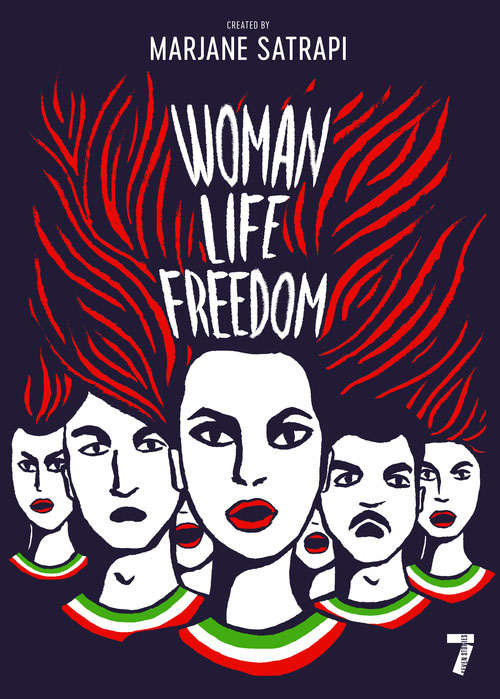

The new edited volume from Marjane Satrapi is a visually arresting collection of graphic storytelling about the Iranian women’s protest movement that began in September 2022. The book is a collaboration of activists, artists, journalists, and academics working together to depict the historic uprising — with comics that show what would be censored in photos and film in Iran — in solidarity with the Iranian people, in defense of feminism.

Woman, Life, Freedom by Marjane Satrapi, Joann Sfar, et al., translated by Una Dimitrijevic

Seven Stories Press 2024

ISBN 9781644214053

Katie Logan

“We’ve urgently got to change the public perception of Iran,” Marjane Satrapi pleads in the final selection of the new collected comics anthology, Woman, Life, Freedom. “Iranians are just like you. There are plenty of Marjanes in Iran.”

Some of those Marjanes — artists, migrants, students, activists — appear in and co-create the pages of Woman, Life, Freedom. The volume was shepherded into being by Satrapi, Alba Beccaria, and Beccaria’s editorial team at the French publishing house L’Iconoclaste. It strategically wields the Persepolis author’s fame to direct global attention toward the Iranian fight for democracy and equal rights, reignited by the murder of Mahsa Jina Amini at the hands of Iranian morality police in September 2022.

There are plenty of Marjanes and plenty of audiences in this collaborative undertaking. As Satrapi suggests above and in the anthology’s preface, one of its aims is to “explain what’s going on in Iran, to decipher events in all their complexity and nuance for a non-Iranian readership, and to help you understand them as fully as possible.” The other, she says is “to remind Iranians that they are not alone.” (my emphases)

The choice to engage both these audiences simultaneously illustrates the book’s ambitions and its operating philosophy. The story of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, or Jin, Jyan, Azadî in its Kurdish origins, cannot be told with only one voice or toward only a single conclusion. Satrapi, who notably distanced herself from comics following the success of Persepolis (2000–2003), Embroideries (2003), and Chicken with Plums (2004), contributes to this anthology a preface, an introductory essay, a two-page spread on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, and participation in the volume’s final comic “And Then?” The rest of the book is indebted to a multigenerational collective of writers, scholars, and artists with varied experiences inside and outside of Iran.

From the anthology’s opening essay, “A Persian Tale of Good and Evil,” Satrapi and her colleagues argue that the movement is not just a “momentary societal eruption.” Instead, they root their narration of Woman, Life, Freedom in a culture of women’s protests extending back decades if not centuries. The anthology’s writers trace that lineage through both myth and history to locate the “fierce women who break chains and inspire freedom.” The opening essay also identifies the institutional forces that conspire to maintain power; these include containment strategies like political violence, religious dictate, medical diagnoses, and economic control. Fatemeh Baraghâni-Tahereh delivered a sermon while unveiled in 1848; the ruler Naser al-Din Shah “ordered her execution through strangulation, a method of death reserved for women who dared to speak out.”

Subsequently, one of his daughters, Tadj es-Saltaneh, supported democracy and the Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911). Satrapi and Abbas Milani don’t mention es-Saltaneh’s forays into gender fluidity—a photograph of her dressed as a man exists in the Golestan Palace archives, the inspiration for Iranian photographer Amak Mahmoodian’s photobook Zanjir. However, the two do write that es-Saltaneh “was accused of ‘hysteria,’ a last resort for the wretched individuals who tremble before empowered women.” By highlighting the female leaders, scholars, writers, and activists who have shaped the history of modern Iran, “A Persian Tale of Good and Evil” situates the pieces that follow within this legacy.

