Opinions published in The Markaz Review reflect the perspective of their authors

and do not necessarily represent TMR.

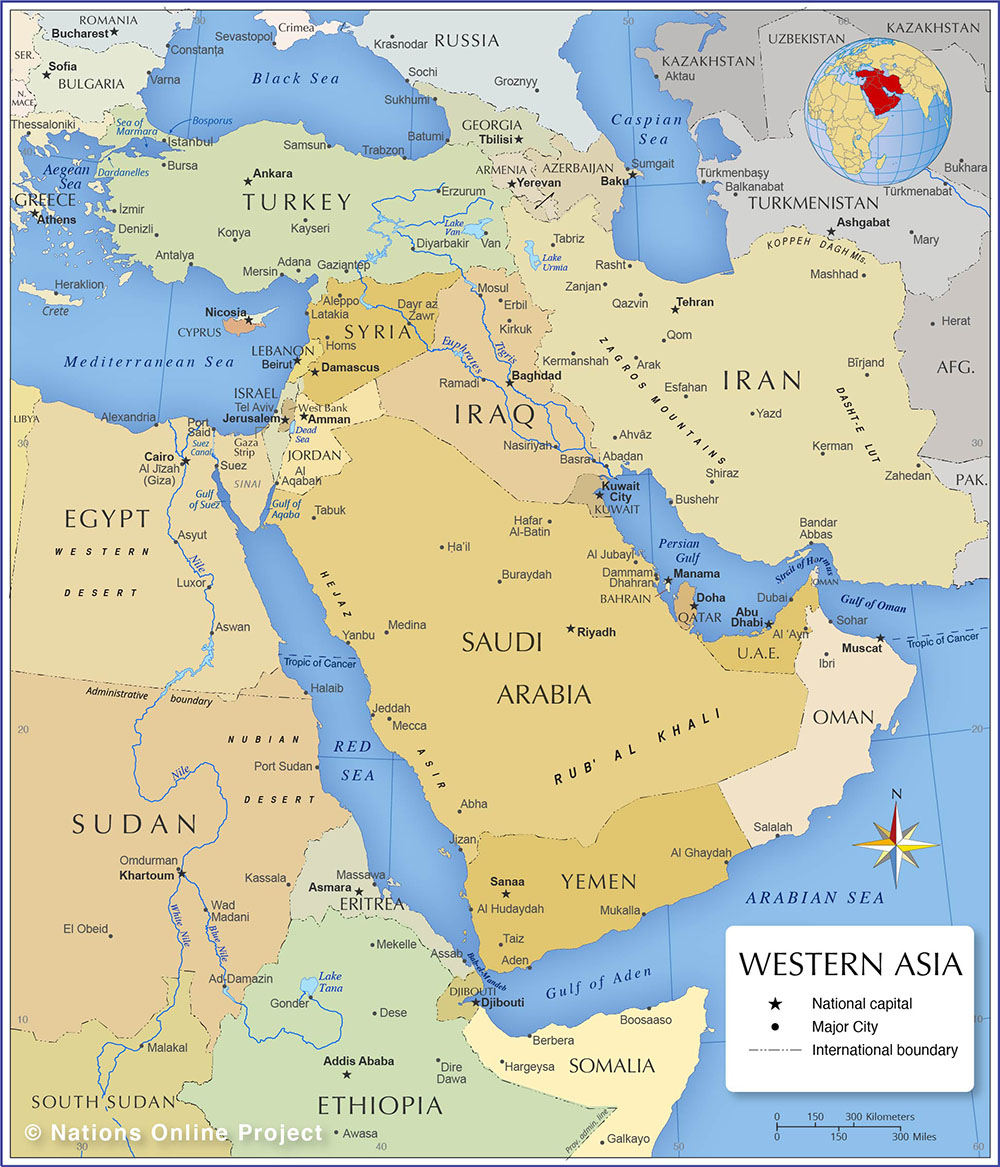

We’re no longer talking about “the greater Middle East,” but a swath of West Asia that increasingly operates outside the geopolitical influence of the United States.

