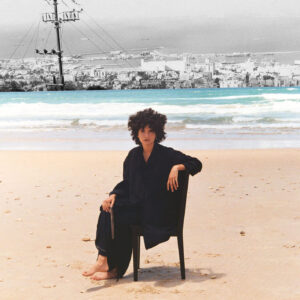

Artist Manal Mahamid shares the evolution of her exhibition The Palestinian Gazelle, which has been on display in Bethlehem, Haifa and Ramallah, as well as in Niklass, Belgium, Toronto and at the 2024 Dubai Art Fair.

As a Palestinian artist working across sculpture, video and photography, my practice is deeply rooted in exploring the complex intersections between colonialism, identity, and the altered landscapes of my homeland. I use art to confront the ways in which colonial regimes reshape not only human narratives but also the ecological realities of a place. I believe that land, animals, and plants are not passive victims in this transformation; they are active bearers of history, witnesses to the trauma of erasure, and symbols of resilience. My project, The Palestinian Gazelle, emerged from these reflections and became a pivotal part of my ongoing exploration of environmental justice and ecological resistance.

The project began with a personal experience at a zoo in Israel, where I noticed a sign at a gazelle enclosure. In Arabic and English, it read “The Palestinian Gazelle,” but in Hebrew, it was labeled “The Israeli Gazelle.” This deliberate reclassification was more than just a change of words — it was an act of environmental violence, a clear attempt to overwrite a piece of the landscape’s story. It echoed a broader policy of naming, erasing, and reassigning identities within the land itself. I realized that the renaming of the gazelle was symbolic of a larger process where even nature is co-opted and redefined by the occupying power. This manipulation of ecological narratives reflects a form of ecological colonialism — where the natural world is altered to reflect the colonizer’s claim over the land and its history.

The gazelle has long been an iconic symbol in Palestinian culture, representing beauty, grace, and a connection to the land that predates political borders. But in this encounter, I saw how even the natural world is not spared from colonial narratives that attempt to sever the people’s connection to their environment. A later experience in the same zoo deepened the project further. I saw a gazelle with an amputated leg, and when I asked, the zookeeper explained that they had “saved” it by cutting off its limb. This explanation struck me as disturbingly familiar. It reflected the paradox of colonialism: to preserve something by mutilating it, to “save” it by altering it beyond recognition.

From this encounter, the gazelle became a powerful metaphor in my work. To me, the amputated limb mirrors the experience of Palestinians, whose connection to their land has been severed, fragmented, and rewritten. Yet, despite the dismemberment, the gazelle stands, dignified and defiant. It symbolizes the broader fight for environmental justice, where the struggle is not only about protecting land and species but also about preserving cultural identities and historical narratives against a backdrop of systemic erasure.

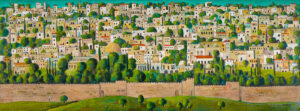

In creating The Palestinian Gazelle, I aimed to highlight how colonial forces not only control human narratives but also manipulate ecological ones. Through video, sculpture, and mixed media, I traced the journeys of the gazelle across a divided and militarized landscape, defying checkpoints, borders, and fences. Running through these terrains, I wanted to capture the absurdity of imposed boundaries on a land that once flowed freely. The act of running became a visual metaphor for resistance: a refusal to accept fragmentation and a reclamation of the land’s natural continuity, challenging both environmental degradation and the politics of ecological apartheid that seek to compartmentalize and control movement.

My large-scale sculpture of the amputated gazelle is a deliberate representation of this resilience. Despite its missing limb, the gazelle stands proud — not as a pitiful creature, but as a survivor—a reflection of a disrupted yet unbroken identity. It represents a landscape that, like the gazelle, has been cut apart and claimed, yet continues to endure. By emphasizing the mutilated yet enduring body of the gazelle, I wanted to address the broader issues of environmental trauma — where the land and its inhabitants bear the visible and invisible scars of conflict.

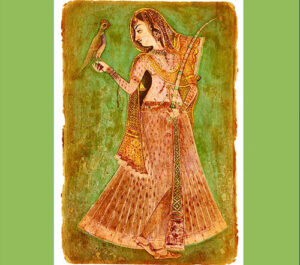

The use of the gazelle in my work is a way of reasserting its true identity — one that is deeply entwined with the history and ecology of Palestine. I am fascinated by how the animal’s image appears throughout Arab literature, poetry, and music as a symbol of longing and connection to the land. It is an image that belongs to a time before borders and barbed wire, when the land was whole. In my work, I aim to make visible the tension between what the land was, what it is forced to be, and what it could be if freed from these constraints.

By placing the gazelle in landscapes that span from the north to the south of historic Palestine, I invite viewers to reimagine the land as it once was — continuous, whole, and resilient. I want people to see not just the physical beauty of the gazelle but the broader ecological and political story it tells. This is not just an animal; it is a living archive of a land under siege, a creature caught between survival and loss, and a reminder that even in the face of attempts to amputate its history, it endures.

Through The Palestinian Gazelle, I hope to address not only the political erasure of a people but also the environmental and ecological impacts of these narratives. The project is my way of reclaiming the landscape and asserting a form of ecological justice that insists on the inseparability of land, identity, and the natural world. For me, the gazelle’s journey is a story of interrupted yet unbroken continuity — an emblem of ecological and cultural endurance that refuses to be confined to the narrow definitions imposed by colonial narratives.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)