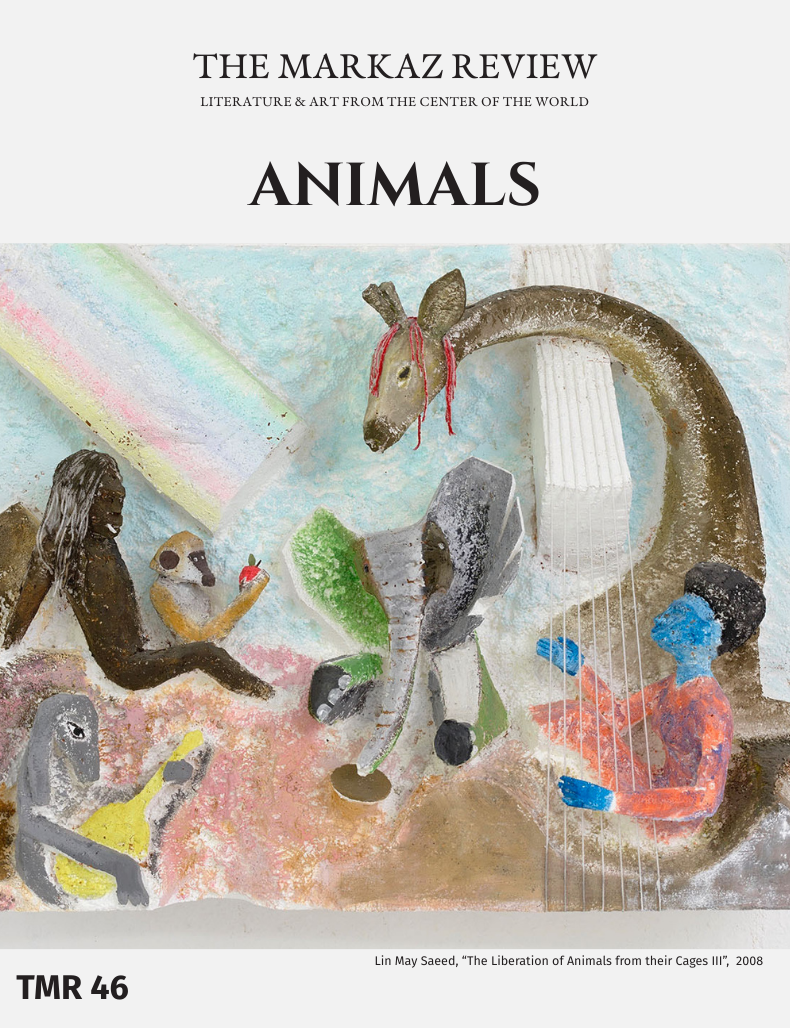

Four artists choose their animals, birds and fish as inspiration, cautionary tale, or metaphor.

Jelena Sofronijevic on Adham Faramawy

Adham Faramawy’s works are truly site-specific, responses to ecologies local to their display. Sometimes, these relations are deeply rooted, drawing from non-indigenous plants in London, a city “native” to their practice, if not their early years. Others are more transient. For the artist, birds are simply “another migrant that made this island their home,” and frequent avatars in their videos, sculptural assemblages, and film installations. A proposal for a parakeet’s garden (2022) considers this threatening or invasive species as a symbol for political anxieties over migration, singing in solidarity with refugees arriving in England seeking a home. A proposal joins their most recent commission at Focal Point Gallery in Southend, “Birds of Sorrow” (2024), a consideration of water, waste, and life through the lens of Barking and Dagenham’s shore-dwelling birds, developed alongside a series of encounters with the local community.

Living and working in London, Faramawy was born in Dubai, and is Egyptian. Navigating these geographies through land and water, their works expose the flows of migration, and legacies of colonial and capitalist extraction, that underlie contemporary nation states. Crucially, Faramawy’s work considers the natural environment in relation to marginalized communities; their home in Newham in the East of London, one of the city’s poorest boroughs, experiences some of the worst air pollution. “Birds of Sorrow” engulfs its viewers within the Great Smog of London of the 1950s, and offers glimpses or gaps with elements of myth and speculation, including scenes where the Children of Lir, figures of Irish folklore, transform from human to bird form. Faramawy’s take to the skies perhaps also is one which explores the possibilities of freedoms, within this literal suffocation. Both “A proposal” and “Birds of Sorrow” explore the complex relationships between “natural” bodies and place, finding likenesses in the fluid identities and behaviours of plants, animals, and more-than-human beings. Their UAL 20/20 commission for Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge will, no doubt, bring the artist’s practice from the outside in, to consider these entangled personal and family histories in domestic settings.

