Deborah Kapchan

Our business is to count the stars, star by star

to chew the wind’s haughty arrogance

and watch the clouds for when they’ll throw us a handful

and if the earth goes far away from us

we’ll say everyone is possessed

everyone has lost their mind

and time, never will its letters fall between our hands

until we write what we are

Driss Mesnaoui 1995:73

Counting the Stars

Zajal: poetry in dialect. There is a long history of the form in oral literature. Poets in marketplaces and public squares, storytellers recounting epics in verses those around them can understand. As any Arab will tell you, Moroccan Arabic is about as far from Modern Standard as one can get, infused as it is with syntax and vocabulary from Tamazight, the language of the authocthonous Amazighin of North Africa, and spiced with Spanish and French. And yet, the movement for writing in Moroccan Arabic, or Darija, began decades ago. The mother tongue yields secrets that classical Arabic never will. It is about emotional resonance. The problem, however, is one of translatability, of reaching into the cultural depths of the genre, not only in its oral form, but now in its written incarnations. Zajal often remains local and its poets, though prolific, are rarely known outside of Morocco.

I encountered two prominent Darija poets in 1995.

Ahmed Lemsyeh and I met in Rabat. At that time, Lemsyeh was a schoolteacher and an activist in the Ichtiraki socialist party. More than that, he was already one of Morocco’s finest poets, who often published his work in chapbooks and in one of the daily newspapers, Al Ittihad Al Ichtiraki. Lemsyeh’s was the first diwan, or poetry collection, published in Darija.

I had come on a Fulbright to study Moroccan performance traditions. After independence in 1956, Moroccan artists wanted to define an authentic Moroccan theatre. Tired of performing Molière in French and Shakespeare in Arabic, they turned to the halqa, an old form of Moroccan entertainment, combining storytelling with satire. Literally meaning a link in a chain, the halqa is a circle of people with a performer in the center, an interactive space of humor and a demonstration of verbal and gestural acuity, performed in Moroccan dialect, Darija. My first book was an ethnography of these performances in the Moroccan marketplace, including the emergent voices of women. I had read the treatises on the halqa by theorist Abdelkrim Berrechid and playwright Tayyeb Saddiqi. I had read the works of Juan Goytisolo, the Spanish expatriate writer living in Marrakech who evoked these scenes. I came to Rabat to attend the plays wherein the trope of the halqa was employed.

In 1995, however, Mohammed the Fifth Theater was closed for repairs. Or for something. Was this about censorship? In Morocco, as in many countries in the Middle East and North Africa, the critique is often hidden in symbols and in stories that take place in another time. Moroccan theater in dialect was one forum for this social critique. It was bawdy and virtuosic. But although the main theater was closed, there was a small annex in the back that remained open. And there, on my way home from Rabat’s Kalila and Dimna bookstore one late afternoon, I stumbled through the open door into a performance of zajal. The audience was ohhhing and ahhiing, enrapt with the words, and sending up affirmations like “allah!” as if at a musical concert. I did not understand everything I was hearing, but I waited until the performance was over, then introduced myself to the poet, Ahmed Lemsyeh. And so a friendship, and a project was born.

Lemsyeh was very articulate about why it was necessary to write in the mother tongue. It held the secrets of culture, he said. While American anthropologists thought the word “culture” made sweeping, damaging generalizations, Moroccan poets and artists sought to make it as salient as possible. The metaphorical density of Darija resonated differently than classical Arabic. Would an Italian write poems in Latin?

Lemsyeh drew his material from old sources like Sidi Abderrahman al-Majdub, a Moroccan Sufi mystic. Al-Majdub was still cited in the halqa centuries later. Lemsyeh didn’t quote his quatrains directly but made allusions in such a way as to revive the auditor’s memories of childhood, while creating something entirely new. He was a master craftsman of words. Listening to him, audiences would swoon.

