Outside of Athens, a family gathers — two cast-off sons, two repentant mothers — to exchange gifts, silences, and perhaps, forgiveness.

“Including those from this year, I’ve surpassed two hundred.”

“Each year we throw away money on camels and little sheep.”

“Let me be a child again. The holidays don’t last long.”

“Do you really like that plastic crap? Why don’t you buy stuffed animals, or crystal ones, porcelain, ceramic?”

“Since when have you had taste?”

“Our finances are my responsibility.”

“You mind is stuck on investments.”

“Fortunately, it’s still sharp.”

“I love tacky things. You love only the handsome?”

“Have a look in the mirror and you’ve got your reply.”

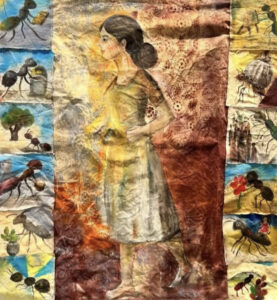

The small rotunda table is pushed up against the living room windows. The silk tablecloth is the color of the desert. The stubby synthetic tree, decorated with red balls, stands in the middle of the table. Beneath the low branches, at the tree’s base, is a papier-mâché nativity scene with papier-mâché figures of Joseph, the Holy Virgin, and Baby Jesus. They’ve had it for years. Around them sprout camels, goats, lambs, birds, deer, pigs, chickens, dogs, cats. Tolis struggles to squeeze it all in. The table doesn’t comfortably accommodate two hundred zoo pieces. It’s a tight fit.

Tolis is a grown man. Ηe’s not pretending to be a baby. Ηe simply allows himself this small ten-day joy. After all, there are strapping white-haired fellows who lie down on the floor, lay rails, and crawl around playing with trains. There are also compulsive collectors who, on a daily basis, spend money and time setting up a thousand lead soldiers according to the battle plans of Austerlitz.

It occurs to him that — especially this evening — he might be misunderstood, but he prefers to finally be himself. Yes, at this critical dinner party, despite his justified panic, he will be himself.

He looks around: the living room is tidied, the sofa covers clean, the throw pillows plentiful and fluffed, the table laden with bowls of very soft chocolates and very light cookies sprinkled with powdered sugar. He looks at the walls from which two framed photographs have been removed. Everything is appropriate for the occasion. In the place of honor, always steadfast on its own white wall, is the large icon from the Great Lavra Monastery.

Are the red geraniums in the three vases sufficient? Naturally they are sufficient. It’s not necessary to buy holiday poinsettias. Better flowers from their own garden only, which is well looked after, with its trademark geraniums, full of blooms all year long, at least eighty of them in the flower beds.

They’ve been in Kineta for thirty years, in a house high up, with a view of the sea, which is never empty of ships. In this corner of Attica, full of closed-up summer houses, illuminated ships tread the dark, rendering the winter nights and their isolation more amiable.

The idea of Kineta came from the actress Zozo Sapountzaki, whose villa made Kineta known all over Greece. Tolis and Miltos were looking for something slightly outside Athens, a place where they wouldn’t be too close to neighbors, where they could keep a low profile. The times had forced them to become wary, to defend themselves, to keep a distance from stalking, talebearing, and gossip.

They developed quirks, of course — that was the price. But they endured, found their own way.

Twenty minutes past eleven. Miltos, today even more hypochondriac regarding tidiness, recleans the bathroom, new cream soaps, air freshener, well-ironed towels. Tolis praises him: “Perfect.”

Miltos reminisces out loud: “We didn’t have an indoor toilet. The privy was outside. Turkish-style. I spent hours on it, swaying on my legs and daydreaming.”

“Poor thing.”

“Not really. It was wonderful. I’m telling you, I used to daydream.”

“Grand.”

“I wonder if Turkish toilets are better than modern ones.”

“When I used to beg you to go to Turkey, saying come on, my dear Tolis, that TV presenter Koromila says we should make a pilgrimage to the bloodied lands, you said that she wears people out with unending tours, mountain climbing, trekking, and coaches on cliffs. What are we supposed to do with a Turkish toilet now?”

“We’ll daydream.”

“You’re sixty, not six. If you fall on your ass, you won’t be able to get up again.”

