Yussef El Guindi

When it comes to countering the implicit, and sometimes explicit prejudices that the larger society exhibits toward Arabs and Muslims, American theatres are not particularly ahead of the curve. While some theatres have bravely and commendably gone out of their way to address the deluge of negativity the mainstream culture exhibits towards most things Middle Eastern, those theatres are rare.

Prior to the 2000s there were few to no representations of Arabs or Muslims on American stages. I grew up in the UK and the US and never once saw myself represented in the theater. I never saw a play by an Arab or Middle Eastern immigrant. We were never counted among the cultural workers in these countries. When there wasn’t a cold indifference, there was an antipathy to our stories.

This is disappointing. One expects theatre to rise above the crassness that swirls through the currents of mainstream culture. You would hope that theatres espouse values that more commercial fare might shy away from. You want theatre—especially nonprofit theatre–to champion values that might interfere with the bottom line. Not that we want theatre to lose touch with a wide audience, lest it become perceived as being even more elitist than it already is. Crassness, after all, can be fun.

Theatre has some of its roots firmly planted in the mud—in the foibles and weirdness of human nature. “Rising above” mainstream culture doesn’t mean theatre should eschew any of the broad, popular memes currently in circulation in it. By all means artists should feel free to infuse their work with whatever is most fashionably current, in style, aesthetics, popular thought, songs, etc. But theatre should also have a critical eye; it should offer up critiques, contextualize, and provide some kind of critical framework through which to view the culture and politics of the day. Because most theatres are nonprofits, they should be more daring in terms of the subject matter they choose, staging stories and perspectives that might be hard to find elsewhere.

This is the ideal. And given this ideal, expressed by many theatre mission statements, I wonder why there aren’t more plays by and about people who come from the Middle East. Never has any one area of the world had more impact on the U.S. than the Middle East. Repeatedly. Every year for as long as most of us can remember.

In every decade of my life, Arabs and Muslims have made headlines in some capacity (almost always in a negative light). One gets a little punch drunk during some news cycles dealing with this (from my perspective) battery of biased reporting, in which Arabs and Muslims end up always coming across as seemingly genetically prone to mindless violence, wars, the oppression of women, etc. The go-to images are always large mobs of angry Arab men, veiled women, bearded Muslims in prayer, bombed sites, and so on. I have spent most of my life being gobsmacked by all this, contrasting what I see in mainstream American culture with what I live and know when I travel back to Egypt and hang out with friends and family and imbibe the culture around me.

Quite naturally, in a desire to make sense of all this, I turn to the arts as one potential source to put some of these Middle East happenings in perspective. I want to step away from the objectionable “objective news” and the biased pundit class with their conservative think-tank opinions, and see how the culture around me processes these events.

I hold out little hope that movies or television will give me the other side of the story. Black-and-white perspectives sell more tickets than grays, or rarer still, viewpoints directly from “the enemy.” The best you can hope for in a popular movie that deals with the Middle East is something akin to the “cowboys and Indians” narrative, in which the vast majority of the “Arabs” are portrayed as menacing and hostile, except for the “good Arab” who sides with the West and aids its agents in fighting a particularly nasty leader and his fanatical hordes. In movies, money follows prejudice because simplifying the world into “us” and “them” is more satisfying than having to deal with all the ambiguities and qualifiers that are part of most people’s daily lives.

I expect more from the stage. But in the American theatre over the past 15 years, for all its talk of wanting to be inclusive, I have rarely seen plays that address what’s going on in the Middle East or what is happening to Muslims and people of Middle Eastern descent here in the U.S. (leaving aside the almost total absence of such plays before Sept. 11, 2001). The Ancient Greeks made it a point to address their wars in their dramas. Why is it that American theatre, with rare exceptions, should fail so drastically in this regard?

