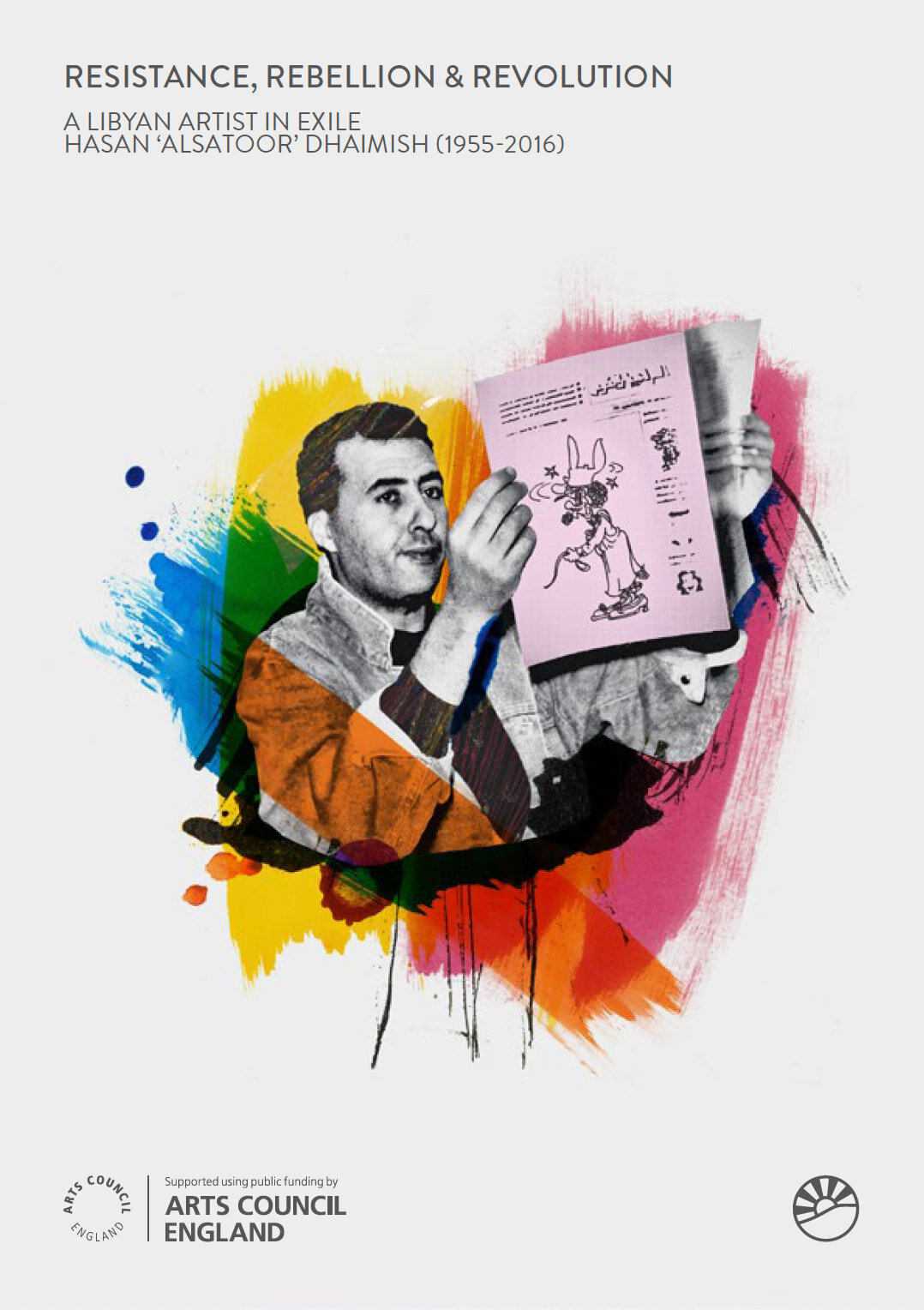

The authors are co-curators of the exhibition Resistance, Rebellion & Revolution, which runs from 19 to 29 August, 2021 at the Hoxton 253, an art project space, 253 Hoxton Street, Whitmore Estate, London N1 5LG. Click here for exhibition hours.

