Our literary editor takes us on a deluxe reader's tour of the stories behind the stories in the double summer fiction issue for 2024.

There’s a long-standing tradition that the dog days of summer are meant for reading.

For months now, newspapers and websites around the world have been publishing their fiction lists so that people can order books to take on holiday or to the beach. The Middle East is a little different. In notoriously hot countries any season is prime reading time. Over the last few years the popularity of book bloggers and influencers has grown in bounds in the Arab world. And that attests to the fact that readers don’t need vacations as an excuse to hunker down with a book. Publishers in the region may be beset with problems, particularly in terms of distribution, but they still provide homes for a plethora of new voices and experiences.

Interestingly a new generation of translators, both in the East and West, has brought SWANA fiction and memoir into English translation. It is this movement of new short fiction and memoir from the region that The Markaz Review champions in its annual summer double literary issue.

The stories from Oman’s leading writers show particular sensitivity and edginess. “A Blind Window on Childhood” by Hamoud Saud and “Besara” by Huda Hamed, both translated by Zia Ahmed, address issues that are rarely discussed. Saud often includes a blind figure in his fiction, and the same is true of this short story. In it, a blind grandfather quizzes his grandson on what he sees, and the two of them visualize beyond the physical world. “Besara” is an excerpt from Hamed’s novel Alashiyaa Laisat Fee Amakinha [Things Are Not in Their Place]. It is a coming of age story of a young besara woman.

Unfamiliar with the word, I asked Ahmed to explain it, and he added this translation note to Hamed’s excerpt: “Besar (female form besara, plural beyasir) is a person whose ancestors were outside the tribal system as indentured servants of uncertain lineage, or otherwise marginalized in society. Slavery existed in Oman from antiquity until the 1970s, and the beyasir were in many ways better off than the enslaved. However in other ways, they fared worse, since the enslaved carried the tribal name and could count on the tribe to protect them; the beyasir could only count on themselves.”

Ahmed, an American writer and diplomat living in Muscat, is immersed in the country’s fiction. I asked him why? He answered by email: “Oman and its literature drew the world’s attention when Jokha Alharthi won the International Booker in 2019, but Omani authors have been writing thoughtful, provocative fiction for years. As a foreigner in Oman, I was particularly intrigued by the diversity of creative narrative forms that blur the boundaries between memoir, history, and fable. [It almost] feels as if an inconspicuous country on the margins of the Arab world had produced the likes of Alice Munro and Jorge Luis Borges in one generation. So I read and — frustrated by my inability to convey to my bibliophilic partner the depth of my obsession — began to translate, with patient help from Huda Hamed and Hamoud Saud, two exceptionally gifted writers from different ends of Oman’s lush literary landscape.”

Unsatisfactory marital relations and difficult family life have long been the bedrock of compelling fiction, no matter an author’s language or ethnicity. The following short stories, each from a different country, convey upheaval in myriad guises, some as the result of migration to another country, others from spending too much time in virtual reality, or even joining a cult.

“The Lakshmi of Suburbia,” by Natasha Tynes, reveals the allure of an internet influencer on a woman who moved from Jordan to the US and “remakes” herself in a failing marriage. In the botanical short story “An Inherited Offence” by Nektaria Anastasiadou from Greece, the fate of the terebinth (or turpentine) tree, one that requires both female and male trees for pollination, foreshadows the misogyny at the heart of a Levantine family. In Kabul, cool Gen Z on Instagram and FB clash with traditional Afghan values in “The Social Media Kids” by Qais Akbar Omar.

Meanwhile in Nora Nagi’s subtly told short story, “Certainty,” an Egyptian woman who finds herself in Seoul, South Korea, with her better-educated husband, rises to the challenge of modernity, while he remains mired in tradition.

A frequent contributor to The Markaz Review’s fiction pages has been MK Harb, from Lebanon. His humorous short stories about life in Beirut are usually told from the point of view of a group of reoccurring characters, Malek, his friends and family. In the short story, “We Danced,” Malek and Careema join a pseudo-psychotherapy group.

In a region riven by conflict, some short fiction in the issue portrays a possibly despicable political character as someone to pity. The protagonist in Odai Al Zoubi’s stream of conscious short story “Ten-Armed Gods,” translated by Ziad Dallal, is stuck in the horrors of waiting. He is a minister in the Syrian regime and there are only two outcomes for those who stray from the Ba’athist Party — torture in prison or death. The story unfolds in a rigid, unending block of words, with no paragraphing. Thoughts about the minister’s mistress flit in and out of his musings on his political rise and fall. In Mohamed Farag’s “Keeping Up,” translated by Nada Faris, a man finds himself lost in a Kafkaesque labyrinth of Egyptian officialdom.

From these oppressive continual presents we also encounter flashbacks to the past, as in the compelling short story, “Madame Djouzi” by Algerian author and cultural critic Salah Badis, translated by Saliha Haddad. Using a poignant metaphor, the tale describes a photograph of Che Guevera falling off the wall in a once lavish house that witnessed the heady days of liberation struggles from Cuba to Algeria and South Africa.