Chas Freeman

Names make a difference. Those who confer them reveal their perspectives on the places and peoples they are naming.

Over the course of the 16th to the 19th centuries, Europeans conquered and colonized the world, imposing their self-centered perspectives on its geography. For them, the Ottoman Empire was “the Near East,” a region encompassing West Asia, Southeast Europe, and Northeast Africa. Then, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the United States became the preeminent component of the self-styled “West,” a trans-Atlantic perspective supplanted the European one.

From the point of view of Americans, the lands within the collapsing Ottoman Empire were an intermediate zone between Europe — the Eurasian subcontinent to the East of the United States — and the Indian subcontinent. [1] That’s why Alfred Thayer Mahan decided they should be called the “Middle East,” not the “Near East.” In time, even the people who lived there began to use this American-minted term. The largest newspaper in the Arab world is الشرق الأوسط – which means “the Middle East.”

The Birth of the Nation-State in West Asia

The name persists, but the people living in the region no longer acquiesce in foreign definitions of their homelands’ place in world affairs. Ottoman cosmopolitanism disappeared when the Ottoman Empire and the Caliphate expired. After flirting with a variety of transnational ideological identities — including pan-Arabism, Ba`athism, Judaism, Sunni, and Shi`ite Islamism — the region’s peoples have redefined themselves as “nation states.” Türkiye [2] and the fragments of the Ottoman Sultanate’s Levantine territories carved into semi-independent, neo-colonially administered countries by British and French bureaucrats have acquired well-defined international personalities.

Iran, Iraq, Israel, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria have come to embrace strong national identities that have survived multiple external and internal challenges to their existence.

Iran has broken with its neocolonialist patrons, installed a defiantly independent Shi`ite government, and asserted its own sphere of influence in West Asia. In this century alone, Iraq has experienced a period of governance as a “thugdom,” an anarchy imposed by a botched American effort at hit-and-run democratization, and the slaughter by foreign and domestic forces of at least half a million of its population.

Israel has degenerated from the vaguely humanistic vision of early Jewish nationalism to today’s Zionist negation of universal Jewish values. The indigenous people of Palestine have been the continuous object of relentless genocidal dispossession and brutal oppression by the Zionist settler state. Lebanon, once the playground of French confessional politics and Arab hedonism, has become ungovernable. Syria has been isolated, vivisected, and devastated by coalitions of domestic forces supported by external actors, including the Gulf Arabs, Israel, Türkiye, and the United States.

Syria continues to be the locus of a variety of proxy wars, including between Israel and Iran, Russia and the United States, and Türkiye and Kurdish separatists.

Meanwhile, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, once proudly pan-Islamist rather than pan-Arabist or nationalist, has embraced nationalism. It celebrates its official founding as a state in 1932 and employs the international — not the Hijra — calendar to do so. Egypt retains its distinctive character and cultural identity under a comprehensive military dictatorship. Oman, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) practice independent foreign policies and exercise influence not just regionally but globally. Kuwait — which is surrounded by Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia — is appropriately cautious. Bahrain defers to Saudi Arabia and serves it as a useful proxy in contacts with Israel and the United States military.

Geopolitical Centrality

What has not changed is West Asia’s geopolitical centrality. It is where Africa, Asia, and Europe and the routes that connect them meet. The region’s cultures cast a deep shadow across northern Africa, Central, South and Southeast Asia, and the Mediterranean. It is the epicenter of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the three “Abrahamic religions” that together shape the faiths and moral standards of over three-fifths of humankind. This gives the region global reach. But as the countries of West Asia seek their own destinies, they have graduated from subordination to great power rivalries and ended their vulnerability to external efforts to impose alien ideologies like Marxism or representative government. Political Islam, their original answer to these foreign systems of government, is in retreat. The peoples of the region are reinventing themselves in accordance with their own traditions of monarchy, military dictatorship, consultative politics, parliamentary democracy, or theocracy.

As the rule of law everywhere yields to populism (including in our own country), Aristotle’s observation that democracy tends to degenerate into demagoguery, autocracy, and the tyranny of the majority seems to be being born out. Various forms of elected autocracy are flourishing in Russia and Turkey and taking root in India and Israel.

