Marian Janssen, a Dutch writer, was asked to write the—unauthorized–biography of poet, essayist and author Carolyn Kizer (1923-2014). Kizer founded the journal Poetry Northwest, became the first Literature Director at the NEA, and a member of the Academy of American Poets— from which she soon resigned in protest because it remained a white old boys club. Her life resembled a soap opera: she had an affair with Abe Fortas, Supreme Court Justice and fixer for President Johnson, as well as with Hubert Humphrey. And when she went to Pakistan in 1964, she returned not only with translations from Urdu, but also with a lover. Most of her affairs were with writers, from Hayden Carruth to Robert Conquest, David Wagoner and John Wain.

Marian Janssen

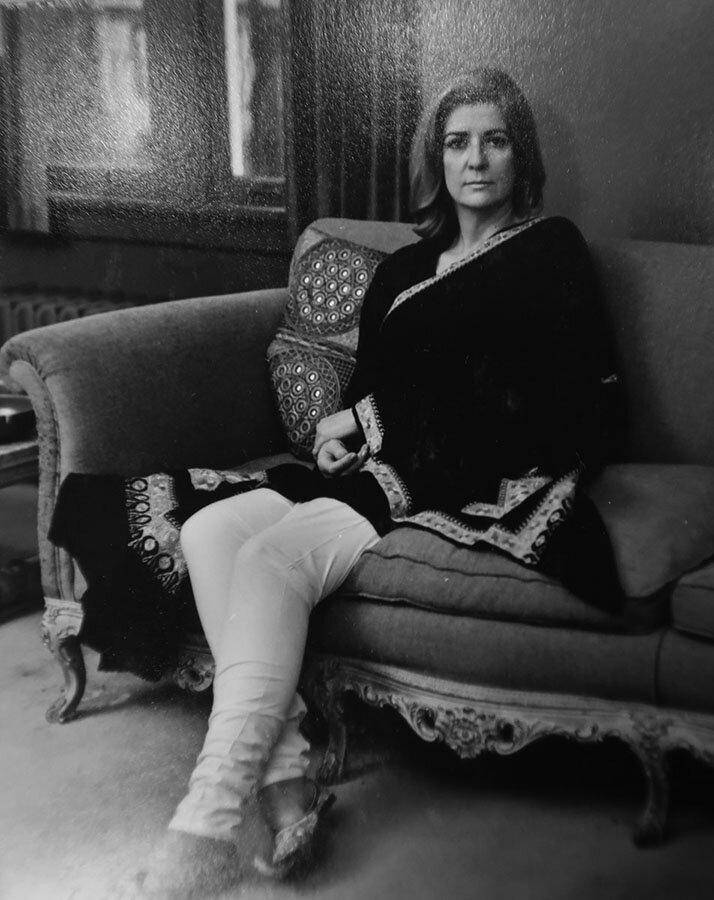

Trying to convince me to write the biography of Pulitzer Prize-winning feminist poet and writer Carolyn Kizer, her daughter, Ashley Bullitt, described her mother’s life as follows: “…a movie-star gorgeous 6-foot-tall Amazon sex goddess who fought . . . her way out of hicktown to go everywhere and know everyone, and was also the wittiest woman in the world, and a brilliant intellectual, teacher and poet, who through her work as a civil servant transformed the role of culture in the lives of the American people.”

Clearly, I could not pass up the opportunity to write about such a female powerhouse and I am now Carolyn Kizer’s biographer. Below is part of her story.

Desperately Leaving Seattle

“Well, it’s happened: I’m free, beige and thirty-eight! I get $5,000 ‘severance pay’ on the first of January, and that’s it. The children are, however, well-provided for, for the first time. And they are hilarious at the thought of freedom: we’re all released from the court order requiring us to live within the Seattle city limits. So onwards with the Guggenheim. And lay it on thick, will you?” (Unless otherwise indicated, quotations are from the Carolyn Kizer Collection at the Lilly Library, Indiana University. This letter is from Carolyn Kizer to Stanley and Elise Kunitz, October 21, 1963. Kunitz Collection, Princeton University.)

Carolyn Kizer, poet and founding editor of Poetry Northwest, was desperate to leave Seattle after the debacle of her marriage to Stimson Bullitt, heir to the King Broadcasting Company media conglomerate, founded by his mother Dorothy in 1946. In October 1963, just a few days after her divorce decree modification came through, she had asked Stanley Kunitz to be one of her referees for a Guggenheim grant. Kizer was lonely in small-town Seattle without her circle of literary friends. Theodore Roethke, her beloved bearlike mentor, had drowned in a swimming pool and David Wagoner, her former suitor of seven years, no longer wanted to see her now that he was married. James Wright and Richard Hugo had left the city. She planned to use the Guggenheim to work on her translations of Tang Dynasty master poet Tu Fu with scholars of Chinese at Columbia University in New York City for half a year, followed by a similar period in Italy, to perfect them. Kunitz’s glowing reference notwithstanding, the Guggenheim went to one of Kizer’s many lovers, editor and essayist Emile Capouya.

