Amber Sackett

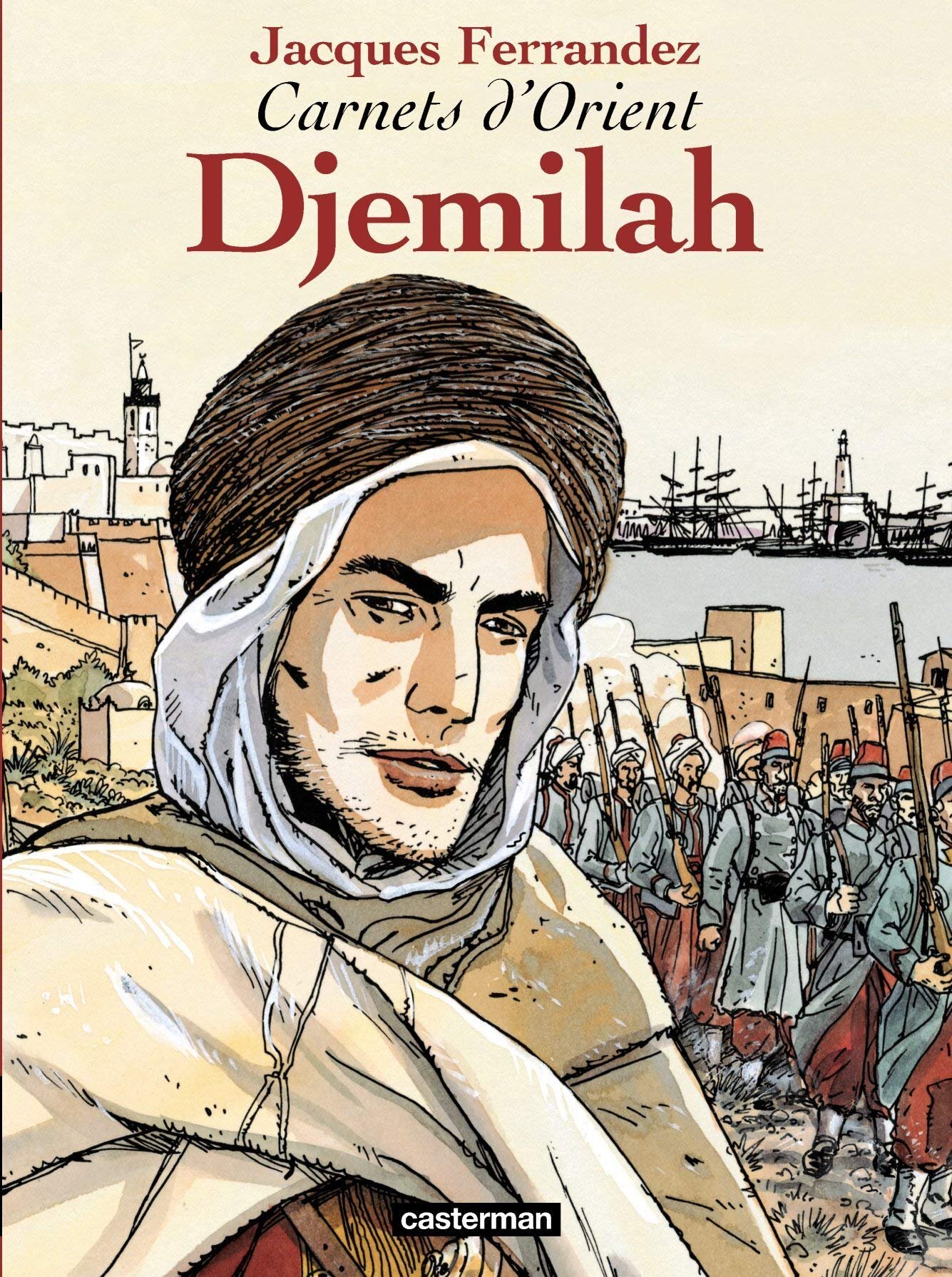

Prior to the 1986 release of Jacques Ferrandez’s popular series Carnets d’Orient, French graphic novels largely avoided the subject of the Algerian War. Published from 1986-2009, Carnets d’Orient consists of 10 volumes spanning a period from the beginning of French occupation in 1836 to the end of the Algerian War of Independence in 1962. Attempting to showcase French colonialism in Algeria through a politically neutral perspective, each work centers around diverse characters from various ethnicities, ages, religious backgrounds, and social class.