Colonial Dominance

The era of foreign dominance of the crossroads of the world that began with Napoleon’s 1798 invasion and occupation of Egypt is clearly over. This should not surprise us. It has been two-thirds of a century since Egypt forced the British and French to cede control of the Suez Canal. Britain abandoned imperial ambitions east of Suez 56 years ago. Forty-four years have passed since Iranians expelled their Shah, who had been installed in an infamous Anglo-American regime-change operation a quarter century earlier. The Cold War, which long dominated regional politics, ended 34 years ago. “9/11,” which fundamentally estranged the region from the United States, occurred more than two decades — a full generation — ago. The Arab uprisings of 2011 are a distant, garbled memory for all but their participants. The world has undergone fundamental change, and so has Afro-Asia — West Asia and Northeast Africa.

Among the changes is the reduced appeal of alien intellectual traditions and systems of government. Marxism is pretty much dead as an ideology except at the Central Party School in Beijing and a few institutions of higher learning in the Anglosphere. As the rule of law everywhere yields to populism (including in our own country), Aristotle’s observation that democracy tends to degenerate into demagoguery, autocracy, and the tyranny of the majority seems to be being born out. Various forms of elected autocracy are flourishing in Russia and Turkey and taking root in India and Israel. In this context, Washington’s efforts to portray world events as driven by a grand contest between democracy and authoritarianism have little appeal abroad, where they strike many as both irrelevant and seriously detached from reality.

Breakout to Multiple, Simultaneous Alignments

But this is only part of the reason that, by contrast with the Cold War, the countries of West Asia (with the notable exception of Iran) have opted for nonalignment between the United States and America’s designated Chinese and Russian adversaries. To have called West Asian client states and dependencies like Israel and the Gulf Arabs “allies” of any great power was to seriously misunderstand and misdescribe their status. They were and, to some extent, remain “protected states,” consumers of security supplied by foreign backers rather than providers or guarantors of security to these backers. States in the region have been more likely to embroil their patrons in wars than to save them from enmeshment in them. Now, rather than attaching themselves to a single protector, these states have filled their dance cards with multiple great power partners. They offer fealty to none.

Iran, too, was originally nonaligned between East and West. But decades of U.S. policies of ostracism and “maximum pressure” left it nowhere else to go but into the arms of America’s adversaries. Iran has now turned to them to help it evict American influence from the region. In support of Moscow’s proxy war with the United States in Ukraine, Tehran has become a supplier of drones, artillery shells, tank ammunition, and other weapons systems to Russia. And it is working with India and Russia to develop an International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) that will bypass the NATO-controlled sea route through the Bosphorus as well as the Suez Canal. The INSTC will link Russia with the Iranian port of Chabahar, connecting Moscow to Bombay and other ports on the Indian west coast.

Unlike the United States, China has worked hard to maintain untroubled relations with all the nations of the region. This has been of particular benefit to Iran, recently helping it to restore normal relations with previously hostile Arab neighbors. Among other benefits, this rapprochement breaks the American-imposed embargo by opening Iran to trade and investment from the capital-rich societies across the Persian Gulf. Meanwhile, new roads, railways, and energy pipelines financed by China’s Belt and Road Initiative promise to restore Iran to its premodern role as a regional hub for both east-west and north-south economic exchanges.

As Iran did four decades ago, the Arab states of the region are now also in the process of freeing themselves from past patron-client relationships. Their interactions with Britain, France, the Soviet Union, or the United States were inherently unequal. In return for protection, these countries offered obsequious deference to their patrons’ interests and policies but undertook no reciprocal obligations. They made no commitments to aid in the defense of their patrons’ regional interests, which included security of energy supplies, assured overflight and transit, market access, counterterrorism, and the exemption of Israel from global pressure to conform to the norms of international law.

