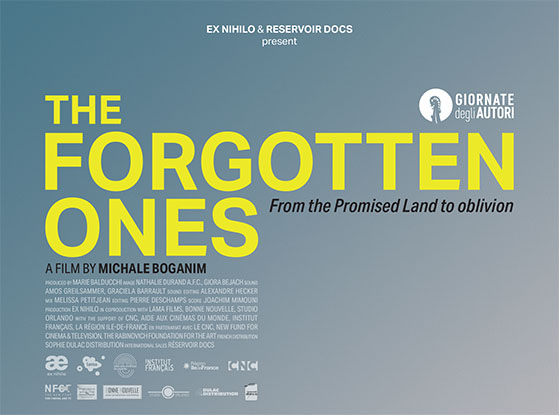

TMR reviews a film on discrimination in Israel and the original Jews of the Middle East and North Africa. The Forgotten Ones screened in October’s annual CINEMED festival in Montpellier and screens in the DOC NYC Fest on 11/09 (press screening), 11/14 and 11/15. More info.

Jordan Elgrably

You would think, logically, that people who have endured racial bias, xenophobia and persecution would be less likely to themselves become racists, just as you might expect that adults who were abused as children would not become abusers. But alas, logic plays a debatable role in the discussion of both racism and child abuse.

It has been estimated that 30% to 40% of people who are abused as children go on to become abusers themselves. And according to a study by the UK’s Office of National Statistics, up to 51% of adults who were abused as children experience or perpetrate abuse later in life.

While I’ve found no studies that reflect the percentage of racist behavior by those who have experienced racial bias themselves, it is clear that being the victims of racism has far more profound effects on a group of people than many of us perhaps realize. For instance, an Emory School of Medicine study found that brain scans of Black women who experience racism show trauma-like effects, putting them at higher risk for future health problems.

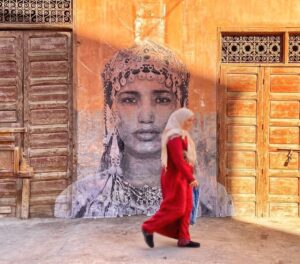

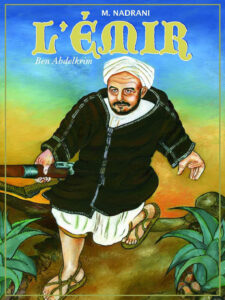

Recently, Israeli-French filmmaker Michale Boganim asked herself whether the historic Ashkenazi Jewish discrimination in Israel against Jews from Arab/Muslim lands continued to plague the country. But when Israelis assured Boganim that anti-Mizrahi bias was a thing of the past, she decided to go explore the truth for herself. The result is her third feature-length film, Les Mizrahim, les oubliés de la Terre Promise, or in English, The Forgotten Ones.

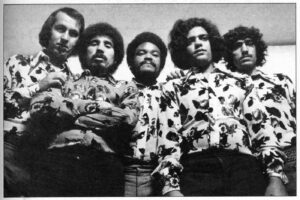

Her original inspiration for asking this uncomfortable question—after all, you would expect that the very people who suffered the Holocaust would be the last people on earth to evince racist behavior—was her father, Charlie Boganim, a Moroccan-born Jew who went to Israel in the 1950s as a youth with his family, and who later became one of the leaders of the Black Panthers of Israel, a left-wing group of Jews from Arab countries including Yemen, Iraq, Morocco, Algeria and Syria, among others.

As Boganim tells it, “My father…was shocked by the difference in treatment reserved for them. He arrived with the hope that ‘all Jews would be brothers in the Promised Land.’ The racial issue and the geographical discrimination affected him a lot after his arrival. But he reacted to it and refused to be sent to one of the border towns.”

Charlie Boganim would eventually weary of the fight against indecent treatment and emigrate to France with his family in 1984.

Born in Haifa, Michale Boganim spent the early years of her childhood in Israel. She heard stories from her father about being shunned by the European Jews who had arrived in the country before him and held the reigns of power. In the film there are many personal testimonies that lay bare the truth of discrimination. We learn, for instance, that the father of poet Haviva Pedaya struggled for years to get work, until after the June 1967, Six Day War, when he suddenly found himself in demand as an Arabic translator.

