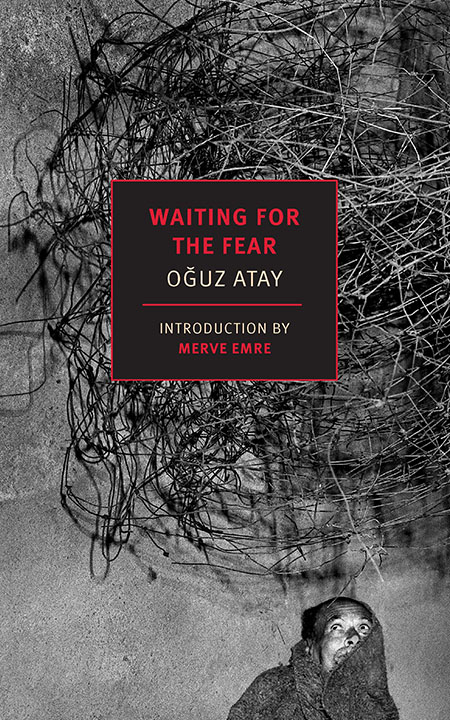

Excerpted from Waiting for the Fear, a volume of collected stories by Oğuz Atay, published by the New York Review of Books, and translated from the Turkish by Ralph Hubbell.

“I’m in the attic, dear!” she called down through the scuttle hole. “Old books are worth a lot of money these days, I wanted to take a look.” Did he hear what I just said? “It’s dark up there; wait, I’ll get you a flashlight.” Good then; it’ll be a calm day. Someone used to tell me that I constantly needed attention. What I need now is a mirror that shows me smiling back; not to mention some light. “You’re going to hurt yourself in the dark.” A hand rose up through the hole, holding a flashlight. The beam strayed towards an empty corner and lit it up. She touched the hand; it disappeared. I wonder what he thinks. She smiled—so, he’s thinking again, is he?

It had been years since she’d climbed into that dusty, spider-ridden darkness. The bugs were already scattering from the light. They scared her, but she was encouraged by the thought that there was something to gain. I shouldn’t have told him what I was doing until I’d finished the job; it isn’t like he’s expecting anything in return. Am I being helpful? I don’t know, sometimes I get confused, especially when I have that humming noise in my head. I wish I knew how to think like him. He’s trying not to let on that he’s watching me, keeping his distance; I’d better hurry.

She pointed the flashlight at something — the portraits of her mother and father; between them an old shoe bag, a few broken lamps. Why had they disliked each other so much? The thought that they would die one day used to terrify me. She picked through the shoe bag. These are the ones I wore with a ballgown to my first dance. Every night, I went out with someone different, just to dance. Good God, how did I manage?

She wiped her dusty hands on the front of her dress. She looked at her purple shoes, creased and spotted with mildew. She slipped the left one on. My size hasn’t changed a bit. She blushed, but she couldn’t bring herself to take it off. She hobbled towards the portraits, knelt down and brought them together. She wiped away the dust with her elbow.

They didn’t understand each other at all — nor me. How I used to cry. Maybe I could find a place for them downstairs, in the hallway or the storage room. I’m being ridiculous; I haven’t forgotten them, I haven’t forgotten them. Her father’s face had a proud, sullen look on it. I couldn’t possibly hang them on the same wall. She closed her eyes, considering the layout of the house. They never liked being near one another; which went for the grave as well. She picked up one of the portraits. The flashlight lay on the floor, so she couldn’t tell which one she held. She perched it up high.

Then she grew flustered, struck her knee on something and fell to the floor—a gentle fall. She didn’t dare get up; instead she crawled over to the flashlight. Another bag. She dumped it out. Old photographs! She was getting sidetracked now. I refuse to let him rush me; even if I have to speak with him later, right now I won’t consider it. She spread out the photographs, passing the light over their dusty figures. I might as well have moved and left all of this to someone I’d never see again. She stirred through them. Good gracious, I liked to have my picture taken.

Most of them had turned out bad. She smiled. The skirts certainly were long and homely back then. And the poses are laughable—the films I must have had in mind! I have my back to the camera, like I’m walking away, but then I suddenly turn my head. Who was I looking at? Here’s another, with that same dress. Someone’s with me. The picture was coated in a film of dust. We still recognize ourselves, even through the dust. She licked her finger, the dust turned to paste and she saw the smiling face of her first husband at the tip of her thumb.