I had already been initiated into the genre of al-malhun — sung poetry from the 14th century, also in Darija. My friend El Houcine Aggour, my roommate’s boyfriend in Beni Mellal, had listened to it nonstop when we were all living together in 1982. After preparing a sumptuous tajine or couscous for us, he would put on a tape of El Hadj Toulali singing a song about al-dablij, “a bracelet” that a suitor bought for his beloved and then lost. We learned Arabic this way, through listening to a Moroccan genre.

“We are having a reading in the park downtown on Thursday,” Lemsyeh told me. “Come. I will introduce you to the other zajalin.”

When Thursday arrived, I walked to the park shortly after the afternoon call to prayer. There was a seashell stage. People were beginning to congregate, men and women, many students, and other lovers of words. Lemsyeh greeted me. “I’m about to go on. I’ll speak to you later,” he said, and took the stage.

Lemsyeh read from his most recent publication, Shkyn tarz al-ma? (Who Embroidered the Water?)

Time sneezed

And space expanded

A ray of sun swelled

And sleep shortened

The skein got tangled and I couldn’t find the tip of the string

Listen to Ahmed Lemsyeh reading excerpts from “Watching the Soul”:

Lemsyeh read on, encouraged by the thrall of the audience. “Give me your attention,” he said, “and use my words…Make a difference between the slaughterer and those who just bark. Silence has become their weapon.” This was social critique and a call to arms. He drew upon imagery from the bled — the Moroccan interior; skeins and looms and weaving. He used idioms not found in classical Arabic – like “listening to the bones.” He talked about as-sirr, the secret, a reference to Sufism.

When Lemsyeh was finished, another poet took the stage. He was with his young son. They read together, the father’s voice commanding, the son an apprentice. This was Driss Mesnaoui and his eldest child, Nafiss. Mesnaoui also read from his recent publication, entitled with one letter: waw [و ]. In Arabic literature this character is used like a punctuation mark, meaning “and.” /و/ signals both the end of one thought and the beginning of the next. It is the word that connects. And this is the reason, he told me later, that he entitled his diwan this way. In Sufism, he said, /و/ is also the breath. When joined with the letter ha — /هو / — it means He or God. Huwa hu, the Sufis chant. He is He, or in esoteric translation, I am that I am. (Huwa hu huwa hu huwa hu huwa hu. I myself would be chanting this with a group of Sufi women in Casablanca not long after our conversation.)

Mesnaoui was not only a mystic, he was also a social historian and critic. That day he read a poem about the Rif uprising, the colonial war between the Spanish and the autochthonous Amazigh of the Rif mountains from 1911-1927. The Moroccans were led by Abdelkarim al-Khattabi, a guerilla who spoke Tariffit (the northern Amazigh language) and Spanish. He resisted occupation and his army was successful for many years, until the French joined with the Spanish and used chemical weapons to defeat the rebellion: “The crowd drank us before we entered the city/ worry we wore it/ as we wore the wounds of the swords of deceit.” His voice resounded across the park.

those who needed a boat became, themselves, a ship

those who gave birth to us

hunger ate them before they could eat

those who raised us

the grave swallowed them before they could dig

we found fasting the medicine for hunger

our thirst drank our tears

Listen to Driss Mesnaoui:

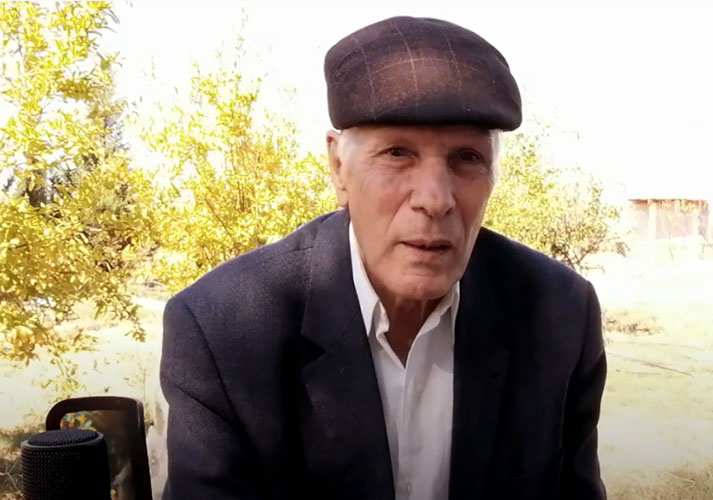

The audience was captivated and I understood why. He spoke with passion and presence. Like Lemsyeh, he was an attractive man, perhaps in his mid to late forties, just a bit older than me at the time. He had a gravitas about him, but was also warm and humble. The message was historical but had clear contemporary resonance.

There was a chill in the air, the sun was beginning to set, and the reading ended. Lemsyeh came over to me. “I want to introduce you to Si Driss,” he said. We both walked over to where Mesnaoui and his son were standing.

“This is Deborah,” Lemsyeh said. “She is an American professor doing research on zajal.”

Mesnaoui greeted me warmly. “Perhaps we can get together sometime soon,” I suggested.

“With pleasure,” he answered in Darija. “Here is my number.” Mesnaoui wrote it on the bottom of a handwritten poem and handed it to me.

“I’ll give you a call soon,” I promised. And he and Nafiss were off.

Lemsyeh and I walked past the Mohamed V Theater, up the hill toward Place Petri and entered his apartment. There were already several people there, sitting in a large living room on banquettes. Lemsyeh introduced me to his wife, Amina. She was a politician with a seat in the Moroccan parliament — one of the only women in higher office at the time. Like Lemsyeh, who insisted I call him Ahmed, she was in the socialist party. She was preparing to go to Beijing for the World Conference on Women as their representative.

“Marhaba,” she welcomed me. “Sit down. We’ll talk later,” and she went back to the kitchen to supervise the women preparing the food.

Writers of many genres were there that night: novelists, journalists and public intellectuals. They all belonged to the Moroccan Writer’s Union. Ahmed was careful to introduce me to the zajalin — the poets writing in dialect. I met Mourad El Kadiri, the future president of the Moroccan House of Poetry. Although most of the guests were men, among the four women was Wafaa Lamrani, a woman of great beauty and charm, who wrote passionately about love in classical Arabic. She was the sensation in the writing world that year, and the dinner was largely to celebrate the publication of her recent book, Ready for You. Wafaa invited me to a reading she was giving in Tangier and I accepted, despite the fact that it was six hours away by train.

Ahmed came over. “La bas? Everything all right? Did you get something to eat? You know I wish Si Driss would join us…”

“He’s a very talented poet,” I said.

“He is,” Ahmed echoed. “And he stays clear of politics.”

I understood then that the lines between the Moroccan Writer’s Union and the socialist party were thin.

I went to see Driss Mesnaoui soon after, taking a taxi across the bridge and into Salé. Mesnaoui lived in one of many similar-looking buildings in a new development on the outskirts of town. It was a hot afternoon. The taxi driver had to circle around the unpaved streets looking for his building, raising thick dust in the air around us. We finally found it. There was no buzzer, so I trudged up four floors to what I hoped was the right apartment.

His wife Saida welcomed me with such profusive warmth that I immediately felt like an old friend. Their place was humble but clean, with an upright piano in the living room. Saida made tea, serving it with the kind of Moroccan sweets I find irresistible: marzipan gazelle horns, peanut butter drops, and rich butter cookies. “All made at home,” she assured me. But these sweets were only meant to open the appetite for the meal that followed.

I told Driss that I was trained in thaqafa shafawiyya, oral culture, and that I had written about the halqa. Like most people, he was delighted I took such a deep interest in his culture, and complimented me on my level of Arabic. He told me he was a schoolteacher from a rural village on the way to Meknes. His parents had a farm there.

His son Nafiss joined us for the meal, along with his younger brother Amine who was the pianist. After a green pea, artichoke, and lamb tagine, Amine played a Chopin sonata. He was ten years old and his playing was impressive.

