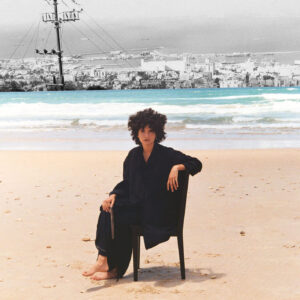

Alia Mossallam

In 2017, when we were still freshly arrived in Berlin, Asef Bayat, a friend and scholar we looked up to greatly, asked me and my husband what our plans were for the coming years. We laughed and said we had none. I had recently received a two-year fellowship to write my first book, and we were quite confident we would not stay more than a year in Germany. Before coming, I had even tried to negotiate a shorter contract. All we needed was “a year off” until things calmed down in Egypt.

We explained this to Asef laughingly, and he warned us we were falling into a trap. It was precisely what we should be wary of—he and many Iranians experienced it after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. There was a sense then that everything was temporary, that it would all change for the better, that all there was to do was wait. But some people have remained in this state of temporariness for decades since then. Living abroad without fully settling in, without buying furniture, waiting for conditions to clear up to allow for their return. What he described sounded like a spell. And his concern made it feel like we might be either cursed or entranced—depending on whether it came down to blindness or simply denial. “Don’t surrender to it… it is a permanent temporariness!” he said as we climbed into a bus, the doors slamming shut dramatically.

Standing Still

One of my most significant memories of the beginning of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution is of the new slogans. There are ones that I distinctly remember hearing for the first time, and ones that seemed to arise collectively in the moment. One of these was Ithbat: “stand still.”

I remember the evening of January 25 in Tahrir Square, when we decided to spend the night after having managed to occupy the square in large numbers for the first time in many years. We had been there since 3 p.m. By midnight the excitement had died down and plans were being made to sustain a sit-in for at least a few days. At this point, most journalists and human rights reporters had left the square. Suddenly, the lights went out. Then the shooting of rubber bullets and gas canisters began. And then, the stampede. My husband, friends, and I started running away from the source of the shooting, not sure where we were going. We ran at a measured pace, our arms locked together to ensure we didn’t lose each other.

Then came a faint and faraway shout from amidst the chaos: “Ithbat, ithbat!” The shout was picked up and could soon be heard in multiple voices, rippling across the crowd and gaining momentum until the scattered voices attempted to shout in unison, and until I could force myself to stop running and shout it too. I covered my ears and sobbed in fear while shouting over and over, my mouth opening to shout the word in the midst of a thunderous, thousand-voice-strong chant: “ITHBAT. ITHBAT. ITHBAT.” It continued until everyone stopped and remained still. Until the crowd felt strong enough in its unified roar, to attack rather than run from the police.

Ithbat comes from the Arabic root word thabat. It also means steadfastness, as in the context of al thabaat ‘ala al-mabda—staying true to one’s principles. Anything that is thabit is solid, unshakable. Hearing that word as a slogan evoked all these connotations. As I heard it, and repeated it, I tried to force every muscle in my body to be still, no matter how fearful I felt, no matter how strong the instinct was to run. I covered my ears and let my own voice and the voices of all the others echo within me.

Coming to Berlin often feels like the exact opposite of this moment. Like I couldn’t resist the urge to flee. That I packed up and left with my family for safety. Or maybe for a chance at happiness without being chased by the constant guilt of a “tomorrow that never came,” as one piece of graffiti in Cairo put it. I constantly feel like I left a diminishing number of people to fend for themselves—to have to stand and protect themselves, to fight to keep that space that we managed to liberate. As we leave, one after the other, those that remain are smaller in number and easier to target.

Prayer of Fear

In 2013, after the massacre of the sit-in in Rab’a al-Adawiyya Square [1], the poet Mahmoud Ezzat wrote a piece titled “The Prayer of Fear” (“Salat al khuf“). The title refers to a Muslim prayer that was made during times of war to eradicate or allay fear. The poem was translated by the Mosireen collective into several languages and shared on YouTube, narrated against a backdrop of footage of the bloodiest military atrocities in Egypt since 2011.