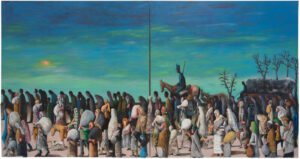

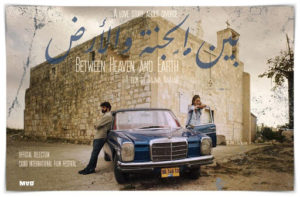

Michale Boganim went on the road with her camera crew and interviewed three generations of Mizrahi or Arab Jews in a number of locations across Israel, particularly dusty development towns in the Negev including Yeruham, Dimona and Beersheva. She also captured interviews with the great Erez Biton, the blind Algerian-born poet of the Black Panthers generation; founding Israel Black Panthers member and leader Reuven Abergel; and Neta Elkayam, a talented Israeli vocalist who grew up surrounded by Hebrew and Arabic, but sings primarily in the latter, paying homage to her family’s long history in Morocco.

The filmmaker also interviews many everyday people, including a Moroccan Israeli who uprooted himself and returned to Morocco as an adult, where he proclaims his happiness to be living in his country of origin.

The first generation of Jews arriving from Arab lands experienced perhaps the most discriminatory treatment by Zionist authorities. Resettled with their families in poor border towns facing Israel’s Palestinian, Jordanian, Syrian and Egyptian enemies, the men were used as cheap, disposable labor, and shockingly, some women had their babies snatched from them by authorities. Boganim interviews a number of Jewish wives from Yemen and other Muslim-dominant countries whose babies were mysteriously disappeared by hospital officials, most never to be found again—a conspiracy in which poor immigrants were told their newborns and infants had died suddenly while in the hospital’s care, and quickly buried, but were given to adoption agencies specializing in barren Ashkenazi Israeli families. Known as the Yemenite Children Affair, “According to low estimates, one in eight children of Yemenite families disappeared. Hundreds of documented statements made over the years by the parents of these infants allege that their children were removed from them. There have been allegations that no death certificates were issued, and that parents did not receive any information from Israeli and Jewish organizations as to what had happened to their infants.”