Israel now faces some of the same dilemmas in its relationships with the United States and other external powers that its Arab neighbors have long confronted. It chafes under its continuing overdependence on support from the United States and sees aligning with America against China and Russia as contrary to its own interests. Israel can no longer claim shared values with American idealists, though it retains the enthusiastic support of diehard Zionists as well as U.S. racists and religious bigots. Like others in its region, Israel is under pressure from the United States to change both its foreign and domestic policies, though fear of political reprisals or the loss of electoral support from the American Israel lobby continues to suppress public criticism of it by U.S. politicians.

The Ebb of U.S. Influence and the Regional Pursuit of Strategic Autonomy

In the final decade of the 20th century — a period that the late Charles Krauthammer evocatively named “the unipolar moment” in global affairs — the United States eclipsed all other external powers as the protector and patron of both the Arab states of the region and Israel. In 1973, in response to Egypt’s surprise attack on Israeli forces occupying the Sinai, the United States provided massive military support that enabled a successful Israeli counteroffensive. In the immediate aftermath of the Cold War, Washington came to the aid of the Gulf Arabs against Iraqi aggression but then began to levy ideological and other demands that they found inappropriate and unacceptable. After “9/11,” Americans embraced Islamophobia. As the second decade of the 21st century began, the United States not only failed to support erstwhile protégés like Hosni Mubarak against overthrow but — in the name of “democracy” — appeared to applaud their removal from power. These events deprived previous U.S. pledges of protection of client states and their leaders in West Asia of almost all credibility. The rest of it disappeared when Washington failed to respond to various moves by Iran against Gulf Arab interests and freedom of navigation in the Strait of Hormuz.

Now, as the Gulf Arabs separate themselves from past deference to and exclusive dependence on the United States, they do not seek and will not accept subordination to China, India, Russia, or others outside their region. The protection of these other external actors is, in any event, not on offer.

What is happening is not, as Washington mindlessly asserts, an effort by China, Russia, or any other great power to replace American hegemony in the so-called “Middle East” with its own. Nor are the states of the region either open to or in search of alternative dependent relationships. They are in active pursuit of strategic autonomy through diversification away from political and economic overdependence on the United States.

Such autonomy will not come easily. In practice, there are limits to the extent to which the states of West Asia can hope to wean themselves from military reliance on America. No other great power has either the disposition or the capability to accept the burdens of defending them against each other or external enemies as the United States once did. West Asian states are happy to exploit “great power rivalry,” but they are not driven by it. If they cannot extract defense commitments from great external powers, they must take responsibility for their own defense. They are beginning to do so.

The Special Difficulties of Israel

Israel faces an especially challenging transition. Zionism’s Ashkenazi founders agreed with their European Christian persecutors that Jews were an ethnic group rather than a religious community. As such, Zionism asserted, Jews were as entitled to self-determination as other ethnic minorities in Europe’s collapsing empires. Zionists sought Jewish independence in the mythic Jewish homeland, Palestine, which — with the racist condescension toward non-European native peoples that was typical of the time — they described as “a land without a people,” dismissing the resident Palestinian population as unworthy of acknowledgment, let alone recognition. This sowed the seeds of today’s Zionist state, which practices segregation against Arab Israelis in Israel proper, denies basic rights to West Bank Palestinians, seeks to drive them into exile by evicting them from their homes, destroying their farms, and conducting pogroms against them, and deliberately immiserates and occasionally massacres the nearly 2.2 million Palestinians it has imprisoned in Gaza.

This behavior, not surprisingly, incites both wider Arab hatred of Israel and global abhorrence of Zionism. It jeopardizes the US-sponsored “Abraham Accords” by making them seem a cynical project of autocratic Arab ruling families imposed over the opposition of most of their subjects, who continue to see Israel as an inherently illegitimate, foreign-supported, anti-Arab settler state. Since Iran turned against it, Israel has been unable to develop any friends in its own region, despite strenuous American efforts to help it do so. Its denials of ready access to Muslims seeking to worship at the al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem (Islam’s third holy city), not to mention Jewish extremists’ escalating assaults on the site, offend the global Muslim community. Only in India, where Hindutva is on the rise, have Israeli extremists found a religious nationalism to match their own antipathies to Christianity and Islam.

