The Leash and The Ball, a novel by Rodaan Al Galidi

World Editions 2022

ISBN 9781912987320

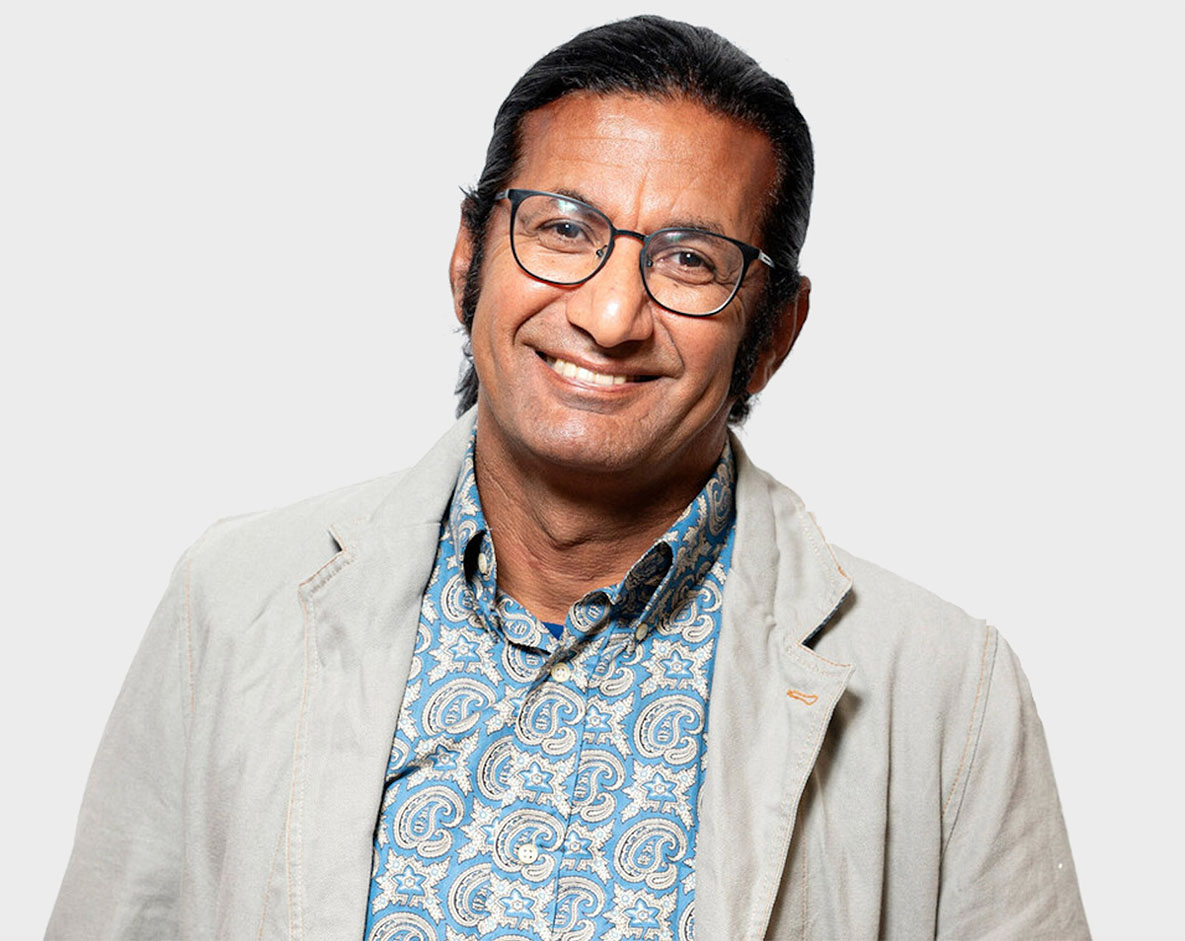

Rana Asfour

Dutch Iraqi Rodaan Al Galidi’s latest novel, The Leash and The Ball, released in the UK this month, picks up where his 2019 novel Two Blankets, Three Sheets, a fictionalized account of his immigration experience, left off. Samir the Iraqi asylum seeker, based very loosely on Galidi, has finally been granted a residency permit, freeing him to begin his life as a European citizen after nine years, nine months, one week, and three days spent languishing in a Dutch Asylum Center (ASC).

Although years in an immigration detention center anywhere can seem like a prison sentence*, The Leash and The Ball is a humorous and deeply moving novel that succeeds best at proving that even if you manage to get the man out of the ASC, achieving the reverse is near impossible. Whether one has read the prequel or not, one gets the feeling that Samir’s problems are far from over. In fact, the author’s choice to kick off his novel with “a glass door” as a first sentence is a clear indication of the fragility and precariousness of Samir’s present situation, whose “crucial to his life encounters” seem to “always happen at the wrong place and the wrong time.”

