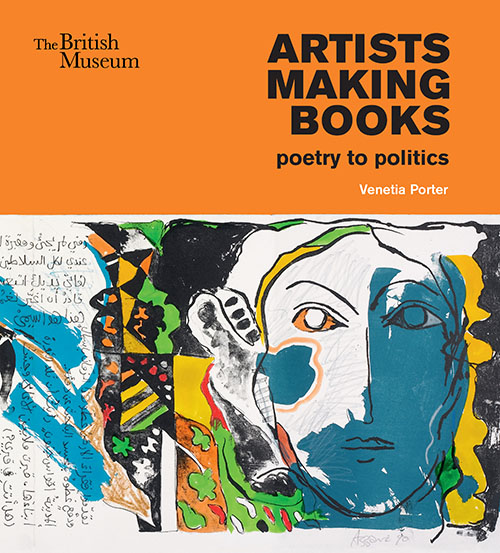

The unbridled creativity in artists’ books from the Middle East.

Artists Making Books: Poetry to Politics by Venetia Porter

British Museum Press 2023

ISBN 978-0714111971

Sophie Kazan Makhlouf

Artist books or artists’ books are used by artists to broach personal topics or stories, which include collages, photographs and illustrations. These books can be handcrafted collections of paper, sometimes sewn or gathered together in a sleeve or box, often made by the artist and this can add symbolism to the work. The term “artist book” can also loosely be given to ceramic or mixed media “pages” or collections, bound together or drawn together by lines, words or by other means. Not to be confused with the more haphazard sketchbook, artists’ books are gaining increasing interest on the global art market, both for their conceptual value, as well as for their significance as artistic expressions.

Artists’ books have been Venetia Porter’s passion for a number of years. The former Senior Curator for Islamic and Contemporary Middle East Art at the British Museum knows the department’s collection of books very well. She has also been responsible for the acquisition of many of the contemporary books in the collection. Her latest publication, Artists Making Books: Poetry to Politics is a rare treat because it offers a passionate and extremely well organized analysis of over 60 artists’ books from the museum’s collection.

Islamic and Indian artists, Porter tells us, have made books that pre-date by several centuries the more widely recognized French livre d’artiste of the 20th century. Nonetheless, the illustrated books of poetry and novels by French artists such as André Derain (1912) inspired English and American artists in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Jim Dine and Alan Munro Reynolds. These “Western” examples also acted as reference points for “Middle Eastern” (largely Arabic speaking and Iranian) artists, though Porter points out the multiple sources of inspiration and “convergence of traditions” absorbed by artists in the collection.

The book’s first chapter, A literary heritage, includes 14 artists’ books related to classical literary works. An early translation of Alf Layla wa Layla or One Thousand and One Nights, was made into English in the early 19th century by Edward Lane with Arab scholar Ibrahim al-Dusuqi, and into French in the mid-20th century by Algerian author Jamal Eddine Bencheikh. Drawing on the French translation, Tunisian artist Nja Mahdaoui presents a loose-leaf printed collection of pages, animated with “calligrams” of creative hurufiyya script resembling Arabic calligraphy. One type of artists’ books includes annotation or creative improvements on pre-existing printed work. Mahdaoui’s work fills and rises out of the margins and some of the book’s central folds. It is largely illegible and forms a tight patterning which blossoms or flows over the page.

Examples of an alternative form of calligraphy, nasta ‘liq is used by the artist Jila Peacock to write or draw poems by the Persian poet Khwaja Samsu d-Dīn Muḥammad Hafez Sirazi, more commonly known as Hafez. Peacock carefully crafts each poem into the shape of its subject, most often a fish or a bird. Returning to Lane’s 19th century translation of One Thousand and One Nights, contemporary writer and translator Yasmine Seale uses printed pages as a basis for her own painted, textured and mixed media visual poems, entitled Erasures. Her work blots out or outlines the conditions and limitations of the text’s orientalist translation and historiography.

A highlight of this first chapter is Iranian artist Parvis Tanavoli’s cutting of his characteristic heech (nothing) shape into the inside of a handmade hemp book bound with suede spine. This form of shape-making recalls the way in which secret objects are illicitly concealed in spy movies or novels and the word therefore becomes both ironic and playful.