Ferrandez’s historical fresco was immensely popular amongst the general public, and the fifth and sixth volumes were awarded prestigious literary prizes in France and Canada for their extensive historical research and integration of archival documents. The series even gained political recognition in 2012 as the centerpiece and guiding narrative for the special exhibit, “Algérie 1830‐1962 with Jacques Ferrandez, 130 years of French military presence in Algeria,” held at Paris’s Musée de l’Armée.

Notwithstanding this positive reception from the public, French literary critics, and the Army Museum, some scholars have suggested that Ferrandez’s 10-volume masterpiece nonetheless perpetuates orientalist stereotypes and colonial nostalgia. Critical scholarship on Carnets d’Orient has, until now, left important issues of colonial land development policies un-interrogated. Using ecocriticism as an interpretative framework — which allows us to train our focus on representations of food and agricultural policy — opens up new understandings of the series and complicates some of the more monolithic interpretations of the graphic novels as works of nostalgia.

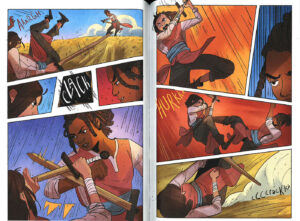

Central to volumes 1-3, the themes of land ownership, crop development, and food security merit further examination because Carnets d’Orient tends to whitewash early settler colonialism, a period which ultimately disrupted the agrarian foundation of the Algerian economy and had immeasurable long-lasting effects on Algerian society. The first volume, Djemilah (1994), depicts early French colonial operations in Algeria in 1853 through the eyes of Joseph, a fictional French painter. Like some painters of his time, Joseph travels to North Africa to immerse himself in Algerian culture, in order to paint authentic sceneries. Djemilah takes place “during the era of ‘quiet imperialism’ (1815-1882), marked by Europe’s industrial economic growth, with exporting grain and viticulture being one of the most profitable industries in Algeria” (Naylor).

