Sarah Ben Hamadi

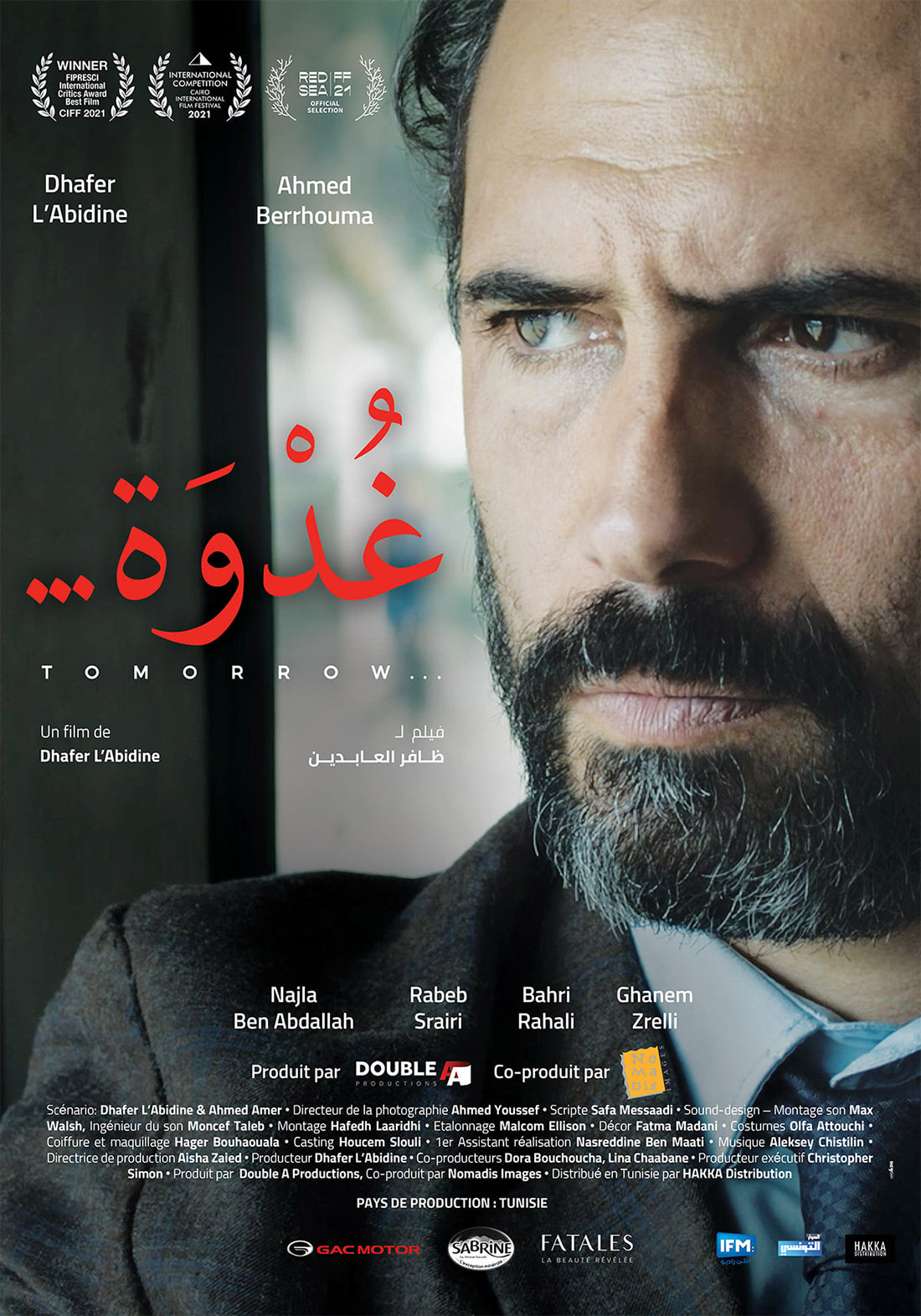

Ghodwa (Tomorrow in English and French versions), by Tunisian actor-director Dhafer L’Abidine, is a social drama that plunges us into the daily life of a human rights lawyer who, ten years after the Tunisian revolution, is still in search of social justice. Last winter, the film won the International Federation of Critics’ Award (Fipresci) at the 43rd annual Cairo International Film Festival.

