Soheila Sokhanvari’s Rebel Rebel is on at London’s Barbican Art Gallery and the Curve through the 26th of February, 2023.

Malu Halasa

A towering mirrored “Monolith” stands at the entrance to Soheila Sokhanvari’s exhibition Rebel Rebel in the Curve Gallery, in London’s Barbican. The over 13-foot high sculpture, made from wood, metal, Perspex mirrors and glitter, casts brilliance and shadow on the hand-painted Islamic geometric murals covering the floors and walls of the gallery, showing 28 portraits of feminist icons from pre-revolutionary Iran. At the base of the “Monolith,” sharp, sparkling shadows blur and fade into chaotic amorphous patterns, an apt allegory for the lives of important female Persian cultural figures from before Iran’s Islamic Revolution.

Prior to 1979, poets, actresses, academics, pop stars, film directors and ballerinas — women from all walks of life and professions — fuelled the rich tapestry of Persian arts, culture, language and literature. There were those whose work didn’t fully stop after Ayatollah Khomeini took power 43 years ago. Some were arrested and sent to Evin Prison. After they were forced to write letters, which repudiated their former lives — sadly the experience of many of the actresses — they continued some semblance of their careers. Others left public life entirely, descended into addiction; or died in obscurity. A small minority fled the country and continued working abroad, never to return.

The eyes of Iran’s tragic poet Forugh Forrokhzad (1934–1967) and her cat stare, searching and accusatory, peer out of Sokhanvari’s portrait. Forrokhzad was the nation’s best-known poet. In publishing under her own name what was considered sexually frank poetry for its day, her son was taken away from her after her divorce. She died tragically young in a car crash at the age of 32. Her painting is named “Let Us Believe in the Beginning of the Cold Season,” after her posthumous collection of late poems. Each of the other 27 portraits has been given a title inspired by the creative lives of its subjects.