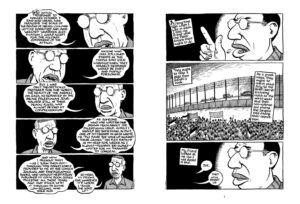

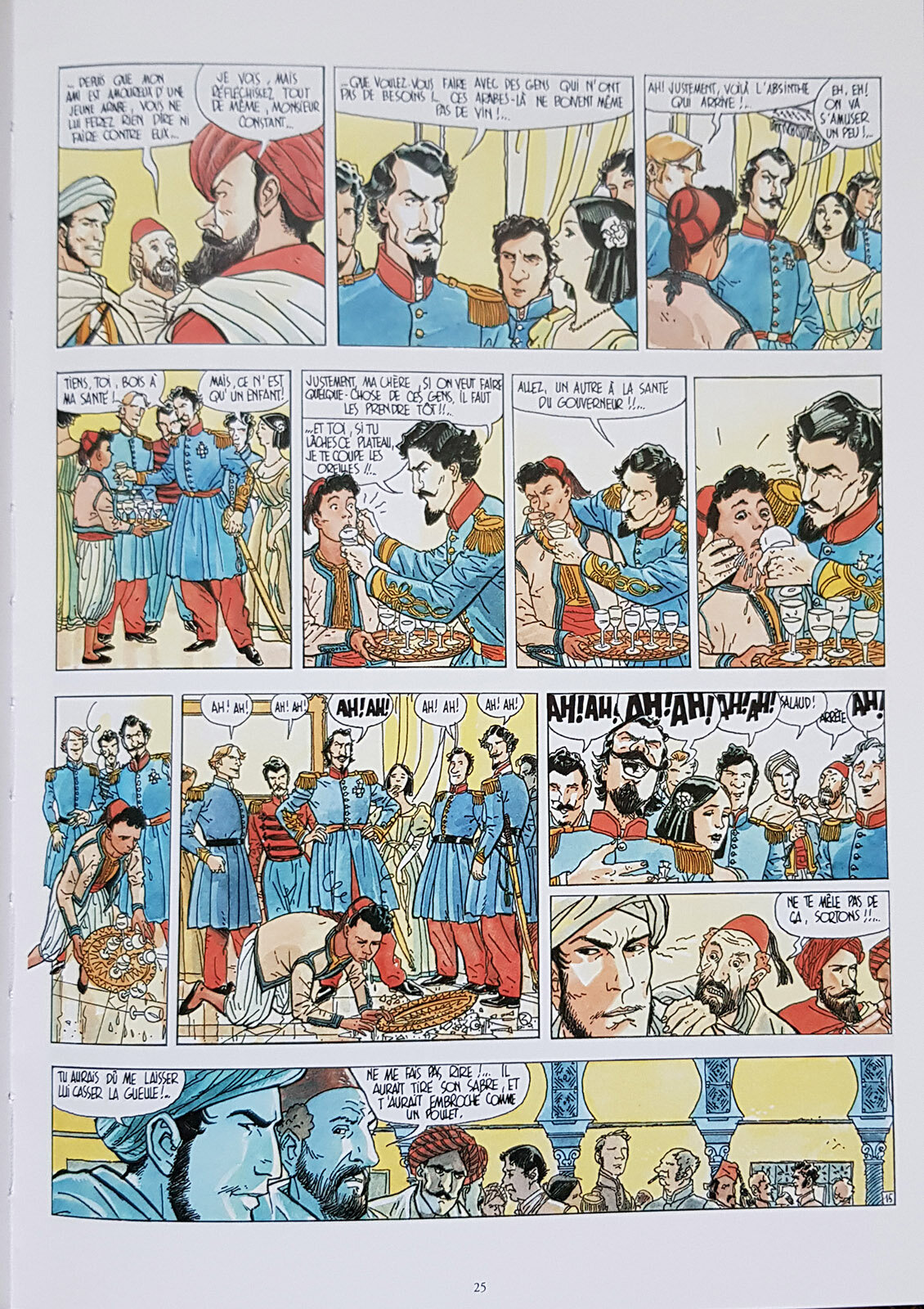

While there are many notable moments addressing agricultural development in Djemilah, one series of images in this graphic novel clearly depicts the French colonial agricultural system’s specific social and ethical implications. In this particular scene we find Joseph and his pied-noir friend Mario attending a cocktail party hosted by a French military officer in Alger (figure 1). Joseph is privy to a conversation between the officer and a French woman on the subject of Algerians refraining from wine consumption (figure 5). The French officer commands a nearby Algerian servant to toast to his good health, disregarding the fact that he is merely a child. Without any room for objection, the French officer forces two glasses of wine down the servant’s throat to honor the General’s health and that of the French Governor. Ingesting two glasses of wine causes the young servant to vomit immediately while simultaneously shattering several wine glasses as his serving tray falls to the ground. The room erupts into laughter at the expense of the servant’s humiliation.

Of course, the various types of colonial violence woven into this image sequence would merit further discussion. However, attention to the agricultural elements present in this scene will further contextualize the effects of French colonialism. While the power imbalance and violence between the general and the Algerian boy are obvious, less evident to the casual reader are the subtle references to colonial agricultural policy. Before landing on Algerian shores, French developers were aware that ancient Rome had cultivated vineyards across the Mediterranean coast. The investors also knew that these vineyards would be in various states of disarray since the arrival of Muslim invaders from the Arabian Peninsula in the mid-7th century. The plan to resurrect and plant new vineyards became urgent in the early 19th century due to a blight crisis affecting European vineyards. Once it became clear that the disease affecting European vineyards wouldn’t impact Algerian crops, the French colonial administration and private investors responded to market demand by transforming Algeria into one of the largest producers of wine in the 19th century (Amin 100). In order to accomplish their lofty goal of making wine Algeria’s principal export, French developers seized Algerian lands historically designated for grain bearing and transformed them into massive vineyards devoted to the production of wine grapes, thus replacing existing food sources with viticulture destined for export, further creating “a land where hunger chronically haunted the colonized” (Naylor 156). Although Djemilah doesn’t explicitly depict malnourished Algerians, the act of force-feeding a young boy wine symbolizes the forced dietary changes in local Algerian communities at the expense of capitalist farming.

