Jordan Elgrably

Let us be brutally honest with ourselves — Friday’s brazen attack on novelist Salman Rushdie is a threat to freedom of expression everywhere, but it is merely the latest incident in thousands of cases where writers, poets, journalists and filmmakers are censored, imprisoned and even killed. They are hounded as critical thinkers who dissent from the party line, blow the whistle on repressive governments, or because they dare to offend conservative sensibilities.

While we don’t yet know 24-year-old Hadi Matar’s motive for setting upon Rushdie with a knife, is there really any doubt that he did so because of the fatwa against the author of The Satanic Verses? As much as he might deny it, one would have a hard time believing him. I view this attack as emblematic of the kind of intolerance repressive states have for any criticism. The Saudi-sanctioned torture and murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 and the shocking assassination of Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh by an IDF soldier this May are two of the most egregious cases in point.

Turkey in the last several years has become one of the greatest oppressors of writers, academics and intellectuals, with the largest prison population of political detainees in continental Europe. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, consolidating his power, has fired over 5,000 academics and 50,000 schoolteachers, whose progressive politics or Kurdish heritage he disliked, or who as journalists/editors/publishers have been too outspoken, such as widely translated novelist and newspaper editor Ahmet Altan, 72. The author of such internationally admired works as the novels in his Ottoman Quartet and the prison memoir I Will Never See the World Again, Altan was sentenced to life in prison in 2016. He spent four years behind bars but was unexpectedly released last year. He said recently, “Prison didn’t extinguish my desire to write.”

Earlier this month, the Kurdish poet, writer and editor Meral Şimşek, a PEN International protégée, fled Turkey to Berlin seeking asylum, as she was facing another stiff prison sentence in her home town of Diyarbakir. Her case was to have been decided on July 18, but a judge postponed it to September 16, giving Şimşek the opportunity to escape certain conviction. In a text to this writer on August 8th, she lamented, “I am now in exile. I miss my homeland.”

Syrian writer Faraj Bayrakdar, author of the recently-translated collection of poetry A Dove in Free Flight, is a journalist and award-winning poet. In 1987 he was arrested by Hafez al-Assad’s regime on suspicion of belonging to the Party for Communist Action. Held incommunicado for nearly seven years, he was tortured and eventually sentenced to 15 years in prison, but 14 months shy of completing his sentence, he was granted amnesty and obtained asylum in Sweden. Similar cases include Iraqi writer Hassan Blasim, who found refuge in Finland, and Iraqi Assyrian writer Samuel Shimon, who after spending time in Iraqi, Syrian and Lebanese jails, found his way to London and, with Margaret Obank, founded Banipal.

Meanwhile the jails of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah El-Sissi are overflowing with thousands of political prisoners. According to a New York Times story last week, many are subjected to torture and refused lifesaving medications, and “more than a thousand people have died in Egyptian custody.” Well-known cases of Egyptian writer Ahmed Naji (now a regular contributor to The Markaz Review) and hunger-striker and author Alaa Abd El-Fattah (You Have Not Yet Been Defeated) are just the tip of the iceberg.

One would be remiss in not pointing out that while U.S. President Joe Biden publicly condemned the attack on Salman Rushdie over the weekend, he is a friend and ally to the leaders of Saudi Arabia, Israel, Turkey and Egypt. Talking out of both sides of his mouth, Biden has refused to investigate Israel’s murder of Shireen Abu Akleh and continues to do brisk business with Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS), Erdoğan and El-Sissi. Are we to therefore understand that human rights are expendable when weighed against the demands of geopolitics?

Alas, yes, so what are we to do about lip service when it comes to freedom of expression, enshrined in the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, yet readily dismissed where American and European allies are concerned?

Apart from supporting the work performed by NGOs such as Amnesty, Human Rights Watch and PEN, we might lend our backing to Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN), a nonprofit founded by Jamal Khashoggi that promotes democracy, the rule of law, and human rights for all of the peoples of the Middle East and North Africa. DAWN “focuses its research and advocacy on MENA governments with close ties to the United States and the military, diplomatic, and economic support that the US provides these governments, as that is where we have the greatest responsibility.”

Filmmakers at Risk

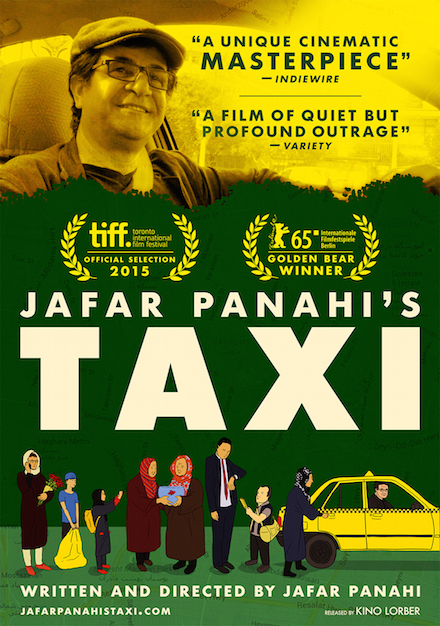

Iranian cinema is widely appreciated as among the best in the world, but in July, dissident Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi — previously convicted of “propaganda against the system” — was ordered to serve out a six-year sentence in Tehran. He was one of three prominent Iranian filmmakers who were arrested in June — the other two were Mohammad Rasoulof and Mostafa Al-Amad.

The International Coalition for Filmmakers at Risk exists to advocate for directors such as Panahi, Rasoulof and Al-Amad. The ICFR is also going to bat for Iranian filmmakers Mina Keshavarz and Firouzeh Khosravani, who in May were “were arrested in Tehran after their homes were searched and their personal and professional belongings such as mobile phones, harddrives and laptops were confiscated. On 17 May, Keshavarz and Khosravani were released on bail and banned from leaving the country for six months. There has been no official charge since their arrest.”

It’s hard to know what prompted the arrests; the Islamic Republic has remained taciturn on the matter. However, rumors from Tehran suggest that Khosravani was arrested for attending a documentary festival in Istanbul that was also attended by an Israeli documentary filmmaker.

With such intimidation tactics, one might well wonder whether self-censorship is a growing concern for all those who would dare to criticize their own government in their creative work.

On Saturday, in a Guardian column, former English PEN director Jo Glanville argued that there has already been a terrible “retreat from freedom of expression — self-censorship replaced tolerance as desirable behavior in a society where free speech was still supposed to be a benchmark for human rights. And we’re all still suffering from that shift in all areas of public debate.”

Salman Rushdie has been among the most visible advocates for freedom of expression since he came out of hiding, after the 1989 fatwa against his life and the novel The Satanic Verses, issued by a dying Ayatollah Khomeini. He noted in a 2012 talk in New York that terrorism is really the art of fear. “The only way you can defeat it is by deciding not to be afraid,” he said. But as a Jacobin columnist noted on Saturday, Rushdie has “faced much harsher consequences for his work than most artists ever will — particularly the psychological harm of enforced isolation and constant threat.”

The question is, will Rushdie’s stabbing inhibit other writers, filmmakers and journalists from speaking truth to power — artists who criticize sacred cows including governments, corporations and religion? Will we see our courage further eroded by extremist and repressive forces, which abound the world over, or will this strengthen our resolve?