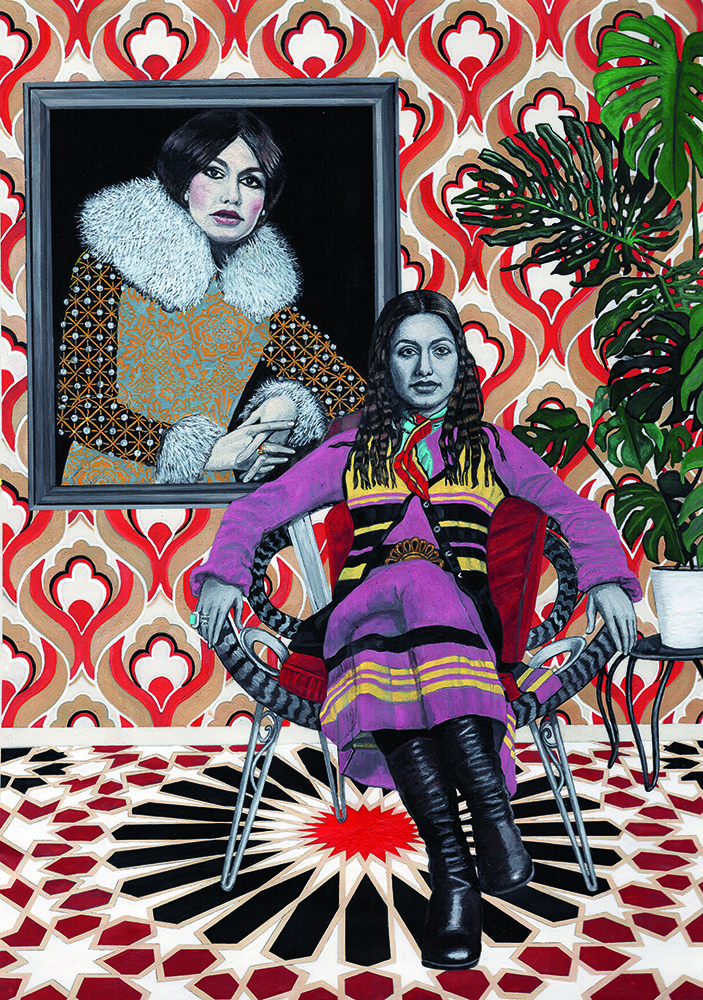

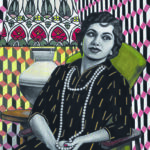

“The Love Addict” is Faegheh Atashin (b. 1950), better known as the famous Iranian singer Googoosh, renowned for her emotional ballads of heartache and loss. In 1979, Googoosh was traveling outside of Iran. She returned to the country, and like all women performers, was banned from singing until the so-called “reformist” presidency of Mohammad Khatami in 1997. She left the country three years later, after she was finally given a passport. She now lives in Los Angeles, and performs to adoring Iranian fans in the diaspora. In her portrait, an older version of the singer sits in front of a framed portrait of her younger self. Both are dressed in the style of clothes evocative of their respective eras. Googoosh’s heavily made-up younger version of herself wears a distinctive 1960s bob, while the singer appears more subdued a couple decades later. Time has passed that will never come again.

Found Photographs

For source material, the artist trawled through internet search engines and used found photographs of her subjects. She painted egg tempera on calf vellum, with a squirrel-hair brush, which suggests art rooted in both the aesthetics and the working practices of the past. The resulting portraits were influenced by conflicting art history traditions. In the ornate settings of Persian miniatures, more attention is often paid to the background. The stylized figures in the miniatures show little or no emotion. This is the opposite of Christian martyr paintings of sad, tortured saints. The Shi’as too have their own version of this kind of visual culture: popular religious posters, sold in Iranian bazaars, often celebrate Husayn’s martyrdom at the battle of Karbala.

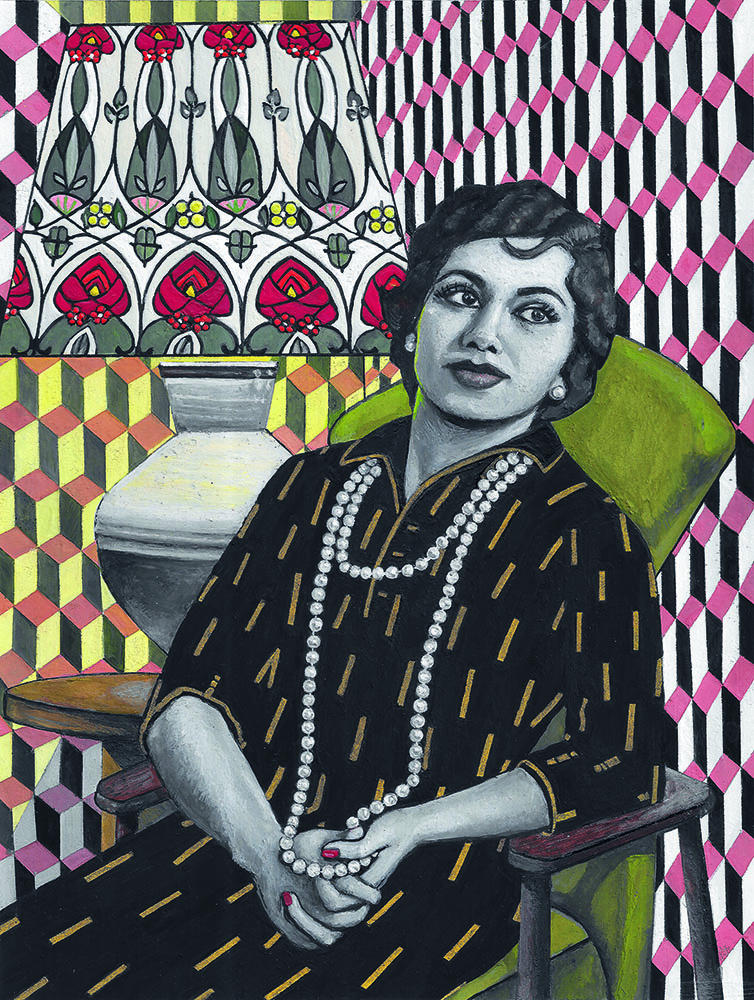

Another singer, Farhdokht Abbasi Taghany (1934–1991), known as Pouran Shapoori, appeared in films and television, and sang more than 32 hit songs. Like all but two of the interior settings of the portraits in the series, Pouran and Googosh sit amidst a kind of patterned splendor. (The exception is Forrokhzad’s white backdrop and the gray behind “The Lor Girl,” Roohangiz Saminejad (1916–1997), the first unveiled Iranian woman to appear in a Persian-language film, in 1933.)

