“The Displaced, the Unwanted” is the introductory essay Viet Thanh Nguyen wrote for the anthology he edited of essays by refugee writers, The Displaced, and appears here by special arrangement with the author.

Viet Thanh Nguyen

I cultivate that feeling of what it was to be a refugee, because a writer is supposed to go where it hurts, and because a writer needs to know what it feels like to be an other. A writer’s work is impossible if he or she cannot conjure up the lives of others, and only through such acts of memory, imagination, and empathy can we grow our capacity to feel for others.

I was once a refugee, although no one would mistake me for being a refugee now. Because of this, I insist on being called a refugee, since the temptation to pretend that I am not a refugee is strong. It would be so much easier to call myself an immigrant, to pass myself off as belonging to a category of migratory humanity that is less controversial, less demanding, and less threatening than the refugee.

I was born a citizen and a human being. At four years of age I became something less than human, at least in the eyes of those who do not think of refugees as being human. The month was March, the year 1975, when the northern communist army captured my hometown of Ban Me Thuot in its final invasion of the Republic of Vietnam, a country that no longer exists except in the imagination of its global refugee diaspora of several million people, a country that most of the world remembers as South Vietnam.

Looking back, I remember nothing of the experience that turned me into a refugee. It begins with my mother making a life-and-death decision on her own. My father was in Saigon, and the lines of communication were cut. I do not remember my mother fleeing our hometown with my ten-year old brother and me, leaving behind our sixteen-year old adopted sister to guard the family property. I do not remember my sister, who my parents would not see again for nearly twenty years, who I would not see again for nearly thirty years.

My brother remembers dead paratroopers hanging from the trees on our route, although I do not. I also do not remember whether I walked the entire 184 kilometers to Nha Trang, or whether my mother carried me, or whether we might have managed to get a ride on the cars, trucks, carts, motorbikes, and bicycles crowding the road. Perhaps she does remember but I never asked about the exodus, or about the tens of thousands of civilian refugees and fleeing soldiers, or the desperate scramble to get on a boat in Nha Trang, or some of the soldiers shooting some of the civilians to clear their way to boats, as I would read later in accounts of this time.

I do not remember finding my father in Saigon, or how we waited for another month until the communist army came to the city’s borders, or how we tried to get into the airport, and then into the American embassy, and then finally somehow fought our way through the crowds at the docks to reach a boat, or how my father became separated from us but decided to get on a boat by himself anyway, and how my mother decided the same thing, or how we eventually were reunited on a larger ship. I do remember that we were incredibly fortunate, finding our way out of the country, as so many millions did not, and not losing anyone, as so many thousands did. No one, except my sister.

For most of my life, I did remember soldiers on our boat firing onto a smaller boat full of refugees that was trying to approach. But when I mentioned it to my older brother many years later, he said the shooting never happened.

I do not remember many things, and for all those things I do not remember, I am grateful, because the things I do remember hurt me enough. My memory begins after our stops at a chain of American military bases in the Philippines, Guam, and finally Pennsylvania. To leave the refugee camp in Pennsylvania, the Vietnamese refugees needed American sponsors. One sponsor took my parents, another took my brother, a third took me.

For most of my life, I tried not to remember this moment except to note it in a factual way, as something that happened to us but left no damage, but that is not true. As a writer and a father of a son who is four years old, the same age I was when I became a refugee, I have to remember, or sometimes, imagine, not just what happened, but what was felt. I have to imagine what it was like for a father and a mother to have their children taken away from them. I have to imagine what it was that I experienced, although I do remember being taken by my sponsor to visit my parents and howling at being taken back.

I remember being reunited with my parents after a few months and the snow and the cold and my mother disappearing from our lives for a period of time I cannot recall and for reasons I could not understand, and knowing vaguely that it had something to do with the trauma of losing her country, her family, her property, her security, maybe her self. In remembering this I know that I am also foreshadowing the worst of what the future would hold, of what would happen to her in the decades to come. Despite her short absence, or maybe her long one, I remember enjoying life in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, because children can enjoy things that adults cannot so long as they can play, and I remember a sofa sitting in our backyard and neighborhood children stealing our Halloween candy and my enraged brother taking me home before venturing out by himself to recover what had been taken from us.

I remember moving to San Jose, California, in 1978 and my parents opening the second Vietnamese grocery store in the city and I remember the phone call on Christmas Eve that my brother took, informing him that my parents had been shot in an armed robbery, and I remember that it was not that bad, just flesh wounds, they were back at work not long after, and I remember that the only people who wanted to open businesses in depressed downtown San Jose were the Vietnamese refugees, and I remember walking down the street from my parents’ store and seeing a sign in a store window that said, “Another American driven out of business by the Vietnamese,” and I remember the gunman who followed us to our home and knocked on our door and pointed a gun in all our faces and how my mother saved us by running past him and out onto the sidewalk, but I do not remember the two policemen shot to death in front of my parents’ store because I had gone away to college by that time and my parents did not want to call and worry me.