“The Mulberry Tree” by Mohammed Alnaas is the first chapter of Alnaas’ satiric novella, Alerak Fe Jahannam (Altercation in Jahannam). In the excerpt, translated into English by The Markaz Review’s managing editor Rana Asfour, the village in question bears the name for “Hell” in Arabic. A local conflict develops there after a fight breaks out between a haji and a Chad war veteran – all over a badly brewed bottle of homemade hooch, bukha.

Rana Asfour has translated several pieces of Alnaas’ writing into English. She explains by email that he is a writer to whom she likes to return.

“When the Gaddafi regime fell in 2011, many Libyan writers felt it was safe to finally be able to bring forth their works — which is something they had not been able to do before because of the suppression of ideas from the controlling state. One of these emerging young writers is Mohammed Alnaas who, with each new work, be it a short story or novel, breaks down taboos, and challenges society’s status quo by tackling themes like masculinity, gender roles, sexuality, women’s role in society, the absurdity of conflict, and public corruption among others.

“With each of his works I learn a little more about Libyan culture, form of address, society, and the nuances of language. At times, it feels like I’m learning a new language altogether, despite the fact that what I’m translating is formal Arabic. But he intersperses this with local dialogue that brings that extra bit of excitement and challenge into the translation. And that’s another thing I like about working with Alnaas’ pieces: he’s always open to dialogue regarding his translations and there’s always something useful I’ll garner from those interactions.”

Another first chapter published in our double summer issue comes from Karoline Kamel’s Victoria, a popular novel from Egypt translated by Ranya Abdelrahman, it was shortlisted for the 2024 Sawiris Best Novel Award for emerging writers. In the first chapter Kamel depicts a sickly mother who takes her daughter to the seamstress to get new galabeyas made in preparation for what might be their last family holiday together.

South America might lie thousands of miles away from the Middle East and North Africa; yet there is an overlap of literary techniques and approach between the two areas. For young South Americans, the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez has given way to the subgenre narrativa de lo inusual [narrative of the unusual]. Still, the venerated Colombian winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize for Literature casts a long shadow over Alireza Iranmehr’s short story, “Firefly,” translated from the Persian by Salar Abdoh. One might imagine the lives of conscripts in the Iranian army as a serious matter. However, Iranmehr’s irreverent tale about a fellow nicknamed “Djinn,” who’s always going AWOL, also has echoes of Joseph Heller’s Catch 22.

Horror, of the allegorical nature, permeates the short story “The Doll with the Purple Scarf,” by Iraqi novelist Diaa Jabaili, translated by Chip Rossetti. After conquering Mosul, ISIS declared war on dolls, and Barbies and inflatable sex dolls, among others, await their fate in a warehouse. In “Frida Kahlo’s Mustache” by Abdullah Nasser, translated by the Markaz’s senior editor Lina Mounzer, a couple’s yearning for a baby somehow invokes a strange biological transformation. From Márquez to Kahlo and the Mexican writer Nicolás Medina Mora, who briefly appears at the beginning of Salah Badis’ “Madame Djouzi,” one could suggest that the cultural influences of Central and South America have become important touchstones for MENA writers.