In spite of everything she contemplated, from moving to New York City to emigrating to Great Britain, Kizer remained stuck in Seattle almost a year after she had regained her independence. Robie Macauley—then editor of the prestigious Kenyon Review, soon bought out by Playboy magazine—was Kizer’s savior. The State Department had asked him to attend a literary conference in Pakistan, but as he was too busy, he suggested Kizer, who jumped at this chance. Within weeks of her acceptance, State improved their offer, proposing as an experiment that Kizer become their Specialist in Literature—in effect, poet-in-residence—staying for six months (with a possible extension of three) at the royal salary of $700 a month, some $6,000 today. Kizer was hysterical with joy. She could leave small-minded Seattle behind; besides, it released her once and for all from her sadomasochistic relationship with Capouya, “a brilliant, gifted man, but . . . crazier than a bedbug.”

She quickly turned her life around. “She left in a whirlwind, preparing the next double issue of Poetry Northwest with one hand and packing with the other,” co-editor William Matchett apologized to David Sandberg, who wondered what had happened to his submissions. (October 7, 1964. Poetry Northwest Collection, University of Washington, Seattle.) Kizer discussed Poetry Northwest’s editorship with substitute John Logan in Chicago, was briefed by the State Department in Washington D.C., and met with President Johnson’s fixer, brilliant lawyer Abe Fortas—with whom she had had a long affair while still married to Stimson Bullitt. Then on to New York City, London and Paris, ending up in Switzerland (her daughter Ashley accompanied her because she had enrolled at the posh international school Monta Rosa in Montreux), before flying on to Karachi.

Arriving in Pakistan

“Pakistan, Land of Contrasts!” Kizer wrote to her friends just two weeks after her arrival. Although she was generally far more liberal than her fellow Americans, her letter nevertheless shows that she was heavily influenced by the prejudices of her time. “Somehow, I find myself thinking in captions, rather like a tourist brochure or a travel-talk. Behind the hotel, a large old camel tethered to a large new Buick; two boys on one bicycle, the one not pedalling [sic] furiously is leading a young colt; drinking coke on the beach and putting down the Herald Tribune to watch a snake-charmer or a pair of trained monkeys. . . listening to a poet’s young sister chanting a poem in Urdu while a hi-fi set plays a Mozart sonata.” Tongue-in-cheek, she added that she wanted to get her impressions down while she was still “an expert on the country: after a few months I won’t know anything.” She knew that she had come into contact with only a minute number of well-educated and well-off people in Pakistan, but could not praise the women highly enough. She was sure that once they succeeded in breaking free of the restrictions placed on them in even the most enlightened households, they would “light up Chicago on a Saturday night,” because they possessed so much personal electricity. She was enamored, too, of Pakistan’s architecture, its “opulence and wide arms, mak[ing] European gothic seem crammed, overly-vertical and somehow pursed and puritanical.” Lahore, where she lived, was “Metro-Goldwyn-Moghul, tacky, tatty, crumbling pastel plaster, HUGE signs stuck on everything. . . but all it needs is a sign-remover and some buckets of plaster, and the shot-gun marriage of Mohammed and Queen Victoria would be revealed in all its charming splendor.”

Kizer was critical of the men, who were far too interested in playing political games, she judged. She did not take into account that then still-recent Partition of India in 1947, with its heritage of death and destitution, had left bloody wounds. She reserved her most severe censure for Islam. Naively, again, she believed that Pakistan should have done everything in its power to play down religious fanaticism after the mass murders, looting, and raping that had taken place at the time of Partition. Always quick to pass judgment, Kizer condemned what she saw as “a fantastic amount of hypocrisy: Muslims don’t touch alcohol (you should see them lapping up American whiskey at private parties); official standards of chastity and morality are so high that rape is the commonest crime here, and no woman, brown, white, or puce, would think of going alone in the streets after twilight.”

Another dangerous tendency, she concluded, was censorship. The country’s most prominent paper, the Pakistan Times, was a mere instrument of government propaganda, filled with worshipful pages about the superiority of Islam. As a writer, she balked “at the spectacle of slaughter and rapine committed on the English language in every periodical.” As a citizen of imperialist America, Kizer regarded English “in the mainstream of world literature and technical thought,” as the language in which Asia could and should communicate with the world. She also took Pakistanis to task for pronouncing English in such a strange way that “one can listen to quite a long statement before realizing that it is in English, not in Urdu or one of the dialects.” Eventually Kizer stopped her snap judgments and bitching, seeing that her usual “eternal note of asperity” had crept in, admitting that she would probably “blush, should I read it six months hence.”

Poet in Pakistan

As Specialist in Literature, Kizer intended both to acquaint her host country with literary and intellectual trends in the United States and to learn about Pakistani writing and movements. She was determined to devote one issue of Poetry Northwest to works translated from the local languages Urdu, Pashto, or Bengali. Sponsored by the American Asia Society, she also hoped to publish a separate East-West magazine containing works of writers from both countries.

