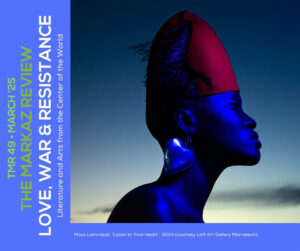

Aomar Boum, Guest Editor, TMR

I am not an artist or expert of al-qissa al-muṣawwara (graphic novel/comic book) or bandes dessinées (BD). I do not draw and never attended a school of art. However, I have recently become interested in graphic novels as a medium of writing. In fact, I am currently collaborating with Nadjib Berber (see his bio in this special issue) on a graphic history of European and Jewish refugees held in Vichy camps in North Africa during WWII, based on the archives of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Although my interest in graphics and comics as a mode of writing is pretty recent, I was exposed as a child to a pop culture of BD while growing up Morocco. My pastime after school was limited because I lived in small Saharan village. However, I moved to Marrakesh to live with my oldest brother in the late 1970s and early 1980s. My brother did not own a television set at the time, so I had to improvise to spend my spare time. One of my early evening rituals was to sneak out of our house and join my neighbor’s son to watch the Japanese anime Grendizer, Goldorak and Captain Majid (Captain Tsubasa). Missing the series was never an option. With the success of both shows on national TV, they were serialized and translated in comic book magazines and sold on newspaper stands and in book shops. During the same period my brother signed me up for the nearby French Cultural Center, just a few miles from the mellah of Marrakesh. It was there I was introduced, like many young readers of the generation, to Les Aventures de Tintin (Adventures of Tintin) and to Asterix the Gaul. Both the dubbed and serialized Japanese series and the French comics were at the center of the popular culture in Morocco at the time. While French comics dominated the cultural scene, the existence of Arabic translations allowed us to also read the Arabic versions of Goldorak, Bissat al Rih and Tarzan, which we circulated among us children.

For decades Morocco has been an importer of comics. While there was no shortage of graphic artists educated mostly at the École des Beaux-Arts in Casablanca and the Institut National des Beaux Arts in Tetouan, consistent institutional and national support for local production, publication and distribution of comics within and outside Morocco was absent. Therefore, readers had to rely on foreign production, which limited the market largely because of language access between Arabic and French and, oftentimes, due to the expensive prices of the books. This Moroccan story is general to the rest of the Arab world and the Middle East, where there is a lot of potential for a homegrown comic tradition but where institutional and financial support is hard to find.

Lack of institutional and financial support is compounded by censorship and incrimination of cartoonists. State authorities have for decades censored cartoonists and even went as far as accusing some of them of blasphemy. Artists and political cartoonists could not caricature state leaders in the Middle East and North Africa without being arrested and jailed. The cultural norms against caricaturing religions also limit artistic representation even when artists try to avoid crude representations. Editors of newspapers and publishers avoid forms of expressions for fear of closure, fines or prison. For example in 2008 and before the so-called Arab Spring, Magdy El Shafee published Metro: A story of Cairo, a graphic novel that exposes injustice, poverty and corruption in Mubarak’s Egypt through the story of Shehab, a young software engineer who steals to pay off his debt. El Shafee was jailed for offending public morals and his graphic book was banned. This trend continued even after the Arab uprisings in 2011.

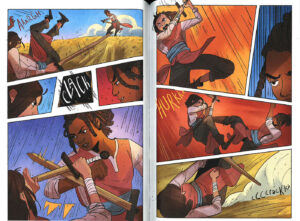

This TMR special issue on comics in the Middle East and North Africa is an attempt to recognize the work that has been done by Middle Eastern artists in recent decades. We have tried to assemble a list of representative albeit non-comprehensive contributions from different experts as well as biographies of native artists from the region, to provide a glimpse into a very vibrant field of literary and artistic expression. This issue is also an opportunity to assess what Maghrebi and Middle Eastern comic artists and writers have achieved. Despite the long history of official restriction on graphic and comics, young artists have worked under strenuous conditions before experiencing a moment of liberation in the aftermath of the Arab uprisings in 2011. While the return to authoritarianism lingers on the horizon and despite Maghrebi and Middle Eastern authorities’ maintenance of a set of religious, social and political redlines that artists of comics, graphic novels and cartoons avoid for fear of jail, comics have gained both importance and readership.

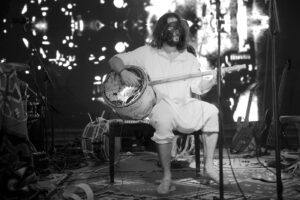

In this special issue, we cover general trends in the Middle East and North African comics over the last 20 or 30 years through a historical piece on Arab comics by George “Jad” Khoury. Sherine Hamdy, one of the leading anthropologists of the Middle East who has pioneered the use of comics as ethnography, highlights the role of Middle Eastern women in comics-making. Susan Slyomovics, a leading expert of visual anthropology in the MENA region, acts as a translator and introduces us to Nadjib Berber and Menouar “Slim” Merabtene, two cartoonists from Algeria, whose stories demonstrate the challenges of being an artist in the region, struggling to adjust to the political and economic realities of comics-making.

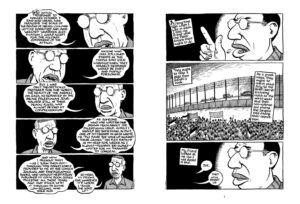

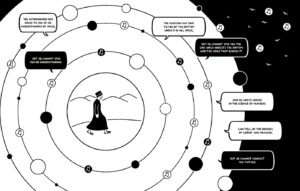

Contributions by Amber Sackett, Brahim El Guabli, and Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik, respectively a graduate student of Francophone studies, a literary scholar, and a historian, provide diverse readings of the different ways comics engage issues related to archives, history, and memory in both colonial and post-colonial settings in the region. These contributions, which cover Algeria, Morocco, and Mauritania demonstrate the richness and multilayered roles the comic medium plays in societies’ lives. Jenny White walks us through the process of producing a comic using ethnographic data on modern Turkey. My article sheds light on the collaborative work of Abdelaziz Mouride, the dean of comics in Morocco, and his attempt to mentor and train a new generation of Moroccan comic artists by focusing on his work on the challenging issues of illegal migration and human rights abuses that continue to haunt the region. And siblings Sherif and Hanna Dhaimish share the story of their father, the late Hasan “Alsatoor” Dhaimish, a Libyan cartoonist in exile in England.

There is a growing positive attitude in the MENA region towards comics as a viable means of knowledge production, self-critique, and democratization. The number of independent artists, comics magazines, and local companies publishing graphic novels is on the rise. This increase in comics has led to the emergence of specialized festivals that advertise the work of these Middle Eastern and North African artists throughout the region. This local work has also translated into international interest through translation and global circulation of works that were originally published in the Middle East and North Africa. Counterintuitively, many artists have opted to stay in the region and instead of exile to the West, despite the occasional crackdown on their colleagues who engage in the critique of state’s human rights, political and social records. This choice has allowed them to create more laboratories of art where they transmit their artistic knowledge and know-how to future generations of young Middle Eastern and North African artists, who will be able one day to represent the themes and issues of their region in their language and artistic sensibility. Comics have been anchored in the region, not just as a practice, but also an intelligent and subtle way to nuance both local and global issues.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)