The poem repeats the greatest and most desperate wish: that one will emerge from “the trial,” from the battle, without losing oneself.

Are we winning?

Or are we in line for the slaughter?

Is the question shameful?

Or is the silence worse?

Did we open the way?

Or has it been destroyed?

Can injustice ever lead to gardens?

Can oppression be a gate to justice?

“Fi ‘adl babuh al dhulm?” Can oppression be a gate to justice?

“Fi ‘adl babuh al dhulm?” What justice can be reached through the doors of oppression?

The question of doors and paths was both pressing and recurring. Spray-painted on a wall near my home was the line, “The gate to a safe exit is welded shut.” The “safe exit” referred to the option that leaders of Arab countries had in 2011 to exit the scene safely — that is, to flee without a trial if they were to surrender and step down. At the time the graffiti meant that to leave untried would not be an option. As the years rolled on, the question turned on its head and we became the trapped ones. Is it because we trapped those leaders and their institutions in with us, not realizing how long their fangs or how deep their roots were? The gate to escape was locked for many of us, not only in terms of physical escape, but, more importantly, in finding a way to live daily life without being stuck in battle, weighed down by a sense of defeat, constantly hounded by the guilt of not having an opinion strong enough, not resisting hard enough against the horrors that were to come.

Deliver us from vision clear with the clarity of mountains

Between blindness and sight

They are delusions

Deliver us from them unruined

Shoulders on feet

Deliver us from them pure

No blood on our hands

Deliver us a thousand

Or a hundred

Or one.Lead us out naked

(pure) As we entered

No ministers no countries

No medals

Lead us out new

Like when we took to the street

A lot of kids walking

Not afraid of anyone

Deliver us now

Spare us the trial

The battle is terrifying

Spare us the trial

The battle is terrifying

Simply to have existed while the killing was taking place is difficult to forgive oneself for. A nagging feeling that it could have been prevented, but not knowing how. But how does fascism start, and where? It is not isolated to one place; it grows through us, making a monster of each of us, even if our hands were not the ones doing the killing. Thousands were killed in Rab’a in perhaps the biggest massacre in Egyptian history. A military regime wiping out its strongest opposition, Islamist supporters, while nearly everyone else stood by as silent spectators. Their deaths created a dark void that has spread amongst us.

In the initial year of the revolution, the goal was clear: social justice and dignity could only be achieved through the fall of the police state. That police state withdrew and the first military council failed to rule in 2011. Dreaming up the alternative became the difficult part. Every step became a test of faith. Having questions was safer than having answers, fear was truer than courage, and the battle became about staying true to something larger than politics, an almost otherworldly world.

One day in November 2011, I overheard a conversation between two men walking slowly towards Mohammed Mahmoud Street, where violent clashes were underway between protestors, armed police, and the military in what would later be referred to as “the second revolution.” One man said to the other, “But I’m afraid…”

“That’s totally understandable, to be afraid,” said his friend in response. He continued, “Fear and courage are not the opposite of each other. On the contrary. Remember the story of Moses? He was always afraid, but he was also terribly brave. Fear and faith come from the same place, from here…” And he pounded his chest with his fist, above his heart. His friend smiled at him as they put their arms around each other and disappeared into Mohammed Mahmoud Street.

A Struggle Sustained by the Couches of Friendship

You will see homelands being shattered,

Crowds gathering and being scattered,

the world will stare, once again, amazed,

… and then life will simply move on, unfazedSo come along and saunter in

And until you’re here and we continue,

I’ll spread love and candy for you

On our living room couch.

– from the song “Al Kanaba” (“The Couch”) by Kaharib, 2019

Memories of the revolution, or having survived it, aren’t all heartbreak. When I think of myself before those ten years (especially in the period when I was politically active, between 2000 and 2010), I remember myself as someone adventurous, more daring, when everything seemed worth it. The costs were not as high. When I think of myself now, I feel significantly embittered, but also shaped by a sense of fulfilled hope.

Between 2000 and 2010 there was a growing movement in many facets of Egyptian life: solidarity with Palestine, independent workers’ unions, support for peasant networks and the right to land, building opposition to the practice of torture in prisons, and a slowly developing and articulated opposition to then-president Hosni Mubarak.