The extremist parties that now control the Israeli government provide daily evidence of their racist hatred for Palestinians, disdain for American and European Jews, denigration of liberal Israelis, contempt for goyim, and full-blooded support for and incitement of settler thuggery and violence. They have just overridden the independence of their country’s judiciary. They propose to give its government the power to lock up Jewish Israeli citizens in pre-trial detention in much the same way that it has long imprisoned stateless Palestinians.

These extremists are creating a deep rift between Jewish Israelis, destabilizing Israel’s economy, catalyzing a loss of confidence in Israel’s future, and causing foreign investors to flee. The streets remain filled with protesters and much of the Israeli air force is on strike. Abraham Lincoln’s prescient observation (in 1858) that “a house divided cannot stand” seems very relevant to Israel’s future. Israeli threats to attack Iran now sound less like plans than like bravado — efforts to use a foreign threat to paper over domestic divisions and conceal Israeli weakness, while warning others in the region that Israel remains its premier military power.

Zionist excesses are not just dividing Israelis — many of whom are emigrating — but seriously disillusioning and estranging previously sympathetic and supportive Jews in Europe and the Americas. Their backing and that of fundamentalist Christians has been as essential to sustaining Israel as that of European Catholics was to the survival of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 11th and 13th centuries. Israel will find it more difficult than its Arab neighbors to diversify the sources of its international support. No great power other than the United States seems prepared to overlook, let alone subsidize Israel’s brutal oppression of its captive Arab populations. And as the international role and stature of its Arab neighbors grow, the willingness of external great powers to offend them can only decline.

Meanwhile, Israel’s efforts to avoid taking sides in the Ukraine war despite its dependence on the United States and its large Russian-speaking population have not endeared it to either Washington or Moscow. Some of the Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs opposed to Russian President Vladimir Putin now reside in or claim citizenship in Israel. The United States has adamantly opposed Israeli outreach to China. If Israel loses the affections and politico-military protection of Americans, whose support for the Zionist cause now reflects both partisan and generational divisions, it will not find it easy to reposition itself geopolitically. Despite the Netanyahu government’s current efforts to cultivate China, India, and Russia, Israel has no feasible alternatives to dependence on the United States.

A Newly Assertive Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has faced a comparable challenge and responded with its own geopolitical repositioning. Saudi-American estrangement steadily deepened over the twenty-two years since the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York and Washington. These attacks led to the successful vilification of Saudi Arabia, other Arab nations, and Islam in American politics. The inability of Americans to distinguish between the Saudi establishment and its al Qaeda enemies was a shock to ordinary, previously pro-American Saudis as well as to the ruling Al Sa`ud. Washington’s subsequent failure to oppose the mobs that toppled Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak — its longstanding protégé — from power in 2011 then cost it the confidence of the Al Sa`ud and other Arab rulers previously reliant on backing by the United States. Their concerns deepened when the U.S. failed to respond to Iranian-backed attacks on Saudi and Emirati petroleum facilities as well as shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, and military bases in Abu Dhabi. The Saudis and other Gulf Arabs saw this as creating an urgent imperative to develop alternatives to reliance on America. They redoubled their efforts to do so.

The gruesome murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 cemented the American shift from quiet support for Saudi Arabia to vocal antipathy toward it, overriding President Trump’s narcissistic minuet with it and leading to presidential candidate Joe Biden’s pledge to make both the Kingdom and Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al-Saud international pariahs. President Biden’s subsequent discovery, once in office, that U.S. interests require a cordial and cooperative relationship with the Kingdom led him to a belated effort to court both it and Crown Prince Mohammad. This has not succeeded. Vocally expressed opprobrium, even if formally retracted, does not encourage fealty. U.S. policies based on denunciatory diplomacy, unconditional support for Israel, and total animosity to Iran have clearly exceeded their sell-by date in the Arab Gulf states.

Far from being seen as a pariah, Saudi Arabia is now widely courted as a key player in global and regional geopolitics and finance, with the capacity to offer or withhold crucial cooperation or acquiescence on multiple issues of global concern.