Sherif and Hanna Dhaimish

Our father Hasan Mahmoud Dhaimish was born in the al-Shabi district of Benghazi, Libya, in 1955. He spent the first 20 years of his life in the east of Libya, and then gave into his desire to travel and explore the world. He arrived in England in 1975 and in the late ‘70s, he arrived in Burnley, Lancashire.

It wasn’t long until Hasan created Alsatoor — the pseudonym under which he began publishing anti-Gaddafi satire. This persona followed him through the decades. Along the way, he became a husband, a father and a teacher.

Four years prior to his birth, Libya had become an autonomous kingdom following hundreds of years of colonization.

Libya’s east where Hasan grew up, often referred to as Cyrenaica after the ancient Greek city of Cyrene, has often been on the receiving end of injustice and the birthplace of rebellious movements, including The Lion of the Desert himself, Omar Mukhtar, a Libyan icon of resistance and national hero to many, who fought against the Italians until his capture and execution in 1931.

When Hasan was born, King Idris was on the throne. He had shifted Libya’s central power from today’s capital Tripoli, to the eastern city of Tobruk, which sits on the Mediterranean coast, 100 miles from the Egyptian border. Hasan’s father, Sheikh Mahmoud Dhaimish was appointed as the religious adviser and imam of the King, so he moved the family to Tobruk for two years.

“I was politically aware at an early age, thanks to my father. He played a fundamental role in forming my ideas. I inherited the spirit of rebellion and not to be afraid to speak the truth and stand with the weak from him.”

