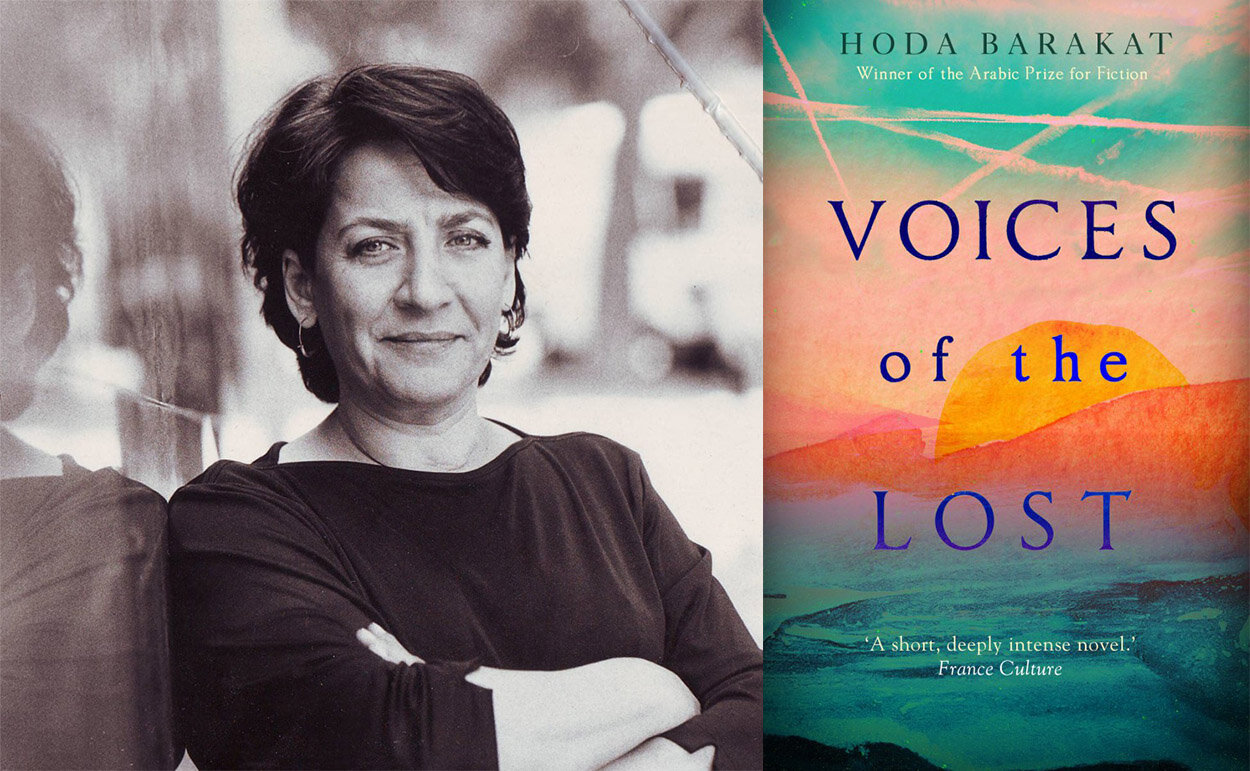

Novelist Hoda Barakat in 2019 when she won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction for Night Mail (Photo: Kheridine Mabrouk) <

<

Voices of the Lost, a novel by Hoda Barakat

translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth

Published by One World (February 2021)

ISBN: 9781786077226

Layla AlAmmar

“Life unleashes its storm on us and we are no more than feathers whirling in hurricane winds.”

A chain of dark confessions animates Lebanese author Hoda Barakat’s sixth novel. Winner of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2019 (under the title Barīd al-layl or Night Mail) and rendered deftly into English by Marilyn Booth (translator of Man Booker International Prize winner Celestial Bodies by Jokha AlHarthi), this narrative traces the anguished stories of men and women exiled to an unnamed country in western Europe.

The novel is split into three parts, which are further subdivided into smaller sections. Part One “Those Who are Lost” (no doubt the inspiration for the peculiar title change) consists of five letters which never reach their intended recipients. These missives are full of recriminations, traumatic memories, loathing, rage and regret. A refugee, abandoned by his mother as a young boy, writes a diatribe of misogyny to the woman he claims to love. A middle-aged woman, waiting in a hotel room, writes of her loneliness to the man she’s waiting for — a Canadian who visited her homeland when she was a girl. Then, a man who suffers from severe PTSD pens a shocking confession to his mother. This is followed by a sister who writes to her brother of how abject poverty drove her to prostitution and then proceeds to unburden her soul of dreadful revelations. Finally, a young homosexual writes to his ailing father of his sorrow and destitution.