“Leave. Right now. But don’t go far, only five meters.”

Five meters away is the kitchen, Miltos’s kingdom, along with the kingdom’s law-abiding citizens — his pots.

The morning’s shopping is on the counter, purchased from the same supermarket where they will shop until death, parking and unparking on autopilot. Through the bright window, a ship can be seen far off. Miltos stands there, watches it slowly sailing. He feels joyful. He loves passing ships as long as they are not navy ships, and he loves September showers, as long as he has already collected the laundry from the line. He loves birds unconditionally. When their canary died, he was hard hit.

“What do you think? This evening, will we be melancholy before or after? Let’s decide,” Tolis says.

“This evening we’ll do our best not to be melancholy. We’ll eat, drink, exchange holiday wishes, and tell tasteful jokes.”

“I’m thinking of making the Asian cabbage salad that I read about in the magazine on the plane.”

“I feel the same about cabbage salad as I feel about you. I don’t want to risk getting to know another side of you.”

The next few hours fly by in anticipation of the big evening: Friday, December 24, 2010. They are opening their house for a Christmas Eve party that fills their hearts with anxiety and emotion. So, they check every corner, shelf, hand towel, and rug. They recheck the ingredients for the menu and do everything they possibly can to reduce the likelihood of anything ruining the holiday mood.

Tolis, unwilling to leave the background music to chance, examines the CDs and selects those that are appropriate.

Miltos replaces the red geraniums with white geraniums in the small vase near the silver-framed photograph of his late father. He always arranges the vases better while praying silently.

Tolis freshens the slightly wrinkled bows on the two gift packages.

Miltos counts €100 banknotes and puts ten each into two envelopes. He seals them with saliva.

Like wind-up soldiers, they move about with precision and agility. Even though they finish their tasks one after the other, instead of feeling more relaxed, their anxiety increases.

Tolis nervously passes his hand through his short hair. “Is my haircut alright?”

“Like Sakis Rouvas.”

They sit for a little while, a small break during which each does a recap inside his own head. The present day imposes retrospection — it shows on their faces and in their eyes.

Now, in their late sixties, already retired.

Tolis was an accountant for forty years in a novelty department store. Cut off from his family, half the responsibility his, the other half theirs.

Miltos, an expat from Chicago, sent there from Greece at the age of ten. He got involved with his own pastry shop, which he sold before he turned thirty. He said goodbye to his frigid adopted parents and returned to Greece only to find the door of his family’s house closed to him.

The Athens districts of Kolonos and Aspropyrgos became forbidden zones. Kineta was a refuge where they wouldn’t be stoned by thugs, where they could live the life that they had chosen.

A private life, acquaintances kept at a distance. A few disappeared definitively when their sons became teenagers. The further away the others went, the more the two of them became attached to one other, day by day reconciling the differences in their characters. One was a spendthrift, a silly romantic, a whiner. The other was frugal, square, funny, and an expert in the prevention of detours into hysteria and tears.

For unavoidable crises, they found a convenient type of dialogue between arguing and joking, as well as a liberating type of silence between war and peace. With time, both battle-hardened, they pinned on each other’s lapels Medals of Honor for patience and Medals of Arts for self-sarcasm — that is, a gardenia or some shiny bitter orange blossom.

The view helped a lot. They’d sit on the veranda and look at it for hours.

The crime novels that they read together also helped, not because they loved murders and mysteries, but because they adored the detectives who were always eating club sandwiches.

Music also helped, lyrics and melodies, the reserve of the heart.

It’s midday already. Tolis announces the end of quiet time by playing a CD: Αthens, white marble columns, the lilies of the Acropolis. He brings bread and cheese for two.

“Miltos, can you imagine Greece without Nana Mouschouri?”

“Why, did Bulgaria take her?”

“You don’t love the great voices as much as I do. Are you jealous?”

“I include Vicky Moscholiou in my prayers.”

“So that God will keep her strong?”

“So that the earth covering her will be light. We had good times while listening to her songs.”

They listen, eat, gather the plates, tidy up.

Preparation of the meal and the dessert, Miltos’s job. Washing of the already washed car, Tolis’s job. He’s the driver, the one who’s going to go pick up the girls this evening.