My God, I was married once, and then — and then I got married again. Oh well, you don’t always get there on the first go, do you? How miserable we’d turned out, thanks to those emotions I couldn’t name, let alone describe. She bent over and took a handful of pictures from the floor. I remember, before this one was taken, I’d made a fuss over absolutely nothing and stormed off. And then what happened? Well, here you are, in this house; which is to say that nothing happened with him; nothing bad, nothing good, just nothing at all.

But that’s not how I’d felt; those turning points, they always seem to pivot on the sly. No, you’ve jumbled your thoughts; your simple words — oh, what does that have to do with anything? But then how come I suddenly turned my head as I walked away and made him take this picture? Did I always pose that way? She sat up, brought her hands to her head and began to think. And who knows the look he must have had on his face. I suppose it’s my fault; not when the picture was taken, maybe at that moment I was right, absolutely I was right; but before then, long before.

She wanted to get to the books now, to be finished with this endless journey into the past. She pulled off the old ballroom shoe, but she couldn’t find her soft, closed-back slippers. She shuffled towards the flashlight. The chest of books should have been in the corner, straight ahead. Instead, there were some shadowy protrusions lurking there, and they looked nothing like a storage chest. She pointed the flashlight at the strange pile of clutter, then stepped back in fear—there was someone there, someone sitting. She wanted to turn around and escape down the scuttle hole, but she couldn’t move. Despite her fear, she got closer; her entire life, whatever she did she did in spite of her fear, otherwise she’d have just up and vanished a long time ago.

She held up the flashlight. Oh!—her old boyfriend was lying on the floor. She looked in his face. Like everything else in the attic, he was covered in dust and cobwebs, a statue tied to the chest and the painting easels. His left arm was propped up on the edge of one of them. His fingers curled downward, as if clutching a pen. Her knees shook, her teeth chattered; then she slipped and fell back to the floor, overturning one of the easels with her foot. His arm remained suspended in the air; the spiders had strung it from the rafters. What did he plan to do with that hand? Write something? What a shame, to think I’ll never know. His left hand lay on the floor, holding a gun. Oh, God! I wonder if he’d killed himself. But he couldn’t have! If he’d done such a thing, I would have known, he used to tell me everything. We’d talked about this. He never would have left me all alone.

Then she remembered: one day, after a vicious fight, a day when they both said they’d had enough, he climbed up into the attic. She tried to recall the details. Maybe it hadn’t been such a big argument after all. They could be a little quarrelsome, she supposed. She smiled; he used to hate that phrase, “a little.” She’d left him in the attic and rushed out into the street, pursued by the feeling that she wanted to die. All right, but why? She didn’t know; the only thing that had stayed with her was the violence of her emotions; that was when she saw ‘him,’ in the street.

Even though she was miserable and lightheaded, nursing that death wish, she noted the concern in ‘his’ eyes, noted in them that peculiarity that always seems to sweep one off one’s feet. Of course, she came back alone that day. And there were so many, many more days after that when I returned alone. If he could speak now, he’d tell me that you can’t say ‘so many, many more.’ She pulled herself up to her trembling knees and shined the flashlight in his face; his eyes were open, alive. She couldn’t stare, though, and turned towards the dark.

Then, drawing from the strength that always stayed with her in just such matters of life and death, she looked again. He hasn’t decayed, not one bit. If I hadn’t waited so long to come up, maybe he wouldn’t have turned out like this. The thought saddened her. He hasn’t changed at all; he’s just the same as when I last saw him, even his eyes are open. Except there’s something oddly different about their aliveness; like he knows everything but he’s completely unaffected by it. It used to frighten me, the way he’d say, Never mind how I look, I’m already dead inside. I never believed him.

For someone who was dead inside, he could come up with the strangest things. Maybe he’s watching. She moved. I’d been hard on him, telling him that he didn’t pay enough attention to me. No, he isn’t looking at me; but I’m sure he’s thinking. He used to just suddenly start speaking. When do you get the chance to think this stuff up? I used to ask him; I can’t tell. No, he isn’t really dead; if he was, I couldn’t have gone on living. He knew that.

But how was I to know you felt that close to me? I’d told you that if I at least knew you were all right, I could get along. You could do what you like, I said, it was enough to know that you were alive. I’d said this long before that fight, but he knew our rows never changed anything. For a while I didn’t want to see him, even though I knew he was in the attic; I couldn’t get up there, but he was constantly on my mind. Why hadn’t I called to him? I suppose I just never had the chance; something always came up. And he probably didn’t come down because of the strange voices and noises he must have kept hearing.

