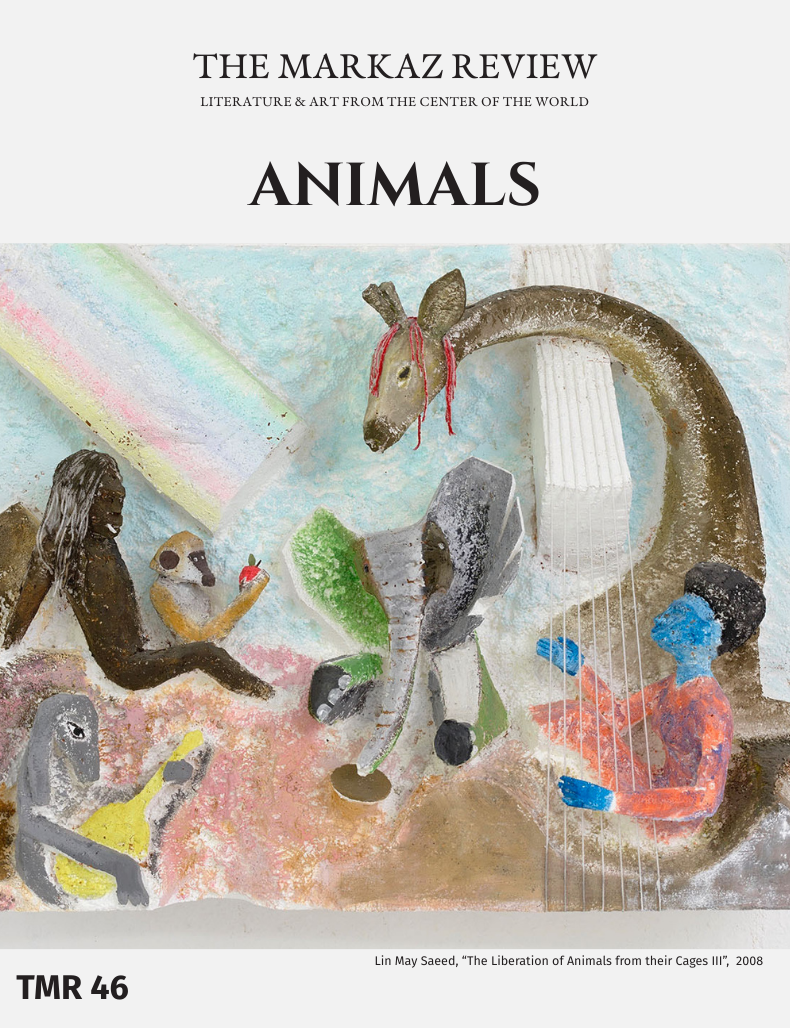

Talking lions, ducks, gazelles, traveling cats, magical dogs, and giraffes — welcome to the wonderful world of TMR’s animal issue.

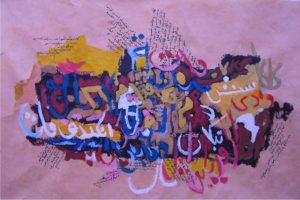

Sometimes the stories of animals can express human truths more viscerally than a straightforward account of people suffering. For instance, the lions of Baghdad and the tragedy of the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq were the subjects of the graphic novel, The Pride of Baghdad. Despite the fact that the lions had spent their whole lives in an Iraqi zoo, they didn’t speak Arabic — unlike the lions in “Mureen/Lion School,” the 2016 Mesopotamian-inspired artwork-relief by this issue’s featured artist, Lin May Saeed (1973–2023). Iraq was the country of Saeed’s father. The sculptor who grew up in Germany also didn’t speak Arabic. However, as TMR’s art critic Arie Amaya-Akkermans writes, Saeed was “not interested in human metaphors or in the archaeological imagination of the past per se, but in a more transtemporal, transformational, intersectional gesture. [Her work] is about turning upside down the utilitarian hierarchies of social relations that fashioned the world into the binary of human and animal.”

In the Anthropocene epoch of rapid climate change, increasing numbers of animals, birds, and fish are on the precipice of extinction. This has made human research into animal cognition all the more prescient. New studies show that the ordinary crow can recognize the faces of people. These incredibly intelligent birds don’t forget, hold grudges, and repeatedly dive-bomb people who have harmed them. Recently, philosopher of animal minds Susana Monsó has spoken about orcas, which like elephants, have an understanding of death and mourn their dead offspring.

The November issue of The Markaz Review, themed on animals, deliberately eschews the binary relationship between the proverbial “man and beast.” The artwork, art criticism, prison and family memoirs, travel writing, fiction, essays, and poetry featured here go beyond the politics of the eating, exploitation, and abuse of animals to reach a new level of understanding. And in many instances, it is inspirational.