Lahore is situated in the eastern part of Pakistan, close to Kashmir—the apple of continuing territorial discord after Partition. This city was Pakistan’s old cultural center, similar to Boston, Kizer thought, because it, too, was a self-obsessed, stratified society, closed to strangers. And if its literary community was thriving, it was simultaneously very diffuse, most members being educators, lawyers, civil servants, and doctors, who wrote on the side. They were divided into cliques, spending much of their intellectual energy on infighting. As Kizer was the first state-sponsored writer to stay in Pakistan for an extended period of time, she was thrust into this hornet’s nest without being adequately briefed beforehand. She also had to face the fact that Pakistan’s interest in western literature, which was not all that keen to begin with, was British-oriented.

Her first public appearance was inauspicious.

“I went to the University of Karachi, prepared to deliver a lecture on current trends in American literature. I think I shall quote my introduction, by a young woman professor in the English Department, more or less verbatim: ‘Due no doubt to our British heritage, we Pakistanis believe that Americans have no culture.’ Miss Kizer”—she continued, “gulped a few times, and mentally cast her lecture out of the window.” Instead, she read passages from Anne Bradstreet, Emily Dickinson, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau, “coming at last to the safe harbor in the ample arms of Walt Whitman.” She may have managed to convince a few in that audience that Americans have some culture, but she soon found that intellectually and culturally, America was held in low regard. Indeed, in the early 1960s there were no courses in American literature at any university in Pakistan.

As there had been only a short period between Kizer’s being offered her job and her hasty departure for Pakistan, she had not had time to learn any of its languages. Understandably, this, too, made the local literati look down upon her. How dare this person, who spoke English only, pretend to understand their poetic traditions, which were thousands of years old and vastly superior to those of America? Even worse, she was a mere woman. Before she was selected, there had indeed been vigorous debate on the advisability of sending a woman—a feminist to boot—to a strict Muslim country. Kizer, who hardly ever questioned her own judgment, was convinced that it was imperative to do so, “whether or not they want liberated women to visit the subcontinent, they certainly need them!”

As was her habit in dealing with problems, she brought sex and humor into play: “Any woman talking before an audience at a male college has no worries about holding their attention. Many of them are having their first view of the female leg, and one has to resist the impulse to crouch down so as to meet them on eye level.” Truth to tell, she was distressed to find that “the social and sexual mores of this society are so utterly different from our own that—at least until they become used to the idea of a woman on her own. . .it was simpler to behave as if I didn’t exist.”

Being undervalued and overlooked made her first weeks in Lahore extremely tough on Kizer, who was used to being the center of attention. A serious case of dysentery—though it had the one advantage, she thought, that it made her lose twenty pounds—upset her further. Distraught because the United States Information Service (USIS) left her to flounder, she sent a missive to the highest official she knew, Abe Fortas. He was keen to rush to her rescue: “I hope that you are no longer being neglected. What a stupid waste of great natural resources. When you get this letter, if things are not straightened out, send me a cable . . . and say, ‘Please do something.'”

In the end, his intervention was not necessary, for Kizer had found her way: she had secured a male chaperone, a young and handsome writer, Aijaz Ahmad.