It’s an oft-repeated observation of American culture that people don’t like politics in their entertainment. It is outside the limited purview of this essay to explain this aversion to political theatre in the U.S. But the fact remains that a whiff of politics will expose you to the charge of having an agenda, of being too didactic or preachy. While my plays often present the outsider’s perspective, I’ve never written a play that expressly dramatizes the points I raise in this essay. As much as some critics like to say I have an agenda, I don’t when I write for the stage. It’s all about characters and their wants. Now obviously these characters are consciously or unconsciously pickled in the brine of my political outlook, so to speak, so some of my personal concerns will find their way into the play, but these characters are not mouthpieces for me.

It’s odd that, by contrast, a small island like England can create big-canvassed plays that address their political culture and their standing in the world, while the U.S., a world power and a country that surely begs for ambitious plays, mostly produces small, insular plays that deal with matters of the hearth and heart. It is often argued that some types of navel-gazing can be deemed political. Or to use a common phrase, the “personal is political.” A domestic drama may be said to act as metaphor, encapsulating larger political concerns.

But most of the time, the politics are so deeply cloaked in metaphor that they can be safely ignored. It’s a repeated oddity that the American protagonist rarely seems to care or understand his or her place in the historical and political forces at play. As a consequence, the default setting for American drama is generally warm (matters of the heart predominate), uplifting (dreams can be realized in spite of obstacles, and if they’re not it’s an American tragedy), and domestic (the individual is paramount), with just enough social commentary thrown in to give it a little bite.

The problem is that for most people outside of the West, active politics is part of their daily life and conversation. To self-realize, to pursue happiness, means having to pay attention to government policies and how they affect you. You can’t do too much navel-gazing when bullets, tear gas, and arrest are real possibilities, or if you’re simply trying to gain basic freedoms and human rights. Consequently the home life of a lot of Arabs and Muslims is filled with political chatter. To dramatize the daily lives of these two groups (and quite a few other non-Western peoples) is to unavoidably include the political element as part of normal domestic interactions. Here the personal truly is political.

Americans are so averse to politics in their entertainment that the simple act of including Arab or Muslim characters in a play exposes it to the charge of being overly political or didactic. And if the play is written by an Arab or a Muslim? The writer must surely then be peddling some political agenda. Even if, for example, the play revolves around the ordinary family dramas of an Arab or Muslim family, as in my play 10 Acrobats in an Amazing Leap of Faith, though nothing political is uttered the play is regarded as making some kind of statement. Or worse, the play gets dismissed as social activism rather than being judged on its artistic merits. The very act of rendering a group of people usually depicted negatively in a three-dimensional way is deemed a political act. Whether the writer intends it or not, they’re seen as trying to “address” something, to right a wrong.

Such criticism has been leveled at some of my plays, even though, as I say, I never have a conscious political agenda when I set out to write a play. Like most playwrights, I am focused on seeing to the needs of my characters. I am focused on craft and character passions, not on trying to sneak in some political agenda, or to have a character wield a political axe I’m grinding. Where’s the fun in that? I’m always surprised when I get critiqued by a reviewer for having some calculated agenda, as if the play was written as a platform to express my political views.

Artistically speaking, Arabs and Muslims are in a predicament in the theatre. We can not walk onstage unburdened by the political framework in which we exist offstage. As a group we are fraught with all the accrued bad news heaped on us. As characters in a play, regardless of what we do, it’s hard to shed the manufactured political narrative we’ve been assigned. Existentially, and dramaturgically, we’ve become politicized. While other characters can come onstage with a question mark hanging over them as we wait to find out who they are and what they want, with Arabs and Muslims our entrance sets up a set of expectations, usually all negative—which these characters will either subvert (at which point the political-agenda accusation might be brought up) or confirm (at which point the play might then be safely celebrated, since the audience’s prejudices have been validated).

This scapegoating echoes the way other ethnic groups have been treated onstage in the past, and often still are. African Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Latinx characters have historically made stage entrances carrying their share of political baggage. Baggage that is spilling over with other people’s stuff, not their own. The political burden attached to these and other minorities has begun to lessen as more varied depictions make their way into the mainstream culture. It takes a while, and the struggle to unpack that baggage is still ongoing. But for Arabs and Muslims, that unpacking has barely begun.