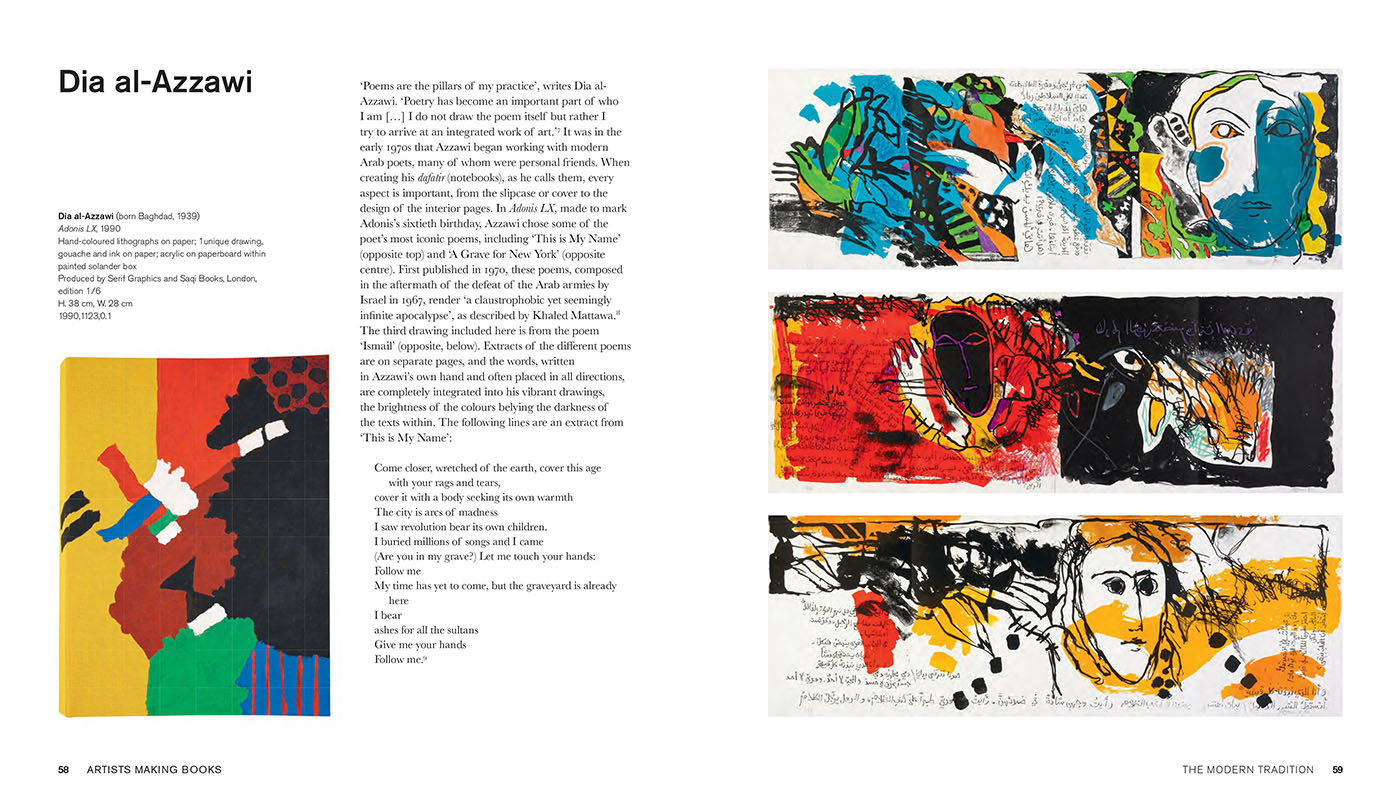

Artist Ali Akbar Sadeghi interweaves the epic Shahnameh (The Book of Kings) with poetry quotations by the 14th century Persian mystical poet, Hafez and the iconography of Iranian miniatures to create his own version of the Asheqnameh (Book of Lovers), 2016. Many artists in the collection appear to have been inspired by mystical Sufism and the poetry of Rumi and the late 12th century allegorical Persian poet’s Farid al-Din Attar’s Conference of the Birds. Bahman Mohassess illustrates reprints of an allegorical novel based on folktales by 20th century intellectual Al-e Ahmad, with humorous linocut prints in a limited edition run of Nun wa al-Qalam (By the Pen), 1961. Shakir Hassan Al Said uses the casual Daftar (notebook) format, popularized by the Iraqi contemporary artist Dia Al-Azzawi in the 1990s in response to UN sanctions imposed on Iraq.