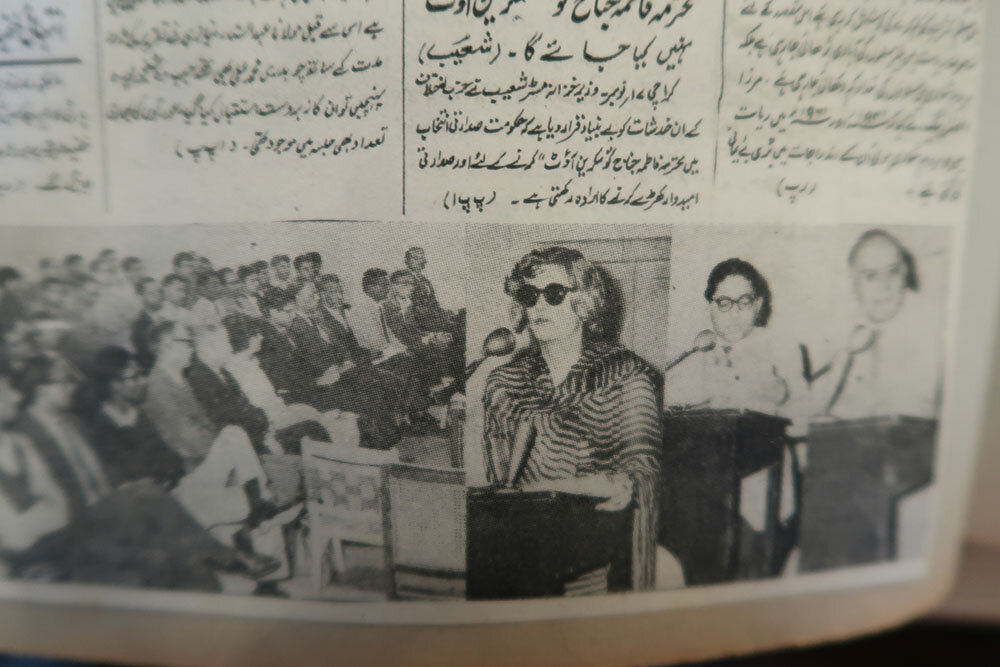

After she had overcome her dysentery, USIS helped organize numerous introductory teas, dinners, receptions, and readings. Often, these gatherings were separate for men and women—the larger ones mainly for men only. In the course of her stay, the invitations came to include visits to sculpture exhibitions, touristy trips to the ancient architectural splendors of Mughal Fort Lahore and the paradisiacal Shalamar Gardens, as well as to the National Horse and Cattle show. She loved the mushairas—interactive poetry performances where Urdu poetry was spoken or sung—the most. For although Kizer did not understand the language, poetry, for her, was first and foremost musical. USIS also arranged her poetry readings and lectures. While she was initially regarded with suspicion, she soon became a source of fascination. USIS noted with satisfaction that her reading in Lahore attracted its largest audience ever. She even won over the head of the English department of a men’s college, “who was known to feel strongly that Matthew Arnold was the last great poet of the English language,” but who, after hearing her, decided to give a tea in her honor—and asked for more lectures.

Kizer spent much energy on her translation project. At the time, hardly any Pakistani poetry had been translated into English and, according to Kizer’s chaperone, the quality of translations was almost always lamentable. For access to Urdu poetry, Aijaz Ahmad told me in an interview, “she relied almost exclusively on me.” Kizer traveled all over the country, delighting in the fact that every little town had its own poetry club, Pakistan being “one of those places where you may be barefoot and penniless, but you know a lot of poetry and you can recite it by heart.” Because she spoke nothing but English, it was impossible for her to pinpoint poems worthy of translation, the more so because most Pakistani poets recommended their friends’ work and were offended if Kizer met their rivals. They were happy that, thanks to Kizer, their work was finally attracting international attention, but not sufficiently motivated to translate themselves, even though Kizer had obtained a grant from the Asia Society to pay for such contributions.

Only a very few poets were admired by almost everyone. One was Pakistan’s pet showpiece, the internationally famous and formidable Urdu writer Faiz Ahmad Faiz. The people at USIS were grateful when Kizer contacted him and the two became fast friends. Faiz, who spoke English, helped her translate his work. They were far less pleased, though, when Kizer decided to meet another of Pakistan’s well-known poets, Khan Abdul Ghani Khan, who wrote in Pashto. Ghani Khan had spent much of his life in prison (mostly under British rule) because of his political activism. His government was silencing him and much of his poetry remained unpublished at the time. He was obsessed with art and poetry and not at all interested in leading a tribal uprising; besides, his years in prison, drink and drugs had damaged him. Nevertheless, the American embassy, treading very carefully, feared a diplomatic incident and refused Kizer permission to visit.

Kizer did not care and met Ghani Khan secretly in the beginning of 1965, though not so secretly that the consul did not find out: fearing repercussions, he was furious with her. Ghani Khan and Kizer also became friends and after their meeting he wrote her long, sometimes paranoid letters about his addictions, her cowardly, stupid government, and spineless Americans in general. One of his letters ended on a ray of hope, though: he felt like a poet again, for new poems were “getting ready in my bones.”

