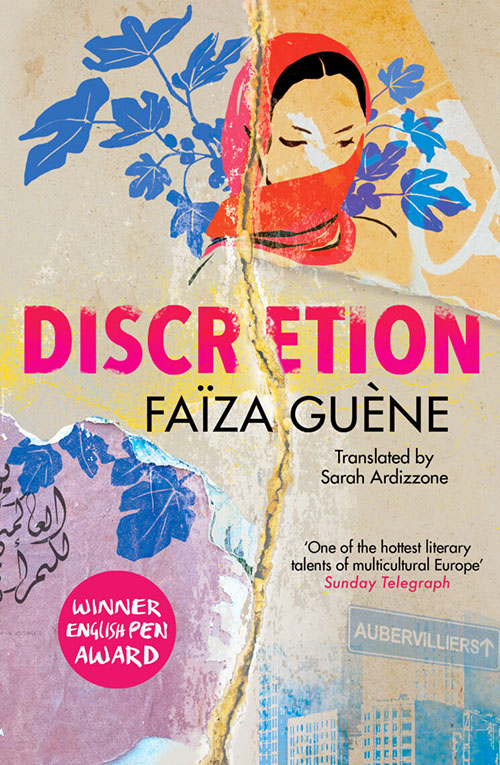

Back in 2004, a 19-year-old French novelist of Algerian heritage named Faiza Guène shook the French literary world with her debut novel, Kiffe kiffe demain (published in the UK as Just Like Tomorrow). The teenager from a disadvantaged suburb of Paris sold over 400,000 copies of the novel, which was translated into 26 languages.

16 years and five books later, in 2020, the author published her sixth novel. La Discrétion tells the story of an Algerian mother (Yamina, 70), her husband, and their four children in Aubervilliers, a northeastern suburb of Paris, and is inspired by Guène’s own family. The novel has been translated into many languages, including English, and has received praise in the UK and the US.

Melissa Chemam

Melissa Chemam: Your latest novel, Discretion, was published in English last year and received positive reviews. With your first novel Just Like Tomorrow, you enjoyed international success in 26 languages. Do you feel that you are better received abroad than in France?

Faïza Guène: I will say this, being fully aware that an author born in England and hailing from elsewhere, from the British colonies, say, would perhaps feel the same way I do concerning France, were he to be received in France — yes, abroad and especially in England, I always feel that I can express myself freely on the subjects I like, in my writing. It is one of the countries that has supported me the most, and where readers follow me particularly. Here, I am received with a slightly less limiting perspective.

TMR: Isn’t this one of the crucial points in terms of how your books are received? These questions of “where does literature begin” and where does “the social phenomenon” that feeds it end?

Faiza Gùene: It’s true, and for a long time I had this feeling of having been left out of the “universal” in a certain way, in France, because I was stuck in all these social problems, from my first novel, Kiffe kiffe demain. I did not reject these problems, because they are obviously part of my journey and my work. But they have become limitations. Now, I feel much less limited. First of all, I’m getting older. I’m 37, so fortunately the reception of my books is different. And then, after six published novels, I think that in terms of legitimacy I have fought enough as it is. And my other projects in parallel have given me a more solid foundation, especially the screenplays.

TMR: You started writing at a very young age, as a teenager, and to be 37 years old with six novels is prolific. Do you feel that you’re now at a mature stage?

Yes, and moreover I took time between each novel. I think that with the experience of age, of writing these six novels, I can’t be treated like I used to be. I’ve often said, they treat me like they do musicians who make a summer hit and then disappear. As if my first novel was the equivalent of “La Macarena.” Now that’s over. I have experience. At the same time, I know it’s normal, because I wrote my first novel when I was 17. Since then, my vision of life has changed: I have written these books; I have become a mother. Everything I’ve experienced, within and beyond my career as an author, makes me write differently today. 15 years is a long time.

TMR: One of your teachers encouraged you, but did you think you had a career in literature ahead of you?