Wine is obviously an essential aspect of French gastronomy and is a foundational element of French cultural identity. In other words, wine symbolizes France. The above-mentioned scene in Djemilah shows French settlers disregarding the Algerian child’s Muslim customs and imposing their own cultural practices without considering that his religion considers alcohol to be a forbidden substance. In this moment of the novel, Algerians’ religious beliefs and basic needs are not a concern because Algeria functioned as a resource to increase the metropole’s wealth, reaffirm France’s strong reputation in Europe, and secure economic control. The depiction of forced wine consumption illuminates more broadly the pernicious reality of la mission civilisatrice, because “Viticulture symbolized the severity of colonialism upon the colonized. The physical transformation of the land was also a cultural affront, given Islam’s proscription of alcohol” (Naylor 156). Vomiting wine metonymically functions as a physical rejection of the culture that French institutions forced onto Algerians. The young Algerian choking violently illuminates the colonial administration weaponizing wine — and, ultimately, French culture — to deprive this Algerian of food sources and compromise his religious beliefs. Reading Ferrandez’s scene centered around military violence through a food and land-centered perspective ironically contradicts the very institution proclaiming the series’ neutrality.

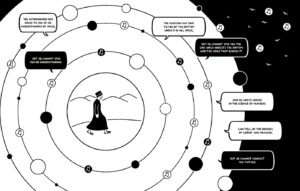

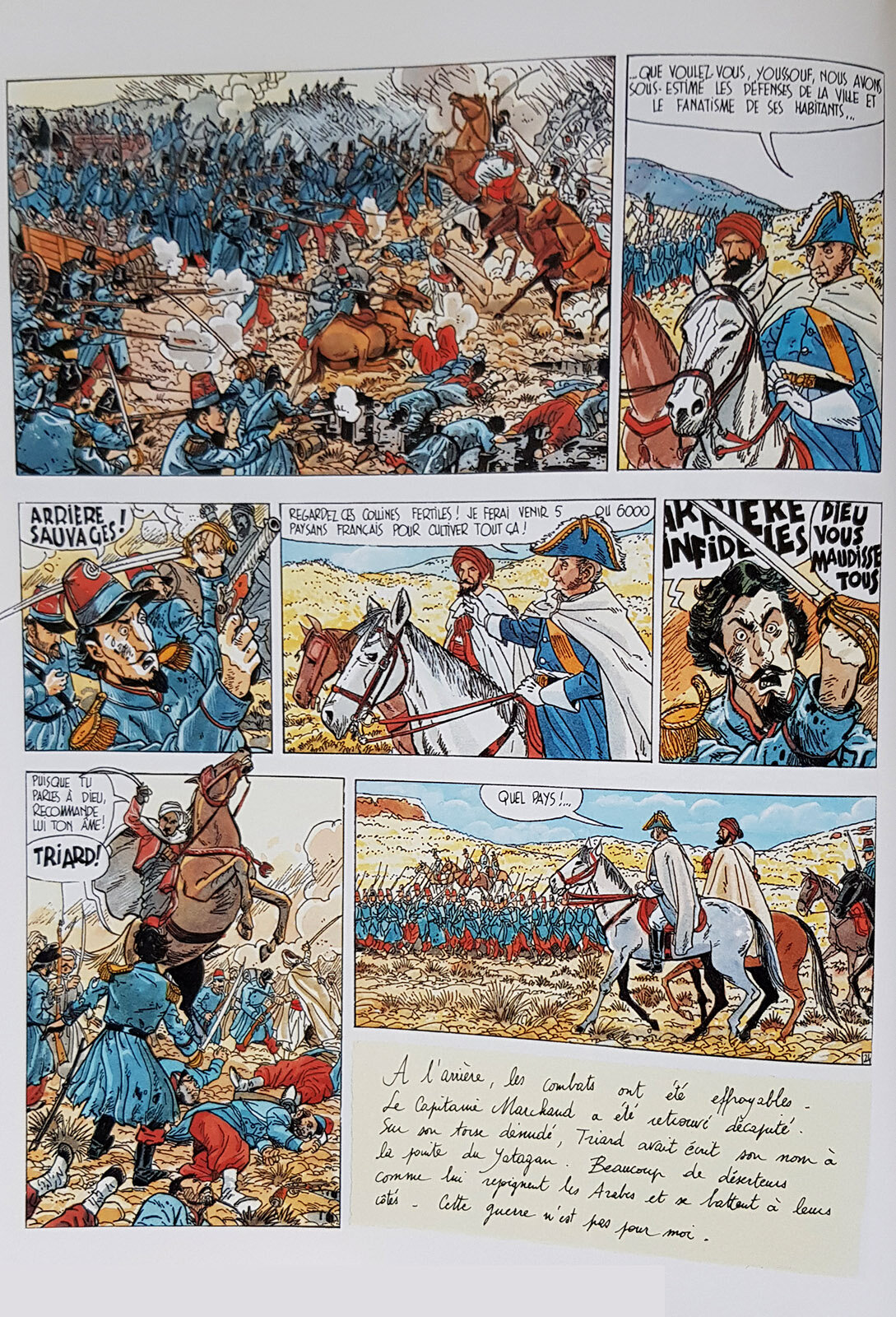

The second image we’ll examine here speaks directly to the grandiose notion that Algeria possessed a bounty of unused land at her disposal, and that only France could mold Algerian land to its highest potential. In this scene, an Algerian fantasia ambushes Joseph and his traveling escorts. As the French army combats the fantasia, Joseph and the military officer (known only as le Maréchal) observe their surroundings while remaining unharmed and outside the battle’s threshold. Le Maréchal informs Joseph of his future plans, gesturing to the land around them: “Look at these fertile hills! I will send 5 or 6,000 French farmers to cultivate all this [land]!” (figure 4). Notwithstanding the fact that the illustration implies aridity and desolation, the fertile hills referenced are crucial resources for Algerian herding communities and the existing trade-economy. Acquisitions such as those attributed to the fictional Maréchal would go on to disrupt the foundation of the Algerian economy and have immeasurable long-lasting effects on Algerian society. Private investors and the French government used duplicitous language and underhanded tactics to deny tribes access to their