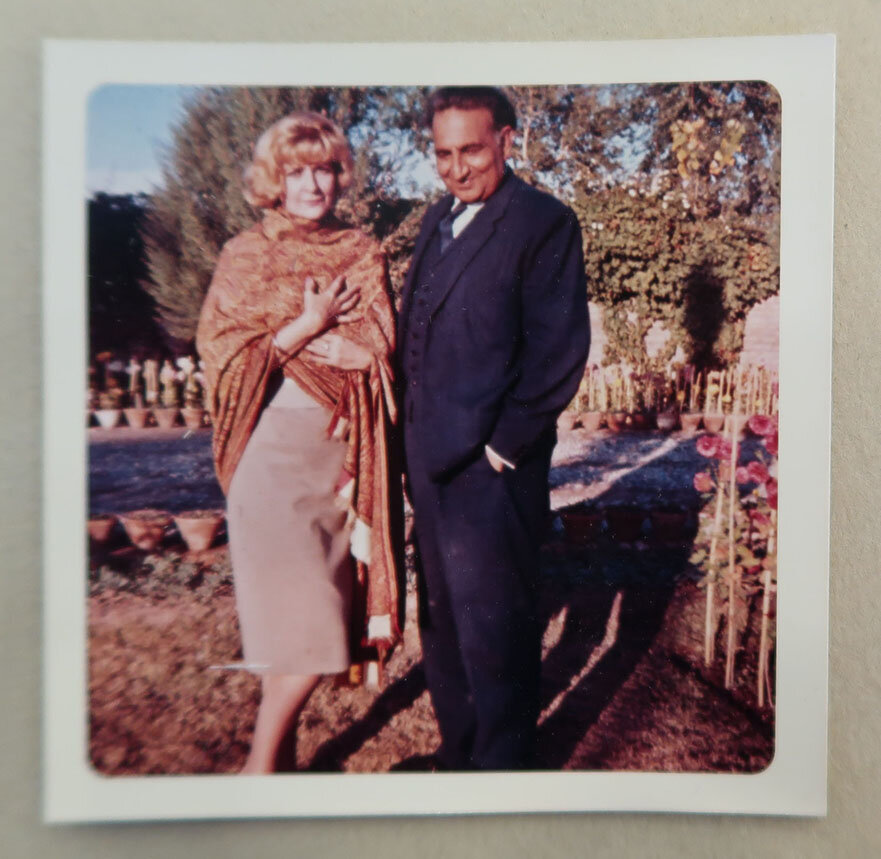

By that time Kizer had her own poet. She had been very lonely during the first few weeks of her stay, for Kizer never could function without a man. She fell for Aijaz Ahmad, who was movie-star handsome, well-educated, and an inveterate reader, almost as soon as she met him. Ahmad was—like many other Pakistani men—fascinated by Kizer. Tall, blonde, and brash, she was the antipode of Pakistani women. “She is a goddess!” a poet exclaimed after attending one of her readings at a mushaira, “She is mighty!” (quoted by Barbara Thompson, “Carolyn Kizer: The Art of Poetry,” Paris Review, Spring 2000.) Kizer’s true interest in their poetry and culture (though prejudiced, she was far less hegemonic than most of her fellow Americans) and her ravishing reading in a rich contralto in a country where the oral tradition was vital endeared her to Pakistani writers, particularly Ahmad. Soon, they had become inseparable, Ahmad transporting her everywhere, usually on the back of his scooter. Kizer needed an escort, for it was unwise to go about unchaperoned anywhere. As it was, she was stared and jeered at, and even beaten with sticks on her bare legs.

Ahmad’s and Kizer’s relationship turned sexual. Theirs seemed like a very unequal alliance, particularly in Pakistan’s cultural context where women were subservient, self-effacing, and soft-spoken—everything Kizer was not. Few Pakistani men would have been able to cope with her, yet Ahmad was. (American men also found it difficult to deal with Kizer’s self-assurance and sense of entitlement, her conviction that she was more brilliant than most of them—as indeed she was.) Furthermore, she was taller than he, something most men would have found threatening to their masculinity. Finally, Ahmad was not yet thirty, while Kizer was in her early forties. Did Kizer regard him as a pretty boy toy to pass the time with? Initially that may have been the case, but their correspondence after Kizer left Pakistan and Ahmad behind reveals that they developed deep feelings for each other.

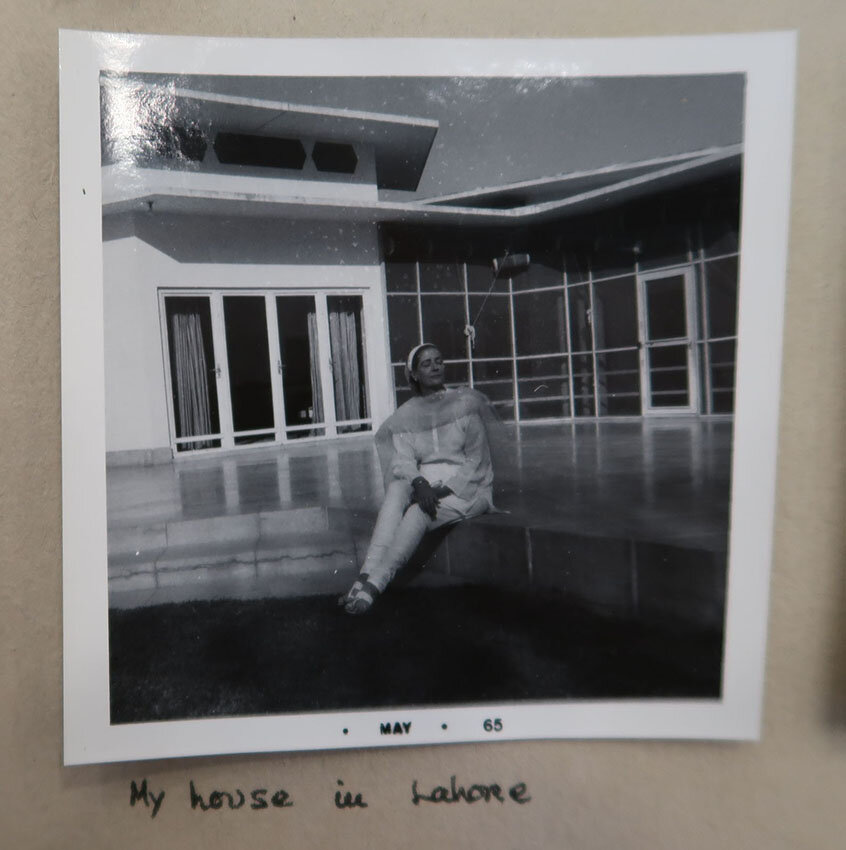

A few months after her arrival, the American consul had decided the house Kizer shared with two Fulbright ladies was simply not good enough for her. He allowed her the use of one of the most luxurious houses in all of Lahore. Its previous, high-placed American inhabitant had been found in flagrante with someone else’s wife and had therefore been sent back to America in shame. Having a whole house to herself opened up myriad possibilities for the burgeoning romance between Kizer and Ahmad, away from both the prying eyes of her former housemates and the local and expat communities in Lahore. Considering the circumstances under which Kizer had been assigned her new home, it is probable that they kept their relationship a secret. USIS would not have been so approving of their first long-term Specialist in Literature, had they known that she was fraternizing with a leftist local poet. Many of Ahmad’s anti-American friends would have looked askance at their liaison, too. When she returned to Seattle, their correspondence was often veiled— Ahmad fearing that his government was spying on him. Nevertheless, his first letter ended: “[t]here will be nothing and nobody in my life whom I may love so much, so fully, with so much tenderness and gratitude—nothing that will make me happier or a better man.” He was sore, though, that Kizer had not taken the three-month extension, which USIS had urged her to accept.

