As the first person in her Palestinian family born in America, Christina Adranly made it, growing up in a rich town, attending elite schools, and marketing AI for the biggest company in the world. A real American Dream. But when her people’s suffering became inconvenient, she was forced to confront the painful gap between performative acceptance and real solidarity, exposing what it costs to finally refuse the terms of belonging.

I was the first person on either side of my family born in America, on the 4th of July no less. The first daughter, the first cousin. First MBA. First to live in New York City. First to work in creative at the biggest company in the world. First to grow up with rich white girls.

I took a trip to the Adirondacks for the July 4th holiday. We stopped at Loon Lake as the sky sparkled with fireworks. It never gets old. “They’re all for you,” my mom used to say.

My friend read me a Mary Oliver poem that night:

If you suddenly and unexpectedly feel joy, don’t hesitate.

Don’t be afraid of its plenty. Joy is not made to be a crumb.

Growing up, whenever anyone asked me where I was from, I’d say something vague like “Middle Eastern,” or exotic like “Greek,” or mysterious, as in “a Mediterranean mix.” I was thankful to be racially ambiguous. I hesitated to say I was Palestinian, so as not to frighten anyone.

We each had to present a “fun fact” about ourselves during a team kickoff at work, and when I shared that I’m a first-generation immigrant, our GM responded, “Oh. That makes sense.”

I moved to Moraga in third grade. My family kept candy scattered in jars around the house. We always had the best food in the largest quantities at pregame pasta feeds. I loved having my parents host my friends for dinner, a tradition that has lasted throughout my adult life. Look how generous we are. Look how good our food is. We’re civilized Arabs, not terrorists. Look how inviting and close we are as a family. What else can I get you?

I didn’t have the language for it, but I knew intuitively I was something else. I wrote my UC Berkeley admissions essay on how different it felt to have spinach pies and hummus in my lunch instead of turkey sandwiches. I got into Berkeley. Maybe I did have the language.

I’m the family pioneer, the first and best, building on my family’s American Dream. I grew up doing advanced math outside my classroom with a kid I absolutely hated, while all my friends did regular math inside. I was excused from class once a week to do Gifted and Talented Education. A substitute teacher once announced in front of the whole class that I looked like the smartest person in the class. I was captain of every team I was on. I was league MVP and team MVP twice in high school soccer. We won the Northern California soccer championships twice, and I scored both game-winning goals. Contra Costa Times Top 100 Athlete. Winning is standard, unceremonious, my baseline. No pressure.

But success comes as a fragile surprise, born inside me from invisible forces I had no hand in creating. Success feels inevitable but at the same time not my own. I’ve never really understood why I was chosen to inherit these gifts, and why I’m required to bear the burden that comes with it. Sometimes I’d rather hide, so I can be like everyone else. I want the same grace and softness everyone else gets. When you’re capable, people expect you to be endless for them, even if you yourself don’t feel endless.

I’m in a class of my own, and people don’t hesitate to remind me, humble me, and put me on a pedestal. I’m a threat just by being.

If you look up “American Dream,” in the dictionary, there should be a picture of my family. My maternal grandparents moved to San Diego during the 1967 war. Their family name is Harb, which means war, battle, tribal valor, constancy, sacrifice, and they fought for pride in spite of war. My grandmother had had enough of my grandfather getting held up at gunpoint — he worked for UNRWA in Tel Aviv and got stopped every night at the new Israeli checkpoints, for the crime of going home after work. In Ramallah they were rich rich. Like live-in help rich. They opened a restaurant when they arrived in San Diego. My grandmother had never worked. My grandfather had never cooked. The San Diego Chamber of Commerce would declare a citywide sandwich day in their honor. They made it.

My father emigrated with his parents, one brother, and three sisters from Jordan (Israel confiscated my grandfather’s business in Jerusalem during the Nakba). Their family name, Adranly, is incredibly rare and has no known etymology outside an anecdotal tie to a Turkish city, Edirne, known for its annual oil wrestling tournament. Adranlys are concentrated in the Bay Area, where my elders landed after expulsion. A blank slate. A new history to be written. Within a few years of being in the United States, both of his parents died; first his mother, of breast cancer, then his father a few months later, I think of a broken heart, leaving my dad with four younger siblings to provide for in his mid-twenties. He raised three successful younger sisters, and then three children of his own, working at the same union job for over 40 years. He made it.