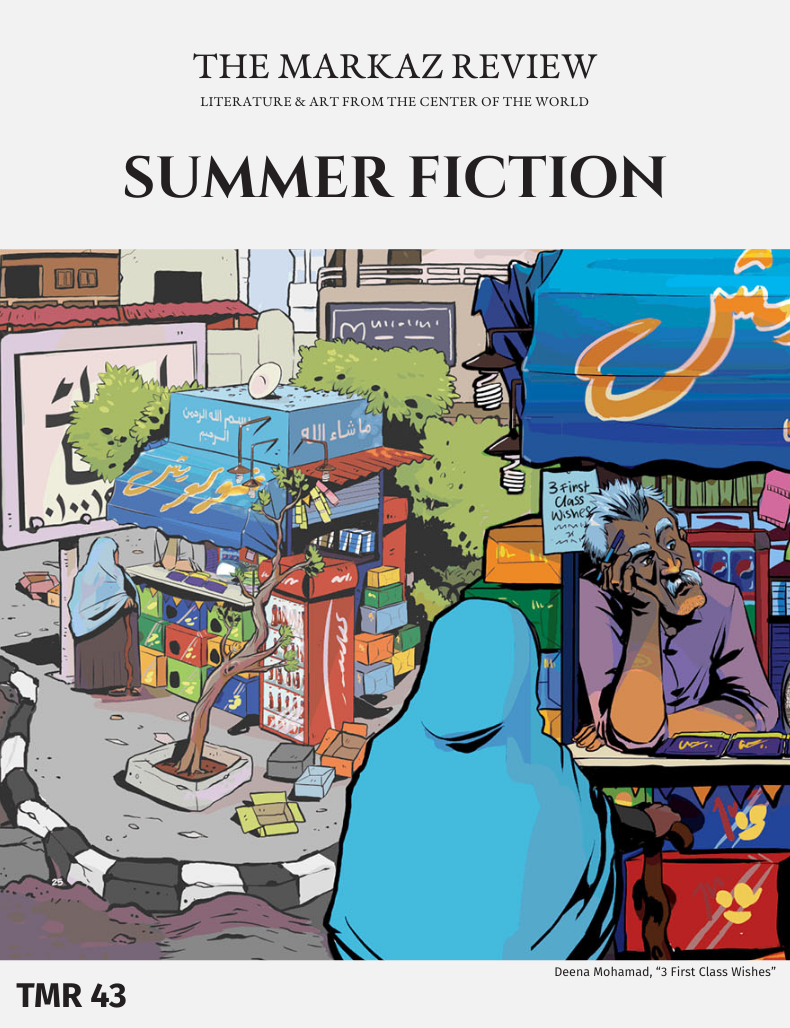

The graphic novel is another popular form that has taken root in the Middle East. This issue’s featured artist, Deena Mohamed, is an Egyptian comics practitioner, writer, designer, and author of the fantasy Shubeik Lubeik [Your Wish Is My Command]. Katie Logan, who interviewed Mohamed, has also contributed a review of Persepolis’s Marjane Satrapi’s graphic compendium, Woman, Life, Freedom, which features a cadre of graphic artists from around the world.

Remaining with that revolution, in Iran, Nika Shakarami was one of the early demonstrators murdered by the Iranian regime during the 2022 women’s protests. The mystery surrounding her death — the regime said it was suicide — upended the 16 year old’s family. Poupeh Missaghi translated the mourning diaries of Nika’s aunt, Atash Shakarami, who was jailed and forced to give a televised false confession after she disputed the government’s claims in public and online. In the issue, Missaghi writes about Atash’s diaries: “Her writings … provide a complex, double-layered narrative, first, of Nika’s life as a victim of regime brutality, and second, of Atash’s own life as a survivor of state horror. It is an interwoven biography of two Iranian women, related by blood, from two different generations, each fearlessly standing against a totalitarian regime in their own way.”

For Atash Shakarami, writing is an act of resistance and so is reading. This theme resonates throughout the short stories and flash fiction by the issue’s younger writers. Haidar Al Ghazali, 20 years old, writes from Gaza. His debut short story in English, “Deferred Sorrow,” given to the Markaz by PalFest and translated by Rana Asfour, is about the shocking choices a father is forced into making on the frontline of a seemingly never-ending conflict. Seventeen-year-old Stanko Uyi Sršen wrote “The Cockroaches” in Zagreb, Croatia, for a school assignment. Its subject of gay love during the war on Gaza is reminiscent of the heartfelt entries written by Palestinians on the groundbreaking, geo-location website, Queering the Map.

The memoir included in our double summer literary issue may also strike the reader as something unexpected. Lina Mounzer has translated an excerpt from Fawzi Zabyan’s Memoirs of a Lebanese Policeman, which she describes as: “a rare — both literary and cynically funny — look into the internal workings of the Lebanese security apparatus, it is also a historical document of a tumultuous time, detailing the political functioning of the country during the Syrian military occupation and in the aftermath of their ousting [in 2005].”

Sometimes life can be stranger than fiction. While studying Arabic in Cairo, Bel Parker became a butcher’s assistant in a small historic quarter of the city. Her experiences of halal butchering, and the welcome she received from the surrounding community in the predominately male profession, make for fascinating reading. That she was largely accepted is particularly notable, given traditional Islamic beliefs against the practice of women being involved in the slaughtering of animals.

Writers have always had their inspirational mentors. For Tarek Abi Samra, Flaubert has been a difficult taskmaster — in his wry essay “Flaubert’s Poison Pen,” translated by Lina Mounzer, the Lebanese writer imagines himself sitting at his computer with the 19th century French novelist watching over his shoulder and making these pronouncements: “This word is not ‘exact’; find another. That word appears twice on the same page: replace it with a synonym. That alliteration is an abomination to the ears. This expression is the worst sort of cliché, the sentence is clunky, the whole paragraph doesn’t hold together and has no organic connection to the one that follows … Frankly, I don’t know if what you’re writing is even worth revising.”

Despite imaginary Flauberts or other inner, destructive voices perpetually intervening, it takes writers time to trust themselves and the stories they feel the need to tell. Each short story, memoir, diary and essay is an act of self-creation or love. Like wonders or small miracles.

Reading is for all and any time of the year — not just for the summer.

It is always a thrill to receive a new edition of The Markaz Review with it’s rich diversity of world class literature written in Arabic, which in my ignorance, I cannot read in the original Arabic language. Thank you so much. You and your translators do very valuable work indeed. Many thanks to you all. Very Sincerely, Robert Cole.