In the spring of 1965, in her debriefing, Kizer explained that she had turned the extension down because of the escalation of the Vietnam war, lecturing State Department officials on how ruinous their Vietnam policy was. (The head of its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs did not mind: he thought she was “the greatest thing since color TV.”) Kizer’s official “Report on Pakistan” shows that her half year in her host country had opened her eyes politically. Before, she had not understood the anti-Americanism of both Pakistan’s intellectual left and its government. All condemned what they saw as America’s naivete in supporting India’s aggression towards Pakistan; all condemned its uncooperative stance in the smoldering Kashmir conflict. America’s imperialist involvement in Vietnam had only aggravated those hostile sentiments. Its coca-colonization as well as, conversely, the “bands of roving Beatniks and assorted intellectual poor white trash . . . searching for thrills from drugs, religious mendicants and sexual exotics” further violated the customs of the host country. (“Report on Pakistan.”)

During her stay, however, Kizer’s opinion of Pakistani women had changed for the worse. In her final report she described them as “extremely dull,” because, she stated, they were undereducated and underexposed—but then, to her, most American housewives were not worthy of attention, either. As she had predicted in that first long letter home, she now realized that it was hard to evaluate the qualities of Pakistani culture, because it was in such contrast to her own. Not surprisingly, then, her advice to the State Department was to send more long-term specialists. Their main task should not be to try and impose American values (standard USIS policy), but instead, “to become familiar with Pakistani culture, to sympathize, to identify, to appreciate” and (like the Russians, she goaded) to give aid in the preservation of their culture.

Though some of Kizer’s remarks in her fifteen-page official report were patronizing, in all, she was at least as critical of her own country. Yet, USIS lauded her imaginative and practical ideas for cultural programming. “She personally could reach an audience which is, in general, politically alienated from the U.S. at this time,” USIS noted. “She is a dynamic, stimulating person, an extremely outspoken and articulate woman,” they praised. “Being a woman and without a knowledge of Urdu she would have been submerged here without some of her forcefulness and a marvelous sense of humor.” They also remarked that her contacts were far more meaningful than those of the usual three-day visiting specialists, surprisingly mentioning that her presence had been of particular encouragement to women writers.

Kizer did not correspond with, publish, or translate Pakistani women after her return.

Back in the U.S.A.

“When you were here,” Ahmad reminisced a few weeks after she had left, “we rarely talked of anything other than poetry, or criticism of poetry. That was mainly because I wanted to be worthy of what interested you.” He hoped she would either return to Pakistan soon, or that he could come to America. From the Kizer Collection at the Lilly Library, it is apparent that Kizer did her utmost to find a Fulbright or a position for Ahmad (“the most brilliant young man that I met in the course of my stay”), while he was usually too depressed to undertake any action himself, preferring that Kizer return to Pakistan. But she had left just in time: the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965 broke out soon after her departure. Cities were bombed and American women and children evacuated. Fiercely patriotic, in the midst of death and destruction, feeling he was writing in a vacuum as mail came through only very intermittently, Ahmad gave up on Kizer. He was sure he would never see her again.

Kizer, meanwhile, increased her campaign to have Ahmad come to America. She even wrote Senator Fulbright personally, emphasizing that the State Department might be cut out for putting “together programs for farmers and scientists (watching chickens or cyclotrons),” but should not have a say with respect to programs for cultural appointees. One of her examples was of a reporter from the Pakistan Times, “who wandered lonely as a rather dark-complexioned rain cloud, getting himself turned away from, or thrown out of, Southern whites-only restaurants by irate proprietors.” Obviously, she commented, his ordeal made splendid copy in the Pakistani anti-American papers, thus entirely defeating the purpose of the Fulbright program.

There are gaps in the—one-sided—correspondence at the Lilly Library and I am not sure whether Kizer’s personal appeal helped Ahmad gain entry to the United States. They were reunited in November 1966, about a year and a half after they had last seen each other. By that time, Kizer’s career had taken off spectacularly. President Johnson had created the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and its first director had made her director of its literary program—with a nepotistic nudge from Abe Fortas. Self-styled “cultural czarina,” Kizer found herself shadowed by the FBI. From the hundreds of (often partially blacked out) pages of the Bureau’s reports it is clear that Kizer—anti Vietnam, a left-liberal suspected of communist tendencies—underwent a full field investigation. Not only were her college classmates interviewed, but also various landlords, as well as her Seattle neighbors. One of those complained that Kizer “had spent a good deal of time during warmer weather sitting or working in her front yard scantily clad” which was “improper and illustrated [her] unstableness.” Indeed, not only Kizer’s allegiance to the United States, but her career, character, and love-life all underwent serious scrutiny. FBI’s final, bureaucratese verdict was affirmative, however: “She is considered loyal to United States although non-conformist.” Confident of a positive outcome, and eager as always to flee from Seattle, Kizer had already moved mid-term to Washington D.C. with her two younger children, Scott and Jill. Ahmad joined them there and came to live in her basement apartment.