Oh no, that’s for sure. I never imagined that I could make a living from writing when I started. I loved writing, I’ve always written, and I wrote fiction, with the confidence to make it fiction. It was a way to escape from reality, from childhood. It was something I enjoyed. And it wasn’t in the sense of survival or therapy; it was my hobby.

TMR: Were there any authors who inspired you then, who were part of your youth?

Very young, not really, to be honest. I’ve been asked this question many times, and I could tell a great story, but honestly, as a child, no. I started reading in school, and then I read some more serious books as a teenager. One that stuck with me was J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. I often talk about Émile Zola. And later I discovered James Baldwin. As a child, I was more inspired by the life stories of the people around me.

TMR: Following the immense success of your first novel, did you take on other roles, such as teaching, social work, or something else? Or did you become a full-time author?

Yes, in a way. But I didn’t stop my studies either, as some people think. I had already started working at the age of 16, to help my family, before I signed a publishing contract. And I was bored at school then. I became a full-time author first because it occupied all my time, concretely. And as a result, that’s all I did, especially when I started making a living from it, as soon as Kiffe kiffe demain came out. It didn’t last long, though, because I didn’t invest my money properly. For me at the time, it was an episode in my life. I didn’t think it was the beginning of a career.

TMR: And have you changed your way of life? The Seine-Saint-Denis suburb of Paris, for example, is very important in your stories; have you continued to live there?

I still live in Seine-Saint-Denis, until today, even though life has changed. There are organic stores now next to my house; we’ve been visited by gentrification, but I haven’t changed my life, really. Even though I’ve sold a lot of books, I haven’t made millions. People often refer to my career as “trans-class,” but novelists are not footballers. Success is different in different circles. After a success with a novel, you have to keep up. In my family, we don’t have a heritage. I started out at minus 1000. So obviously, living on that success for five years is already enormous. I was able to pay rent and take care of my family, without anything excessive. I didn’t blow my money; I was just able to live. And that obviously allowed me to continue writing.

TMR: And what is your family’s relationship to your books?

If you knew my family, you’d understand why I have to stay humble. Life went on as if nothing happened. In between official invitations and TV shows, I would go home and wash the dishes because it was my turn. There was no difference in my parents’ pride in me or my sibling. If anything, it was less than my brother. They had no disdain for literature, but no fascination either. They were just very happy to see me doing what I love. Of course, they feel a respect for everything that has to do with books and writing. For my mother, for example, who had to drop out of school, like the main character of Discretion, her great wound was not to have been able to continue her studies. So, she was encouraging. But success and fame were not the issue. What mattered to them was that I was doing something respectable. At the same time, my parents and family don’t really understand my profession, not totally. So that kept me down to earth.

TMR: You’ve worked a lot with your mother. She participated in your first short film, when you had to replace the original actress at the last minute. Was that a natural thing to happen?

Yes. I have a mother who transmitted to me, without being very conscious of it, feminist values in terms of the freedom, the confidence she gave me. And my father also transmitted that to me. They let me do what I wanted to do; they never stopped me from anything. They trusted me.

TMR: This is reflected in your latest novel, where there are never any clichés about Muslim and/or veiled women. The women are presented as very different, sometimes even extreme; one refuses to marry even as her sister chooses a kind of arranged marriage. But they all make their choices. Is this what you wanted to show — a culture that lets women choose?

Exactly. The issue is not to choose for them. It’s not about veiling them or revealing them that helps them. The whole idea of this book and even everything I write, what I want to show, is that I gravitate toward complexity. We have the right to be complex, sometimes to suck, sometimes to be mediocre, like other French people. Sometimes they are! But we, the children of immigrants, don’t always have these basic rights. This relates to the question of representation. Why do we have this pressure to shoulder some kind of responsibility when we come from a working-class background? When you are a woman, or of Arab origin, here in France, I have the feeling that you are not allowed to be complex, different or even bad. We are obliged to be excellent because otherwise there is no place for us.

TMR: And what is your relationship with the culture of your parents? Do you go to Algeria often? Do you speak Arabic?