Still, Southend (on-Sea) is an ideal location for the exhibition of an artist whose work delves into the knowledge held in waters. Their exhibition takes its name from the commission which received the Frieze London Artist Award in 2023, following migrations, colonization, and ecological collapse from the river Nile to the Thames — themes particularly resonant with previous awardees as Himali Singh Soin and Abbas Zahedi. And these deceitful waters follows multiple performances in port cities across the UK, from the Serpentine and Tate Modern and Britain in London, and the Bluecoat in Liverpool, alongside a major exhibition at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff earlier this year. Faramawy’s new film, The Cyclamen and the Cedar, the culmination of their recent residency at Kettle’s Yard as part of 20/20, a three-year program with the UAL Decolonising Arts Institute, will be launched at the London gallery, on November 6.

Where the artists’ works have previously been screened or performed individually, In the simmering air and the flows of the undercurrent marked the first time they exhibited paintings at a public institution, allowing audiences to sit with their practice, and body of work across media. These ongoing flows — from the capital — might be their most generative yet.

Tarlan Lotfizadeh on Mein Reines Schwein Sein

When I was invited to participate in an exhibition exploring brutality toward pigs in Germany, I initially found the theme distant and unfamiliar. Having been born and raised in Iran, pigs were largely absent from my life due to the Islamic prohibition against eating pork. I had never even seen one, so I considered withdrawing, feeling the topic irrelevant to my personal experience. However, this disconnection reminded me of another form of brutality I had witnessed firsthand — the violence inflicted on humans. Both forms of suffering reduce the body to a mere site of pain and control. This realization became the foundation for my project, drawing a parallel between the suffering of animal and human bodies within systems of power.

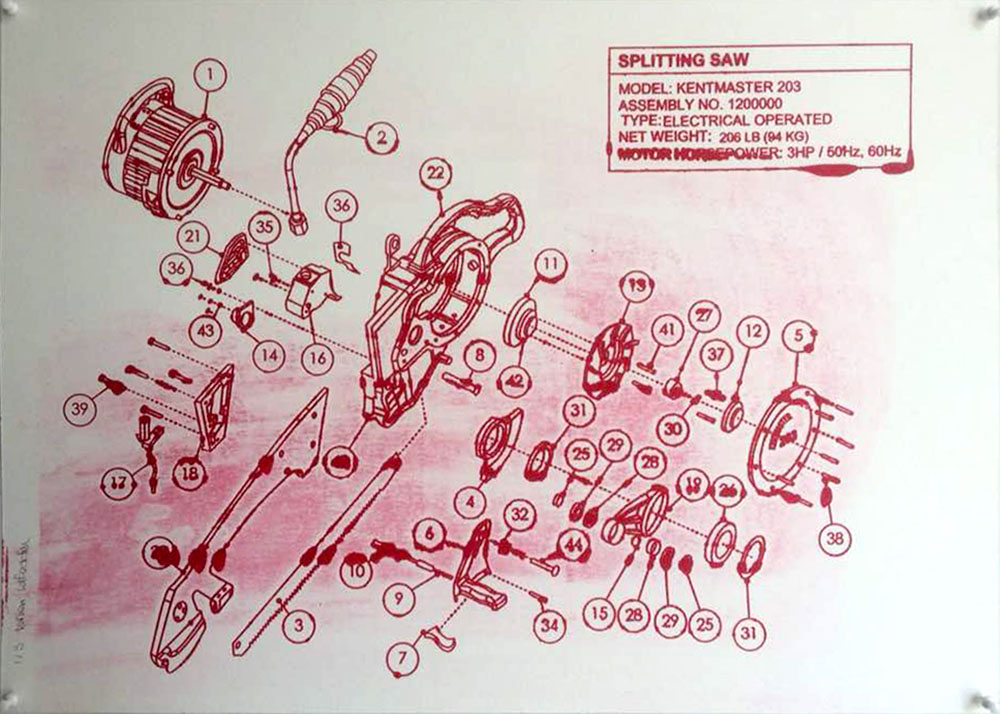

In “Kentmaster 203,” I explore this theme further through a silk-screen print of an exploded diagram of a slaughterhouse saw. Inspired by Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, which examines how evil becomes routine and embedded within bureaucratic systems, the diagram dissects the saw’s mechanical parts, detaching them from the experience of pain and suffering. This cold, methodical depiction mirrors how systems of violence — whether in slaughterhouses or oppressive regimes — operate. By using pigments mixed with my own blood, I add a visceral, tangible connection to the brutality. The piece invites viewers to consider how cruelty becomes normalized within institutional processes, turning bodies into objects of suffering.