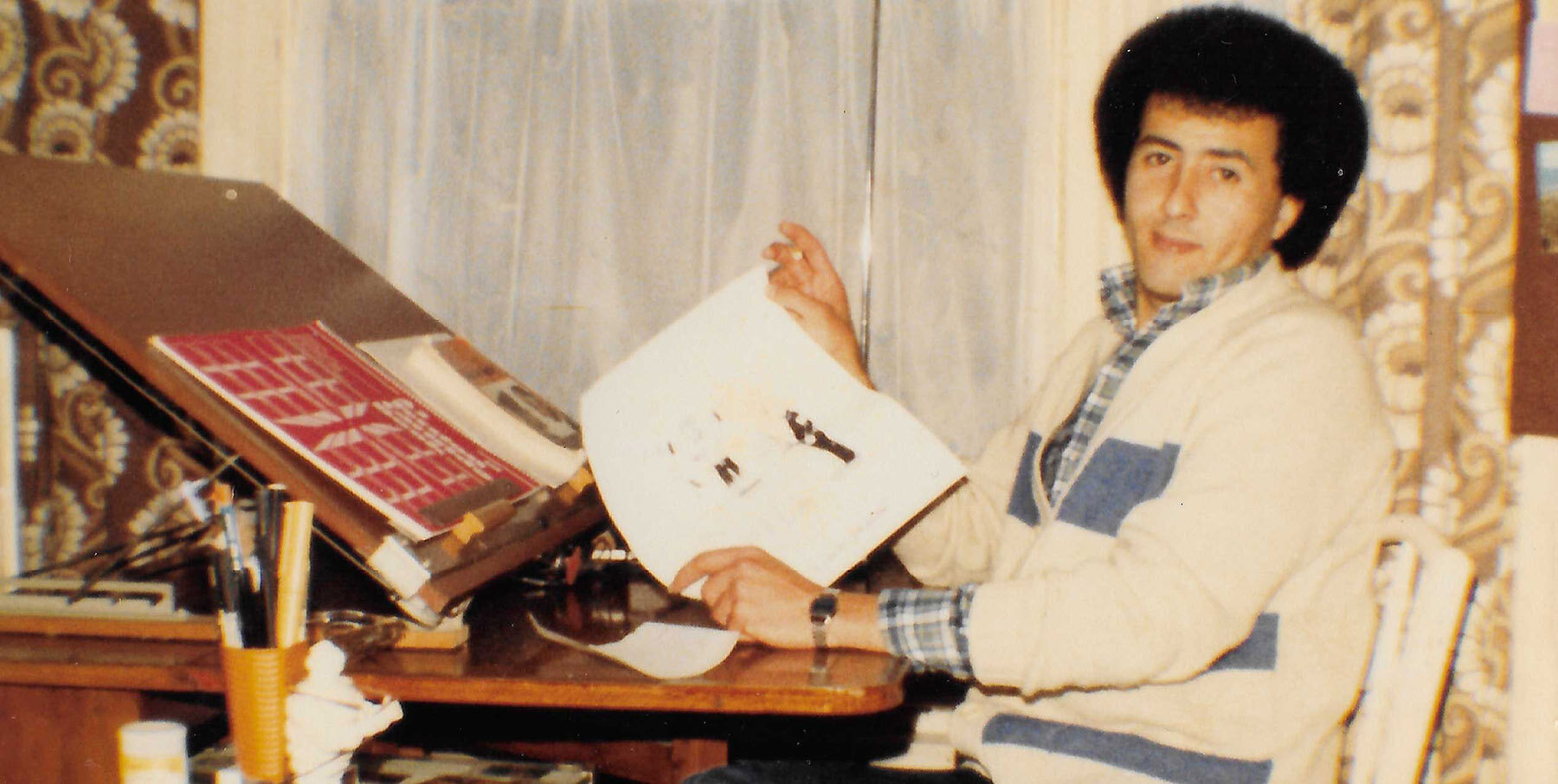

As a young child, Hasan would watch his father draw pigeons on the roof tiles of their home where the family kept the birds. He would draw a single pigeon on each tile, while explaining his technique.

Sheikh Mahmoud also introduced Hasan to the famous Libyan artist, Mohammed al-Zawawi. They would study his style and discuss his satire, often bursting into fits of laughter. Noticing an eagerness to learn about art, his father was keen to share anything related to painting and politics, laying the foundations for Hasan’s life ahead. He soon started drawing caricatures.

“I remember my sister, who was also my best mate, getting engaged. I was angry about it, so I started drawing cartoons of her on the walls of our home. I never got in trouble, though. I think my dad saw I had talent. After that, I started drawing pictures of Gaddafi in my room. Soon afterwards, my brother-in-law found them and took them to local security forces. ‘Are you out of your goddamn mind?’ I asked him. I was furious, but he said they had a good laugh at them, too, so there was nothing to worry about.”

Art meant something to Hasan from a young age. It was a way to channel both his rebellious nature and curiosity.

“At that time, I didn’t realize that art chooses you, not the other way round.”

He wandered the streets and souqs like al-Jarida and al-Zalam, where he would smell the scents emanating from the stores and admire the colorful fabrics being sold around him, all of which would play a role in his art later in life.

“I used to spend time playing on the beach of al-Shabi. I would watch the ships while they disappeared beyond the horizon. I always wondered, where did they go? I was eager to know what existed beyond the sea. I used to imagine foreign cities and their people. The idea of travelling was stuck in my mind since childhood. I imagined myself building a boat and sailing away. Living on the edge was a part of me because of the sea.”

Like all young Libyan men in the early 1970s, he had to do national military service. He completed his stint under an invisible cloak, receiving little attention from generals and corporals. “Dhaimish, eh? Where’ve you been hiding?” one commented whilst he was being discharged. That same cloak would come in handy over the next few decades. Hasan was about to leave Libya behind forever, and turn his paintbrush into the ultimate weapon of social and political dissidence.