As things developed during those ten years, it felt like the spaces that we reclaimed as “ours” were growing. And as opposition to the government grew, so too did this sense of who “we” were. With it grew a sense of solidarity, wider community, but also this realization that our role as citizens went beyond merely roaming permissible streets. Rather, we were the makers and creators of these spaces. The city was ours, and worth fighting for.

In these struggles, comrades become friends, and in the short but powerful moment of the realization of dreams, friends become family. I was involved in politics not only because I believed a different world was possible, or that I was sure it should or could be achieved. It was because I had dreamed up a world with my friends, with my family and loved ones, and we had taken to the streets, to organizing, to writing, and to creativity in order to achieve it. Without them, I could not recognize the dream.

They are the most significant aspect of this journey. And in many ways, the bond between us is one that is cemented by a dream of a possible world. A world so beautiful, perhaps, that we couldn’t have achieved it. But we were not naïve to try. We, like every group and individual that has taken part in revolutions all over the world, have been changed forever by this experience. By the experience of having been willing to risk everything for the possibility of that world that glimmered with justice. This particular moment in time has proven to us that the forces of injustice were far stronger than we were—but this moment cannot possibly last forever.

In an article written by imprisoned activist Alaa Abdelfattah about being allowed to see his newborn son Khaled in a half-hour visit, he concluded with a sentence that drew upon the meaning of his son’s name in Arabic: “eternal.”

“Love is Khaled (eternal), sadness is eternal, the square is eternal, the martyr is eternal, and the country is eternal; as for their state, it is for an hour (of that eternity), only an hour.”

Egypt has become a far more dangerous place than it was before the revolution. Torture is rampant, forced disappearances are widespread, and jail cells are brimming with youth with boundless imaginations and a sense of entitlement to a better world. Our freedoms have been significantly curtailed. But the struggles continue, and not just on the streets and against the regime. The struggles continue in resistance to a patriarchal society, in deeper forensic research into the ugly practices of the state, in journalism, storytelling, and art. The military state may have world regimes on its side, money and ammunition, jail and sophisticated torture mechanisms. But we have generations that will know the truth, the truth of that state’s evil, and the truth of boundless possibility—that possibility we had a glimpse of. For a short moment, but one with so much eternity.

In March 2020, while reorganizing my desk during the first coronavirus lockdown, I found a group of letters from my close friend Alaa Abdelfattah, sent during his various periods of captivity between 2014 and 2019. He was released in March 2019 after serving a five-year sentence for attending a protest. His release lasted mere months before he was taken in again, kidnapped and imprisoned without clear charges. Reading the letters is like having conversations with him, and his wisdom transcends the moments in which he writes. I was caught by a paragraph in a letter dated February 24, 2014.

We do need to learn to stop feeling guilty for things that happen to us though, and to let go of the sense of destiny. If we accept that constantly trying to be good and do good absolves you of guilt and that if you slip once or arrive late or whatever you don’t miss the train of destiny, our ability to love life is much greater. I now get angry when people say things like if we had stayed at the post in the square on 11th of February this or that would have happened. The notion that there is a single moment, a single choice that alone changed the course of history, is the worst kind of romanticism; it is paralyzing, inspires guilt, and invites fanaticism and intolerance. …We get 2nd chances and 3rd and 100th and an almost infinite number of chances. It wouldn’t be a struggle otherwise.

The moment is defeat; the moment is theirs; the moment is dangerous. But this moment can’t last forever. Struggle and possibility will.

[1] Rab’a al-Adawiyya is a square in the Nasr City district of Cairo where a sit-in was staged by supporters of former president Mohammed Morsi, who had been ousted by the military one month before. The predominantly Islamist sit-in was violently dispersed by the military on August 14, 2013, with at least one thousand protesters killed and more than two thousand injured. Human Rights Watch claimed this to be the largest one-day killing of demonstrators in world history.

This essay first appeared on the site of the Heinrich Böll Foundation and appears here by special arrangement.