Instead of renewing its previous deference to the United States, Saudi Arabia has built a strong consultative relationship with Russia, which, for all intents and purposes, it has now integrated into OPEC. It has courted China, its largest and most promising export market and biggest source of imports. The Kingdom is normalizing its relations with Iran, dealing a hard blow to the US-Israeli plan to rope the Gulf Arab states and Israel into an anti-Iranian coalition. It has made it clear that, while it is prepared to deal transactionally with Israel, normalization of ties with the Zionist state would cost both the United States and Israel far more than either could ever bring themselves to offer. Like Israel and the rest of West Asia (other than Iran), Saudi Arabia has declined to align itself with either the West or Russia in the Ukraine war. And — over American objections — the Kingdom is now normalizing diplomatic relations with Syria.

Outreach by Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al-Saud

Crown Prince Mohammad — who turned to China, India, and Russia when he was persona non grata in the West — has since exchanged visits with President Macron of France and President Erdoğan of Türkiye. He has received President Biden and the former British prime minister and their key subordinates in his homeland. He has just been invited to visit London. He has doubled down on efforts to craft relations and choose friendships with other countries that, in his judgment, best serve Saudi interests. As a result, along with the UAE and Qatar, which have adopted similar Realpolitik-based foreign policies that bypass or challenge American primacy, the Kingdom has emerged as a middle-ranking power with significant global reach. At the same time, Riyadh has sought to enhance its regional influence through rapprochement with the Syrian government it spent the previous twelve years trying to overthrow. And it has reopened its long-severed dialogue with Hamas. Far from being seen as a pariah, Saudi Arabia is now widely courted as a key player in global and regional geopolitics and finance, with the capacity to offer or withhold crucial cooperation or acquiescence on multiple issues of global concern. Consider, for example, the August 5-6 peace conference in Jeddah, which the Saudis reportedly convened in response to a U.S. request for their help in expanding support for Ukraine in the Global South.

Saudi custody of two of Islam’s three holy cities reinforces human ties to the roughly two billion members of the global Muslim community, for whom it is a religious duty to perform the Hajj or `Umrah pilgrimages. Under Crown Prince Mohammad, the Kingdom has tempered its idiosyncratically narrow-minded version of Islam and moved closer to its religion’s tolerant traditions. This, and the Kingdom’s leadership of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation and the Islamic Military Counter-Terrorism Coalition has reduced previous frictions with other, more permissive Muslim societies. The reduction of religious constraints on individual and group behavior in the Kingdom has begun to enable the flowering of its women’s talents. This has also facilitated foreign willingness to invest in Saudi Arabia’s expanding non-oil economy and the mega-projects it has launched as part of “Vision 2030.”

Toward a Gulf Arab Arms Industry

Saudi Arabia is far from alone in seeking to expand and diversify its international politico-economic relationships. Most commentaries focus on the efforts of the UAE and Qatar to consolidate ties with China and Russia. Like Israel, Dubai is now a major refuge for Russians seeking to avoid the complications to life in their country created by Western sanctions. The United States cited the UAE’s cordial military relationship with China as an excuse for aborting the transfer of F-35s the UAE had been promised to incentivize its normalization with Israel. But the success of Dubai as an international entrepôt, business, and financial center is stimulating increasing Saudi competition with the UAE in finance, trade, investment, surveillance technology, and armaments production. Saudi Arabia expects that its main investment vehicle, the Public Investment Fund, will have more than $2 trillion by 2030, making it the world’s largest. It has applied for membership in the so-called ‘BRICS’ and its New Development Bank.

The Saudis in particular, after decades of near total dependence on international arms imports, now seek to attract investment in their domestic military industries. This is a potential deathblow to the traditional American approach of insisting that the Kingdom and other protected states like the UAE not buy U.S. competitors’ weapons, while Washington simultaneously refuses to sell them U.S. alternatives. American policies that equate security with militarism, ignore political, economic, trade, and cultural factors, and rely on sanctions and ostracism rather than diplomatic dialogue have proven seriously counterproductive. This explains the paradox that, while U.S. air, naval, and ground forces continue to be present or to exercise in all six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council as well as in Iraq and Syria, the United States is perceived to be in retreat from the region.