I ended up studying International Political Economy at UC Berkeley, with a focus on Middle Eastern conflict. I felt like I needed to study Palestine from all angles. It seemed like what I’d learned at home was different from how the world around me perceived Arabs and the Middle Eastern conflict, and I wanted to know why.

My family raised me to value the joy in cooking, gardening, and harvesting. I learned that food can be medicine. You have a cold? Maftoul with chicken soup. Upset stomach? Mazaher. Toothache? Rub some arak on your gums. My grandma and now my aunt make me warak dawali every time I visit, just to make me happy. I can’t count how many summer celebrations feature fresh tomatoes and mint from my parents’ garden. It’s not just about physical healing, but spiritual healing. It’s showing someone you care so much that you’ll go as far as to pick something from the garden, prepare it intentionally, and show up for them when they need it most.

My high school softball team members referred to me and the Black girl on my team as “Minority Report.” Halloween costumes were often on the nose (I was a Muslim woman one year, a Native American several years) or ironically Americana (the Statue of Liberty, for example). I was in on the joke. I’m a civilized Palestinian, not a terrorist.

It was the price I was willing to pay for acceptance, but I didn’t understand the cost of betraying myself.

I honestly didn’t even want to go to Berkeley. It was an afterthought, another box to check accompanied by another $40 application fee. It was too close to home, too alternative, not glamorous. I didn’t even visit campus.

I was all in on a school in LA. One night, during my soccer tournament, my mom and I one night were staying in a hotel. She rolled over in her bed and said, “You’re an idiot if you don’t go to Berkeley.”

It’s one of the only times she insisted I change my mind.

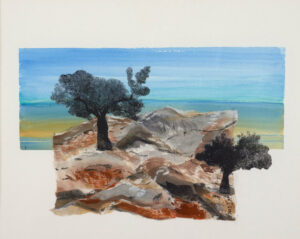

In Apeirogon by Colum McCann, birds fly over a fractured Palestine and Israel like silent witnesses above the constrained lives of (some of) those below. For Palestinians, birds symbolize a freedom they’re denied, unbound by borders, checkpoints, gunpoint, or surveillance. Their flight is a quiet rebellion against confinement, a reminder of what it means to move freely, to live without fear. Birds embody both the tragedy and the hope of Palestine — what is lost, and what might still be reclaimed.

My mom might be the most impressive vestige of the American Dream, for Palestinian girls didn’t go to college back then, so she stayed local at San Diego State for two years. When her brother got into UC Davis, she rebelled, applied to Berkeley, and forced the issue on her parents until they relented. An engineering major, she clawed her way through male-dominated college classes, and was one of only two women to graduate from UC Berkeley with a Master’s degree. She moved us to an upscale suburb in the Bay Area. She’s a millionaire now. I get why she thought I was an idiot for not wanting to go to Berkeley.

I work at Microsoft as a creative strategist, advertising our AI, cloud, and productivity software to large enterprises and small businesses. I love it because I’m inventing the future at the biggest company in the world. Pinch me.

I’ve planned a lot of friends’ birthday parties, baby showers, bachelorette parties. It’s something I enjoy but sometimes I wonder if I’m asked because I’m the most capable or if I actually like hosting.

I was asked by Lucy’s husband to book massages for her birthday. Easy. The request turned into a series of other requests that were “out of scope,” as we say in advertising. What will we do between massages and the dinner that just the two of them were invited to? I was squeezed into hosting a cocktail party.

My friend Victoria is a notorious taker, although sometimes her aloofness earns her a pardon. She was coming in from out of town, and asked if she could stay at my apartment, otherwise she could get a hotel. I let her know she’d be better off getting a hotel — too much else going on for me to manage another task. Twice, she insisted. I caved again.

We returned to my apartment from massages at five, and I had an hour before leaving for my aunt’s birthday to put out cheese plates, fill wine glasses, get towels so Lucy could shower and get ready for her separate dinner, answer the door, get Lucy’s husband scissors and ribbon so he could wrap her gifts, get myself ready for a party. A small ask turned into a crushing burden. No one offered to help. No one brought anything. Just jeers from the living room. Why would she be upset? She should be able to handle this, right? We’re endless fountains of giving with unlimited capacity to host, offer, comfort.