Arabs and Muslims—even in liberal, Western eyes—have come to embody the sins of patriarchy, sexism, religious fanaticism, mindless violence, and machismo of a kind that is seen as particularly dark and menacing. Never mind that these sins are as rampant in other groups all over the world. In Jungian terms, Arabs and Muslims are (currently) the groups upon which others get to project their “shadow” elements.

In theatre’s fitful embrace of multiculturalism, then, Arabs and Muslims have rarely been included, as we tend to fall outside the multicultural comfort zones. That’s because multiculturalism as it stands now often operates as a depoliticized zone, a place where “diversity” has been smoothed over to appeal to the greatest number of people, with the least amount of friction. Commonalities are sought, differences ignored or smoothed over. It’s a way to bring people out of politics and into a gentrified history. If you can’t be gentrified or depoliticized in this way, you can’t be welcomed into the multicultural fold. Arabs and Muslims, it seems, will have to wait in the wings until we can somehow shed the disconcerting political trappings that currently hang over us.

Or perhaps the trajectory of an ideal like multiculturalism is inevitably to open up to ever more inclusivity. I’m enough of an optimist to believe that the promise of diversity will eventually have to include the voices of the nearly two billion people that comprise Arabs and Muslims in aggregate around the world. I believe that more and more theatres will start to program plays by and about Arabs and Muslims, as some already have. But it’s only likely to start happening in our nation’s regional theatres when Arabs and Muslims can be seen as fully dimensional people, not as mere triggers or symbols of political controversy.

It largely remains true that a whole people and religion have been locked into very specific and negative narratives, and so it becomes very difficult for an audience to see beyond the headlines. They don’t know what they’re looking at, or why they should pay attention, when the whole point of bringing in all these marginalized voices in from the cold and onto the bigger stages is to foreground the very the thing that has been stripped from them for decades: their humanity. Watching an Arab fry an egg, for example (why not a breakfast of shakshouka), may be the start of a very funny play (or drama) that introduces an audience into the lives of people with concerns very much like their own. Which is very much the impulse behind all stories: to communicate an experience and bridge a divide.