L’Abidine not only stars and directs, but he is the film’s co-writer and co-producer, playing multiple roles in his first feature film behind the camera. “It is the realization of a dream,” he confided to the media.

We find ourselves in 2021. Habib, the main character, is a 40-year-old lawyer, traumatized by the abuses committed by the former regime under which he himself suffered. He clamors for “Truth, justice and then reconciliation.” This triptych haunts him, as he struggles, ten years after Tunisians rose up against the authoritarian regime of Ben Ali (1987-2011), to demand freedom and dignity.

Obsessed by this quest, frustrated by a system that has not changed despite the popular uprising, Habib, who still suffers psychological scars resulting from torture under the old regime, keeps repeating in his moments of delirium that “the revolution is coming,” as if he refuses to admit that it has already passed and that it has betrayed his hopes.

Disillusioned, wandering the streets of a disenchanted Tunis, where poverty persists, where police abuses continue, and where hope for a better life seems to have vanished, he refuses to accept that this reality is the outcome of a revolution that has nourished so many aspirations, and dashed so many dreams.

Habib’s relationship with his son Ahmed, central to the film, is endearing. Ahmed (played by Ahmed Berhouma), is very attached to his father, even as his health is deteriorating. As the film progresses, the roles are reversed and the son takes charge of his father. Ahmed does not understand his father’s attachment to this cause that reminds him of his demons, but he never judges him. He loves him as he is, and he is about to take up the torch and walk on the thread of hope.

“It’s a story that comes from the heart, it’s a Tunisian story, and it’s a story that I think is very important in relation to the Tunisians,” L’Abidine said in an interview with RTCI on the eve of the release of his film in theaters in Tunisia. And indeed, it is difficult to be insensitive Habib’s trauma, when we lived through the Tunisian revolution in 2011 and we had so much hope for a better tomorrow.

The languor of the shots may sometimes seem heavy, but it is a choice defended by the director. “This slowness is a marker of the staging, insofar as it is to make the viewer live the daily life of the main character with its share of trauma,” L’Abidine explained to the Anadolu news agency. This neo-realist directing technique has earned the film some criticism, although it has been well received in Tunisia, particularly for the message it carries, a “hard duty of future generations” according to the newspaper La Presse de Tunisie, which also notes “a very successful lead role, written by the actor for the actor.”

“Truth, justice and then reconciliation” Habib repeats throughout the film, a phrase that is reminiscent of the “Menich Msamah” (“I will not forgive”) campaign launched by a collective of young people, opposing the so-called “economic reconciliation” law in 2015, for whom “there is no reconciliation without justice.”

The film thus points to the inability of the country’s new leaders to implement a justice process. However, Tunisia has initiated a process of transitional justice through the creation of the “Truth and Dignity Commission” in December 2013, but it must be noted that the record of this body has been strongly disputed and contested, and that Tunisians retain a bitter taste, and continue to carry in them the feeling that the system has remained the same and that the expected justice has never been achieved.

One positive outcome of the Jasmine Revolution is that there is no censorship in Tunisian cinema today, and with this freedom of creation there has been an explosion of films and plays over the last decade. The main problem is finding film financing.

Still, at the end of the day, Habib’s condition reflects that of Tunisian society, frustrated to see that men have changed but that the system has remained, like the public prosecutor who no longer wants to hear about the old cases. But also like Tunisian society, Habib finds refuge with his neighbors, who support and comfort him, as is often the case in working-class neighborhoods in Tunisia.

With his first feature film as a director under his belt, the emblematic Tunisian actor signs a bitter declaration of love to his country, depicting an allegory of this Tunisian society that is disrupted, and sometimes derailed, but still has hope for a better tomorrow — Ghodwa.

I have just watched the film and I am very impressed by the story and the acting. The lawyer’s ordeal has been repeated in many Latin American countries where human rights were violated and the culprits have not been punished.