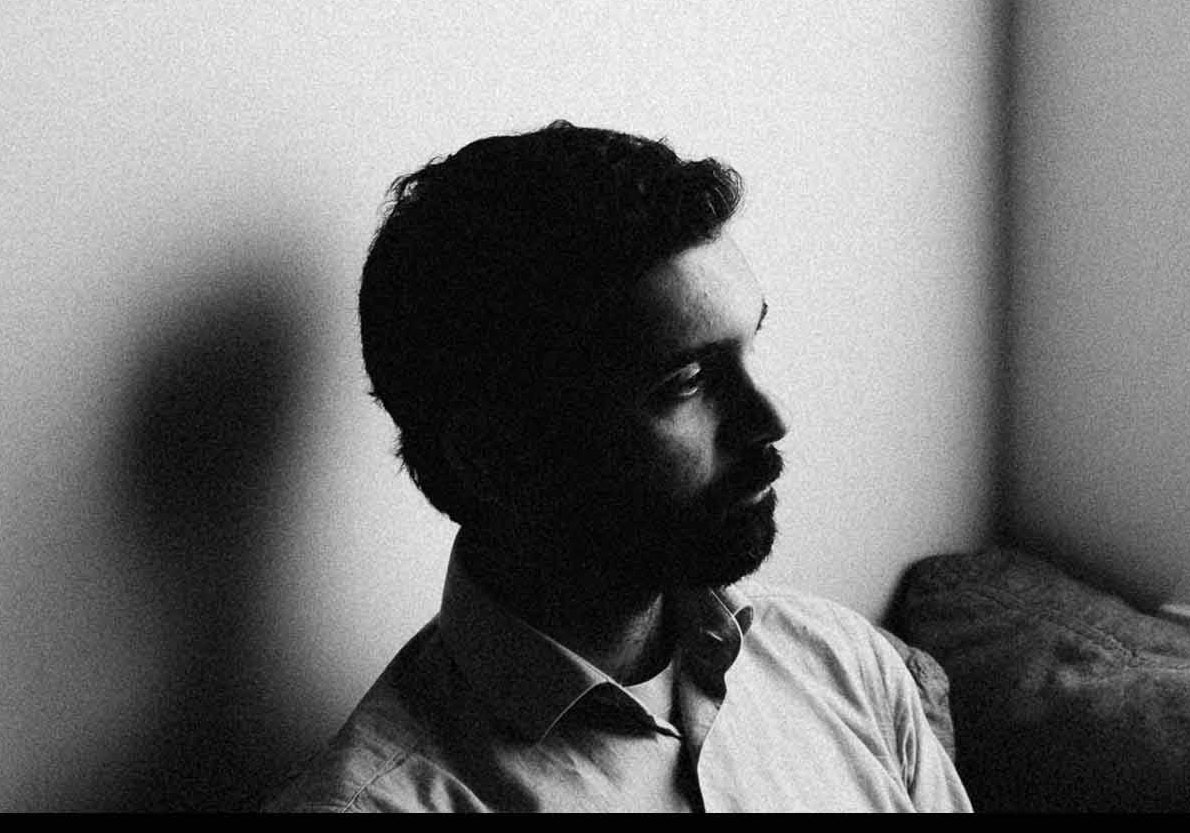

A film by Saeed Taji Farouky

Strange Cities Are Familiar will be viewable for a limited time only. We recommend that you watch this short film full screen, and give yourself time to absorb its effect, before reading the director Q & A that follows.

For Strange Cities Are Familiar, what was the particular emotion you were going for in the writing, and did that evolve as you began filming with Mohammad Bakri, who is after all, one of the great classic actors of Palestinian cinema?

I had always wanted the film to evoke a sense of atmosphere, rather than focus on a linear narrative, on the events. In all of my films I’m interested in breaking away from plot, from a linear deterministic narrative style. I don’t feel it works for me, it doesn’t reflect the way I experience life. It doesn’t capture the chaos and unpredictability of life. It doesn’t reflect the violence and fractured psyche of the world I see around me. I also feel that in relation to Palestine, a nation that is so fractured, so torn apart, subject to intolerable violence in every aspect of our lives every day, linearity, and logical, efficient plot are insufficient. So I try to make films that are about experience, atmosphere, emotion, about evoking meaning rather than describing it. This is, I guess you could say, the political reason for constructing my films the way I do. There’s also the personal reason, which is just that I don’t experience my life as a logical, efficient sequence of interconnected events, but rather as a network of impressions and the remnants of events and emotions.

With this film, I was inspired greatly by Mourid Barghouti and his masterpiece I Saw Ramallah. Although my life is very different from his, I found so much was familiar in that book. He put into beautiful words so much of what I’d felt. So I tried to evoke that experience, using events from my own life and my family’s life. The overriding emotion for me was melancholy. A suffocating cycle of fear, and relief. Of grief and love. Mourning and redemption. These are my experiences as someone who always feels he’s living in exile, no matter where I am. That was the thread that is woven through the film.

The role was written for Mohammad, and to be honest I don’t think we could have made it without him. When he came on board, he’s also someone who, I feel, has an overwhelming sense of melancholy. He’s seen a lot. He’s been through a lot. He’s always fighting. He’s someone who understands that when he feels relief, there’s still the undeniable awareness that this is only temporary and individual relief. The political reality of Palestine remains, and there’s little relief for that. So Mohammad brought with him a weight that I could only imagine. A weight I haven’t experienced in my life, dragging the character of Ashraf through life. Mohammad also brought with him the history of Palestinian cinema, and that was invaluable in my aspiration to make a new kind of film.

