This week, Lebanon’s grand theatre artist Hanane Hajj Ali is being recognized by The International Committee of The League of Professional Theatre Women. TMR’s Nada Ghosn interviews her below.

The LPTW, an organization that has championed women in the professional theatre for over three decades and headquartered in New York City, presents a week-long virtual presentation of the 2020-21 Gilder/Coigney International Theatre Award Program. Events will take place online from February 16-22, 2021, all at 13:00 EST and will air on LPTW’s YouTube channel.

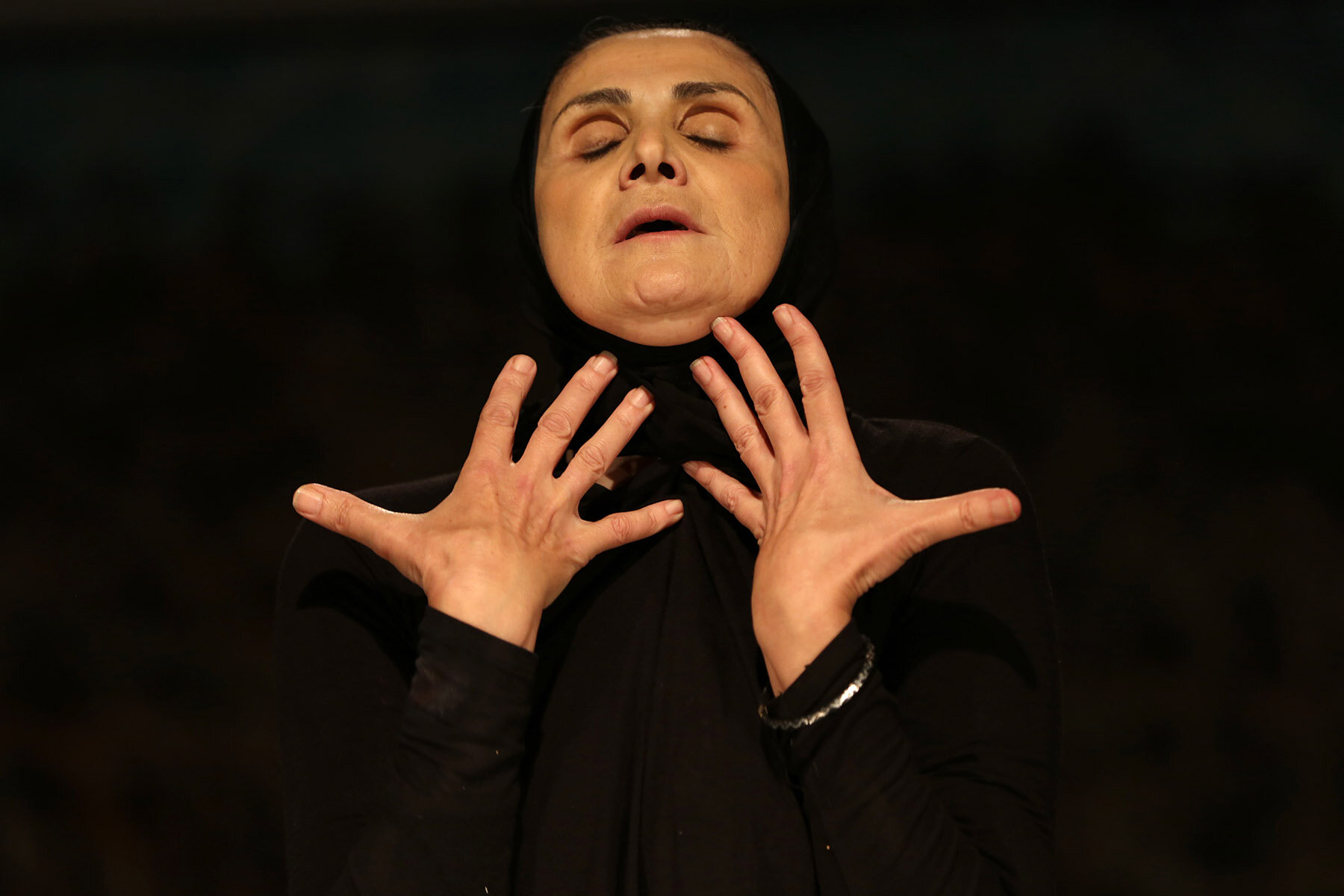

Hanane Hajj Ali was selected from a pool of 27 nominees from 18 different countries. Throughout her 40-year career, she has written, performed and directed acclaimed Arabic-language productions and also facilitated and supported hundreds of colleagues, students and communities in Lebanon and throughout the entire Middle East-North Africa (MENA) region. Jogging: Theatre in Progress, her most recent solo piece, is a “partly autobiographical and taboo-breaking performance that tackles the Bermuda triangle of religion, sex, and politics” which has toured throughout the MENA region and Europe. Recently she was in Switzerland promoting it. Her work is very much about social activism.