Mesnaoui told me why he wrote in Darija. Like Lemsyeh, he felt it expressed what classical Arabic could not. It resonated more deeply. “The problem is,” he said, “In Morocco, literacy is still not what it should be. People read newspapers perhaps, but literature…” he shook his head. “It’s a big problem here.”

I told him about the literacy project that I had worked on in both El Ksiba and Marrakech, about the tests we’d administered to the children once a year, the interviews with their parents I’d done. “It seems to be getting a little better.” [1]

“Yes, shwia b-shwia al-haja mqdiya, little by little things get done,” he said, reciting a Moroccan proverb. “Still, people read newspapers, but not much else.”

“Do you also publish your poems in the newspaper?” I asked. Lemsyeh’s poems were often there.

“I don’t,” he said. “I don’t belong to a party. I like to keep my independence. The newspapers only publish their own.”

There were several newspapers on the stands each morning — one socialist, one communist, and several royalist. Moroccans knew the affiliations of each one. Some bought copies of all of them, to get a fuller picture. Lemsyeh was a socialist, and a vocal one at that. As I noted earlier, his poems in Darija were often in Al Ittihad Al Ichtiraki. Mesnaoui quickly changed the subject and looked at me with warmth in his eyes: “Nhar kabir hada! This is a big day,” he proclaimed. Moroccans say this when they are in the presence of an honored guest. As the junior scholar at this gathering, I blushed. “Nhar kabir liya ana,” I insisted. “It’s a big day for me.”

Mesnaoui then asked Nafiss to read us one of his own Darija poems and he obliged, standing in front of the table. He read a short verse by heart, with confidence and conviction. He was clearly a poet-in-training.

“Qasm-nah taam, we’ve broken bread,” Mesnaoui said as I was leaving. “We’re friends. We need to see each other more often.”

“Aji aand-nah bzaf, come to us often.” Saida said. “Marhababik, you’re always welcome.”

The next day I went to a bookstore specializing in Arabic literature. It was on Avenue Moulay Abdellah next to the Septième Art Cinéma.

“I’m looking for zajal,” I said.

“It’s in the poetry section,” the seller replied, walking with me to the back.

I took books by Lemsyeh and Mesnaoui off the shelves, as well as one by El Kadiri — all writers in dialect. Then I perused the section of classical Arabic for Wafaa Lamrani’s oeuvre. One of her books was sealed in plastic wrapping. I’d understand why when I got home: it was illustrated with erotic drawings by the Moroccan artist Mohamed Melehi. There were sexual politics in these publications as well. I left with so many books I could hardly carry them home. This was the beginning of a twenty-five year project translating Moroccan poetry into English.

In his volume entitled La Poésie Marocaine: de l’Independence à Nos Jours, Abdellatif Laâbi posits that languages themselves may contain a “hard nut of identity” (un noyau dur d’identité) and asks if it is “possible, or even legitimate, to crack this nut.” In my work, I do not attempt to pry open what resists translation so much as to infuse its materiality into English verse, to render the smells and tastes of Moroccan poetry for an Anglophone audience. Translating poetry is entering into the mind of another’s being, meditations and despair. Insofar as poetry is a repository for a collective spirit (not that it always is), translating poetry is also discerning a substrate of social ontologies, ways of being accrued over centuries. While romanticizing a national spirit may lead to the grossest of fascisms, it is nonetheless possible to speak of what Deleuze and Guattari call a milieu — the vibrations of a territory, formed by the stories that have lived there, as well as the songs, languages, and other practices embedded in its history.