Then again, he knew that nothing could come between us; we’d talked about these things. Maybe it was me waiting for him. At first, I wondered if he was staying there just to upset me. Then, later—well, I just never managed to get up there. People were always com- ing and going, and there were the money problems, the meals to cook, the dishes to wash, the house-cleaning, and my having to look after him (he was like a child, he couldn’t even take care of himself); then my parents passed away, and there was the fuss of this and that, and all the other respon- sibilities began to pile up.

Eventually, I just forgot that he was there. (I hadn’t forgotten him, of course). Oh, what can I say, there were far unhappier people in my life to deal with. I didn’t think that he’d stay in the attic that long. I figured that he’d found his way out at some point, maybe when I wasn’t home. Yes, that’s exactly what I thought, what else? He had to be in existence, at any given moment, in order for me to live. If I’d felt otherwise, I’d be dead by now. But how many times had I thought about going up to the attic? If I’d heard him trying to kill himself, I obviously would have; and I’d have paid no mind to all our old resentfulness.

Or maybe I had heard. I do remember there being a bang upstairs at some point; I thought it was the wind slamming a door. How could that be, though? The noise came a few days after he’d gone up into the attic, and there I was, in the corner hugging my knees. I didn’t go anywhere; which means it must have been a gunshot. But then, his heart—trembling, she leaned over. I’ll check his heart. The left side of his jacket had deteriorated; part of it fell off at the touch of her hand; a swarm of cockroaches scattered over his body.

I never paid any attention to his appearance; I never looked after his clothes either; the cockroaches probably got at him through some tear I hadn’t stitched and started eating away. After a while, the hole would have grown. She thumbed his shirt. At least they hadn’t gone for his underclothes. His skin looked like it always had. It isn’t warm, but his heart must still be there. She touched his chest. It’s there, I knew it would be; because otherwise I would’ve died. (I shouldn’t have started my sentence with ‘because;’ now he’ll get angry; that’s right, I lived every moment looking in his eyes and wonder- ing what he’d say.)

He hadn’t decomposed at all. Good, now how can I convince him that I’d never abandoned him, that I had been thinking of him, that I’d only appeared to have forgotten? He wouldn’t understand; he was obsessed with how things looked. He’d think that because I’d met some- one else and begun a new relationship, I’d forgotten it all. But I remember everything, down to this suit he wore the day he went up into the attic. She passed the flashlight over his corpse; the cobwebs gave it a hazy look. Only here, where I brushed away the cobwebs and touched his heart, is it a little dark; like a still from a dream. We’d never had our picture taken together. Like so many other things, we couldn’t even manage to do that.

All that rushing, the constant hassle; what were we running for, what was our hurry? No sooner had we finished one thing than we started another, until the day he went up into the attic; we never stopped, never retraced our steps. And then I was crouched up in the corner for days on end. I didn’t eat, didn’t think; I just smoked. The rooms all fell into disarray, like there’d been a war, and the house practically became uninhabitable. I always liked having a kind of order in my life, but I wallowed in the dirt and filth. I suppose I was punishing myself, I suppose running out into the street and seeing him was nothing more than a wish to fall into a fatal kind of despair. It doesn’t matter. I’m probably saying these terrible things only because you might want to hear them. But I never thought you’d kill yourself, let alone die. I’d always imagined that you were far away, leading an at least apparently quiet life.

She began to calm down, following a cockroach with her light. It was trying to climb over the cobwebs; she worried that its feet would tear his suit apart. God knows how many years had gone by, it probably couldn’t withstand the slightest touch. The bug made its way up his neck and teetered along his cheek. His beard had grown; he never did like having to shave every day. Then, around his temple, the cockroach disappeared. If I hold the light there? She couldn’t; she was too scared. But now, in the half-dark, she saw the bullet hole the ugly creature had crawled into. She shuddered, and as she stepped back the cockroach reappeared, carrying something small and withered in its mouth. Terrified, she shined the flashlight through the hole. The beams caromed about the inner walls of his skull. Oh! The bugs had eaten at his brain, had fed off his softest part — and this one must be carrying away the last of it. She lurched towards him. “Did they really leave you so alone, my love?” she said. From downstairs, she heard her husband’s voice, through that other hole:

“Did you say something, honey?”

“Nothing,” she answered, and plunged her hand into the chest of books. “I was just talking to myself.”