The Award itself, hosted by stage, film and TV actor Tamara Tunie, will be presented on Tuesday, Feb. 16. In addition to Ali, the Program honors other artists from countries who are addressing local and global struggles through their theatre practice including political suppression; violence against women and children; racial, gender and identity discrimination; and limited access to education, among other pressing concerns.

Programming includes a Q&A with Hanane Hajj Ali on Wed., Feb. 17, How to Keep Creating While Everything Around You is Falling Apart, moderated by Torange Yeghiazarian. Also featured is a panel discussion, Women on Stage and in the Streets: Three Leading Beiruti Theatremakers, on Thurs., Feb. 18, with Hanane Hajj Ali, Maya Zbib and Lina Abiad, moderated by NYU professor and Lebanese curator Catherine Coray.

Go here to attend virtual events.

Nada Ghosn

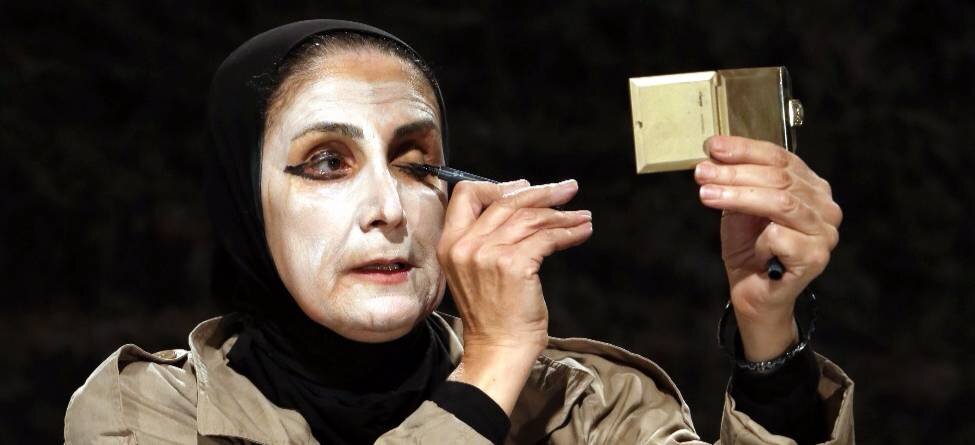

“I’m an actress, that’s the substance; I wear the veil of Muslim women, that’s the form, the outward appearance. Unless it’s the opposite: in substance, a veiled woman, and in form, an actress. A paradox? Contradiction? Fortuitous exception? I believe, for my part, that this is a true situation, not conforming to the usual model, and which poses the complex problem of identity with acuity.”— extract from “Identity Cards”

In her fourth decade as an actress, Hanane Hajj Ali is an eminent figure of the Lebanese cultural and artistic scene. Her career began in 1978 with the Hakawati Theater, which revived the Lebanese tradition of storytelling. In 2005, she was chosen by Jean Baptiste Sastre to play the main role of the mother in Les Paravents/Les Écrans by Jean Genet at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris. Her latest piece, Jogging: Theatre in Progress, won her the Vertebra Award for Best Actress at the Fringe/Edinburgh International Festival in August 2017, and toured prestigious international theatres and festivals.

Previously, she took part in numerous plays, such as Job’s Memory by Elias Khoury (1994), Ah Ya Ghadanfar by Gérard Avedissian (1997), Lucy la femme verticale by Andrée Chedid (2001) and Mrs. Ghada’s Threshold of Pain by Abdullah Al Kafri (2012). She has also appeared in many films, including L’ombre de la ville by Jean Chamoun (1998), La Porte du Soleil by Yousri Nasrallah (2004), What’s Going On? by Jocelyn Saab (2009) and Le jour où j’ai perdu mon ombre by Souda Kaadan (2018).

In her play Jogging: Theatre in Progress, Hanane is an actress who plays a role: that of a woman, a wife, a mother, a citizen and an actress. However, in real life, she is also these five things at the same time. “What I liked in this play is that I was able to play between reality and imagination, between the real character of Hanane (who is not quite identical to myself) and other fictional characters inspired by real characters. It wasn’t easy to be (and not be) myself and these characters at the same time,” she explains.