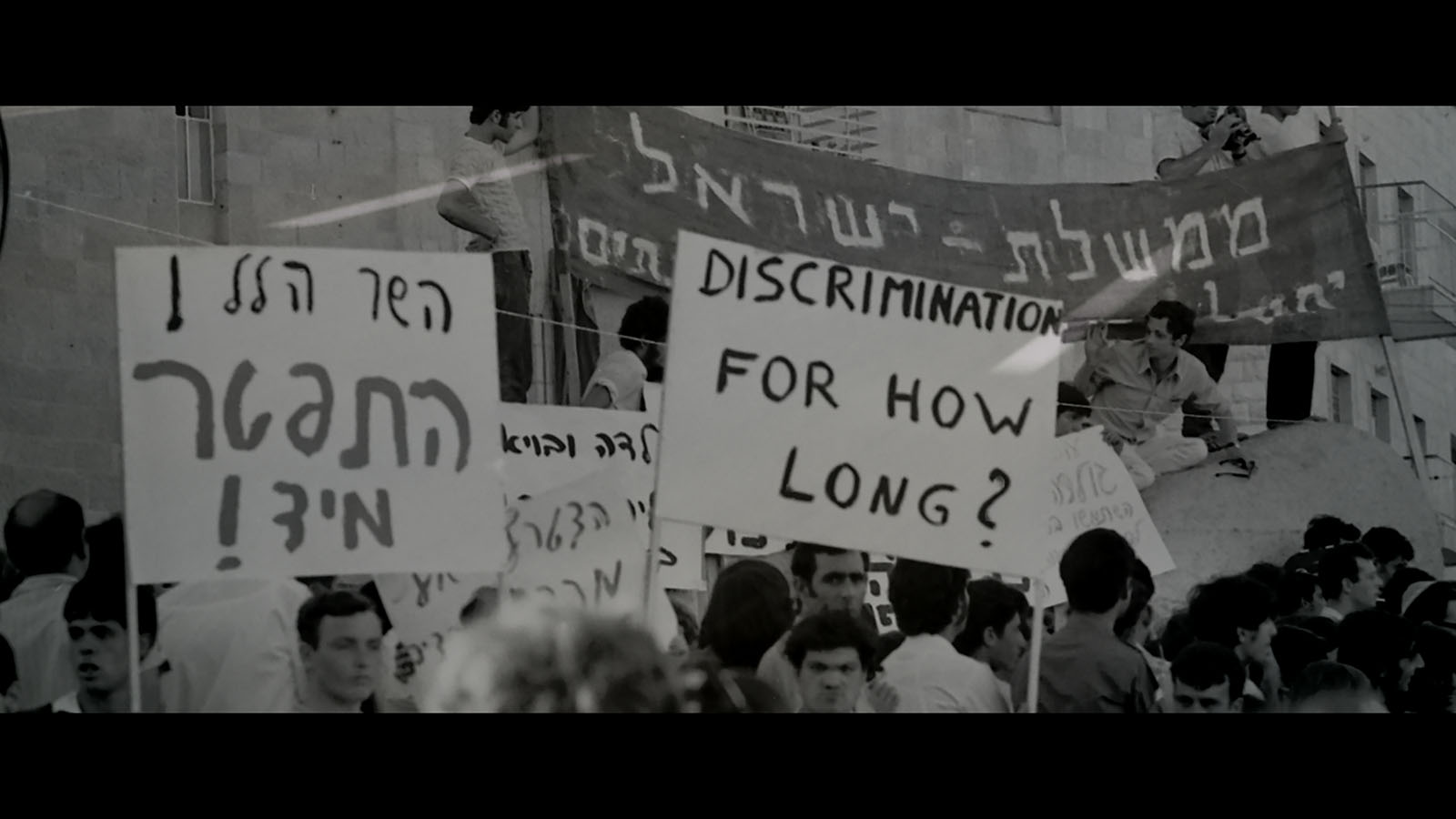

It was the second generation of Arab Jews who began to organize and protest against the universal discrimination they experienced at the hands of Israel’s ruling elite. Modeling themselves on the American Black Panthers, the Mizrahi social justice movement had its heyday in the ‘70s, with a few of Israel’s Black Panthers going into politics — Charlie Biton, for instance, served in the Knesset representing Hadash and the Black Panthers from 1977 to 1992. The Black Panther party merged into Hadash, and today progressives are organized under the Mizrahi Democratic Rainbow Coalition. One of its founding members, Moroccan Israeli poet, academic and documentarian Sami Shalom Chetrit, filmed the Black Panthers (in Israel) Speak, which came out in 2003.

Ashkenazi prejudice against Sephardic or “oriental” Jews resulted largely from the former’s uninformed views about the lives and communities of Jews from more than a dozen Arab countries, as well as their counterparts in Iran and Turkey. European Jews harbored an irrational prejudice against Arabs and thus considered Arabic- and Persian-speaking Jews to have arrived from hostile backwaters, viewing them as natives of enemy cultures — itself a preposterous notion, for there are no enemy cultures, no “us and them,” only strangers who have yet to meet and break bread. The fact that Jews from Muslim lands shared the same religious tradition was perhaps the only saving grace for the first generation brought to Israel by Zionist authorities, notwithstanding the fact that most Ashkenazim remained secular during Israel’s early years.

Today, many Sephardic or Arab Jews outside Israel are in solidarity with the American Ashkenazi and Israeli communities, which remain adamantly positioned against Palestinians and other Arabs, despite Israel’s peace treaties with Egypt, Jordan and more recently Morocco and a few Gulf countries. There is still some discomfort around use of the descriptive “Arab Jew,” and it remains less problematic to call oneself Sephardic, because it’s not a loaded term — the Spanish Expulsion happened a long time ago, and memory being what it is, Jews moved on, and kept that moniker without being troubled by it. Mizrahi or eastern/oriental came along much later, in the 20th century, in Israel, but otherwise, Jews from Iraq, Morocco, Yemen and other Muslim countries identify as Moroccan, Yemenite or Iraqi (as this video interview reveals). Most Arab Jews left their country very reluctantly, not knowing what awaited them in Israel—rather than the Promised Land and houses by the sea, what they got was dusty transit camps or cold barracks on the border or in the desert.

While Michale Boganim was discouraged from exploring contemporary Israeli bigotry against Arab Jews like her father Charlie, what she found in The Forgotten Ones is that discrimination in employment, education and even in the Israeli military continues to be a reality.