Porter uses Azzawi’s wonderfully evocative description of the daftar as being “like a closed room with windows. Once opened, the light leaks out to reveal the worlds … the unlimited freedom to use any material.” These notebooks are inspiring examples of artists physically manipulating the pages of the books to make them reflect their personal creative journeys and artistic expressions.

It is interesting to see the different artists’ interaction with the text and the materiality of the books themselves. Though some books maintain their traditional two-dimensional forms, artists have created boxes, slipcases and holders to conceal or protect them, while also transforming them into an object or artifact.

The second chapter focuses upon books inspired by contemporary literature and poetry. Here the work of many artists feature the work of two important modern poets and authors, Palestinian Mahmoud Darwish (1941–2008) or Syrian Ali Ahmad Said (a.k.a. Adonis) (b. 1930) whose own mixed-media collages from the early 2000s also feature in the British Museum’s collection and exhibition. These poets expressed a contemporary feeling that appealed to artists such as Dia al-Azzawi, Shafic Abboud, Mohammad Omar Khalil, Himat Mohammad Ali, Kamal Boullata, Ziad Dalloul, Rafa Nasrir, Abdallah Benanteur, Rachid Koraïchi, and Issam Kourbaj.

Kourbaj created a book that appears to be shattered into 24-secondhand book fragments containing sections of Darwish’s poem, “The Damascene Collar of the Dove,” as a commentary on the Syrian civil war. Works by artist-poets such as Shideh Tami and Etel Adnan, also appear in this section. Adnan’s now well-known and recognizable folded concertina books have been displayed in various public and commercial galleries including the Tate and the Serpentine Galleries in London, Lelong & Co. and the Whitney Museum in New York, as well as Adnan’s Sfeir Semler Gallery in Beirut. Adnan’s Nahar Mubarak (Blessed Day), 1990 is a painted poem which evokes the careful creation of painted scrolls in Japanese and Chinese artistic tradition. Using bright colors, decorative lines and symbols Adnan animates the pages of the book until they appeal to Arab and non-Arab readers alike, as works of art in themselves.

Other artists such as Assadour, Mehdi Qotbi, Laila Muraywid, Ahmed Morsi, Mohammad Omar Khalil, Lassaâd Métoui and Farid Belkahia have created their own collaborations with writers and poets to create original artworks, prints and limited print editions which illustrate or express their own response to the contemporary written word.

An unusual example of an artist working with contemporary literary work is Ala Ebtekar’s exploration of the moon’s cycles using cyanotype on found book pages with reference to the magical and mystical subjects expressed by writers such as Shihab al-Din al-Suhrawardi, Farid al-Din Attar and Omar Khayyam. These books are stacked in various shades of deep blue. They are dotted with pinpricks of light that resemble the night sky.

Books associated with historical and world events in the 20th and 21st centuries; the war in Iraq in 2003, the collapse of colonialism and the Arab Spring, form the focus of the third chapter, Histories of the Present. We return to the dafatir (notebooks) as a repository for personal thoughts and physical intervention. Artists Kareem Risan, Mohammed Al Shammarey and Maysaloun Faraj’s “book objects” reflect the devastation of the Persian Gulf Wars. They focus physically on the book covers themselves but include some writing or printing.

Rachid Koraïchi has combined pages of lithographs with calligraphic text by Algerian novelist, Abdelkader Boumala and the poet Mohammed Dib — who wrote most often in French. By creating this unbound book of verses in Arabic, shapes and symbols, protected by a rectangular box resembling a gun case, the artist is reclaiming not only the author’s identity as an Arab but also Algeria’s troubling history at the hands of the French.