“I’m actually going to just stay at a hotel because you didn’t have enough food for us for dinner,” was the text I received from Victoria on the way to my aunt’s birthday party. I returned to a window left wide open with the rain pouring into my apartment.

The terrorist is the one with the smaller bomb.

—Brendan Behan

On October 8, 2023, my friend Sophie dropped a bomb in the group chat. “I’m thinking of everyone today, how is everyone doing?” How is everyone doing? I imagine I’m feeling differently than the nine white women on this group chat, four of whom are Jewish. I sent Sophie a text on the side. “You know I’m the only Palestinian right?” She encouraged me to speak up. I hesitated. What would I break? I unfurled from a lifetime of contorting myself into spaces too small and unwilling to accommodate me. “I don’t have the luxury of only paying attention when white people die, when we die every day.” To hell with being civil.

https://x.com/InesElhajj/status/1947424977268920403

Scarlett leads product marketing for all of Microsoft’s commercial AI solutions. We were discussing brand messaging and I was asking her to share the strongest proof points for our AI technology. She sent me a PowerPoint deck that she had presented to Elbit that morning. Elbit produces 85% of the IDF’s drones and land-based equipment.

On October 13, 2023, former Hamas leader Khaled Meshaal called for a “day of rage” where he called on Arabs to protest in support of Palestinians. (Media outlets mistranslated Meshaal’s call as a “Global Day of Jihad”). On the same day, the IDF issued an evacuation notice to 1 million Northern Gazans to move south to safe zones. The BBC reported that 97 Israeli strikes subsequently hit “safe zones.”

Gretchen lobbed another bomb in the group chat: “I’m thinking of everyone today, especially my Jewish friends.” Especially my Jewish friends. On the first day Israel began wiping my country off the planet.

Have you ever felt rage that feels calm? I explained the missing side of the “both sides” she was advocating for. “But Christina,” she protested, “I’ve carried water on donkeys in the West Bank. I’ve lived on kibbutzes. I get it. I’m so sorry.”

What a dark honor to educate my white friends on race and racism, and then hand out gold stars when they complete their lessons. What a fucking curse.

Palestinians are known in the West as Christian or Muslim, but really our spirituality is rooted in the earth. It’s in the way we revere olive trees, in the way starving Gazans feed their cats before themselves, in the way the land feeds us when no one else will. This deep, elemental connection to nature is what makes Palestinian spirituality so powerful — we don’t just believe, we’re bound to each other by the elements.

I feel these spirits, I carry them with me.

Birds fly overhead, unbothered, and in their flight I always think of Gazan children. “They’re finally free” I think to myself.

The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion. —Albert Camus

I haven’t been free. Miss Fourth of July, not letting myself be free.

Freedom isn’t bowing to structures imposed on you. Freedom isn’t pleasing your oppressors, even if they’ve posted a black square on Instagram before. I’d rather destroy myself than be reduced. Fireworks don’t explode smaller in the sky because the sky can’t hold their light. What freedom would there be in that?

How do you see dead kids on X and then land a creative strategy for an $80 billion business with Microsoft’s leadership team? How cruel of computers to collapse both into the same portal, to be experienced at the same time. What’s the civilized way to show up for that?

Our spiritual connection to the land is layered and exists in the metaphysical. A living archive of resilience, memory, and communal care, whether we’re bringing oranges from our tree to new mothers, offering coffee to mourners, fishing in the Mediterranean when the borders close, or turning the shells that thankfully didn’t explode into planter boxes. These spiritual acts tether us to our ancestors and each other, even when the land itself is under siege. Land is the way we hold space for grief and joy in the same breath, how we feed strangers like family, and why Gazan orphans never seem to go unaccompanied for long.

Meanwhile, the “civilized” ones, residents of the only democracy in the Middle East, desecrate the land, unearth cemeteries, block aid trucks, bomb seed banks, build forests over depopulated Palestinian villages under the banner of environmentalism, level civil administration offices that house birth certificates, marriage records, death records, and anything that preserves who we are. And yet, we’re uncivil to resist this disrespect of our land.