most fertile lands, and ultimately eroded the existing multi-network trade-based economy (Bennoune). This erosion happened through the displacement of Algerian communities from their territories and confiscating their most cultivatable lands, consequentially leading to dire food shortages and starvation (Naylor 155). In sum, the Algerian economic network would begin to collapse due to the seizure of grazing land necessary to produce wool and livestock.

Bearing in mind that early writers in colonial Algeria “tended to exaggerate the political fragmentation of pre-colonial Algeria in order to prove that the country had ‘never formed a nation” as a way to justify French occupation and control of natural resources, it follows that portraying an underdeveloped agricultural network plays a principal role in crafting the never formed nation myth (Bennoune 18). Of course, lands were never truly vacant upon French arrival. Whether the land appeared to be in use or not, every bit of Algerian soil was on some level claimed by someone as belonging to their territory. Therefore, any French land acquisition had to be at the expense of someone home or food supply (Halvorsen). Thus, Djemilah again critiques la mission civilisatrice pillar of the colonial narrative through the fictional le Maréchal’s capitalist endeavors.

If we situate similar illustrations contextualizing food systems and colonial agricultural practices into the broader context of the graphic novel, it becomes clear just how easily readers can overlook them due to their indirect relationship to Joseph’s character arc. Appearing as seemingly superfluous elements in Djemilah, such as offhand comments in casual conversation, objects in the background, or an item of consumption, each moment complicates the dialogue around French colonialism in Algeria — whether it be artistic depictions of their land, written and oral descriptions related to land, or financial hardship due to destroyed local economies. Despite never being fully articulated in the series, the developmental endeavors alluded to in Djemilah leave an incomplete yet aesthetically beautiful representation of French colonialism. The graphic novel genre, known for being inexpensive and widely circulated, ensures that Ferrandez’s colonial nostalgia reaches the broadest possible audience. Adopting a postcolonial lens influenced by critical environmental studies centering around food and agriculture reframes representations of property acquisition and farming development that complicate the series’ proclaimed neutrality, thus uprooting colonial legacies that continue to influence environmental policies and production methods related to farming, vineyards, and land ownership in North Africa.