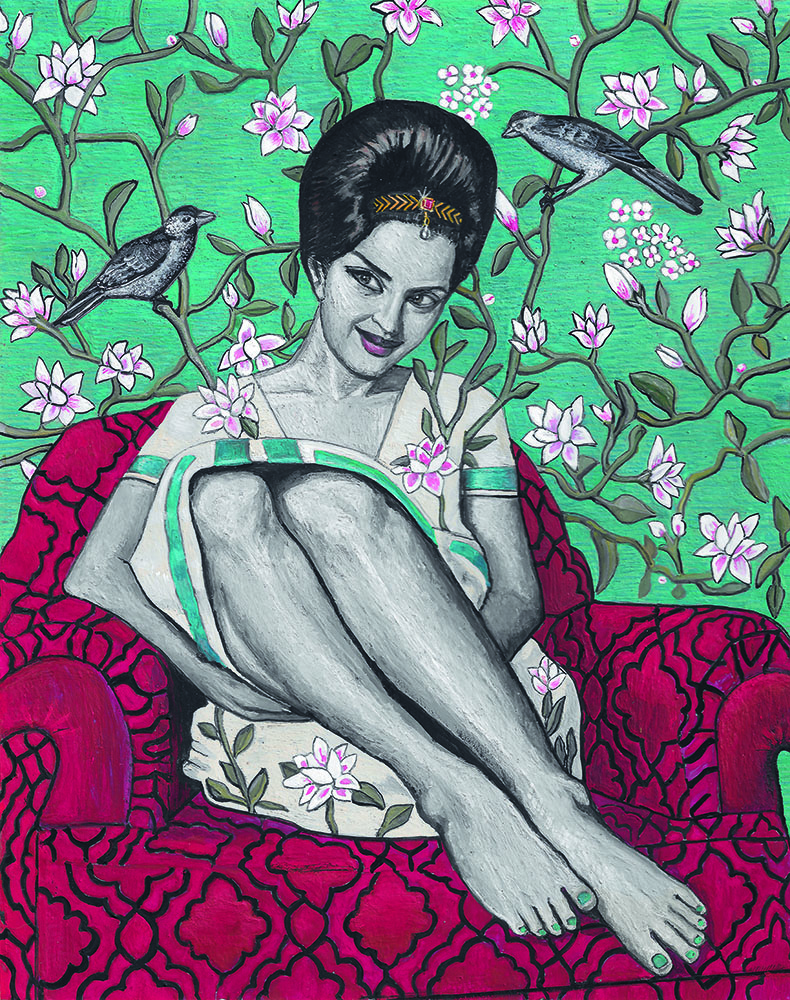

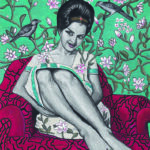

The floor of Googoosh’s portrait resembles the Islamic geometric shapes that cover the Curve Gallery. Barefoot Pouran in “Wild at Heart,” dandles her legs on a decorative red sofa. The wallpaper behind her is ornate, the flowers of which seemingly fall onto the singer’s dress. It is an optical illusion of sorts; the flowers are corsages.