From Benghazi to Burnley

In 1975 at the age of 19, Hasan arrived in London with no intention of staying. Like many who left Libya in the ‘70s, he believed Gaddafi would soon be deposed and that he would return to the warmth of North Africa. Stepping into cold England wasn’t exactly what Hasan had envisioned — but the country soon became his playground.

He’d run wild at reggae festivals, discos and psychedelic parties, enjoying life without so much as a pittance in his pocket, while dodging all calls to return to Libya like bullets. His deportation was inevitable, but in the meantime, he drifted to Bradford, Yorkshire, and then made an impromptu journey to Burnley, Lancashire.

“I was in a cafe with some Libyan friends, and was introduced to a guy called Sa’ad. I asked him where he lived, and he replied, ‘Burnley.’ I’d never heard of the place, but after he assured me there was a college I could enroll in, I put my record player and rucksack in his Morris Minor and took off. Next thing I knew I had been in Burnley for 35 years.”

He’d gone from Benghazi to Burnley via Yorkshire. It was a case of life being stranger than fiction.

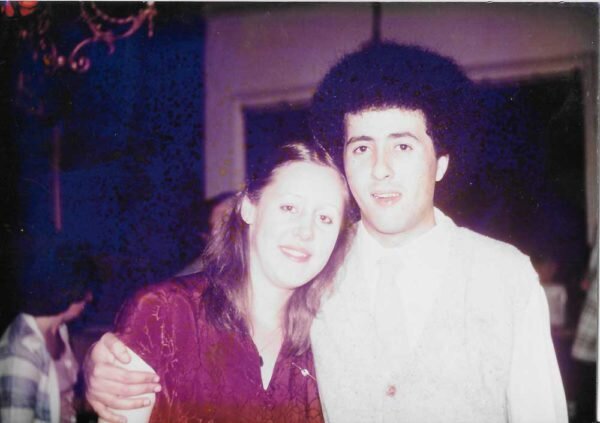

It was here where he met Karen, whom he married in 1979. Karen was born and raised in Brierfield, a small town next to Burnley. At the time she worked as a graphic artist.

“He was going to be deported on the Monday because they wouldn’t grant him political asylum — the government sent a letter stating the time he had to be at Manchester Airport,” Karen explained. “So we got married on the Saturday just before. God knows what would’ve happened to him if he had been forced to return.”

Hasan was living like most 20-somethings do — young, wild and free. But he lacked stability until he met Karen. He once said:

“She’s been my rock since day one. I wouldn’t have made anything of myself if it weren’t for her. She stuck by me through all the turbulence.”

And turbulence there was. Hasan was monitored closely by authorities due to the circumstances, but he now had a partner in crime. Karen helped Hasan pick up English, something he did quickly. He would buy the Guardian daily and read it cover to cover, quizzing his wife on words he did not know, then practiced working them into sentences.

They were a couple of young creatives whose love and friendship for each other formed a bond that would last a lifetime.

The Birth of Alsatoor

On a trip to London in 1980 with Karen, Hasan spotted an Arabic newsstand outside Earl’s Court tube station.

“An orange magazine called Al-Jihad caught my eye from afar, so I went over, picked it up, and realized it was for the Libyan opposition. It was about four pages with no contact information. I wanted to get involved with my cartoons. Luckily, the bright blue magazine next to it called Al-Sharq Al-Jadid had exactly the same articles inside, along with contact information. I bought both, took them back to Burnley with me and wrote to them. The only contact number I had belonged to my in-laws, Jack and Enid.”

A couple of weeks later, Enid arrived at the couple’s flat. “A Frenchman called for you and left his number.” Of course, the man wasn’t French at all — he was Libyan, and it was Dr Mahmoud al-Maghrabi, the first prime minister of Libya after Gaddafi’s 1969 coup.

Hasan joined the opposition without any hesitation and began sending them caricatures of Gaddafi and his associates, which were received with adulation from readers and fellow members.