In a similar vein to Tin Tin in the Congo (1956) and other comix used for teaching France about their exotic colonies, Carnets d’Orient delights readers with ink sketches, chalk drawings, watercolor paintings, and authentic colonial photographs. In effect, these realistic illustrations impress upon readers a false sense of authenticity regarding French-Algerian colonial relations. If we consider Algerian advocacy groups’ widespread criticism of Benjamin Stora’s recent report detailing the memory of colonization and the Algerian war (presented to French President Emmanuel Macron in January 2021), it becomes clear that perceptions of the colonial period lack unification and stability. Given this ongoing political and social tension concerning Eurocentric narratives, Carnet d’Orient’s enormous popularity and prestigious accolades raise concerns over how deeply colonial narratives are rooted in cultural productions. Therefore, reexamining this graphic novel series with the goal of making visible its representation of exploitative land and agricultural policy is an important critical gesture, one that contributes to the broader project of questioning existing narratives and reframing Algerian history around Algerian voices. This type of ecocritical research might even prove to be a crucial tool in conversations around possible reparations to Algerians.

Works Cited

- Amin, Samir, et Michael Perl (trans.). The Maghreb in the Modern World: Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco. Penguin African Library. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- Atlas de l’Algérie : 1830-1960. Paris: Archives & culture, 2011.

- Belkacemi, Boualem. “Agriculture in 19th Century Colonial Algeria.” Maǧalla Al-Tārīk̲iyya al-Maġribiyya (Li-al-ʻahd al-Ḥadīt̲ Wa-al-Muʻāṣir); Revue d’histoire Maghrébine, 1999.

- Bennoune, Mahfoud. The Making of Contemporary Algeria, 1830-1987 : Colonial Upheavals and Post-Independence Development. Cambridge Middle East Library. Cambridge [England] ; Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Bertrand, Julien, (Algeria et France) Exposition universelle de 1889 (Paris. La viticulture algérienne. Alger: Giralt, 1889.

- Cooper, Austin R. “A Ray of Sunshine on French Tables”: Citrus Fruit, Colonial Agronomy, and French Rule in Algeria (1930–1962) ». Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 49, no 3 (1 juin 2019): 241‑72.

- Côte, Marc. “L’exploitation de la Mitidja, vitrine de l’entreprise coloniale?” In Histoire de l’Algérie à la période coloniale, 269‑74. Poche / Essais. Paris: La Découverte, 2014.

- Ferrandez, Jaques. Djemilah. Carnets d’Orient 1. Casterman, 1994.

- Flandrin, Jean Louis., Massimo Montanari, Albert Sonnenfeld, et Bernard Rosenberger. Food : A Culinary History from Antiquity to the Present. European Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

- Halvorsen, Kjell H. “Colonial Transformation of Agrarian Society in Algeria.” Journal of Peace Research 15, no 4 (1978): 323‑43.

- Mckinney, Mark. “Tout cela, je ne voulais pas le laisser perdre”: Colonial lieux de mémoire in the comic books of Jacques Ferrandez ». Modern & Contemporary France 9, no 1 (1 février 2001): 43‑53.

- Naylor, Phillip Chiviges. North Africa : A History from Antiquity to the Present. 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009.

- Rosenberger, Bernard. “Cultures complémentaires et nourritures de substitution au Maroc (XVe -XVIIIe siècle).” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 35, no 3‑4 (août 1980): 477‑503.

- Still, Edward. “Broken fantasias? Jacques Ferrandez and the chimeric quest for disillusionment.” Studies in Travel Writing 21, no 3 (3 juillet 2017): 293‑312.

University of Oxford. “What Is The Food System?” Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food. Consulted October 12, 2020. - Will Davis Swearingen. Moroccan Mirages : Agrarian Dreams and Deceptions, 1912-1986. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1987.