Who gets to define civility? The ones who bulldoze memory, or the ones who preserve it with every tree, animal, ritual? Is fighting for survival really that uncivil?

I took a class taught by Jewish Voices for Peace on the history of Zionism and Palestine. I was curious what “the other side” is taught. I learned that kibbutzes, often romanticized as these egalitarian beacons of progress, were strategically placed to claim land and erase Palestinian life as part of the broader Zionist project. They were built on ethnically cleansed Palestinian villages, and excluded Palestinians from membership. How egalitarian.

Hadn’t Gretchen lived on a kibbutz? Didn’t she understand our side too? Did I have to take back her gold star?

https://x.com/NourNaim88/status/1770757556102631890

Have you ever seen Wet Hot American Summer? I worked at a summer camp just like that. How American, right? Every five years we have a staff reunion that has basically the same vibe as a bunch of college burnouts wearing letterman jackets back at a high school party.

We’re a couple glasses of wine in at the reunion and I mention to Victoria an old fling of mine still looked good even though things had always felt a bit weird.

She waited until I ran off to dinner to make her move on him and disappear with him for hours. When she returned and announced her conquest with that trademark aloof look on her face, it was like every molecule of air in the forest evaporated.

The betrayal was not that she hooked up with a guy I had a fling with 15 years ago, or was shady and deceitful, or that she thought I’d get upset so she just did it anyway. It wasn’t the declaration that she’s “prioritizing partnership” (“over friends like you” was implied) or other greatest hits from pop psychology like “boundaries” or “healing” or “repair” that tell me that I’m the uncivilized one who’s just not psychologically advanced enough to see things the right way and forgive her and move on. It had nothing to do with the guy. It’s that whenever someone like her sees an opening, whenever she thinks something will benefit her, whenever there’s something she wants, no matter who else would want it or have a reasonable claim to it or be upset by her taking it, she takes it. People like her take everything.

Within a week of speaking up in the group chat, I attended my first protest for Palestine. I also posted an Instagram story about Palestine, which was both the first Instagram story I ever posted and the first time I spoke up publicly about Palestine.

My thought was, if I’ve grown up with these people, if I’ve infiltrated white society so successfully, if they’ve eaten at my parents’ house and know we’re civilized, I might be able to humanize Palestinians with my posts. It’s the least I could do to sacrifice my social standing while my family is getting killed in Gaza and the West Bank. I thought if they cared about me and my family, they’d care about what my people are going through. If rich white girls in California were getting massacred, I’d care. I’d seek to understand why, and I’d stand up for them. I’ve shared resources, offered to educate, suggested organizations to support. Only a short list of people has taken me up on it. Gretchen even reached out asking where to donate, 672 days later.

I wonder sometimes if what I’m doing is too little too late. I hid my heritage, sure, but the terms of my friendships and the way I moved through the world, the agreement that I signed, was based on someone else who fit into the system I was born into. The exotic, generous one from a different culture, the one that was in on the joke. The civilized Palestinian, not the terrorist.

You can’t possibly be racist if you have a Palestinian friend who hands out gold stars, right?

I had betrayed myself for so long, buried and neglected where I came from, and for what? To fit in? Did I even want to be friends with these people, who treat my emotional and spiritual territory as a space of conquest, extracting my natural energetic resources?

Sometimes it feels as though I’m the first person in history to market the technology sold to the military that’s killing her family and wiping her ancestry off the earth.

“To be frank, I find it incomprehensible. I have trouble understanding how it is possible to treat human beings in this way, to treat children in this way, to treat elderly people in this way. It is literally beyond my comprehension — save that, as with so much of the work that I do in cases about mass atrocity, it’s always about dehumanization: They’re not like us. They’re different. And therefore, we are free to treat them in this way.”

—Phillippe Sands, genocide scholar, The Ezra Klein Show, August 2025

I don’t think my maternal uncle would appreciate it very much if I told the story of his life as “the American Dream.” His two children have decisively Arabic names, and grew up going to protests, attending Arabic film festivals, and spending time with my uncle’s Palestinian friends. He is so proud of Palestine and being Palestinian.

My mom didn’t want us to get bullied like she did, so she was more focused on assimilating us. I haven’t been back to Palestine since I was two, and my brothers and I all have American names.