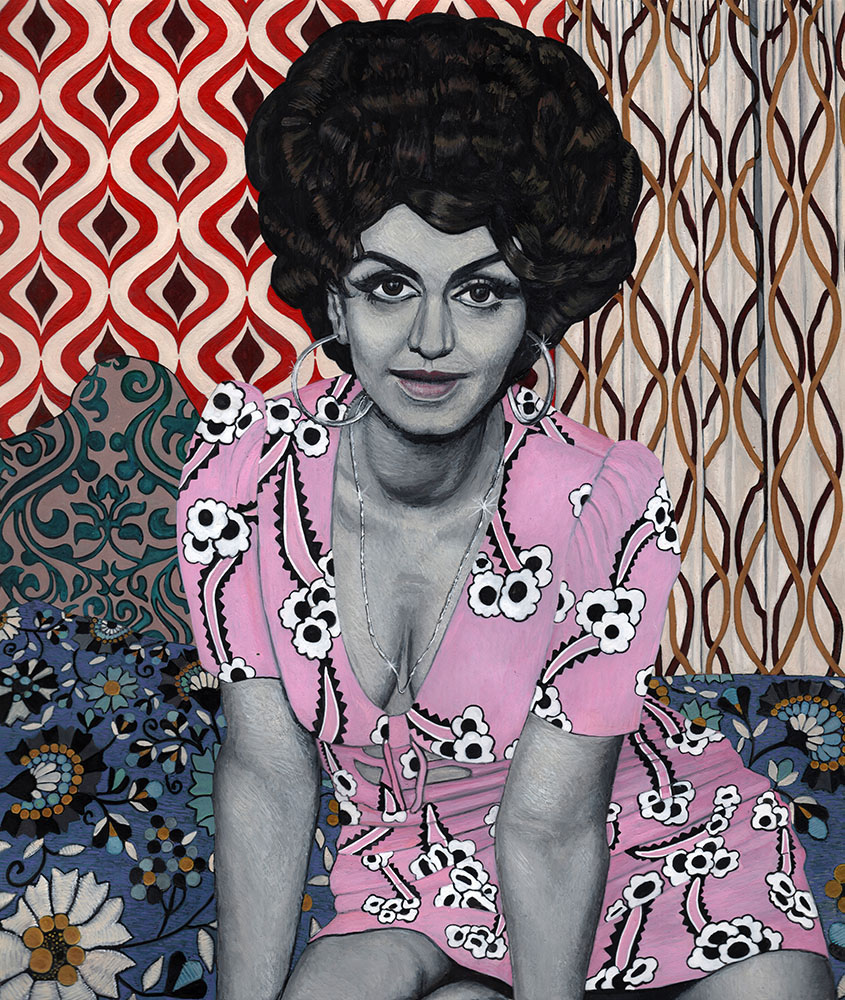

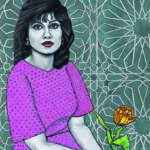

The clothes the women wear, as in the portrait of Filmfarsi superstar Forouzan, Parvin Kheirbakhsh (1937–2016), enhance the portrait’s story. Forouzan, considered one of Iran’s most alluring actresses, worked on sixty films. During her career she was subject to the desires of men, both secular and religious. In the exhibition guide to Rebel Rebel, she is quoted from a 1972 interview as saying, “I am sick, sore, and exhausted. I am tired of standing in front of the camera listening to the director telling me ‘be a little sexier, a little more lustful, bring your skirt higher, be a little more inciting and provocative.’” In her portrait, “Hey, Baby. I’m a Star,” she wears a modestly revealing pink flowered dress, her expression forthright and open. After the Islamic Revolution, the authorities released her from prison once she signed a letter of repentance. However, her money and property were confiscated and she died in obscurity.

Sartorial Upheaval

The decorations and shapes in the women’s clothing and interiors — in some cases landscapes — where they sit, as well as in the physical space of the gallery itself, are key to Sokhanvari’s visual vocabulary, which stems from family culture. Her father, Ali Mohammed Sokhanvari, was a tailor during a period of great sartorial upheaval in Iran. In 1936, the first Pahlavi King, Reza Shah, issued the Kashf-e hijab edict, which ordered women to no longer veil or wear the chador. It was part of new and evolving laws, which replaced female and male traditional attire with Western clothing, including the “Chapeaux Hat” for men.

In the 1940s, Sokhanvani’s father taught himself the new clothing styles by going to the movies. At the cinema in Shiraz, which showed western films, he spent the whole day there sketching the outfits of Hollywood film stars, which he then reproduced at home. In the exhibition catalogue, Sokhanvari tells Barbican curator Eleanor Naire about her mother’s version of the black dress and yellow coat, with black buttons, worn by Audrey Hepburn in the 1961 film, Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

The artist reveals, “I used to float about my father’s office, where there would be tons of sketchbooks with fabric samples and rolls of fabric resting against the walls. I image that’s why patterns and colors play a major part in my works. He taught me how to draw and paint — I owe him that too.”

Like many Iranians in Britain, Sokhanvari is a dual national. She was unable to return to Iran and therefore did not see her father before his death in 2021. Fabrics and Islamic geometries may be part of reconstructing memory and home, but the politics of dazzle is not lost on the artist.