Armed with health insurance, a sheet of paper that determines he can officially stay in the Netherlands, and a garbage bag full of old photo albums he’d collected from thrift stores over the years, Samir narrates his life story after the ASC, as he flits between one accommodation and the next “like water needing to purify itself.” His story leaves readers under no illusion as to the tortuous absurdity of his situation. Samir learns to navigate the cultural differences between the Iraqis and the Dutch and what integration really comes up against in a country full of incomprehensible rules and habits, as well as cruel and absurd legislative processes enforced on immigrants who, in order to live in safety, are left with no recourse but to endure. Especially consternating to Samir, whose plan is to travel to Tarifa, in the south of Spain — where the author also happens to live these days — is not only that he has to maintain the required five year-residency in the Netherlands before he can be issued a passport for onward travel, but that he has to wait for the official IND card in lieu of the temporary residency paper printed on a sheet of paper that he was handed at the ASC. All of this serves to extend the trauma of waiting that dominated his life at the ASC, which he sardonically compares to “fish neither still swimming in the ocean nor lying in a pan” — a purgatorial limbo of sorts.

What makes The Leash and The Ball vastly different from its prequel is the amount of insight it offers into Samir’s life growing up in a Shia village in the south of Iraq. It seems that with a semblance of “a life” on the horizon, he is ready to revisit his cache of homeland memories from which the final winter of the Iran-Iraq war would mark the last time he would ever be part of a complete family.

“Our house in Iraq was an address for misfortune. A bus stop for shrapnel wounds. A station for tears and grief, where the train of one’s life sometimes stood motionless for years on end.”

He tells of a brother, the first to flee Iraq to avoid conscription into Saddam’s army after graduating from university, before Samir and his younger brother follow suit when their turn comes up. His father dies before any of them can see him again. He recounts how another brother is killed by mortar fire, leaving his sister to die of grief a few months later. Yet another brother marries his college sweetheart, a Sunni from northern Mosul — a marriage the writer compares to that “of a German boy and Jewish girl during WWII.” They too finally flee to Turkey. One of the saddest reminiscences is when Samir recalls the death of a young friend who drowns in the Euphrates following a bet to dive into the water, despite the fact that he couldn’t swim. In Samir’s adult eyes the boy is relegated to hero status for the simple fact that heroes only die once, as opposed to asylum seekers who are fated to die a thousands times in one lifetime.

Samir’s observations of the Dutch idiosyncracies and mannerisms shine a light on the western perception of immigration as well as on family, friendship, faith, and love. His integration into Dutch society begins in the shed of the Van der Weerdes family, which he shares with a friend from the ASC. There he meets Leda and her dog Darius, whose leash and ball become Samir’s secret miracle to disarming Dutch society and law enforcement.

“As soon as they think you have a dog,” explains Samir “you might be a Muslim, but you’re a good one, not hardcore or scary. Once they see that a dog can live with a Muslim, then they realize that they can, too.”

As Samir changes residences from a shed to a monastery, to a student-sharing accommodation, and finally an apartment building that houses undocumented people and asylum seekers, dubbed Elvis Presley, we are treated to his internal struggle to reconcile who he really is and the place he comes from with the person he is meant to become as a Dutch citizen. All the while we are conscious of the precarious balance between his pain at being ignored as an adult foreigner by the Dutch, and gratitude for the boring and tranquil Dutch streets (rivers of time), neighborhoods (lakes of silence), and a city (an ocean of hurry) that remain “free of mortars out of the sky, free of mujahideen and soldiers…a paradise of peace and quiet.” Samir goes so far as to eventually opt out of using his tongue “as the loudspeaker for the war in Iraq, so as not to mar the gentle tranquility” of his adopted village.

Just as in Two blankets, Three Sheets, the novel brims with a colorful array of characters from different backgrounds and walks of life. However, it is always Samir, a lighthearted, honest, far from judgemental protagonist, whom readers root for as they bear witness to his evolving character and sense of self, for he holds up his identity as an Iraqi from an Arab culture that is like “a cage that keeps closing in on your soul until there is no room to move,” against that of a Netherlander in possession of a culture in which one can go places and disappear into the woodwork if one so chooses.

To Samir’s consternation, both cultures come up lacking. At one point he writes, “I lost my faith in God during the war, my faith in the world after crossing the Iraqi border, and my faith in myself in the ASC.” That said, it is doubly heartbreaking when despite all of Samir’s best intentions to integrate, he discovers that it is in fact the system, not the Dutch people who are more intent on war movies and an eternal war with clutter than with anyone else, that proves to be his most ardent opponent, opposing and undermining him. He is forced to make arduous decisions that cost him his roots, his ground, his water, and his air. That, he concedes, “is the price someone pays for fleeing, for leaving his country behind, when it needs him to stay.”

Despite seeming repetitive and slow in some parts, The Leash and The Ball is a highly engaging novel that comes across as buoyant, not withstanding its themes of trauma, grief, a doomed relationship, and immigration ennui. Al Galidi is a writer who obviously refuses to succumb to victimhood, and instead opts to unsheathe human foibles through the conduit of humor, in which “the loudest laugh comes from the deepest hurt.” Samir’s first-person conversational, everyday narrative allows the novel an accessibility that is both enchanting and disarming — reinforcing Samir’s conviction that what brings people together is not religion nor ethnic background, but food, music and literature.

The Leash and The Ball, like its predecessor, was written by Al-Galidi in Dutch — a language he taught himself to read and write while in the ASC. Both novels are published by World Editions and translated by US-born, Amsterdam resident Jonathan Reeder.

The US publication of The Leash and The Ball is set for September 20.

* The case of Iranian asylum seeker to Australia, Behrouz Boochani, detailed in the New York Times, is an extreme example of a life wasting away in an isolated detention camp.