Kizer had never made a secret of the fact that she had lovers—her teenage daughter Ashley was her confidante, sometimes even wingwoman—but Scott and Jill did not seem to realize that the relationship between their mother and Ahmad was more than that of mentor and mentee, lessor and lessee. Kizer introduced him everywhere, taking him to parties where they hobnobbed with Washington luminaries such as Bobby and Teddy Kennedy (according to Kizer “a ferret” and “gorgeous,” respectively), but also, often, with Washington’s “colored” establishment. Ahmad never held back his impassioned political views. When, at a dinner party, prominent black journalist Chuck Stone, decrying the continuing discrimination of Blacks and wondering where people of color were ever “going to get the TROOPS to fight the Whites,” Ahmad answered: “Asia, of course, buddy. We have plenty of dark Asians who will fight on your side.” Kizer observed that she was glad he was not talking with activist Rap Brown (now Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, imprisoned for murder), otherwise the two of them would have marched on Georgetown right then and there.

Their political differences were small, however, Kizer being just slightly less vocal than Ahmad. For though she was now working for the Johnson administration, she remained outspoken in her opposition to his war in Vietnam. But in America the contrasts between their two utterly different cultures were magnified. Dependent on queen bee Kizer, in her country, in her social circle, Ahmad, a landowner used to being served, accustomed to deference, was humiliated. Living in her basement did not help. Kizer prided herself on giving him a footing among the intelligentsia, on supplying him with books, paintings, and even clothes. She stamped him all over with her American way of life. Her well-intentioned generosity (if with a paternalistic whiff), proved too much for his sense of self-worth. For some two years, though, they managed to make both worlds meet. They worked together on translating Urdu poetry, introducing its now so beloved ghazal to America. “If I Were Certain,” one of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s ghazals which they had (freely) translated together was particularly pertinent. It ends:

No song of mine can be a panacea

For suffering, though it may soothe your grief.

My song is not a lancet but a salve

Touching the famous sorrows of your life.

Only a knife can end your agony,

Killing, redeeming. I cannot fulfill you.

Nor any breathing being on this earth

Except yourself, except yourself, except yourself.

The Nation, November 4, 1968

Coming to America: The Ghazal

As early as March 1965, Kizer had written poet Hayden Carruth that she was working on ghazals with help from native translators. She was enchanted by the ghazal’s formal restrictions, especially the second line, which “always ends with the same word, usually with the same phrase; and sometimes the whole line is repeated, preferably with the same slight twist which you give a repeated line in a villanelle. The fun comes in deciding on the refrain line” (Carolyn Kizer to Hayden Carruth, March 12, 1965. Hayden Carruth Papers, University of Vermont). She also was busy working on her special Poetry Northwest issue on Pakistan. In the end, she published an international issue with poems by three Pakistani poets—Zulfikar Ghose, Shahid Hosain, and Salim-Ur-Rahman—squeezed in between translations and impressions from Chinese and Japanese poetry. In her contributor’s notes, Kizer listed optimistically that Salim-Ur-Rahman was “industriously and eloquently translating contemporary Urdu poetry into English for a special issue of this magazine” (Poetry Northwest, 1965-1966, Vol 6,4 p. 48). That was not to be, because Salim-Ur-Rahman, battered by the war, had become not only violently anti-India, but also anti-America—and anti-Kizer: “It is this mass-killing [in Kashmir] which never gets reported in American Press. You don’t care, do you?” he scolded in November 1965. He now was against the idea of a special issue, thinking this a step down from a general one. A few months later, in February, he was no longer in the mood for translating, either, having come to regard it as “troublesome and unrewarding work. No offense intended.” In the end, the East-West magazine for the Asia Society also failed to materialize.

In January 1968, Ahmad and Kizer did perform together on a program for the Asia Society, “when he and I will read Urdu poetry and his and my translations of same. All sorts of prominent people have been invited, so I am anxious that we be a success.” (To Benjamin Kizer, January 19, 1968. Lilly.) Indeed, Kizer had not only written to numerous people on Ahmad’s behalf, trying to find him a graduate program, a teaching assistantship, or a job as a translator, but had also introduced him to her enormous network of literary friends. Ahmad’s brilliance, drive, and his love for his native poetry resonated with a number of poets—among them William Stafford, already established and, on the brink of fame, William Merwin and Adrienne Rich. He convinced them to write versions of Ghalib’s timeless ghazals for the centennial of his death. Following the method Kizer and he had worked out together, Ahmad translated and annotated the ghazals, and the American poets then wrote their free “transmissions.” The ghazals’ music, language of loss and love, their otherness, and abstract multivalence rang fresh with poets and a reading public that, at the beginning of the hip 1970s, were looking for an escape from literary modernism and cultural-political isolationism. Ahmad’s Ghazals of Ghalib (Columbia University Press, 1971) is now generally regarded as having introduced ghazals to America, where they almost immediately became embedded in its literary tradition.