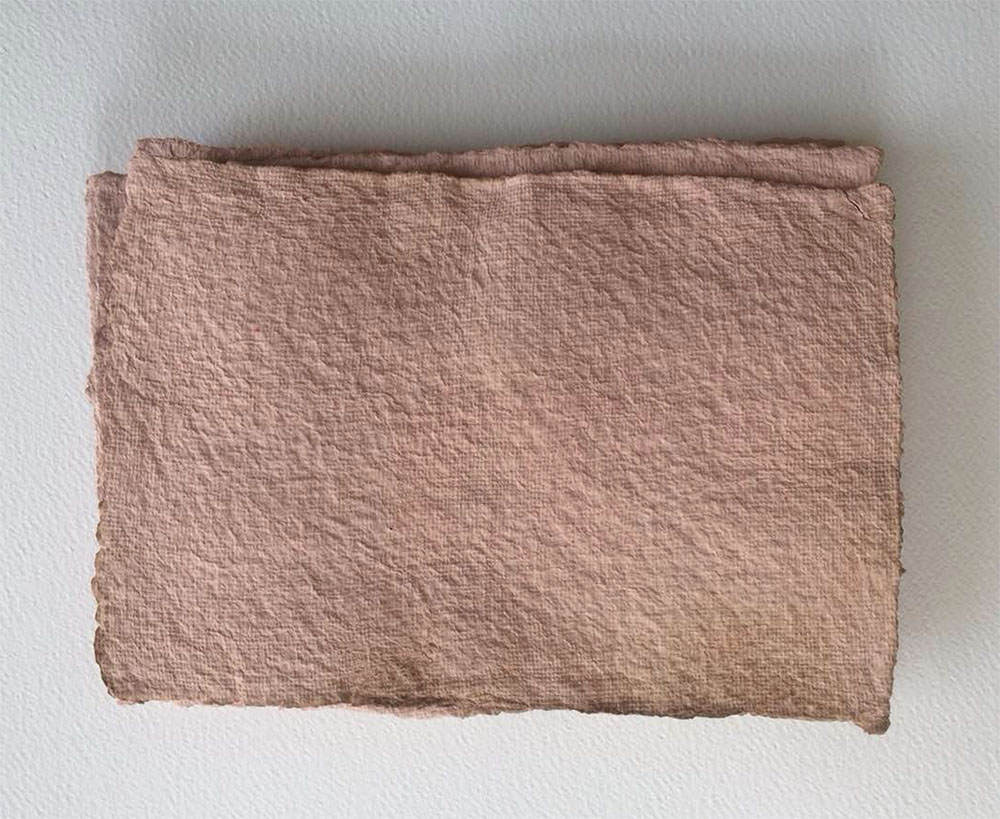

This theme of hidden brutality, masked by layers of innocence or normalcy, is also present in “# f2c2d1.” This sculpture, made from five sheets of handmade paper in a soft pink hue, is titled after the hex code for fairy tale pink. However, the delicate color is deceptive. The paper was created from a pulp made of slaughterhouse equipment catalogs, with the pink hue derived from the reddish images of flesh in those catalogs, mixed with my own blood. At first glance, the paper appears fragile and whimsical, but its creation reveals a much darker process. This contrast between appearance and reality symbolizes how suffering is often hidden beneath layers of normalcy. The fragility of the paper reflects the vulnerability of bodies, whose suffering is concealed beneath a normalized exterior, requiring deeper investigation to uncover the truth.

The most personal work in the project, “slaughterme,” is a video performance rooted in a childhood memory from the Iran–Iraq War. My sister and I used to play a game by the glass door of our home, pretending to be pigs while pushing our faces toward the glass. In the video performance, I recreate this game, but the innocence of childhood is overshadowed by discomfort, pain, and suffering. Sliding along the glass, I explore the thin boundary between my adult self and the child I once was. The glass becomes a symbolic barrier, separating me from the viewer and evoking the feeling of being “othered.” The piece invites viewers to reflect on their role as observers and witnesses of suffering, and how easily we become complicit in systems of violence.

Through this project, I explore how the body becomes a site where control, pain, and power intersect, revealing how systems of brutality reduce the body to an object of suffering — a place where control, pain, and power intersect.