It is my mother tongue! I speak it every day. I am very close to my original culture. And I’m getting closer and closer to it as I get older, because I have children. I had my first daughter at the age of 25, so quite early in my life. And so there was very early on the necessity of what I want to transmit. The language is part of it. The culture of my parents, too. This is also explained by the fact that we went to Algeria a lot when I was little. And I was convinced that we would return to Algeria one day: my parents, me, my brother and my sister. I think that the history of my parents plays a role; my father was born in 1934, and my mother in 1949. So, I have issues from the generation before, because of the huge generation gap between my parents and me (I was born in 1985).

TMR: You talk a lot about your family in your books, and always with a lot of love and respect, even admiration, despite all these traumas. And, if we are honest, we have to say that there is almost a trade in trauma in the literary world, especially when we talk about decolonized countries, such as Nigeria or Algeria. Yet in your books, there is, above all this, love. Is this due to a desire to be authentic? Or does it just come to you?

It’s not even a thought with me. Again, the only thing I tell myself when I write is that I want my characters to be right, to be true. I write them with sincerity. Afterwards, with the analysis and the feedback from the readers that I’ve had, I’ve realized that. And it’s like that with every book. With Kiffe Kiffe demain, I’ve been told: “You finally give a positive vision of the suburbs.” But […] I faithfully recounted what I knew according to my own experience. And with this last book, it’s the same thing. I didn’t try to do something revolutionary by dealing with characters that were nice Arab men. It’s that, in fact, they exist! That’s what’s so terrible about it: You never see them in literature or on television. With the usual deficiency and misrepresentation, when you try to be a little fair, it’s perceived as something extraordinary.

It’s also my way of seeing this story. That’s what excites me. The possibility to change the perception of this environment a little bit, to be a little bit indulgent. I can speak for example of the character of Malika in my last novel, who marries at 17 because her parents help her and arrange this union. They do what they would have done in the village because they don’t know how to do it otherwise, because that’s how it was done there. And it makes sense to her. She agrees to get married like that, almost as a courtesy. She has nothing against it; she is even quite shy. Others could talk about forced marriage. In France, in the 1980s, there were many debates on the subject. Looking back, I find it incredibly racist and paternalistic, where French politicians proposed to save all these young Arab girls, without knowing what was best for them.

TMR: Were they seen in an exoticized way? And was the violence of the so-called French social reality in the suburbs blamed on the parents’ culture?

Of course. I explain this, in my fiction, through a burning desire of the parents to retain the little that they brought with them, that is to say, their culture, their traditions, their history, their way of doing things. Because it is so brutal when you uproot yourself. Because these immigrants and exiles have had a thousand mournings to make when leaving. The mourning of tradition, the mourning of religion, the mourning of language. It is so painful. Perhaps those who were very conservative were that way because they wanted to keep what constituted them, and to transmit it to their children. So, of course, some of them were sometimes clumsy. Others were violent, others brutal, certainly, but I like to think that I will dig a little bit in that area to understand. It makes us forgiving, and that’s why I like the character of Malika, because there’s a kind of gentleness in her in the idea of saying, “My parents, they did what they could.”

TMR: After coming up with characters that seemed never seen before for your debut, was it difficult to write the second and subsequent novels?

No, and moreover I want to say that there have been other such novels before mine, and several waves, several generations of authors who have written on the subject before me. I point this out every time I can. There are other authors of Maghrebi origin in France who have evolved in different times. Of my generation, especially as a girl, one can say that I was a little pioneer. But before, in the previous generation, there were authors such as Tassadit Imache, for example, author of the book Une fille sans histoire, published in 1989. It is another time, but it shows that there were people who emerged.

Unfortunately, the literary world tends to extinguish success as quickly as it engineers it, and we treat these authors as a social phenomenon. Also, because fame can be so short-lived, oftentimes the newer generation does not know anything about earlier writers. But I often think of those writers, of people such as Mehdi Charef; they did a lot for previous generations and they wrote for us too. The problem is that we don’t quote them; we don’t talk about them. But I am not the first, that’s not true. There was also Rachid Djaïdani a few years ago, with Boumkoeur. They are different universes, but we are in the same space, of this in-between of children of immigrants who tell their moments of life. [Cf Les Savauges and 404 by Sabri Louatah, ED.]