Khalil Rabah’s Dictionary Work, 1997 is a large book, a dictionary, whose open pages are pierced with sharp nails. The twisted, silver-colored nails create a powerful image. They cover the open surface of the tome, leaving only a small portion of text uncovered — the definition of the antiquated term, Philistine. This word is used in the Bible to refer to the ancient people of Palestine who were often in conflict with the Israelites and Canaanite people of the Southern Levantine region. They were regarded negatively and are defined here as being boorish and “hostile or indifferent to culture.” The imagery of nails dug into the words around the reference suggest struggle, agony, antagonism and also the continued problematics of this region.

Books as receptacles for memory and artifacts of the past are evoked by artists Ali Cherri and Khaled Malas/Sigil Collective. The latter considers the impact of electricity on Syria, as both an object of torture and as a means of resistance. Muhammad Zeeshan examines representation, depiction and the importance of identity in his works on handmade wasli paper. Wasli paper was specifically made for painting and Zeeshan proves its worth by painting lines upon it that are so fine and winding, that the viewer could easily mistake them for embroidery or sewing.

The final chapter, Place and Displacement, features artworks in a variety of media that evoke the biographical importance of the written word, documentation and illustration. Expressively painted paper and cloth books are filled with tales of family, of exile, memories and passion.

In others, artists such as Ipek Duben, Diana Matar and Akram Zaatari have used printed images and photographs as a way of commemorating, witnessing or “proving” the past. Duben’s work uses newspaper images of refugees and displaced people printed onto delicate synthetic silk, which he then embroidered with dates and finer details. These details show his own personal connection or knowledge of the people in question and this is also a touching act of care or humanization of media images. Diana Matar’s quest for her father-in-law who went missing under Muammar Qaddafi’s rule has resulted in her book Evidence, 2014 about the violence of the regime.

Akram Zaatari’s Book of All Collections, 2019 is an index of the Arab Image Foundation, which the artist founded in 1997. It is an archive for collections of photographs and has formed the basis for much of Zaatari’s work. This book includes many personal photographs prized by the thousands of people fleeing the Lebanese Civil War, who took refuge in countries around the world. These images document the people of the diaspora and Zaatari invites us to consider the images chosen and those left behind. He also has several archival collections of photographs from studio photographers. These were either donated or acquired by him, the foundation or were found in the destroyed buildings. These forgotten or unclaimed images are part of “Annotated History” that Zaatari brings together in this work and books.

The Dubai-based collaboration of artists, Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh, Hesam Rahmanian have joined forces with the poet Vahid Devar to create a new entity, RRHV, for Philip’s Atlas of the World. This is a Royal Geographical Society Atlas. It has been filled with several different forms of “interventions” on its pages — from poetry by Davar, written in Persian and translated into English, to pasted images by the artists that comment on the refugee crises and gradual movement of populations, in, on, or around atlas maps. The result is a disputed document laden with ideas, annotations and additions. These reflect the jumbled situation of global politics and possibly also the artists’ feelings of nationality.

Artists Making Books is not a simple catalogue of the British Museum exhibition which shares its name. It is more of a reference guide or lens through which the reader can consider the range of books created by artists and appreciate their variety and power. Porter’s research, her choice of imagery and description use works by artists from the “Middle East” to broach the subject of artists’ books or artist books as a broader genre.

This introduction, through its specifically Eastern lens, opens up a world of creativity and kunstwollen. This term has been translated as a “will to form” and it was used by the 19th century Austrian art theorist Alois Riegl to express the process of art-making from inspiration to creation. That is the great value of these artists’ books. They are arguably more valuable than a traditional work of art, or single act of creativity, seen in isolation.

These books, whether illustrations of selected words or stories by other authors or whether they are illustrating stories or single words by the artists themselves, express through color, form, and rendering the creators own inspiration and context. Porter has transmitted her own sense of admiration and wonder through Artists Making Books, which is essential for anyone interested in art from the SWANA region. The books reveal the creativity of artists in their most raw and honest form.

Artists Making Books: Poetry to Politics in also the title of an exhibition currently showing in the Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World at the British Museum, until February 18, 2024.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)