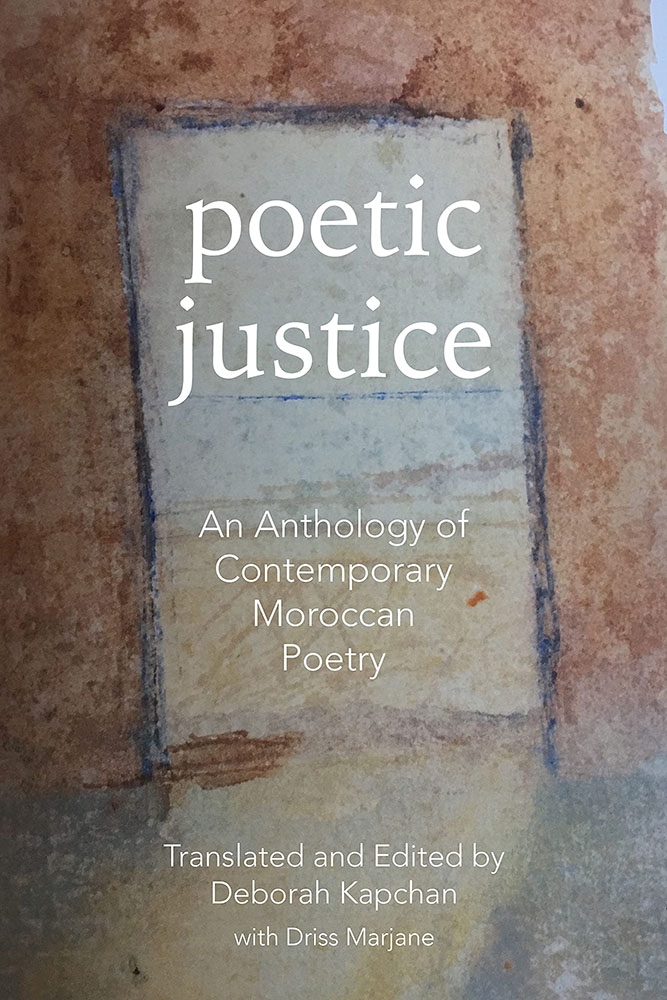

Poetic Justice: An Anthology of Contemporary Moroccan Poetry was published 26 years after my first encounters with Lemsyeh and Mesnaoui. Of course much has changed in the Moroccan literary world since then. New poets are on the scene. But Lemsyeh and Mesnaoui continue to publish prolifically. They are the doyens of poetry in Darija.

The pandemic as well as the exigencies of life have intervened in recent years and prevented my yearly visits to Morocco. The last time I saw Ahmed Lemsyeh, it was around his dinner table with his wife Amina. I had been there many, many times before, partaking of their hospitality and watching their children, and now grandchildren grow up. He had just published his 25th book, and was busy collaborating on a YouTube performance of music and his recited poetry.

I also visited Driss Mesnaoui that year on his farm outside Meknes, where he and Saida have retired. We ate on their terrace, surrounded by fruits trees and rows of leafy vegetables, drinking fliu, fresh spearmint tea from their garden. In his last letter he told me about his recent publications, the conferences he’s been attending on zajal, and the dissertations that students are now writing about the movement to write in dialect. ما قدمته لي شخصيا عمري ما ننساه . أنا واشمُه في قلبي قبل ما كتبته في مذكراتي, he said to me, “I will never forget what you’ve given me. I smell it in my heart before I write it in my notebook.”

Dear Driss, dear Ahmed, I feel the same. The “letters of time” have fallen into your hands and mine, as we write what we are, translating love and poetry through the decades.

[1] Wagner, Daniel A 1994. Literacy, Culture and Development: Becoming Literate in Morocco. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guardian of the Soul

Ahmed Lemsyeh

Wind, the veins in a glass

a shackled wave

and a flute in my head

The soul surrounds all the senses

it’s a sea where people hide

a pillow on which the head rests

clothes, a cane,

a door in the water without a guard

a key that opens the stubborn lock

And I crawl, escaping

undecided between a body that drips down a glass

And a glass that pulses with feeling

the soul

ornaments its walls with obscurity

pregnant with shadows of glass

stabbed with a dagger of light

sleepy

the air its veil

its charms spin words

that the secret conceals

a long cry muffled like the night

planted in the skin

the eye reads the talking gaze

And the pen begins to stretch

above the heart

covering and expanding

I saw the hidden become visible [2]

I fear madness will reappear

If it wakes, where will I put it to sleep?