Siobhán Shilton, Ouma and the Owl

Ouméma Bouassida, alias “Ouma,” is a graffiti artist based in Sfax, Tunisia. Ouméma began to practice graffiti in 2011 after the Tunisian Revolution. She relates how passers-by have often been surprised to see a woman — particularly a hijabi woman — practicing graffiti. The artist aims to change perceptions: “through my art, I defend, today, the Arab, Muslim, artist, veiled and free woman! That’s what I am, in fact.”

Ouméma’s graffiti is, according to Fatima Sadiqi, an example of the alternative feminist voices and strategies which have emerged in North Africa since the revolutions and protests in the MENA region since 2011. Yet, this artist’s work does not only subvert perceptions by reclaiming public space. Ouméma’s presentation of her work — and of herself together with her work — on social media enhances her interventions. In photographs and videos of the artist, process and performance are prioritized over the completed mural. These images highlight her presence and visibility as a hijabi graffiti artist, crossing spaces and art forms that have traditionally been gendered. Ouma-Ouméma’s posts alternate between her multiple professional and personal identities, from artist and fashion designer to mother, reshaping the image of the graffiti artist in and beyond Tunisia.

Many of these videos and photographs show a close-up of Ouméma with her hands covering her face, fingers parted either side of her eyes. This gesture ironically and playfully conceals yet reveals the artist’s face. It calls to mind the fact that graffiti artists traditionally work undercover, while Ouméma’s practice is highly visible, and her visibility in public space is crucial to her message. This gesture ironically links the two sides of her identity as Muslim and graffiti artist. It is reminiscent of an owl, a recurrent motif across the artist’s work.

A video of Ouméma’s mural of an owl wearing an elaborate Amazigh necklace and carrying on its back a red high-top Converse highlights the significance of this bird for the artist. She explains that the owl is “the only bird that flies and doesn’t make a noise with its wings, so it always achieves its objectives,” while the Converse represents youth. The image echoes Ouméma’s own journey as an artist. Watching the video, this connection between the artist and the “feminized” owl might be made by viewers as the artist’s discussion of this symbolism immediately follows her comments on her career: following the revolution, she could veil and therefore study and become an artist with opportunities to travel. The connection between Ouméma and the owl also emerges visually: the bright blue colour she wears matches the dominant colour in the mural. The image of Amazigh jewellery on her T-shirt, which she designed, can be linked with the jewellery in the image. While her footwear is not visible on this occasion, she can often be seen wearing Converse. In her portfolio, the artist perceives the owl (viewed as a symbol of wisdom and a spiritual guide in many traditions) as representing, in these times, a moment of transition or important change.

Charlotte Bank on Mohammad Shaqdih

Entering Mohammad Shaqdih’s installation “The Fish of Al-Khalil,” 2016, is like entering a magical world, an imaginary aquarium or an otherworldly space where fish are floating in the air. Strings of small, playful fish in blue, turquoise, green, and brown colors are hanging from the ceiling, attached to transparent cords. However, this seemingly joyful space is connected to a history about the lost hopes for touristic and commercial development in the city of Al-Khalil (Hebron) in the West Bank. The fish were collected by the artist from a disused glass workshop, a business with a long tradition. In the hands of the same family for many generations, it had been known for its small, colorful fish that had become popular souvenirs.

Faced with the increasing encroachment on its territory by the ever-expanding Israeli settlements, access became almost impossible, ultimately leading to the workshop’s bankruptcy and forcing it to close. With this closure, yet another chapter of glass production in the city was ended, an artisanal tradition whose roots go back many centuries. More recently, “Hebron glass” as it is widely known, has been largely made from recycled glass, adding an ecological dimension to its production. But it is a tradition becoming more and more extinct as workshops and businesses are squeezed out of existence.

This troubled backstory appears to be quite far from the cheerful little fish that populate the space of Mohammad Shaqdih’s installation. They are quite isolated from one another, in contrast to the close-knit communities so characteristic of old Arab city neighbourhoods. And they face in different directions, thus becoming a metaphor for the expulsion and dispersion of the city’s indigenous population. Through their vivid colors they may be seen to represent strength, and the fact that glass is in many ways indestructible, forever re-usable and adaptable may be read as a metaphor for the Palestinian (unwanted) condition.

The installation offers an occasion for visitors to engage with its delicate objects as witnesses to a disappearing artisanal tradition that is so closely connected to the Palestinian city of Al-Khalil. During a time when Palestinian lives and livelihoods are destroyed on a daily basis, insisting on the existence of these historical spaces and continuities becomes ever more pertinent.