Her acting style flows back and forth between hakawati and composed characters. Founded in 1977 during the heart of the war by the man who later became her husband, Roger Assaf, the Hakawati theatre works on collective memory and on the assimilation of the forms and techniques of the Arab storyteller, as well as popular poetry.

“This theatrical adventure, instead of projecting myself into fiction or into an aesthetic vision of the world, brings me back to my deepest truth, to my history, to my identity, to all the culture that the human group to which I belong uses as a force of resistance in the face of the war, the destruction, the dispossession of self that all forms of aggression exert on us. ”— extract from “Identity Cards”

“This theatrical adventure, instead of projecting myself into fiction or into an aesthetic vision of the world, brings me back to my deepest truth, to my history, to my identity, to all the culture that the human group to which I belong uses as a force of resistance in the face of the war, the destruction, the dispossession of self that all forms of aggression exert on us. ”— extract from “Identity Cards”Hanane joined the Hakawati troupe in 1978. “I came from politics to the theatre at the age of 16 because of the war. It was a way to fight for citizenship, cultural rights, public space. I discovered, amazed, that the theatre was not what I had learned, but an art linked to people, to life, which draws its material from real-life stories and finds its form in collective expression. It became my vocation,” she says. This theatre dealt with the marginalized, the oppressed, the forgotten, the kidnapped and the arbitrary disappearances during times of war and peace, but also with memory and collective history.

To please her family, Hanane obtained a BA in Biology in 1980, then in 1982 she received a higher degree in theatre studies at the Lebanese University of Beirut. A few years later, in 1986, she left to study theatre and telecommunications in San Diego, California. In 2008, she finally obtained a Master’s Degree in Theatre Studies from Saint Joseph University in Beirut.

“I fought many battles to become ‘Hanane the actress’ in a society that considers actresses to have a bad reputation, to follow in the footsteps of exceptional artists such as Rida Khoury, Renée Dik, Nidal Al-Ashkar, and to be married to an artist of Maronite Christian origin — a struggle shared by few inter-community couples during the Lebanese civil war which, while inflaming sectarianism, also removed the blindfold from the eyes of some who chose unity in diversity. ”— from “Artist’s Manifesto”

As an actress, Hanane first came to writing through her participation in Hakawati. “We would take an idea and improvise, then we would write. Everybody did everything, from costumes, to the stage manager, to directing. I discovered that I could write and that I liked it. It gave me confidence, and I grew that way,” she recalls.

In its original form, Jogging was a monologue about how Hanane runs in Beirut. Then the Lebanese theatre collective Kahraba invited her to the festival “We, the Moon and the Neighbors” organized every year. Hanane turned in a 30-minute performance on a staircase in the street, and a Belgian curator invited her to a residency. From there, other residencies followed and the work continues to evolve.

“Beirut is a part of my life. Two things help me survive: theatre and jogging. When I walk in this city in wild transformation, ideas come to me and I write them down when I get home,” she confides from her Covid-19 confinement. During her exercise outings, she gives free rein to her dreams, desires, hopes, disillusions and she runs, always the same route in Beirut. The effects of this daily routine are contradictory. In fact, two hormones are released in her body during exercise: dopamine and adrenaline, which are in turn destructive and constructive, just like this city that destroys to rebuild, and builds to destroy.

“One day while I was running, I had a dream that was like a spark. I imagined that I was smothering my son with a pillow to relieve him of cancer and this country that had made him sick. After that, I was paralyzed for several days and thought of Medea. I had never accepted to play this role because I was not convinced by her act,” Hanane admits in our phone interview.

“Since then, Medea has lived in me. I have become a fragment of her being and I have been searching for years among the women I meet, the other fragments. I am thinking about how I can approach this myth today. Who is Medea in a worn-out and cunning city like Beirut? If tragedy is a past theatrical genre, why does the smell of horror still haunt my nostrils when I run around Beirut?”— excerpt from “Jogging”

Then Hanane imagines the character of Yvonne, inspired by a news item. On Thursday, October 19, 2019, a woman decides to put an end to the days of her three daughters: Noura, who is 13 years old, Elissa, 10, and Mariam, aged seven, before joining them in death. This educated mother, however, married the man of her life. He lives and works in the Gulf Emirates in the service of a very rich emir. He is in charge of his stables and his purebred Arabian bloods. One fine day, she learns that he has a dissolute life. She prepares a fruit salad that she garnishes with honey and whipped cream, and sprinkles copiously with rat poison before offering it to her daughters. Once they are asleep, she films the scene for her husband, eats the rest of the fruit salad, and goes to bed next to her daughters. Her neighbors discover the bodies the next morning. The film she leaves behind disappears within hours. But one sentence remains: “I left and I took my daughters with me, so that they will never know the suffering that was mine, and to ensure their future.”