If it comes back to life, where will I bury it?

If it balks where will I shelter it?

If it goes into a trance, where will I calm it?

I saw death covering its face

mounting a black stallion

It tied its horse to a palm tree

and ants

began to move in my ribs

I became a bee

my breath the sea

my mouth amber

I drink the soul’s guardian

and snack on an ant

knead the body and put it on the bread board

My voice is an oven

Compared to it, life is worth an onion

And we, to death, are fated [3]

We wait for it to turn its back on the qibla

They say life will come back in a piece of wood

planted on the mountain top

and the whole world a sea

They say the thread of death is in the reed

that life delivers

Every death renews age

The wind is soap that sings

and the trees mute town criers

Light rays, a crooked finger

the remaining words aren’t sleeping

The morning repents

Suffering is hot and about to lay its egg [4]

And death is chaste, taking only its due

Time turns around

but life has not had its menses

Those who abandoned it so desired it

Everyone forgets death in diversion

And we live day to day

He who denies and wants to live forever

will see his face in the clouds

The axis is not the motor of life [5]

The mill is not the battery

The secret is fearing death

It’s the oil that ignites life’s candle.

[2] al-ghabir dhahir, “the absent became visible”

[3] al-mut haqq ‘ali-na. Death is our destiny.

[4] Hamiya fi-ha al-bayda, warm and has to lay an egg ; making a noise like a chicken about to lay

[5] in French in the original

Part of a Country Symphony

Driss Amghrar Mesnaoui

the crowd drank us before we entered the city

worry we wore it

and we wore the wounds of the swords of deceit

those you needed a boat became themselves a ship

those who gave birth to us

hunger ate them before they could eat

those who raised us

the grave swallowed them before they could dig it

We found fasting the medicine for hunger

our thirst drank our tears

the tears sprouted wings

they flew away

they wandered

far away from myself

and close to the sea

they brought me down

I drank a handful from a wave of chaos

drowning like the sun before it sets

in a sea of wars

the bands of forgetfulness swallowed me

the heels of the wind threw me in the mill

the days chewed me up

am I a person?

In my chest is an amber eaten by ashes

on my shoulder is a tree where crickets play

am I a person?

I’m the forgetful one…I am the drowned

I’m the inattentive one…I am the awakened

I put out my neck to help the drowning

hope, my eyes and arms

I extend my hand to sew the patch of star

rising from the bottom of the dirty night

I sew my skin to the bones of the flayed day

with saliva I wash the face of cheated luck

hope, my eyes and arms

I said that it just may be that the buried root will live again

I said it just may be that arms and tongues will sprout from the clay

I dug in my brain, in my veins

I looked in the seas, in my worries, in my blood

for myself

for just a bit of myself

I found Abdelkrim Khatabi rising like a giant

from a vicious circle of cares

he split the ground…he split the seed

and he came down on the notebooks

he opened his hands and said, “here’s the qibla”

with me in me

a new thirst inhabited me

like the flower’s thirst for a drop of water

my thirst can be quenched only for that red star

I ran behind the dewdrops of night…behind the star

I found Abdelkrim in the spring of water…in the roots of the tree

I found him harvested yet planted

I found him in the vapors, in the clouds, in the waves

I found him, ink, paper, feather, wings, bird

I am intrigued by this article. I am a Ph.D. with social anthology and bilingual education background. I am also a perfumer who tells cultural heritage stories through scent. I do this based on a respect for tradition, as well as bold innovation.

I will be in Ouarzazate and the Dades and Draa Valleys in the fall 2023. I will read contemporary Moroccan poetry and history before going. My goal is to explore how Moroccan poetry may be translated into scent.

I am curious if anyone has thoughts on this project.

Eshte nje mendim qe respektomtraditen