Woman, Life, Freedom unfolds in three major sections—“The Events,” “A Bit of History,” and “An Iron Regime … A People Resisting” — each containing several short comics. The majority are written by Iranian political scientist Farid Vahid, French journalist Jean-Pierre Perrin, Iranian-American historian Abbas Milani, or Satrapi, with visuals from more than 17 contributors. These artists, all ages, genders, and speaking different languages, hail from Iran, France, Spain, Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the U.S.

Diversity of style echoes the multiple approaches to narrating the Woman, Life, Freedom movement. Some pieces, particularly when setting the stage early on, read as graphic essays where visual elements depend on Vahid’s analysis or Perrin’s reporting. Elsewhere, language is unnecessary; in the moving “The Art of Rebellion,” Deloupy’s meticulous rendering of a young Iranian woman’s daily activities occurs across silent panels until the final page. Nicolas Wild’s black and white images pairs a newsreel quality with a father introducing his son to the heroism of human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh and Nobel laureate and feminist activist Narges Mohammadi in “Women Saying No.” And Coco’s watercolor aesthetic in “Male Turf” pays homage to Sahar Khodayari, better known as the “Blue Girl,” who self-immolated following a brutal arrest for attending a soccer match.

Woman, Life, Freedom is the result of publisher L’Iconoclaste’s determination “to take tangible action” during the uprising, according to Satrapi’s preface. That statement feels more grounded and less grandiose when thinking about “action” as a range of possibilities advanced by each individual piece. Because comics resist generic categorization and can proffer a deceptively vibrant face even when engaging big questions and issues, they can push against the standard narrative frameworks that quickly come to define a political moment. The narrative strategies gathered in this volume enhance understanding, memorialize, humanize, agitate, shock, terrify, motivate, bolster, guide, and reflect. They satirize to highlight hypocrisy in the day-to-day lives of “Aghazadeh,” children of wealthy, supposedly religious oligarchs (“The Rich Kids of the Regime,” Patricia Bolaños and Vahid), and grieve the dead through imagined conversations between multiple generations of ghostly martyrs (“Dialogue with the Dead,” Paco Roca and Perrin). In giving each contributor the space to create specific and precise storytelling, the project refrains from assigning anyone the impossible responsibility of speaking to all these needs, a surefire way to falter in the face of political upheaval and state violence.

The anthology relies not just on the impact of Satrapi’s previous comic work but on other artists whose creative efforts have broaden the vocabulary of resistance. Amir and Khalil’s 2011 Zahra’s Paradise serialized a fictional account of one family’s efforts to locate their missing son during the Iranian Green Movement of 2009. The project relied on authorial anonymity and online distribution to protect the creators, just as the graphic novel itself documented the protestors’ use of technology to avoid surveillance and connect with other protestors. The filmmaker Jafar Panahi, whose work is referenced directly in this anthology, was imprisoned and banned from directing movies, writing scripts, or leaving in Iran in 2010. His subsequent projects, like This Is Not a Film (2011) and Taxi (2015), play with form to undermine this ban.

Across the Middle East and in the diaspora, Deena Mohammed’s online Qahera comic follows a female superhero who, in short vignettes documenting daily life in her namesake city, stands up to street harassment and misogyny. Qahera is a fantastical counterpart to the real-life heroes and well-organized operations of OpAntiSH, the volunteer collective that joined together to protect female protestors from sexual violence in Tahrir Square. Yasmin Rifae reflects on their strategies and legacy in the extraordinary Radius (2022).

In each of these instances, a singular voice or pair of voices shapes the project and perspective. The more collective nature of Woman, Life, Freedom connects the anthology to comics collaboratives like the Lebanese Samandal, which recognized the value of assembling a range of graphic sensibilities in the mid-2000s. Samandal’s success has also lead to legal challenges and censorship battles, a sobering reminder of the state apparatuses in both Lebanon and Iran surveilling and limiting artistic creation in both Lebanon and Iran; these mechanisms haunt Woman, Life, Freedom, as well.

“A Demonstration in Iran” (Pascal Rabaté and Perrin) hews closest to the practical details of preparing to protest in the face of state violence. Each protective measure — dressing in clothing that allows for quick movement, leaving cell phones at home — is designed to create as much safety as possible for protestors and their compatriots. While Perrin’s youth protestors are practiced, well-trained participants, they still lose a compatriot to arrest by the end of the comic. Though the concluding panel features two protestors looking out from their balcony and vowing to “go again!” tomorrow, the weight of that repetition is clear from the shadowing on their backs.