TMR: And these are authors that you discovered with difficulty?

I discovered them too late, yes, quite late, whereas I should have found them more easily because I was looking for that. I grew up in France, where they were largely ignored, so how could I hear about them then? I wish I had heard of them and claimed them as my own when I started writing and getting published.

TMR: In France, we often expect authors to be professors of literature, to claim an institutional affiliation of some sort, but you didn’t have such a thing, right?

Exactly. As a result, I have been denied a certain legitimacy. But there was only one book at home, the Quran. And that’s what led me to have a sacred relationship with books. Just the way my mother [physically] handled it made an impression on me. On the other hand, we had thousands of oral stories, and that allowed me to value our culture. In a dual culture, it should not be the case that one is valued and the other devalued.

TMR: Do you feel that the French tend to devalue North African cultures?

Yes. The feeling is related to the resentment of lost glory. When they see us, they think of their lost grandeur and empire. For our generation, there are still colonialist legends, even about the Senegalese or Algerian riflemen who loved the French empire so much that they wanted to defend it, but in fact those poor people just didn’t have a choice. And in 2022, with the 60th anniversary of Algerian independence, we witnessed a monopolization of the word, by the French, the pieds noirs and their descendants. All the stories are put on the same level. We, Algerians, have finally conquered a little space to make our stories and our voices heard, but the dominant narrative still colonizes these spaces. As if the grandchildren of the colonists are doing the same thing to us, in a symbolic way. To me, this is unbearable. It is indecent because you cannot compare the suffering of the colonized and the colonizers. Not to mention the cultural appropriation, the French who produce documentaries on Algerian music, without including any Algerian. For me, this perpetuates colonial appropriation.

TMR: Is this what led you to write about the story of Oussekine (a young Frenchman of Algerian origin killed in 1986 by the police in Paris) and other more difficult episodes in Franco-Algerian history, such as October 17, 1961?

My little documentary on October 17, 1961 was actually my first project, even before my first novel. I met a historian of this period, Jean-Luc Einaudi, for example, and I didn’t let myself be trapped by critics who tell us that we are too close to the subject. I didn’t let myself be dissuaded from speaking by “intellectuals,” politicians, or historians. It’s my good fortune to be a self-taught person. I speak only from my intimate point of view, as the daughter of a poor Algerian worker.

Many Algerians and French of Algerian descent have too often been left out of storytelling projects, books, podcasts, etc. Suddenly, it became cool to be Maghrebi or traumatized. With Oussekine, we wanted to tell the story from the family’s point of view and we worked with them, as close as possible to their experience. We succeeded in telling a unique story — not the whole story of police violence, just that of Malik Oussekine. We did not want to appropriate a discourse, but to give the family the chance to express themselves. In the first episode, we compared the police methods of the 1980s to those of the colonial era and October 17. French counter-insurgency methods were the same in the 1950s, during the Indochina War, the Algerian War, and quite similar to police methods in France itself in the 1980s and 1990s. This colonial sort of violence in the metropole made the Muslim community feel segregated, and even fostered terrorism.

TMR: In your novels, this is also expressed?

Yes, they express the impossibility of conveying our sufferings, of transmitting the truth about colonial violence, without being accused of victimhood. I am often told that I am the one who is obsessive. But I have the impression that I am hardly heard. Yet the great American or Western narratives, when they repeat the same themes, are described as profound.

TMR: Discretion is less light, less comedic; was it time for such a work?

I allowed myself to be more expansive, to write for my people, to go into a more autobiographical story, which my mother had told me. But I also discovered episodes, by asking her to talk about her childhood memories. For example, when she told me that a French soldier threatened her family by pointing his rifle at her baby brother. These are not trivial memories; they are traumas once again. The impact of the unspoken, of the repressed word, has long worried me, in my life, as in my literature. What is difficult is to make the link between how one is, how one lives, and the great family and political narratives. This novel is a small step on that path.