Manus Island

The Kurdish Iranian author Behrouz Boochani escaped from Iran on a small boat and arrived in Australia, only to be imprisoned in one of the country’s notorious offshore detention centers. During his six years in the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre (MIRCP) on a remote island of Papua New Guinea, he and others endured untold levels of hardship, fear, and starvation. There, he met 43-year-old Mansour Shoushtari, someone the journalist and author of No Friend but the Mountains, describes as “The Man Who Loves Ducks.” Shoushtari was known to feed the scraps of the little food he was given to the island’s crabs and feral dogs. He didn’t have a bad word for anyone, even the Australian minister responsible for his and Boochani’s imprisonment. A friendship with a duck gave Shoushtari the will to live when he was close to death in a people-smuggler’s boat on the high seas.

In the issue, the exponentially increasing numbers of cats in “The Felines that Leave Us, and the Humans that Left,” by Farnaz Haeri, translated from Persian into English by Salar Abdoh, has distant echoes of JD Vance’s comment about “crazy cat ladies.” But this is Tehran and a glimpse into a remarkably fluid, open household belonging to Haeri, an essayist and literary translator who has translated the novels of Haruki Murakami into Persian. Because of the political pressures in her country, people are often forced to leave or simply disappear. Then there are other pressures that can fracture families all over the world. In Haeri’s case, it fell upon her, the single sister and auntie, to provide a safe and unusally lively haven for the growing number of pets and children who came and lived with her.

Cats are by far one of the most successful animal species on earth and people love them greatly. Izzeldin Bukhari, the vegetarian chef and founder of the Jerusalem-based Sacred Cuisine pop-up kitchen, contributes travel writing at its very best — humorous, suprising, capturing a keen sense of place. In “The Ballad of Lulu and Amina,” Bukhari’s sister is getting married in Gaza. The conundrum is not only whether the Israeli soldiers will let a cat in a birdcage through the Erez checkpoint, but if Hamas officials will allow Bukhari and his sister’s beloved feline into the Strip.

Birds

Pigeons are much maligned in Western cities; they are usually regarded as no more than “flying rats.” But on the wing they remain inspirational, and not just in the countries of the Middle East. Sometimes the sounds from homemade whistles, worn by pigeons, can be heard floating over the city of Beijing, and then fade away as the birds fly further afield. Homing pigeons in Amman can go for 20,000 dinars ($28,000 USD). There are class implications in the selling, breeding and flying of these birds. For enthusiast Yahia Lababidi, emotion runs deep. His hybrid essay, “Pigeon Love,” is part poetry, part paean, to the birds that make his hobby and life worthwhile.

Birds have long been a fascinating subject for artists and many from the region include them or have an affinity with them in their work, according to Iraqi curator Amin Alsaden. Certain texts stand as seminal animal poems and stories. One is The Conference of the Birds, also known as the “Speech of the Birds,” written in 1177 by the Persian Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar, which Iranian poet and The Markaz Review’s poetry editor Sholeh Wolpé reads online (W.W. Norton published her translation of Attar’s The Conference of the Birds a few years ago). Equally significant have been the animal fables of Kalīlah wa-Dimnah, attributed to Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ from the eighth century. The illuminated manuscripts of these morality tales produced during the Persian, Mughal, and Ottoman empires show a level of sophistication, in word play and visual interpretation, not seen in the classical western versions of animal fables, Aesop.

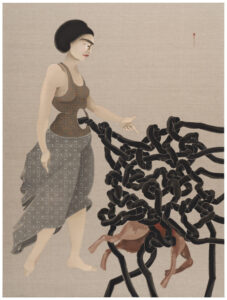

For The Markaz Review, Naimi Morelli in “Beyond Our Gaze: Rethinking Animals in Contemporary Art” considers artists’ reasons for the inclusion and depiction of animals in their work. For Khaled Hafez, “animals function not as passive props but as lively embodiments of the many cultural and social contradictions that shape contemporary Egyptian life.” Another Egyptian, the artist Wael Shawky, makes great use of animals in his puppet series, Cabaret Crusades, an adaptation of Amin Maalouf’s 1984 historical study, The Crusades through Arab Eyes.

As Morelli writes: “By turning to animals instead of humans, Shawky asks viewers to consider how cultures construct and distort the enemy ‘other’ in the telling of history, an observation with significant implications for understanding modern East-West relations.” Another artist she writes about is Walid Raad. In his series, We Have Never Been So Populated, a right-wing Christian militia weaponizes invasive birds during the Lebanese civil war: “Their goal was to release these birds into enemy territories to disrupt ecosystems.” Sounds a lot like those bothersome crows and the grudges they hold.