“Dr. Mahmoud al-Maghrabi was like a teacher to me. He taught me patience … Another inspiring person was Fadel al-Masoudi [Libyan journalist and dissident], who taught me a lot about journalism and satire … there are more, but these two figures left a mark on me.”

Between 1980 and 1985, he produced cartoons for Al-Jihad and Al-Sharq Al-Jadid and also began attending rallies including the infamous event where PC Yvonne Fletcher was shot dead outside the Libyan embassy on St James’s Square, London, in April 1984.

As the only Libyan for miles around in Burnley, Alsatoor was able to operate covertly and blend into his new hometown as best a foreigner could. He was well aware of the dangers his work posed for him and his family back in Libya, but also for his family in the UK.

Between 1980 and 1987, Amnesty International reported 25 assassinations of “stray dogs” by the dictator′s international death squads. “It is the Libyan people′s responsibility to liquidate the scum who are distorting Libya′s image abroad,” Gaddafi warned dissidents. As his work began to grow in popularity, Alsatoor remained an anonymous enigma within and outside Libyan borders; a mysterious persona that was the product of a slick pseudonym and a keen awareness of the risks.

Go out into the world and if any Libyan crosses you, kill them.

The US and Libya were in the process of improving relations at that time.

Anwar Sadat- ‘A bullet?’ Yasser Arafat – ‘Poison?’ Saddam Hussein – ‘Choked?’ Gaddafi – ‘Misrata!’

Gaddafi’s wife Safia catching him heading to the nurse’s room during the night.

Gaddafi was never one to fight fair.

Gaddafi the ghoul is dead at last.

Exile in the ‘80s

Six months after the shooting at the embassy in 1984, Hasan became a father to his first daughter, Zahra. He was working at Carlo’s Italian restaurant in Colne at the time. Hasan had embraced family life in northwest England, as the distance between himself and Libya continued to grow.

He didn’t join any other anti-regime movements, as he was convinced that they were unable to change or effect serious change in Libya. Instead, he had established Alsatoor as an independent voice. As the Libyan opposition entered a phase of stagnation, Alsatoor began publishing his own work criticizing Gaddafi and opposition parties.

“I knew then that cartoons were a powerful tool and had a stronger impact than I had ever imagined.”

Burnley and Pendle, Lancashire, once stood at the heart of the cotton production and engineering industries. In the 1980s, parts of northern England had become an industrial graveyard under Thatcher. Pakistani immigrants who came to reboot the textile industry during the 1970s and ‘80s were living in the area, but there was a general lack of integration, an issue that still exists today. Mix all of this together, and you have one of Britain’s most deprived areas, albeit surrounded by beautiful countryside.

Hasan was never victim to race attacks, but he often spoke of the systemic racism that existed at the time. Intimidating immigration officers would often pay him random visits, even after he was married. Before that, he was treated with hostility by authorities despite the obvious danger of returning to Libya. But, it never phased him, and life continued.

Education, Education & Artistic Exploration

In 1991, Hasan passed his driving test, which opened a world of possibilities and gave him the confidence to return to studies. He enrolled on a computer course at Nelson and Colne College.

“I was in a classroom in front of an Amiga computer. Everyone was typing while I just stared at the screen not understanding what I was required to do. I found a program with a brush and colours, so I started to draw.”

This is how Hasan kept himself occupied for the first few classes. Will Barton, who worked at the college, told him he should enroll as an art student. Hasan was confused, he thought he’d be kicked out of class for not following the task. But instead, Will offered Hasan a letter of acceptance to the college, and as a result he received a grant from Lancashire County Council to help him through his studies.

“I was scared at first — I didn’t know what would be required of me. I could draw simple caricatures, but studying fine art is something else.”

But he pushed on and became more motivated than ever. He finished his A-Levels and then went on to Bradford University to study for a BA in illustration.