Time passes, the light fades, the sponge cake smells delightfully, the stress increases.

Every mother is a Colossus of Rhodes in the thoughts of her child.

In his black Italian suit and well-polished shoes, the chauffeur is ready to leave. At the last second he balks, turns pale, sits in a chair, asks for a glass of water. “Is it terrible that I wasn’t daring and brave?” Tolis asks.

“You mean like Commander Karaiskakis?”

“Maybe I insulted life by letting it pass by while I sat tight in my nest?”

“Tolis, we’re two fags. We’re not James Bond.”

“Did we hurt anyone?”

“Not even a mosquito.”

“Did they hurt us?”

“Plenty of scorpions stung us.”

“Will this evening go well with the girls? We’re taking exams.”

“The Holy Virgin is on our side.”

“Sometimes I’m afraid of her.”

“She’s always showing mercy to this person and that person. Is she going to exclude us? Sometimes I feel her beside us.”

“How do you mean?”

“In the Opel. She reminds you to turn on the signal in time.”

After Tolis left, Miltos lit the votive lamp in his bedroom according to his daily ritual. He turned up the heating a bit and set the table for four. At the last second, sure that they would make a good impression, he decided to bring in two branches from their flowering almond tree. He liked those pink flowers. They would lend a tone of levity and innocence, breaking up the whiteness of the tablecloth and plates.

At eight he was standing at the door, formally dressed.

His eye on his watch, his ear on the sounds of the few passing cars.

At ten minutes past eight, the Opel appeared. Miltos crumpled, fell to his knees.

That was how he received the two women whom Tolis carefully helped out of the car and up the three steps.

First Miltos grasped with both hands his mother’s right hand and kissed her fingers one by one, five kisses.

Then he kissed Tolis’s mother’s hand.

He would have liked to remain an entire year kneeling reverently, caressing and kissing and forgiving those elderly hands.

He struggled to his feet. They passed inside. Each one affectionately seated his own mother in a predetermined armchair. The two black-clad, tearful, flustered old women — Tolis’s mama holding her heart, Miltos’s mama clutching at her headscarf — filled the living room with the scent of family.

How we long for our mothers, even when we pretend that we have forgotten them, regardless of whether they left our lives because of disagreements or death. Every mother is a Colossus of Rhodes in the thoughts of her child.

While their fathers were still alive — the fathers who had written them off as a shame to the family — Tolis and Miltos saw their mothers in secret. Afterward they saw them a bit more, always with embarrassment and always separately.

That evening, with a delay of decades, the two mothers met and, more importantly, each met the companion of her child. Introductions without words, a simple handshake, a lowered gaze.

The dinner was Tolis’s idea. The last few weeks he had been dreaming either of weddings, which symbolize sorrow, or of children, which symbolize suffering. In the morning you open a window, recount the dream, lower the blinds, close the window, and then everything’s okay — the advice of Miltos, an expert in such things.

But they unavoidably remembered the screeching an oaf-cousin who’d sent them sugared almonds as soon as they moved to Kineta. And they remembered a slutty accountant who had called them fairies when she didn’t receive an expensive wedding present. And they were saddened by the subject of children. Heartbroken, in fact.

With so much reminiscing, it occurred to them that one of their old ladies might die soon. Tolis’s mother was eighty-six, Miltos’s eighty-three. In the end, they agreed that next Christmas — a holy day — would be an opportunity to arrange a meeting. Perhaps there was still time for Peace on Earth.

How did things turn out?

In the beginning, around the manger. After periscopic glances at the immaculate living room, the mothers limped over to the rotunda and sat in the two chairs beside it. They crossed themselves and got involved with examining the plastic animals. Tolis’s mother reached out and lifted a fallen lamb. Miltos’s mother straightened the leaning Joseph.

The first hour passed.

Ten minutes of gifts followed. One mother gave them two men’s colognes, the other mother presented a small wooden icon of Saint Panteleimon, restorer of health and patron of the elderly. They opened their gifts, the warm jacket useful, the leather handbag useful, the €100 banknotes useful. The sons regularly sent little envelopes, whatever they could spare and more.

