Lebanese Canadian writer and visual artist Joyce Joumaa’s videos demonstrate that the colonized are not passive recipients of their condition.

A soccer match plays on screen between Algeria and France. A man unloads his gun into a soldier. The game continues. A chase begins; French soldiers stop and frisk a senior citizen. Spectators flood the soccer field. The French are unable to control the Algerian crowd. The game comes to an end.

Joyce Joumaa’s Bêtise Humaine (Human Stupidity), previously exhibited at the Jaou Tunis, will be on display at the MOMENTA Biennale d’art contemporain in Montreal, Canada starting September 10, 2025. The video is a split screen of a 2001 French-Algerian soccer game and scenes of Algerian freedom fighters attacking French colonizers in the movie The Battle of Algiers. The match was the first and only one France played against Algeria since the latter gained independence in 1962.

As her site notes, Joyce Joumaa is a Lebanese Canadian visual artist and writer “based between Beirut, Montreal and Amsterdam.” Joumaa’s work focuses on microhistories in the Arab world, as a way to understand how past structures inform the present moment.

The juxtaposition of violent decolonization, whether with guns or on the field, is part of Joumaa’s growing work focusing on the microhistories of conflict and liberation in SWANA and its diaspora. Bêtise Humaine follows up on Memory Contours at the 2024 Venice Biennale, where Joumaa was the youngest artist. Amid the sounds of rain droplets and waves, four pole-mounted screens give close up shots of hands drawing shapes on a piece of paper. There is beauty in the minimalist forms, until we learn it was part of a test administered to immigrants arriving at Ellis Island a hundred years ago, to measure their cognitive abilities. Failure meant deportation.

Resembling sigils in a book of magic, the drawings feel otherworldly. Yet, cognitive fitness is still part of immigration controls today. Having studied art in Canada, Joumaa had to demonstrate that she would not cause “excessive demand on health or social services” before entering. These ableist laws assume that immigrants are coming to steal from “our” medical services. Or maybe they are just reclaiming what is theirs?

Neocolonialism extracts from the Global South, leaving the latter with little to invest in medical infrastructure. Here, migration becomes a form of decolonial reparations.

Returning to Bêtise Humaine, decolonization also means reclaiming the ground, even a soccer field. International sports sells itself on reconciliation and meritocracy, with former enemies mending ties through the game and the best team coming first. But what does it mean when the game is between the colonized and the colonizer?

“Reconciliation” means acceptance of the status quo, not giving back what was stolen. And “meritocracy” means whoever has the most money to hire and train athletes wins. Ironically, the Western states that exclude “unworthy” immigrants also recruit racialized youth to join soccer clubs. The top players are then cheered on by racist football hooligans. Eugenics comes in again: the disabled immigrant must be kept out, while the fit immigrant can come in to promote nationalism.

Frustrated with France’s 4-1 lead, Algerian spectators flood the field 15 minutes before the game’s end, rushing past French security. Simultaneously, the left side of the screen shows Algerian masses storming French soldiers in Algiers. It is not just the demand for decolonization that threatens the French, but the crowd itself. With the city divided between European and Algerian areas, the fear is the Algerian mass could rush the checkpoints and take the city, along with the country.

Unable to control the Algerians, the match is cancelled. While France won the game, Algerians were victorious in rejecting the reconciliatory and meritocratic ideology. But the struggle continues, as the zones of control expand from the apartheid city and soccer field to the border. Today, politicians from the far-right to the center warn that Algerians will take over France, as the parliament bans the niqab, saying it will protect women. In Bêtise Humaine, the soccer announcer suggests that they should have had a fence to keep the spectators out, the same ones found now in Calais.

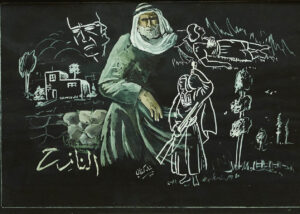

But what France fears is not that Algerians will turn France into a caliphate or force women to cover themselves. The problem is that Algerians remind France of its colonial past and defeat at the hands of the “inferior” Arab. Here we understand the anxiety around the niqab: rather than a symbol of women’s oppression, Algerian women used it to smuggle weapons and supplies during the Algerian War of Independence. We see this in Bêtise Humaine, where a woman in a niqab passes a revolver to the protagonist, Ali la Pointe, before he kills a French soldier. Other scenes from the movie, although not featured in Bêtise Humaine, include women using the niqab to smuggle bombs and men hiding themselves under the niqab before unloading their machine guns into French soldiers.

These scenes are why the Battle of Algiers still resonates for both the colonized and colonizer. Before the invasion of Iraq, the film was shown to the Pentagon, with guests told it would demonstrate “How to win a battle against terrorism and lose the war of ideas.” The film is a favorite of Palestinians, which is why it was initially banned in Israel. The fear was that the simulation of decolonization could provoke real life resistance.

In the 21st century, simulations of resistance have now moved from the film to computers. At the Never One Thing Alone exhibit at Gallery TPW in Toronto, Joumaa’s Untitled is a variation of Bêtise Humaine. This time the 1974 documentary They Do Not Exist is layered over a soccer video game match of Manchester United — one of the most valuable sports clubs in the world — versus Club Deportivo Palestino, a century old Palestinian soccer club in Chile. They Do Not Exist shows daily life in Nabatieh refugee camp, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon; freedom fighters training and condemning imperialism; and Israeli jets bombarding the camp until nothing is left.

The video game shows Manchester scoring goal after goal, with a final score of 6-0. Unlike in real life, the spectators are not going to stop the match. But what video games allow for is repetition, playing over and over again until you win. With enough practice, even a small group of Palestinians can defeat the Western Goliath. As we watch Israel’s genocide of Palestinians in Gaza, we often forget that Palestinian’s continuous struggle has often resulted in victory, including Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000 and from Gaza in 2005.

The title, They Do Not Exist, comes from Former Prime Minister of Israel Golda Meir who said, “There were no such thing as Palestinians… They did not exist.” But as the film shows and as we see a half-century later, Palestinians do exist, whether in refugee camps or on the soccer field. Joumaa’s videos demonstrate that the colonized are not passive recipients of their condition, but actively resist it through migration, guerilla warfare, storming the soccer field or playing against Manchester United in a video game.