After the birth of his and Karen’s third child, Hanna in 1993 — sister to Zahra and Sherif (born in 1988), he was close to graduation after cramming six years’ worth of studies into just four. His time at college and university was spent around other creatives, which influenced his own artistic style. And then in 1996, he began his teaching career at Nelson and Colne College.

In the evening, he’d paint to the sounds of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Dexter Gordon, or Blind Wille Johnson and Skip James, bringing jazz and the blues to life through his artwork.

“I moved away from satire and switched to painting, using music of Black Americans and their social history as inspiration. I loved jazz because of its melody and the conditions from which it appeared. I identified with the history of Black people in America, based on my own suffering and persecution.”

In 2002, he joined the social site Deviant Art under the username ‘Alsature’. His work was far removed from the satire he was producing elsewhere. It was a space to experiment and create art for a different audience. It was a breathing space away from the political sphere full of funk and color.

In the early 2000s Hasan found the aforementioned The Story of the Blues by Paul Oliver in a skip near his Brierfield home. This book changed his life. Oliver’s pictorial history of the 20th century’s most influential musical form introduced him to artists such as Blind Willie Johnson, Blind Willie Pep, Skip James and many more who pioneered the Mississippi Delta sound. Hasan had gone back in time; his haphazard genre-hopping matched his unorthodox approach to almost everything.

England had become his home away from home. But there was always the feeling of being in transit, belonging to neither here nor there. Music helped bridge the gap between head and heart.

Digital Age

At the turn of the millennium came the rise of the internet — a pivotal change that would make Alsatoor’s work globally accessible. He was doing some illustrations for a software and web development company based in Pendle called Subnet, and that’s where he got his first email address. At the time, around 2000, he didn’t have access to the internet at home.

“Someone called me from Subnet, and told me I’d received my first email after they had created a website for my paintings. It was from Dr Ibrahim Ighneiwa, who asked me for permission to add my site to libyawatanona.com, which I accepted.”

Hasan then got the internet at home and soon realized the real potential of Alsatoor. He spent hours alone listening to jazz and classical music. They were his companions on the long British winter nights spent in front on the screen.

Hasan’s studying didn’t stop. He would read up on artists, taking a particular interest in Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pablo Picasso, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, all of whom influenced his own work.

After the teaching day was finished, Hasan became Alsatoor. He would glue himself to his desk, observing Arabic news stations that were picked up from an array of sketchy satellite dishes on the side of the house.

Illegal access to Libyan news channels revolutionized Alsatoor’s work, as he could now rip sound and video straight from the TV and manipulate them. He would watch the Libyan national Al-Jamahiriya channel with access to Gaddafi’s rambled speeches.

“It was an effective method in my fight against him. I would get complaints from Libyan authorities on my YouTube channel later on, but it didn’t stop me. I was constantly being targeted, as I never set myself limits. People would complain that Alsatoor had exceeded the limits of morality, and they demanded I deleted my insulting cartoons of Gaddafi and his family, but they were to no avail.”

During the 2000s, Hasan’s family members were harassed online via Facebook and email hackings, and threats were sent directly to his children. But none of this dissuaded nor frightened Alsatoor; if anything it spurred him on.

In 2003, Libya Al Mostakbal was launched — a pro-democracy Libya news site run by Hasan Al-Amin. This provided another platform for Alsatoor, with Libyans all over the world becoming followers of his work.

In the years building up to the Libyan revolution, Hasan published his work online through his own blog: alsature.wordpress.com. Just like when he started publishing works independently in print in the 1980s, it was here that he had full editorial control. This, however, was on a global scale. His work was often so offensive and relentless that other outlets like Libya Al Mostakbal refused to place them on the site.

It was a tough time for Hasan. He battled with depression and the loss of his father in 2009 drew him into a dark place. He had been away from Libya, his home, his family, for 34 years and there was no sign of change anytime soon due to the path he had set out on, and the real dangers that existed for dissidents stepping foot in Gaddafi’s Libya.

But despite everything, Hasan was prolific with his paintbrush, both as Alsatoor and on the canvas.