Their family name, Abudayyeh, means “father of the village.” Abudayyehs are teachers, leaders, representing sincerity, peace, generosity. My uncle has always been that for me, whether I actively knew it or not, even more so now.

My uncle never really talked to us about his experience in Palestine. I heard broad stories about when he left and that he might have been arrested, but the rest was kept fuzzy. I’m not sure if he was quiet about it when I was younger because he was trying to protect me, or if he thought I wasn’t ready, or if he thought I didn’t care. I remember thinking maybe he was too one-sided.

Over the past two years I’ve talked more about Palestine to him, about the questions that have come up with friendships, about what I’ve learned about Jews and the history of Zionism, about the moral vertigo of working at Microsoft. He’s opened up to me more, too.

He told me recently that he started organizing and protesting from the basement of his school. Pamphlets and essays are considered free speech in the West, but in the occupied West Bank they were enough to land him in jail. He was kidnapped and jailed four times, with the violence ratcheting up each time, to the point where his father forced him to leave Palestine and the land to which he was giving his life. They never spoke after that. And yet, he’s one of the happiest, most loving people I know.

I sometimes think about what he thought of my apathy, my inaction, my refusal of being Palestinian growing up in a rich white town, and the patience it must have taken to educate me while I was resisting this education. I also think about how little patience I have for people who are learning about Palestine for the first time, frustrated with their lack of outrage. I should probably have more empathy for them given where I was until a few years ago.

Just like any bi-coastal elite, I’m a big fan of The Cut. In February 2025, they published an article entitled “Bring Back the Code of Hammurabi.”

Cat Zhang recounts a betrayal that fractured one of her closest friendships. Her friend pursued a romantic relationship with a crush about which Cat had confided, and was trying to get over. What made the situation worse was not just the betrayal, but the performative and evasive way her friend handled it afterward, through vague texts and offers of “dialogue,” rather than straightforward accountability or remorse. First came the betrayal itself, then the exhausting emotional labor expected of her in order to process, forgive, and move on.

Instead of finding catharsis in conversation, Zhang fantasized about a simpler form of justice — the “eye for an eye” style, à la the Code of Hammurabi. She laments that in modern friendships, the onus of repair too often falls on the injured party, but often this is a way to dodge real consequences and accountabilities.

My friend asked me if I had written it under the name Cat Zhang.

My parents did everything to move us to a nice neighborhood and give us a shot at a future that was better than theirs. Sometimes I think how strange it is to reach this peak, to take an even bigger bite of the American Dream, and not want any of it. I don’t want this world where countries, friends, and jobs take and take and take.

https://x.com/mohammedIhysse/status/1846494787559432206

Sometimes I can’t figure out if I’m the crazy one or if everyone else is crazy. This world is designed so that those on top, stay on top. I live in a system that’s built on a different spirituality: on rugged individualism; polite, civil interactions; kill them before they kill you.

I feel like I’m watching a different movie than everyone else. Part of me wants vindication, part of me wants annihilation, and part of me wants to take a nap. Do things go back to normal? Do I have to rebuild everything?

It’s been a gift to claim that I’m Palestinian, that I share DNA with people who are persisting, resisting, finding joy wherever they can even as they’re being slaughtered for simply trying to survive. If Gazans can defend their PhDs from a tent, construct makeshift ovens out of mud to feed their neighbors, open tutoring centers in the rubble of what was once a school, plant gardens of vegetables and fruit again after airstrikes, paint and draw and write to preserve our identity and history in the face of erasure, I can resist too.

I’m so honored to be of a people with such strength. I can’t believe I’m made of that, and that I ever felt ashamed to be so. They are a people who keep teaching life, because that’s the right thing to do. They are a people who believe that the truth will eventually reveal itself. I’m not sure how one survives such horror otherwise.

If Gazans move on, I can move on too. If my uncle can give me grace for my apathy, I can give grace to people as they come to fully grasp this horror. I can’t throw everything away. What other world would I live in? What other choice is there than to rebuild, then rebuild again?

I’m the first person whose family achieved the American Dream, integrated into upper class society, and then watched the genocide of their people live-streamed. I’m the first person to recognize the duality of the system that propels you forward and holds you back. We’ve made it this far and I’ll figure it out just like every other first. That’s the only way I know how to change the world.