I remember all these things because if I did not remember them and write them down then perhaps they would all disappear, as all those Vietnamese businesses have vanished, because after they had helped to revitalize the downtown that no one else cared to invest in, the city of San Jose realized that downtown could be so much better than what it was and forced all those businesses to sell their property and if you visit downtown San Jose today you will see a massive, gleaming, new city hall that symbolizes the wealth of a Silicon Valley that had barely begun to exist in 1978 but you will not see my parents’ store, which was across the street from the new city hall. What you will see instead is a parking lot with a few cars in it because the city thought that the view of an empty parking lot from the windows and foyer of city hall was more attractive than the view of a mom-and-pop Vietnamese grocery store catering to refugees.

As refugees, not just once but twice, having fled from north to south in 1954 when their country was divided, my parents experienced the usual dilemma of anyone classified as an other. The other exists in contradiction, or perhaps in paradox, being either invisible or hypervisible but rarely just visible. Most of the time we do not see the other or see right through them, whoever the other may be to us, since each of us—even if we are seen as others by some—have our own others. When we do see the other, the other is not truly human to us, by very definition of being an other, but is instead a stereotype, a joke, or a horror. In the case of the Vietnamese refugees in America, we embodied the specter of the Asian come to either serve or to threaten.

Invisible and hypervisible, refugees are ignored and forgotten by those who are not refugees until they turn into a menace. Refugees, like all others, are unseen until they are seen everywhere, threatening to overwhelm our borders, invade our cultures, rape our women, threaten our children, destroy our economies. We who do the ignoring and forgetting oftentimes do not perceive it to be violence, because we do not know we do it. But sometimes we deliberately ignore and forget others. When we do, we are surely aware we are inflicting violence, whether that is on the schoolyard as children or at the level of the nation. When those others fight back by demanding to be seen and heard—as refugees sometimes do—they can appear to us like threatening ghosts whose fates we ourselves have caused and denied. No wonder we do not wish to see them.

When I say “we,” I mean even those who were once refugees. There are some former refugees who are comfortable in their invisibility, in the safety of their new citizenship, who look at today’s hypervisible refugees and say, “No more.” These former refugees think they were the good refugees, the special refugees, when in all likelihood they were simply the lucky ones, the refugees whose fates aligned with the politics of the host country. The Vietnamese refugees who came to the United States were lucky in receiving an American charity that was born out of American guilt about the war, and resulted from an American desire to show that a capitalist and democratic country was a much better home than the newly communist country the refugees were fleeing. Cuban refugees of the 1970s and 1980s benefitted from a similar American politics, but Haitian refugees of the time did not. Their blackness hindered them, just as being Muslim hurts many Syrian refugees today as they seek refuge.

From everything I remember and do not remember, I believe in my human kinship to Syrian refugees and to those 65.6 million people that the United Nations classifies as displaced people. Of these, 40.3 million are internally displaced people, forced to move within their own countries. 22.5 million are refugees fleeing unrest in their countries. 2.8 million are asylum seekers. If these 65.6 million people were their own country, their nation would be the 21st largest in the world, smaller than Thailand but bigger than France. And yet they are not their own country. They are instead—to paraphrase the art historian Robert Storr, who was writing about the role that Vietnamese people played in the American mind—the displaced persons of the world’s conscience.

These displaced persons are mostly unwanted where they fled from; unwanted where they are, in refugee camps; and unwanted where they want to go. They have fled under arduous conditions; they have lost friends, family members, homes, and countries; they are detained in refugee camps in often subhuman conditions, with no clear end to the stay and no definitive exit; they are often threatened with deportation to their countries of origin; and they will likely be unremembered, which is where the work of writers becomes important, especially writers who are refugees or have been refugees—if such a distinction can be drawn.

The United Nations says that refugees stop being refugees when they find a new and permanent home. It has been a long time since I have been a refugee in the definition of the United Nations: “someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence.” But I keep my tattered memories of being a refugee close to me. I cultivate that feeling of what it was to be a refugee, because a writer is supposed to go where it hurts, and because a writer needs to know what it feels like to be an other. A writer’s work is impossible if he or she cannot conjure up the lives of others, and only through such acts of memory, imagination, and empathy can we grow our capacity to feel for others.