In “Artists & Animals” other artists use animals strictly as metaphors — for refugees and migrants — as in A Proposal for Parakeets by Adham Faramawy; or the last vestiges of a floating Palestinian presence in Hebron in Mohammad Saqdih’s installation, The Fish of Al-Khalil. The Tunisian graffiti artist Ouma whose work also illustrates the animals issue has a special affinity with the owl and the wisdom the bird represents, while Iranian Tarlan Lotfizadeh reacts to the pig, an animal she had no experience of since she grew up in an Islamic country. The automation used in swine slaughter, and the color known as “fairy tale pink” of their skin — the artist duplicates by using some of her own blood — reminded Lotfizadeh of the people killed by the Iranian regime.

Dogs in the issue also provide an occasion for evoking the supernatural. “Habib” by Ghassan Ghassan takes its title from a pet’s name. A bombing in Gaza destroys an entire family except for the protagonist of the short story and his beloved dog. While the people of Gaza have difficulty fleeing the war, there is a healthy trade in getting animals out — perhaps a metaphor for the lack of action on the part of Arab regimes. The main character and the dog almost get free, but “Habib” is an intriguing ghost story with a twist.

The pioneer of Kuwaiti fiction, Laila Al-Othman, contributes to the issue the short story “A Market for Titles,” translated from the Arabic by Ibrahim Fawzy. It is a cautionary tale told from a sheepdog’s point of view, like Mikail Bulgakov’s novella, Heart of a Dog. Whether in revolutionary Russia or Kuwait, dogs can have a tough time especially if their owners are abusive. This poor Arab dog has to deal with a greedy woman criminal. He suffers greatly until he decides to take matters into not his own paws but his mouth.

Escape and erasure

It was the graceful gazelle that populated the deserts of the Arab Peninsula which gave the Arabs the name for their best known lyrical form, the ghazal. These poems, usually about love, longing, or the metaphysical, were often song by Arab, Persian, Indian and Pakistani musicians. The language is poetic and sensual in Shadab Zeest Hashmi’s short story “Gazelles Leaping,” which leaves the minds of reader in a contented state. The Pakistani-American poet has a great interest in Sufism, and in her short story, a mythical gazelle makes it to the moon, and eventually finds its way home again.

In “The Palestinian Gazelle,” artist, Manal Mahamid, meanwhile, created an entire exhibition around Palestine’s beloved grazer. It became personal for her, she writes, when she went to the zoo in Israel, “where I noticed a sign at a gazelle enclosure. In Arabic and English, it read “The Palestinian Gazelle,” but in Hebrew, it was labeled “The Israeli Gazelle.” This deliberate reclassification was more than just a change of words — it was an act of environmental violence, a clear attempt to overwrite a piece of the landscape’s story. It echoed a broader policy of naming, erasing, and reassigning identities within the land itself.”

Speaking of getting home, getting back can be difficult to do. Last month, two blue-throated macaws — still in their infancy at two years old (macaws can live until they’re 60) — were let out of their enclosure at London Zoo. Temporary escape was part of Lilly and Margo’s regular exercise. Typically they would fly around Regent’s Park and come back. This time they disappeared for six days. The zoo had issued an alert and the large, blue and yellow, long-tailed parrots were eventually discovered 60 miles away in someone’s backyard near Cambridge. The birds’ keepers were quickly dispatched there. When Lilly and Margo saw them they flew into their arms and were rewarded with pumpkin seeds and pecans. Animals, like humans, yearn for freedom; yet equally crave the comfort of belonging, friendship, and safety.

I had lived for 16 years in London before I started riding my bike to the zoo. It was during the terrible days of Covid, when people were dying and NHS doctors and nurses were wearing plastic trash bags for protection. I would stand on the street outside the gates in front of the giraffe house. The two giraffes that live there are sisters. Sometimes one of them, usually Maggie, because Molly was more reserved and stayed inside, would step through the plastic strips that hung over the very tall, opened stable door, and nibble at a cabbage that had been tied near the top of the building. She didn’t have to stretch out her long neck to reach it. Watching the giraffes in the zoo somehow allayed my fears and left me strangely hopeful.

Wikipedia draws from etymology dictionaries as well as Persian lexicon and language institutes, and provides the etymology of the animal’s name. Giraffe:

originated in the Arabic word zarāfah (زرافة), ultimately came from the Persian زُرنَاپَا (zurnāpā), a compound of زُرنَا (zurnā, “flute, zurna”) and پَا (pā, “leg”). In early Modern English the spellings jarraf and ziraph were used, probably directly from the Arabic, and in Middle English jarraf and ziraph, gerfauntz. The Italian form giraffa arose in the 1590s.

The first long-legged ruminants brought to Florence wandered the streets and were fed onions by people from their balconies and rooftops.

For homo sapiens, the existence of animals can be a kind of therapy when they don’t fall victim to the ills of a human-made world. I still visit the giraffes once a week. However, I’ve made a new friend at one of the city farms. He stands over his woodpile and has the expression of someone composing poetry. I admire his serenity and creativity. The winter coat he is growing is soft and his name is Hamish. He’s a pygmy goat.