Miltos was worried about their bank account, which was emptying rapidly. Prime Minister Papandreou is to blame, he’d say, that man is capable of pocketing even the twenty-cent coins left in churches for votive candles. Miltos resigned himself definitively from his vow to do a holy places world tour as a duo: the Holy Sepulcher, Notre Dame of Paris, Lourdes, Compostela. We’ll content ourselves instead with Our Lady of Tinos and Our Lady of Soumela in Veria. They’re good too, more economical.

The meal now: tender meat, smooth mashed potatoes. Even though they had Plan A to watch the holiday program on television, Plan B to listen to light songs from the fifties, and Plan C to play a video with a Vougiouklaki movie, something better happened: silence.

Silently they swallowed a few bites and set down their forks. Silently they turned their heads toward the window, as if they expected the crews of the three passing ships to join them.

The sacred silence wiped out the words and ultimatums of their fathers: the neighborhood is ridiculing me because my son is a fruit, he’s no son of mine, he should get the hell out of here and return to Chicago, let the “Americans” take him — meaning Miltos’s childless, stingy, and severe uncle and aunt, may they rest in peace.

Serene silences occur every day among all good families. In any real home, people are free not to speak. Gathered together that evening in Kineta, then, were all the beautiful lost silences of so many years. They didn’t allow any awkward words to escape them. The silences said everything. They broke the ice of emotions.

All four became statues. They couldn’t get enough of this aching love, which managed to escape from closed mouths.

At about ten thirty, Tolis got up, took the car keys, and lightly touched his mother’s shoulder. According to Miltos’s express wishes, Tolis had hardly wet his lips with wine so that he could take the girls safely home.

“Wait just a moment,” said Miltos’s mother.

She took from her pocket a small package casually wrapped in tin foil and bound with a ribbon. She untied and undressed it: an aspirin box. But instead of pills, it contained her gold wedding ring, wrapped in cotton. Miltos recognized it from the tiny transparent blue stone, his mother’s only piece of jewelry, a cheap thing suited to the budget of his street vendor and always dirt-poor father.

“For you, Mister Tolis,” said the old lady, extending to him the ring in her open palm.

The scene did not include hugs, kisses, sobs, or applause.

With the ring on the pinky finger of his left hand — that’s where it finally fit — Tolis glowed. He felt golden from head to toe, ridiculous, and happy.

Miltos felt the same and more. Bravo to his completely illiterate mother, he thought. Astonished and ecstatic, he remembered how, when he was a child, still in his father’s house before they gave him up for adoption, the greatest achievement of his mother’s miserable life was to go every Sunday to church and hold open a borrowed New Testament that she did not know how to read.

There is a Greek wedding wish that goes like this: may you love each other as a jenny loves her foals. Because a jenny — a female donkey — is the best mother. If you take her foal, she breaks down crying. If her foal falls into a ditch, she follows it. His mother did not turn out to be a jenny, but just now she showed motherly courage. A heroic gesture.

He observed her face and calculated how much he resembled her. Old age reveals common characteristics. The same thin hooked nose, the same pointy chin, the same grey hair as hard as bristles, the same weighty gaze, which constantly holds before it the mistakes and slaps of an entire life.

He turned discreetly toward the other old lady. She did not avoid his gaze.

The evening ended with four thank-yous, one from each to the others, whispered, humble, and redemptive. At the last second, Tolis gave a handful of little deer to one mother, a handful of little pigs to the other. A well-received offering, which opened up space on the rotunda.

On the delivery route, the men up front, middle-aged with their extra kilos and bags under their eyes. The women in back, with all the heavy damage of age. Around them, Attica was resplendent, a paradise without enemies.

Tears could wait for later — whatever happened to come up, beginning with the vicious beating that Tolis received while a soldier and ending in Korea with Miltos’s service on the American destroyer, six months of seasickness and vomiting. To avoid such effusions and too much seriousness, they turned on the radio and did a circuit of the stations. There was lot of chatter, silly jokes, sappy ballads. They found Celine Dion, a heavenly voice, perfect for Christmas Eve.

The songs in a foreign language served their purpose well, taking them to Aspropyrgos, Kolonos, and back, without ever overshadowing that tiny phrase, for you, Mister Tolis — an entire Gospel in itself.

Excerpt from Καιρός σκεπτικός (Kastaniotis Editions, 2011).