Can you talk about the evolution of the screenplay, and how you felt once you finished shooting and editing the film, in terms of how it evolved, or came to express exactly what you hoped it would?

Like all my stories, the screenplay started as a series of vignettes. I don’t really think in terms of story, I think in terms of evoking a particular feeling at each point in the film. The events, the plot, is really just there to help evoke these emotional experiences, or to hold them together. But once the order is there and I feel the events have the cumulative effect that I want, the screenplay is more or less fixed. I’m quite precise in what I’m going for, and although I love collaborating and working with actors, cinematographers, composers etc to try new things, I’m not someone who wants to do a lot of improvisation, or wants to play with the film a lot during filming.

The story in the end is quite delicate, for me, and needs to be perfectly balanced but always on the edge of collapsing for the film to work. In the end, I think the film was what we had hoped it would be. The most important aspect of it was that Mohammad had the space to explore his character through tiny movements, gestures, looks, without using much dialogue. And we achieved that. He said it was some of the hardest acting he’d ever done, because so much of it was internal, and non-verbal. My only regret, looking at it now, is that I would have cut even more dialogue. But what’s the saying, “a film is never finished, only abandoned.”

In this story, a son is wounded — “they shot him” — but we don’t know exactly what happened. In the wake of the killing of Palestinian American journalist, Shireen Abu Akleh, as a viewer here, I did feel we were talking about the Israeli occupation forces shooting a Palestinian bystander, protester or even a journalist. We just don’t know very much about your character Ashraf’s wounded son, Moataz.

I like ambiguity a lot in films. I like creating moments that the audience can feel have a lot of weight, a lot of history and density, even if we don’t know exactly why. I like to make scenes that are imbued with this spirit, this sense of experience and before and after, although we’re only allowed to see the now of it. So I love that you got a very specific story from that scene, even though it doesn’t explain much. And of course, the circumstances we watch a film in will always inform the viewing.

Sadly, in Palestine, these kinds of killings happen all the time. Only three weeks after Israeli soldiers killed Shireen, they killed another journalist, Ghufran Harun Warasneh. So we are constantly referring to the latest horrific murder when we watch scenes like that. This is our collective memory, and tragically our collective visual history: images of innocent people killed by the occupation. We shouldn’t exploit this, of course, but we also shouldn’t shy away from it. My personal life was also marked with constant and spontaneous violence, so it’s something I write into my films as a memory, as a representation of interior psychology, as a shock. The scene isn’t “real” in the world of the film, but it’s real to Ashraf. We all have these scenes that are real to us even if they only exist in our memories.

Ashraf appears to be lost in London, even before he receives word that Moataz has been shot. That news propels him into a tunnel of memories, with a woman named Souad who is a refugee with a baby, and Ashraf recalling himself as a soldier “in two wars.” What do you hope viewers will take away from this film?

I always try to construct my films in such a way that everything feels slightly off-balance, it doesn’t quite make sense, until the very last moment. At that moment, there should be a sensation that draws everything together. It’s not explained, it’s not the end, it’s not the traditional “climax,” it’s not the conclusion of a plot, but it’s a goodbye. I always remember goodbyes — the feeling, the mixture of relief and guilt, the sensation that lingers with you long after the person is gone. That’s how I want my films to feel. That they remain with the audience like a memory. The exact content of that memory isn’t so important for me. I think many people can watch that film and feel it reflects something about their lives — exile, loneliness, friendship, community, despair, relief, whatever it might be. My personal experience that I wanted to reflect in the film was this: the moment we realize we need to find comfort, consolation from our grief, and that comfort needs to come from someone else.

As a Palestinian filmmaker in London, you’re part of a vast diaspora. I’ve always wondered how it is that growing up and/or living abroad in another country and language not only doesn’t extinguish Palestinian identity, but seems to strengthen it.

Yes, that’s very true. I also come from a home where Palestine wasn’t emphasized very much. I think my father’s priority was to give us a stable, ordinary life without any of the trauma he grew up with. But it’s not unusual for the refugee to want to bury their experience, while their children begin the process of digging it up. So that’s where I am now, digging it up. There’s also a very explicit political agenda for me in this kind of work — that is, to challenge the Israeli narrative that we don’t exist. Our culture is a hammer that can shatter that lie. Our cinematic history is also a very literal victim of the occupation because our film archive was stolen when the Israelis retreated from Beirut in 1982. It still hasn’t been returned to us. So every Palestinian filmmaker is not only creating a new visual culture, but is filling in the void left when ours was stolen. This is a very powerful mission, and something that I think keeps us going, keeps us inspired.

More broadly, when I look at the work being produced about Palestine — even sometimes by Palestinians — it’s often superficial, over-simplified, propagandistic, trading in tired cliches. We have to move beyond that. We have to create a new cinematic language that can communicate our experiences, so creatively there’s also a very strong compulsion to re-connect with Palestine in order to better understand how to communicate it. I’ve been immersed in Palestinian folklore for around a year now, doing research for my next film, going back to our earliest stories to learn how to move forward with our narratives. So I need to genuinely engage with Palestine in a very profound and vigorous way, deconstruct it in order to learn how to reconstruct it. I always keep in mind that when we create art, we’re part of the mission to build a state because what is a state but the cumulative memory of our shared culture.

—Jordan Elgrably

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)