“By pattering the walls and floor of the gallery, I’m inviting the viewer to step into one of my paintings. I’m inspired by Islamic aesthetic philosophy, in which architectural surfaces are intensely ornamented. What you could call an ‘over-beautification’ creates a delirium for the viewer so that they lose their sense of self and encounter God.” As influences, she references Simone Weil’s experience of beauty as “radical decentering” and Elaine Scarry’s “opiated adjacency.”

Sokhanvari goes onto admit, “My intention is to create a space to dazzle the onlooker so that they can contemplate these women.”

Psychedelic Social Reality

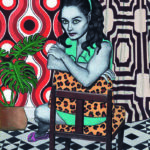

In the essay “A Constellation of Stars,” art historian Dr. Jordan Amirkhani sees Sohanvari’s intense patterning as a kind of caging of women. She cites as one example the portrait “Only the Sound Remains” for Azar Mohebbi Tehrani (1946–2020), the singer Ramesh from the golden age of Iranian pop.

Amirkahni writes, “These patterns seem to pin the women in place, reflecting the ways in which women were indeed ‘caught’ within a web of conflicting social practices; this was a web that reproduced oppressive gender roles and derailed pathways to activism and emancipation for Iranian women, many of whom were eager to fulfill the liberatory potential of the state’s progressive social mandates … [It was] glamorous on its surface but disorienting in reality … In a society unable to negotiate the clashes between clerics and culture-makers, women’s freedom to create and express was rendered precarious.”

Amirikani also discusses Sokhanvari’s deployment of “the histories of geometric patterns found in Islamic art alongside the campy, stylized aesthetics adopted in Iranian popular culture of the 1960s and 1970s, acknowledging a truly psychedelic social reality.”

This reality is one the artist experienced firsthand after she left Iran. Months after the 1979 Revolution, sick in a U.K. school, she waited for the nurse, while a television next door showed images of violent protest in Iran. The volume had been turned down at the same time music from the school’s dance class filled the air. “From that moment on,” writes Harriet Shepard in W Magazine, “Sokhanvari’s every memory of the revolution has been recalled to the beat of ‘Boogie Wonderland.’”

Music is an important component of the exhibition, which was named after David Bowie’s 1974 song, “Rebel Rebel.” In the Curve Gallery, a chill-out area with cushions has been provided for those who wish to immerse themselves in a poignant soundscape by Marios Aristopoulos. It features the voices of Iranian women and music by Ramesh and Googoosh at a time when women singers are still banned from performing live or being broadcast inside Iran. Above the cushions hanging from the ceiling is the sculpture, “The Star.” Fashioned from Perspex two-way mirrors, wood, metal, plastic and electronics, within its see-through interior a monitor plays videos of the singers of the day. Sokhanvari’s use of mirrors recalls the glass-cut sculptures of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (1924–2019), who revitalized the Persian folk art tradition of Āina-kāri.

Cosmic Dancers

Not every woman in the exhibition is a victim. Pouri Banaaei (b. 1940), a star in early Filmfarsi and later in Iranian New Wave classics, stands, hands on her hips, gazing confidently towards a distant horizon in “The Immortal Beloved.” She towers above the tree line of a mountainous landscape. Banaaei had notoriously refused to sign the regime’s letter of repudiation, saying she had done nothing wrong, and went back to ordinary life.

Sokhanvari plays with women’s visibility/invisibility in “Cosmic Dancers I and II,” two installations consisting of viewing, octagon boxes made from wood, metal, PVA, acrylic sheet, car paint, emulsion paint and electronics. Looking in from one side of the boxes, a figure of a woman can be seen dancing inside. Peering in from the opposite side, the figure has disappeared.

But Iranian woman have not disappeared. They are out on the streets. As I gaze into the compelling eyes of Sokhanvari’s rebellious women, I can’t stop myself from thinking about a tactic of the regime’s, shooting protestors in the eyes, and the call to ophthalmologists the world over to lend their aid and expertise to wounded Iranians, who are too scared to go to state hospitals for fear of arrest.

Sokhanvari has made sure that the faces and stories of these inspiring cultural icons have not been lost — and the spirit of these women will inspire those who come after them.