The Fruits of West Asian Realpolitik

As great power dominance of West Asia recedes, the countries of the region are pursuing their own interests there through Realpolitik. This is enabling them to make progress on issues that had long been viewed as intractable. Five months ago, years of efforts by Iraq and Oman to facilitate the restoration of Saudi-Iranian relations culminated in the successful Chinese mediation of rapprochement between the two countries. Since then, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have normalized their previously hostile relations with Syria. Egypt and Turkey have moved to end the rift between them. The so-called “Abraham accords’ by which Bahrain and the UAE established diplomatic relations with Israel are yet another example of self-interested pragmatism producing progress. These accords reflected Arab states’ interest in harnessing the political power of the Israel Lobby in the United States to their advantage as well as in expanded access to U.S. weaponry. The Israel Lobby has since played its desired role, but the United States has failed to deliver the F-35s and other weapons systems it had pledged to provide.

The major exception to forward movement in the region is now the Israel-Palestine issue. Rising violence between Israel and its captive Arab populations has halted the development of Israel’s overt ties to Arab states and is estranging Israel from the West. Regional acceptance of Israel, desirable as it is, depends on Israel’s acceptance of the rights of its Arab subjects. But there is no current evidence of either American or Israeli willingness to grapple with this issue. There has been no ‘peace process’ for decades now and it has become apparent that what Israel means by “peace” is Palestinian surrender to Jewish supremacy and dispossession.

The Impact on the United States’ Regional and Global Roles

Sadly, on none of these issues is the United States now able to exercise effective leadership. Washington has no ties to Teheran or Damascus. It has strained relations with Riyadh, tense relations with Ankara, stagnant relations with Cairo, and mutually exasperated and deteriorating relations with Jerusalem. The region’s move away from the United States is reflected in the efforts of countries there to join the so-called BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organization and to use currencies other than the dollar for trade settlement. While they do not wish to sacrifice their relationships with the U.S., regional powers including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Egypt have signaled that they intend to take full advantage of these new openings as they prepare for a post-American, multipolar world.

De-dollarization is part of this evolution. It remains a work in progress but has been accelerated by apprehensions generated by the U.S. and European confiscation of Iran’s, Venezuela’s, and Russia’s dollar and gold reserves. These seizures made a mockery of the fiduciary responsibilities of central banks. They underscored the reality that the United States and its Western allies now make and break the rules of the post-World War II international order as they see fit. They raise serious doubts about the extent to which dollar deposits will remain reliable stores of value.

Still, despite the increased risk attached to holding dollars, for now the petrodollar agreement of 1973 remains in force. This agreement enabled the dollar — having just become a fiat currency no longer backed by gold — to continue as the universal medium of transactions in commodity markets, like energy and raw materials. Under it, the Saudis — and by extension, other members of OPEC — agreed to maintain their currency reserves in dollars and to reinvest any dollars they received for their oil in the United States. The resulting ability of the United States to print money rather than export goods and services that balance its imports is both unique and the basis of American global primacy. But the indefinite perpetuation of the “exorbitant privilege” conferred on America by such monetary hegemony can no longer be taken for granted.

What Must Be Done?

There is a lot at stake for the United States with the newly cantankerous states of West Asia. The region remains a central feature of global geopolitics, but it is no longer a U.S. sphere of influence. Washington must adjust to the new reality that its erstwhile client states now see it as in their interest to maintain political, economic, and military relationships with multiple external partners. They will no longer afford America a monopoly of arms purchases and military presence. Nor will they defer to interests of the United States they cannot be persuaded to see as their own. Such persuasion would require a level of respectful American diplomatic engagement with them not seen in decades. The countries of the region need reassurance that Washington is a reliable supporter of their interests rather than the unilateralist champion only of its own. To this end, the United States must earn their cooperation by offering tangible economic and political benefits. America will not succeed by focusing on preventing them from accepting such benefits from China or other great power competitors while offering no attractive alternatives.