The young protestors of “A Demonstration” remark that protest is only worth it if video can be uploaded and seen broadly online after the fact; it’s not the only comic interested in who controls political narrative. In Vahid’s “They’re Watching You,” an older Iranian fights against his own information biases and fears to stand alongside his daughter. Illustrated by Mana Neyestani (who has been interviewed and his comics on Kurdish smugglers and Covid-19 in Iran featured in The Markaz Review), the comic unpacks the impact of state television, forced recorded confessions, and disinformation cyber-campaigns on middle class Iranians. The protagonist, Mr. Jafari, comes to understand the regime’s grip on media sources through the influence of his daughter Leila, actively protesting and then arrested in Iran, and a sister who lives abroad and joins protests in Toronto.

Mr. Jafari comes to recognize state mechanisms for chilling protest as his own daughter, Leila, is arrested and forced through a brutal series of interrogations and trials. His fear for her comes from the real accounts of state executions over the course of the protests; “The Winter of Executions,” created by Perrin and the Iranian cartoonist Touka Neyestani (Mana’s brother) memorializes young male protestors killed by the Islamic Republic in December 2022 and January 2023: Mohsen Shekari, 23; Majidreza Rahnavard, 23; Seyyed Mohammed Hosseini, 39; and Mohammed Mehdi Karami, 22. At the bottom of each page documenting the men’s arrest, abuse, and false charges, a sketch of Ayatollah Khamenei descends further and further into a pool of blood.

As the older Mr. Jafari reflects on these executions and others like them, he resolves to fight for his daughter and her compatriots. “Strength lies in numbers,” he discovers. “People must come together, trust one another, and remain unswayed by psychological warfare. For all the Leilas out there, for the generations to come, for the future.”

The emphasis on unity, a population’s power, and a forward looking perspective echo throughout the anthology, perhaps emphasized most notably by Shabnam Adiban’s illustrated rendering of Shervin Hajipour’s revolutionary “Baraye”, which forces readers to decelerate their interaction with the internationally renowned song. Vahid’s introduction to the illustrations note that “Baraye” was played more than 40 million times in its first two days online and garnered international acclaim. Adiban’s visual interpretations ask readers to notice how “Baraye” links the regime’s oppression of citizens with the dispossession of migrants and refugees, impoverished conditions for children, and the degradation of the environment. Adiban’s images nest one inside the next, so that the illustration accompanying “for Valiasr Street and its withered trees” contains a small icon of the newspaper that becomes “for the extinction of our leopards.” In a fight for freedom, these issues are connected to “the girl wishing she was a boy” and “imprisoned intellectuals.”

In that opening essay, Satrapi and Milani call their female historical heroes “small lanterns in a dark night of despotism and misogyny … We can see all roads converging in ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ to lead us toward a promising dawn.” Each comic in this anthology might also function as a small lantern, an opportunity to illuminate yet another aspect of daily Iranian life and resistance under the current regime.

While the lantern imagery is rousing and optimistic, the question that still plagues this anthology is “for whom?” In her preface, Satrapi notes that Woman, Life, Freedom is being made available free of charge online in Persian for all Iranians. Elsewhere, she acknowledges that this book is “more for the Westerner,” in part because of the creative team’s composition: “People in the diaspora — we are not there. We don’t know the heartbeat of our society anymore. We can be the loudspeaker, we can support them, we can talk. Whatever we know, we can spread it. We can share it with the world. But we cannot decide for them.”

The tension of life in diaspora during a moment of political upheaval “at home” threads throughout the anthology. It simmers to the surface in “In the Heart of the Diaspora,” where Vahid and Bee envision an Iranian living in Paris, who observes more connections between Iranians abroad as protests increase. He also feels his own geographic and generational distance from the young people in Iran actively shaping the country’s future. The anthology’s final comic — illustrated by Joann Sfar — gathers project authors Satrapi, Vahid, Perrin, and Milani at L’Iconoclaste’s offices to reflect on their experiences of Iran’s past and hopes for the future. Most usefully, this dialogue reflects lingering disagreement and uncertainty, particularly regarding the role of Iranians living in diaspora. Satrapi “feel[s] for the cause but doesn’t have the legitimacy; after so many years, I can’t say I’m 100 percent Iranian.” Milani argues that “the change must take place in Tehran, but Iran can’t become a democracy without its diaspora,” citing that population’s educational and financial resources. And Vahid complicates the issue still further: “I feel very uncomfortable categorizing Iranians as either those inside or outside the country. There are millions of Iranians living abroad, and I think we’re all Iranians. Don’t forget that a large part of the diaspora goes back and forth, and many often return.”

Woman, Life, Freedom is most successful when it is able to sit with these tensions, to celebrate the art and creativity taking shape within its pages while still acknowledging limitations. The value of collective endeavor lies in the awareness of these discordances, not in the erasing of them. Ultimately, the anthology should engender continued wrestling with critical, foundational questions—what can art accomplish in revolution, and where does it fall short? What is the distinction between bearing witness and voyeurism? And how does a writer or reader reckon with their own positionality even as they participate in collective action?