olive oil. The best one is humble. It carries a residue at the bottom of plastic bottles we often exchange and reuse. And today, we have a new export commodity to collect extra revenues: the indiscriminate pulp of hopelessness from our young people’s flesh. One can dip a piece of warm bread in our congealed, cracked dreams. Many have learnt the ways men can die to satisfy virginal fantasies—while others simply fight to breathe.

In ten years, it seems to me that after the whip splash and intoxication of colorful, historical afternoons, we haven’t discovered how to love being alive, guiltless and shameless, to climb to the tip of a colossus and survey the vastitude of our own possibilities. One leg in Tangiers, one leg in Antioch, a valley of abundance underneath—why haven’t we?

It wasn’t supposed to perish so fast and so decadently. We were to celebrate the force of life and pleasure and a carnal, whole, Dionysian desire. At night, I wonder if these were tragic games we were never supposed to win. Maybe we’re the guests to a celestial banquet and we’re the feast.

My memories, those that are mine and the ones I have adopted as orphaned realities, haunt me. They seek to implant and propagate; they want to control me. I try to hush them but I fail. I catch echoes that appeal for a sense of urgency and scream after news of a wreck. I hear voices, conversations, slogans—dignity! The voices are searching. They’re asking for directions. I point them to the clock tower which only melts away.

During a period when we kept time according to the sun’s shadow, a brutal murder is said to have taken place in Ancient Egypt between two brothers. Osiris lost his kingship to Set, who dismembered him. His widow Isis looked out for him and cried inconsolably. Her tears filled the Nile, spilling in the sea which had collected Osiris’s dispersed pieces. She sailed off determined to find his missing remains. She succeeded, and a child—Horus—was posthumously conceived. Once adult, Horus avenged his father and defeated the power of his greedy uncle. Osiris lived on in the underworld while his son took his former seat governing Egypt. Order was restored; chaos was vanquished.

More tears and maritime wanderings have coalesced into our frothy sea. The name of Isis resonates differently to our ears, less of a savior than a threat. The goddess hasn’t appeared to rescue a hungry chorus of misery from the crammed, capsizing and deflating boats.

What’s left of my tribe after ten centuries is leaving again. A new exodus has begun and our common language is a language reaping a harvest of destruction. West? North? East or South again, back to a place where the sand can encrust our loose leather sandals as we wonder how to grow anything on barren fields? And we would succumb to an unquenchable thirst for things we can’t hold and slither away.

I speak of we and this cyclical “we” once swollen and gushing keeps shrinking like everything else. Delusional sensibility entraps me in the aftertime of a Spring meanwhile we’re locked in stasis. Together, we, two or infinity, ten years or ten centuries, I no longer know and use the words interchangeably.

I’m a speck of soot, a nigella seed stuck between someone else’s teeth. I represent nothing, no one, and my own fleeting image escapes me, too. I wish we had composed an expanded materia medica that would have collected remedies for our ailments—if you are sad, take this; if you need more rights, drink that; and if you want a future, one that shines and smiles, find this herb in that location, boil it until tender and as thick as a paste, let it cool, apply it all over your face for ten consecutive years. You’ll see a difference then.

While I still hope for a bigger we, one which brushes against the borders of epic rivers, the sea and the desert, the image of a sky comes closer in my dreams. There, I see a shape twirling sometimes, approaching and vanishing. It doesn’t scare me and no, I don’t think it’s the angel of death visiting prematurely. When its golden neck shimmers under a midnight sun and my eyes meet its purple robe, I recognize the mighty animal. I welcome it with pure joy. There’s a flaming halo enveloping its body, including along its saffron-colored feathers. It lives beyond 500 man-years—even one thousand according to some—and its nest is made from cinnamon and frankincense. It tickles my nose. It’s

the comforting sight of another Semitic creature.

Phoenix comes from the same root word as Phoenicia, and ancient writers agree on the bird’s provenance: Arabia. Its death is either flamboyant, consumed by ostentatious fire, or as slow as human decay. From its ashes, it rises again. A new cycle begins from this rebirth, just as the sun returns every day to break the chains of our nights. I wake up before I can touch the burning feathers. I watch the bird ascend into the ether when it merges with other beams and the love-fire spark of Venus.

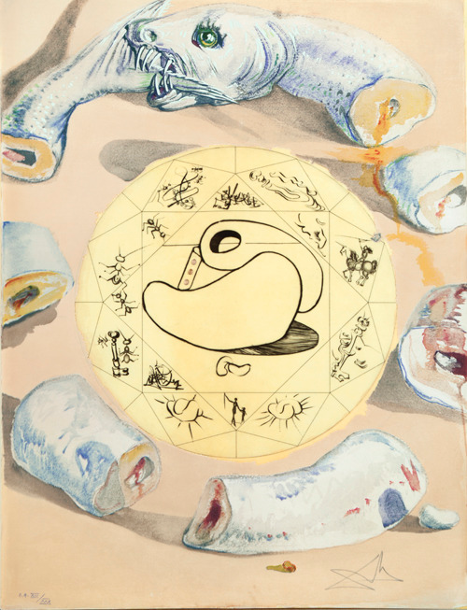

L’Ouroboros, Salvador Dalí <

<

“Despise not the ash, for it is the diadem of thy heart, and the ash of things that endure,” a 16th-century alchemy treatise, the Rosary of Philosophers, instructs. In its hey-days, alchemy pulled together elements, such as fire, water, air; qualities, hot, dry, cold, humid; and principles, such as volatility or stability, to study the workings and possibilities of transmutation. It embraced traditions from the fields of philosophy, chemistry, medicine and spirituality. Through distillations and purification procedures, an alchemist hoped to generate an elixir of perfection—gold, eternal life, a return to the divine. Conducting their careful experiments and tempering with substances, medieval alchemists from the Arab world challenged the impossible with an ambition to elevate the basic to noble, to combat degradation and control alteration. Yet no new life can arise before the death of the old one. The serpent eats its own tail to illustrate that “the one is all, and all is one” affirming it obeys a universal law which binds all of its living components together.

Enantiodromia is a fancy word to describe one thing running to an opposite, such as hope colliding with despair, hugging in a combustive, tight embrace. We shout but who listens anymore? We’ve been tossed aside. No one needs our beaches and handicraft and oil anymore. We’ve slipped out of history, in the periphery of larger stakes and bigger empires. Or rather, we joined history and history vomited us the same way the sea dejects its plastic content on our shores every day. After so much desolation we’re missing an immunity. Our pain seems to be the unintended anecdote to a palimpsest. Who holds the pen to our erasure?

Is it all about retrograding, or starting over, I wonder. Al Nadhim conserved a monumental body of knowledge in his medieval Kitāb al-Fihrist, passing a torch of scholarship and awakening from one civilization to another. There has to be more, more than a glitzy cage and more than live-streamed noise we leave behind for those not yet born. It’s tight in there, stuffy, and I know there’s a way out because there has to be one to reverse the harrowing dimness of this impasse.