The United States long recognized that both domestic and global prosperity require access to the hydrocarbon resources of the Persian Gulf region and acted unilaterally to protect such access. Despite the U.S. reemergence as a net energy exporter and international competitor with West Asian oil and gas, the Persian Gulf retains its importance to the world economy. But the willingness and ability of Americans to shoulder the entire burden of protecting other nations’ access to Gulf hydrocarbons are not what they once were. Recent experience has made it next to impossible to convince anyone there that, in fact, the United States remains committed and ready to do what it once did in this regard. No country in West Asia is now prepared to rely exclusively on the U.S. to protect either its energy trade or its national identity.

There is growing interest in the region and beyond it in alternatives to fading American guarantees of global access to the energy the world needs to prosper. Such alternatives must be grounded in strengthened individual and collective defense capabilities by the region’s energy producers as well as by agreement between them not to obstruct each other’s exports. The major countries to which they export would also need to be involved. Much as the United States might prefer to restrict diplomatic and naval cooperation to “allies,” this would not be enough. China is now the largest importer of oil and gas from the Persian Gulf, followed by India. Both must be part of any multinational security arrangement and field an effective force structure to support it.

The prerequisite for effective burden-sharing is an agreement between the great external powers to set aside their military rivalry in the Persian Gulf in favor of protecting a common interest in sustaining global prosperity as well as their own wellbeing. The operative question is whether the United States, with our current “you’re with us or against us” mentality and obsession with “great power rivalry,” could muster the flexibility to help put in place a framework that would serve more than our own selfish interests. It is hard to be optimistic about this.

American subsidies for Israel and insistence on its unique exemption from the norms of international law, more than anything else, cause the world to dismiss U.S. claims to support justice, human rights, and democracy with skepticism bordering on derision.

It is even harder to be optimistic about the future of Israel, which continues a march to perdition that answers those who call it out and try to halt it with baseless smears of antisemitism. Israel was born in hope. It risks ending in tragedy, a victim of hubris and deaf inattention to the lamentations and warnings of its well-wishers. Israel’s demise, if it comes, will not be imposed by the Palestinian resistance to its injustices or by the hostility of its Arab neighbors. It will be by its own hands, with more than a little help from its American friends.

Sadly, the United States has been as much the enabler of Israel’s descent into self-destructive and obnoxious practices as is any person who gives money to an alcoholic to buy liquor. Unquestioning support for Israel remains essential to extracting campaign contributions from American armchair Zionists, but it creates nothing but moral hazard for Israel and makes it an albatross around the neck of U.S. foreign relations. American subsidies for Israel and insistence on its unique exemption from the norms of international law, more than anything else, cause the world to dismiss U.S. claims to support justice, human rights, and democracy with skepticism bordering on derision. Unless and until U.S. enablement ends, Israel will persist in behavior that dishonors Judaism, makes enemies for both itself and the United States, and jeopardizes not just its moral standing but its viability as a nation state.

The Dynamism of West Asia

For better or ill, West Asia has acquired a dynamism that demands the reconsideration and adjustment of longstanding American policies. The relationships between its countries and between them and the outside world are in flux. A rigid adherence to historical partnerships does not serve American interests. The United States must refrain from offering any country there an apparent blank check, rebuild ties where they have become strained, place American interests first, and be prepared to offer tough love to friends who violate those interests. This will require a competence at statecraft and skill at diplomacy that are not currently in evidence in U.S. foreign policy.

What worked in the unipolar moment or the Cold War that preceded it will not work either in the emerging multipolar world and or in the new multi-aligned West Asian regional order. To serve American interests in the new circumstances, U.S. policies require fundamental rethinking and redesign. Sadly, so far, there is little evidence that Americans are ready to rise to that challenge. But policies that fail to anticipate and accommodate change risk strategic surprise and humiliation by it.

[1] Europe’s “Far East” is across the Pacific from the United States: our Far West. We now call it East Asia, the Western Pacific, or “the Indo-Pacific.”

[2] At the Turkish government’s request, this is now the approved international rendering of the country’s name.

This text is edited from a talk given via video in remarks to the Middle East Forum of Falmouth by Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr. (USFS, Ret.), Visiting Scholar, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, on August 6, 2023.