“Yvonne wanted to bear witness to something that was close to her heart. The mysterious disappearance of the videotape is proof that she wanted to denounce something, something that no one suspected and that only she knew, something that she could no longer assume, that she was incapable of changing. Something is wrong in this country. Serious incidents shake us and shock us, but pass their way through our memories and fade away as if they never happened. Enormous or imperceptible facts, scandals related to money, honor, politics, religion, family, power, corruption and generalized filth.”— from “Jogging”

The character of Zahra was inspired by a woman from South Lebanon whom Hanane knows. Married very young by her family to a much older man, at the age of 20 she meets another man named Mohamed and decides to divorce her husband. She then becomes a journalist and earns enough money to build their house. But Mohamed changes with time, and she eventually discovers that he loves another woman. She asks for a divorce and becomes a pious woman. She works with the families of the martyrs, and raises her children in this ideology. Two of them die in the Israeli war of 2006, while the third dies in Syria in 2013. Tortured to death by the regime, he is declared a “martyr”. However, he left a letter denouncing this hypocrisy and asked his mother to donate his limbs.

“This story gives my play its full meaning. Even though she didn’t kill him directly, her son died for the ideas she raised him in. Who is Medea? I don’t know. Me? You? Beirut? The dead? How many mothers in Lebanon live in this country without being able to provide a future for their children? It’s exile or death!” says Hanane emphatically.

“no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one chooses refugee

camps or strip searches where

your body is left

aching or prison,

because prison is safer

than a city of fire

no one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying –

leave,

run away from me

now i don’t know what i’ve

become but i know that anywhere

is safer than here”

Excerpt from the poem “Home” by Warsan Shire quoted in Jogging

“My performance is called Jogging: Theatre in Progress because the theatre is an open agora. I close the show with an epilogue where I open a dialogue with people. I’ve never been interested in preaching to the converted; what I’m interested in is stirring up the stagnant waters and stimulating critical thinking,” she adds. This has sometimes led to incidents. “One evening in Dahiye, a man considered that I had no right to attack such sacred subjects as ‘martyrdom’ and pulled out his pistol to threaten me with it. Another time in north Lebanon, women stood up in the middle of the performance to express their indignation at the famous slogan ‘God is dead’, which was bandied about in Beirut during the sixties and seventies, and at the way I challenged Allah by asking Him to give me justice. But these situations have always ended up being resolved through dialogue, managing to open minds and change mentalities. For example, I had to go to these women in the poor areas of the north to talk with them, and we discussed topics they would never have talked about before.”

In this same lineage, Hanane does interventions in the streets of Beirut, a kind of intrusive performance, which are neither political manifestos nor street theater, but something in between. “I take a loudspeaker and I talk. For example, during the confinement, I went around the buildings in my neighborhood with a loudspeaker to call people to share their stories,” she says.

“All my life, I have dreamed of a 360 degree theater, and thanks to the October 2019 revolution, it has come true. The thawra has broken the boundaries between what is theater and what is not theater. Politics entered society with all the debates and performances that took place every day. This is our true right to citizenship, to the city, to culture. People think that the coronavirus has put an end to that, but I don’t think so. Lebanon will never be the same again, just like Egypt, even if it lives today under a totalitarian regime.”

“In my theater and on the street, I seek to break the Bermuda triangle of gender-politics-religion that prevents us from realizing our citizenship. My three characters confront these three taboos, such as the problem of consent between spouses for example,” says Hanane. Moreover, the play was not presented to censorship. At first rejected by all theaters in Lebanon, its international success eventually changed the situation.

“I am yours tonight, I am your wife, your prey. I am your harem, your forbidden and your right… Take me, pierce me, smash me, go through me, tear me apart, burst me and gather me… swell in me and burn in my lair, set yourself ablaze in my womb. All my senses awaken in your honor. I am an immaculate and pure carpet that you turn into rottenness.”— from “Jogging”

“Women have a major role in Lebanon. In cultural institutions, universities, three quarters of the employees are women. They were leaders in the Revolution. But the corrupt political system oppresses them. I agree with the feminists on many points although I never presented myself as such. I think that the whole system is affected, and I have always fought as a citizen, in the name of my right to justice and freedom, although in the context of the patriarchal society, women are more affected.”

Join Our Community

TMR exists thanks to its readers and supporters. By sharing our stories and celebrating cultural pluralism, we aim to counter racism, xenophobia, and exclusion with knowledge, empathy, and artistic expression.

Learn more

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)