“This is not my life, and I don’t know how I slipped into it. I don’t know who pushed me into this night, entangling me in this destiny where I have closed all the doors behind me.”

Many of the characters are unsavory, manipulative, and deceitful. As such, it becomes increasingly difficult to ignore an overriding theme which seems to suggest that all of their abhorrent behavior can be explained away in light of what they’ve been through. Barakat’s goal is clearly to engender empathy, but I confess to reaching the limit of mine on occasion. A personal failing, perhaps. Nevertheless, a sense of urgency prevails which keeps the reader gripped, with the confessions moving from hand to hand until they form a chain of thorny questions, painful admissions, lamentations, and pleas for forgiveness or absolution.

The second part “Those Who are Searching” takes us into the perspectives of some of the intended recipients of these letters: the woman vows revenge against the man who tormented her; the Canadian ruminates on his time in the Arab world while considering whether he should undertake the journey to meet the woman in the hotel room; and the brother vows to kill his sister in order to restore their family honor. The final part “Those Who are Left Behind” is told from the perspective of a postman living in the ruined homeland the characters speak of — if it is, indeed, the same homeland.

What does the novel have to say about the current Arab condition? In fact, one might ask, does it need to say anything? The novel’s ambiguity could be seen as a statement of unity; that whether one is Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian, Iraqi, or from any other war-torn land, the anguish of the soul is the same. The characters communicate the acute and singular agony of having no country, which, as Hisham Matar writes in In The Country of Men, is “a kind of daily death,” where exile becomes “an endless mourning.” Displaced, dislocated, unmoored, the characters repeatedly express a desire to return home, even when they know there’s no home left to return to. Writing of Lebanon specifically, the woman in the second letter counsels against indulging in nostalgia, saying:

“That country is gone now, it is finished, toppled over and shattered like a huge glass vase, leaving only shards scattered across the ground. To attempt to bring any of this back would end only in tragedy. It could produce only a pure, unadulterated grief, an unbearable bitterness. ”

Voices of the Lost is perfectly positioned for an English-speaking audience. The title change is perhaps the most overt way of orienting the novel towards the “West”. The self-congratulatory gesture of the title could potentially alienate Arab readers who might be unable (or unwilling) to read it in the original language. Are Arab women the only ones with “voices” that require unearthing? Do we have a monopoly on the condition of being “lost”? What is this title actually saying about the novel? The original, “Night Mail”, is unique and evocative of the solitary nature of these nocturnal testimonials. As the man in the first letter writes, “You won’t see anything but this night; there’s nothing behind or above or beneath it. This is all there is.” The English title lacks this atmospheric impact.

The transliteration of Arabic words is sparse (inshala, salaam, warta), and vague references to mukhabarat, secret police, and Islamist factions mean that the letters could be referring to any of several Arab nations. There are no complex political dynamics to understand, and gender relations and issues of sexuality fail to reveal anything we haven’t read before. In fact, given what it says about the asylum process as well as the plight of detainees and new immigrants, the novel is more about the refugee crisis than anything else. And with some six million Syrian refugees alone fleeing civil war over the last decade, the fate of such persons is undoubtedly worthy of literary exploration (and it’s one I undertake in my forthcoming novel).

Such experiences and backgrounds are unfamiliar to many citizens of the host countries that refugees reside in… though “host” is a misnomer given the shockingly inhospitable environment faced by a great many asylum seekers across Europe. And so Barakat’s project is a laudable one, even if its execution is at times a bit too didactic. Perhaps the clearest positioning of the book for a “western” audience comes from the Canadian himself. In his letter he wonders:

“How well can we ever know people who have lived through civil wars? How much can we ever really know about the violence and destruction, the losses, the devastation? The overpowering fear they must feel every day? Can we ever really understand how they are transformed, which things change inside them, and which things harden?”

Barakat’s answer seems to be, No, no, we cannot.

<

Hoda Barakat was born in Beirut in 1952. She studied French Literature at the Lebanese University and moved to Paris with her family in 1989. She has published five novels and two plays. Her novels have been translated into several languages and received numerous prestigious prize nominations, including the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature for The Tiller of Waters (2000). In 2015, she was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize. She lives in France.