Many writers, perhaps most writers or even all writers, are people who do not feel completely at home. They are used to being people who are out of place, who are emotionally or psychically or socially displaced to one degree or another, at one time or another. Or perhaps that is just me. But I cannot help but suspect that it is from this displacement that writers come into being, and why so many writers have sympathy and empathy for those who are displaced in one way or another, whether it is the lonely social misfit or whether it is the millions rendered homeless by forces beyond their control. In my case, I remember my displacement so that I can feel for those now displaced. I remember the injustice of displacement so that I can imagine my writing as attempting to perform some justice for those compelled to move.

What is unjust about the lives of refugees, of stateless people, of asylum seekers, of all those who are no longer at home? When it comes to justice, it does not matter whether those in a host country think they have no obligation to refugees. Keeping people in a refugee camp is punishing people who have committed no crime except trying to save their own lives and the lives of their loved ones. The refugee camp belongs to the same inhuman family as the internment camp, the concentration camp, the death camp. The camp is the place where we keep those who we do not see as fully being human, and if we do not actively seek their death in most cases, we also often do not actively seek to restore many of them to the life that they had before, the life we have ourselves.

We should remember that justice is not the same as law. Many laws say that borders are sacrosanct, and that crossing borders without permission is a crime. Unpermitted migrants are thus criminals and the refugee camp is a kind of prison. But if borders are legal, are they also just? Our notions of borders have shifted over the centuries, just as our notions of justice and humanity have. Today we can usually move freely between cities within a country, even if those cities were once their own entities with their own borders and had fought wars with each other. Now we look back on those times of city-states—if we remember them—and I doubt few of us would want to return to such a condition.

Likewise, we should look at our current condition of national borders and we should imagine a more just world where these borders would be markers of culture and identity, valuable but easily crossed, rather than legal borders designed to keep our national identities rigid and ready for conflict and war, separating us from others. The dissolution of borders is the utopian vision of cosmopolitanism, of global peace and of a global place where no one is displaced, of humanity as a global community that is allowed its cultural differences but not the kind of differences that lead us to exploit, punish, or kill. Making borders permeable, we bring ourselves closer to others, and others closer to us. I find such a prospect exhilarating, but some find this proximity unimaginably terrifying.

If this global community has not been achieved, it is not because it is a wholly utopian fantasy, a nowhere not marked by any boundary. There have been moments in our history—and many times in our writings and our folklores and our theologies—where we have achieved the best of ourselves in our ability to welcome the other, to clothe the stranger, to feed the hungry, to open our homes. This is what we need to remember as we hope and work for a future where borders do not matter, but people do. This is the kind of memory, the memory of our own humanity, and our inhumanity, that writers can offer.

We need stories to give voice to a writer’s vision, but also, possibly, to speak for the voiceless. This yearning to hear the voiceless is a powerful rhetoric but also potentially a dangerous one if it prevents us from doing more than listening to a story or reading a book. Just because we have listened to that story or read that book does not mean that anything has changed for the voiceless. Readers and writers should not deceive themselves that literature changes the world. Literature changes the world of readers and writers, but literature does not change the world until people get out of their chairs, go out in the world, and do something to transform the conditions of which the literature speaks. Otherwise literature will just be a fetish for readers and writers, allowing them to think that they are hearing the voiceless when they are really only hearing the writer’s individual voice.

The problem here is that the people we call voiceless oftentimes are not actually voiceless. Many of the voiceless are actually talking all the time. They are loud, if you get close enough to hear them, if you are capable of listening, if you are aware of what you cannot hear. The problem is that much of the world does not want to hear the voiceless or cannot hear them. True justice is creating a world of social, economic, cultural, and political opportunities that would allow all these voiceless to tell their stories and be heard, rather than be dependent on a writer or a representative of some kind. Without such justice, there will be no end to the waves of the displaced, to the creation of ever more voiceless people, or, more accurately, to the ongoing silencing of millions of voices. True justice will be when we no longer need a voice for the voiceless.