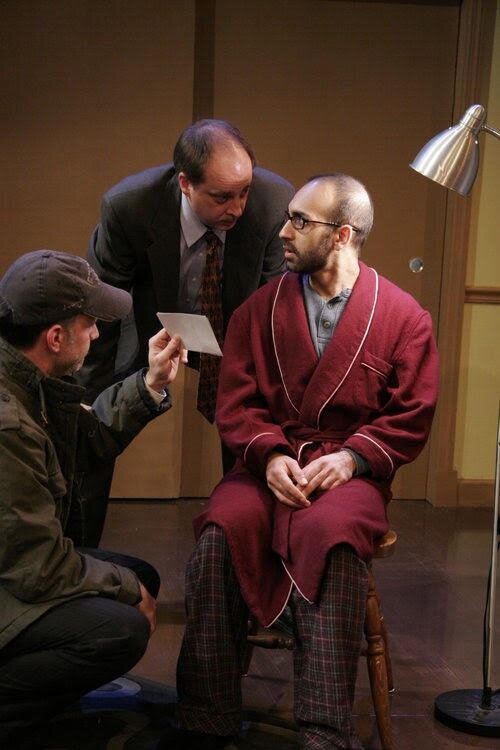

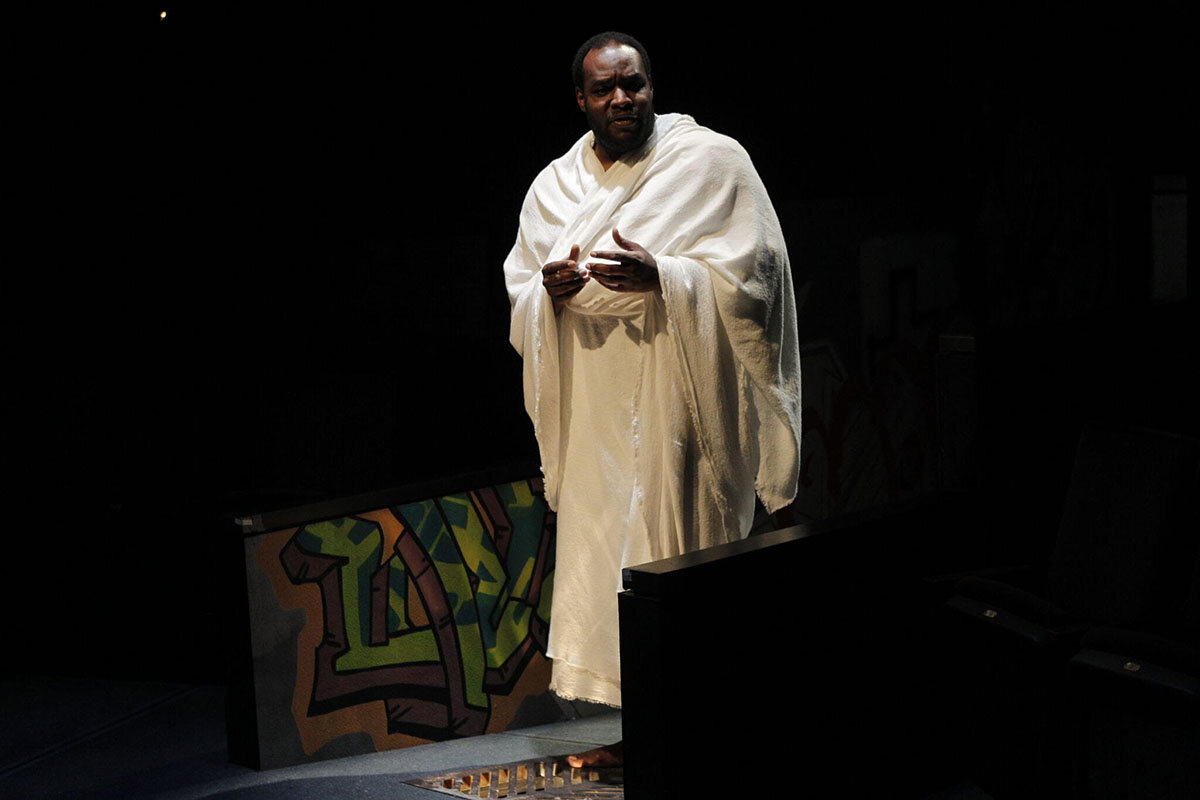

Yussef El Guindi’s most recent productions include People of the Book at ACT in Seattle, The Talented Ones at Artists Repertory Theatre in Portland, and Threesome at Portland Center Stage. Bloomsbury/ Methuen Drama recently published The Selected Works of Yussef El Guindi. He is a prolific Arab American playwright of Egyptian descent whose works have been produced across the USA since Back of the Throat first premiered in 2004. He writes full-length, one-act, and adapted plays that focus on the Arab/Muslim experience in the United States. El Guindi has been the recipient of many prestigious playwriting awards including the Steinberg/American Theater Critics Association’s New Play Award, Gregory Award, Edgerton Foundation New Play Award, ACT New Play Award, Seattle Times’ “Footlight Award”, the M. Elizabeth Osborn Award, L.A. Weekly’s Excellence in Playwriting Award, Chicago’s After Dark/John W. Schmid Award for Best New Play, and the Middle East America Distinguished Playwright Award.

Join Our Community

TMR exists thanks to its readers and supporters. By sharing our stories and celebrating cultural pluralism, we aim to counter racism, xenophobia, and exclusion with knowledge, empathy, and artistic expression.

Learn more