The glaring omission in this collection is Kizer.

Opposites attract and after their reunion Ahmad had even mentioned matrimony. However, after her first, prison-like marriage, Kizer cherished her freedom; besides she thought Ahmad deserved starting a family—and she was not willing to burden herself with more children. Clashing cultures, contrasting views of the roles of women and men, in combination with their proud, fiery characters became a recipe for disaster. They broke up at the end of 1968. In her vitriolic farewell letter, Kizer mentioned their sexual incompatibility—managing to emasculate him, Ahmad must have felt, by telling him that she had been totally frustrated. Kizer was embittered that Ahmad had traded her for Adrienne Rich, only a few years younger than her and a similarly unfit candidate to have children with. Kizer herself was two-timing him, too, though, with an Austrian-Australian opera singer and producer, who had the advantage of being married and living abroad. Ahmad, for all his attractive otherness, was part of her daily life, and therefore just too close. Recognizing that Kizer had tried to pave the way for him in America, and still caring for her, Ahmad truly hoped to remain friends, but Kizer excised him from her life.

Kizer’s love for Urdu poetry and the ghazal remained steadfast. While most American poets were following in the footsteps of those published in Ahmad’s collection and played with the ghazal’s rules, Kizer adhered to its original conventions. Kashmiri American Muslim poet Agha Shahid Ali considered the free verse ghazal a contradiction in terms. In September 1996, he implored Kizer to write a real ghazal, as she was “someone who knows forms intuitively.” “Let’s—please—put this thing called ghazal, floating from so many American monthlies to quarterlies, in its proper place, for it is nothing of the kind,” he started his “Transparently Invisible: An Invitation from the Real Ghazal.” “When I complained to Carolyn Kizer (as a translator of Faiz Ahmad Faiz she knows the real thing) that the Americans have got the ghazal quite wrong, she, in extravagant despair, responded: ‘Have they ever'” (Poetry Pilot, Winter 1995-1996, p. 34).

Kizer had translated real ghazals such as “Among the Trees” by Nazir Kazmi with Salim-Ur -Rahman:

Yellow and white and red and blue and green—

No end to color there among the trees.

The sad and lovelorn princess of perfumes,

I apprehended her last night among the trees.

For an interval, so brilliant were her eyes

There was a kind of glow among the trees.

The path of lights ran straight, then suddenly

For some dark reason, swerved into the trees.

The denizens of the garden were amazed

Last night: There was a man among the trees.

Carbon copy, Kizer collection, courtesy Lilly Library

Ali’s anthology Ravishing DisUnities: Real Ghazals in English (2000) caused another explosion of interest in this verse form. Ironically, Kizer never contributed to this dazzling array of over a hundred poets writing real ghazals either. It is understandable, therefore, that her indirect but substantial role in bringing the ghazal to America has been forgotten.

Poets in Pakistan

Kizer’s affair with Aijaz Ahmad can be seen as emblematic of her relationship with his home country. If as an American government emissary in Pakistan, she had been much more appreciative of its culture than most government officials, in the end, she favored her own. But whereas she fell out of love with everyday Ahmad, she continued to romanticize faraway Pakistan. She had ended her report in 1965: “And I know I’ll go back to Pakistan one day, with or without help from Uncle, to see my friends, Pakistani and American, and that crazy mixed-up country that I pity, deplore, and love.”

In the fall of 1969, Uncle Sam asked her to attend a conference in Pakistan. Kizer accepted gladly: “I was a Lahore-wallah, and this feels more like coming home than it would to, say, Seattle, Washington, where I spent fifteen years of my life feeling like a transient,” she noted in “Pakistan Journal,” published in her collection of translations, Carrying Over (1988). “I lived there just long enough to know how little I knew,” she now admitted. Her journal anonymized most of her sources and friends, to protect them in a country that had become even more anti-American than four years earlier. Ghani Khan, already hounded, and Faiz Ahmad Faiz, too famous, perhaps to suffer prosecution, were exceptions. With Faiz she sat at the hotel bar, drinking gin and going over translations. When her fellow-conferencegoers looked for her, the hotel staff refused to tell them her whereabouts. “They damn well weren’t going to interrupt us. They know how to treat poets in this country.”

Thank you for this fascinating and useful account.

It is especially important to bring attention to Kizer’s role in bringing the ghazal to the U.S..!

Please note, however, that the translation of “Among the Trees” is not a “real ghazal” in the sense meant by Agha Shahid Ali, because it omits the kafiya (the rhyme that should precede the repeating phrase). Shahid’s goal was to teach poets in English to use the kafiya; if this ghazal were a “real” one in that sense, the words “there,” “night,” “glow,” “swerved,” and “man” would instead be words that rhyme with each other.

Dear Annie,

I hope you and yours are well. Thank you so much for this positive and very useful comment. I’ll change my remarks on “Among the Trees” in the final version of my manuscript!

Marian