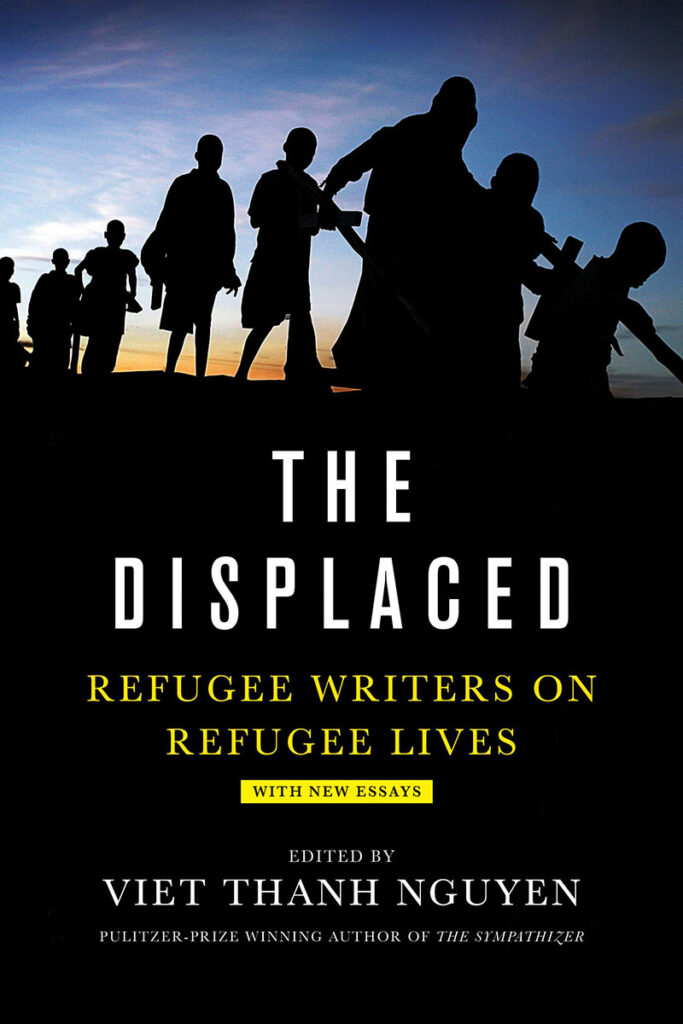

In the meantime, The Displaced collects powerful voices, from writers who were themselves refugees. Joseph Azam, from Afghanistan, speaks of the long process of self-transformation that led to the shaping of his name into a more American fashion. David Bezmozgis, from the Soviet Union, settled in Canada, where he describes practicing quiet solidarity with a new refugee trying to gain permission to stay. Fatima Bhutto, born in Afghanistan to a Pakistani father from an important political lineage, submits herself to a virtual reality version of refugee experiences, and finds herself unexpectedly moved. Thi Bui, who fled the Vietnam War to come to the United States, considers the baggage and fragments of refugee life through sharply-drawn pictures. Ariel Dorfman left Chile and settled in North Carolina, where he spurns the politics of Donald Trump and finds hope in a pan-Latin American supermarket. Lev Golinkin, a Soviet Jewish refugee who winds up in Vienna, describes the quotidian struggle to retain humanity as the refugee experience turns one into a ghost. Reyna Grande, who came to America as an undocumented migrant from Mexico, raises the critical question of definitions—what makes someone a refugee versus a migrant?

Meron Hadero, who came as an infant to Germany from Ethiopia, returns to Germany as an adult in order to reclaim the experiences of displacement and migration that she does not remember. Aleksander Hemon, a Chicagoan from Bosnia, recounts the Candide-like experiences of a fellow Bosnian who had the misfortune to live an epic life. Joseph Kertes, a Jewish refugee from Hungary, describes the unique status of Canada as a country of outsiders, next to but not quite like the United States (in a good way). Porochista Khakpour offers a precise autobiography of her journey from Iran to America, including the precarious status of being Muslim, brown, and American during a time of war. Marina Lewycka, born in a “displaced persons” camp to Ukrainian parents, settled in the UK and to a comfortable English identity—until rising anti-immigrant feeling made her question that identity. Maaza Mengiste, an American writer from Ethiopia, finds herself in an Italian café, watching an afflicted young black migrant through the window, and feeling the pain of her connection to him and so many others forced to move.

Dina Nayeri, born in Iran, raised in America and now a UK resident, challenges the widely held idea that refugees must be grateful by showing how gratitude is a trap. Vu Tran, a Vietnamese refugee who came to Oklahoma, offers a taxonomy of the refugee’s many guises: orphan, actor, ghost. Novuyo Rose Tshuma, whose family left Zimbabwe for a South Africa that was both hospitable and hostile, describes the refugee’s fear of persecution as leading to a desire to be exceptional, and hence acceptable. Kao Kalia Yang, a Hmong refugee whose family came from Laos to Minnesota, dwells on the memory of how the refugee children in her camp struggled and fought to survive.

All of these writers are inevitably drawn to the memories of their own past and their families. To become a refugee is to know, inevitably, that the past is not only marked by the passage of time, but by loss: the loss of loved ones, of countries, of identities, of selves. We want to give voice to all those losses that would otherwise remain unheard except by us and those near and dear to us. In my case, I remember the losses of my parents, and I remember their voices. I remember the voices of all the Vietnamese refugees that I encountered in my youth, hoarse from telling their stories over and over again. But I do not remember my sister’s voice. I do not remember the voices of all the refugees who shared the exodus with me and did not make it, or did not survive.

But I can imagine them, and if I can imagine them, then maybe I can hear them. That is a writer’s dream, that if only we can hear these people that no one else wants to hear, then perhaps we can make you hear them, too.