Revolution

In January 2011, the Arab Spring began to sweep across North Africa and the Middle East. People were demanding change in countries that had autocratic rulers for decades. Libya broke out into civil war in February, altering the country’s future forever.

Alsatoor was working at his home in Brierfield from the moment he returned from teaching at his new workplace, Craven College, Skipton, until he went to bed in the early hours. He would sketch whilst on the phone, watching TV and researching online. His blog was overloaded with posts, photos and information people were sharing with him. He was doing his best to operate as a pro-revolution news outlet, and it worked, as shortly afterwards the newly-established Libya Al-Ahrar TV asked him to join them in Doha, Qatar, and work for them.

Alsatoor, hesitant to leave his job and wife behind, knew this was his calling — his chance to join like-minded Libyans and have his work broadcast. Like many others involved in the channel, he worked around the clock to deliver news to the masses around the world who were following Libya’s fight for freedom.

In October 2011, Gaddafi was captured and killed in Sirte and the whole world watched. The man he had observed from a distance, the dictator who had been the subject of his work, the source of his woes, the reason he left his family behind in Libya, and the reason he left his family behind in the UK, too, was now dead.

The work didn’t stop there for Alsatoor; if anything, the new state of chaos in Libya was far more demanding due to the political complexities. He began churning out cartoons, criticizing political players from all angles. The form of his work had changed, but his message had not — no one escaped Alsatoor.

Even though Hasan had pledged to stop drawing Gaddafi once his regime fell, his daily publications continued to criticize Libya’s debilitated political landscape, and those who chose to enter it. From those in parliament, Western diplomats and politicians, to religious figures and journalists. As sociopolitical issues flared up across the country, Alsatoor watched on like a hawk.

Subsequent years saw a string of events rip Benghazi apart — the attack on the US consulate, and a long string of assassinations of civil rights activists and army officers. Alsatoor would always honor the fallen through his art published online, expressing solidarity with people whose lives were lost in the fight for freedom.

Doha sucked the creative spark from Hasan; he tried painting in his hotel room where he lived, but he claimed that Qatar provided him with little inspiration. He wanted to return to the UK, but he gave into the demand for Alsatoor, and in reality the money was too good to turn down.

During his final years, his artistic flair was subsumed by Libya’s poisonous political landscape. But this could also be considered Alsatoor’s golden era — Libyans could freely discuss politics and air views across social media, making his work live, interactive, relevant. He corresponded with people online, and surrounded himself with those he respected and trusted.

One of those was Omar El Keddi, a Libyan writer who many initially believed to be Alsatoor.

“He was a wonderful, talented man. I started giving him ideas for his cartoons, and he often put my name under Alsatoor. Many people started thinking I was him! I remember when I published my own name after the revolution, and Alsatoor’s response was, ‘OK great, they’ll kill you, not me.’ I miss him so much.”

In 2014, Hasan left Doha after three years and returned to the UK. Libya Al Ahrar TV had become a mouthpiece for Qatar and Alsatoor didn’t suit the outlet. He continued producing work, but was in limbo as to whether he should return to teaching or focus on Alsatoor. The latter seemed like the most sensible option as the momentum was already there.

A year later he went to Amman, Jordan, to work for the newly-founded news station, 218TV. He didn’t want to leave his family behind for a second time and return to the Middle East, although Amman seemed like a place that offered more to Hasan than Doha ever could. Sadly, he fell ill while working there and had to return to the UK in the following days.

Back in 2012, asked about his return to Libya, Hasan had told the Huffington Post, “I wont go back at the moment. I want perfection. I want democracy.” He fought for a free Libya until he passed on the 12th of August, 2016 aged 60. Alsatoor never got the opportunity to return to Libya after leaving over 40 years earlier.

Sherif Dhaimish is a publisher and curator, and Hanna is a curator and agent in the fashion industry. They were born and raised in Pendle, East Lancashire, and are now based in London.