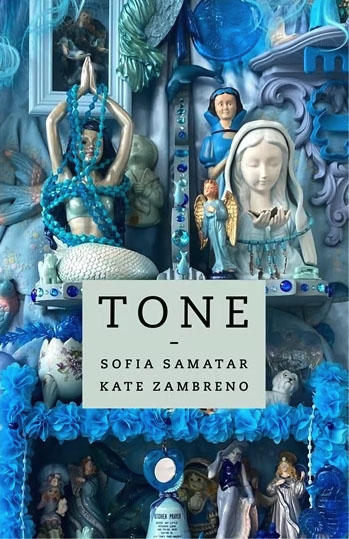

Literary criticism that includes Arabic translation, in Tone Sofia Samatar and Kate Zambreno indulge in a collective reading and writing practice with no intention of pursuing plot or character development. Instead, their primary objective is to capture the most elusive of literary attributes: tone.

Tone by Sofia Samatar and Kate Zambreno

Columbia University Press 2023

ISBN 978023121121

Safa Khatib

In the waiting room of an Urgent Care on Grand Boulevard in St. Louis, I plan to read, but don’t. I’m not ill, but a loved one is, and as she is seen, I sit in the row of chairs beside the window, just a few meters from the reception desk, my book closed in my bag. I watch a woman walk in and complain of chest pain at the desk. The standard scene ensues. One of the two receptionists takes her information, then after a few moments of pause, explains her insurance will not work, and would she “like to be directed to nearby places” where she might access care? The woman nods, but doesn’t wait for the advice. She turns to leave.

“Medicaid?” the other receptionist asks the one who had just turned the woman away. Her reply is short: “Yep.” The other’s voice then rises: “Ah…Bye!” Her harshness is satire, I think, shot through with both exhaustion and her knowledge of the cruelty of insurance-based healthcare. After a few moments, the receptionist who turned the woman away turns her chair to face the other and begins speaking slowly, somberly about her morning. “I woke just this morning with a heaviness in my chest I’d never felt. I’ve woken in panics before, but this was different. I scooped up Cooper and didn’t know what to do. I don’t have many people…”

The story continues. My listening ends.

—Safa Khatib

Tone, a collaborative study between Sofia Samatar and Kate Zambreno, is a rare kind of literary criticism that pushes the mind in many directions, from the 19th century, to the field of snow, to the white screen of the document, to the contemporary clinic. Literature in these pages is not a humanizing or edifying political force, nor do the authors follow the New Critics in evaluating literature only by its formal inclinations. “We would read a book about a boy and a city,” they write, “not for the character, the setting, or the plot that evolves between them but for the quality of the atmosphere, and if we returned to the book, it would be to breathe that air again.” With their attention to atmosphere, Zambreno and Samatar set literature firmly in the world as such, in which the distinctions between human and animal, labor and pleasure, feeling and form, action and thought are always interdependent. The category of “atmosphere,” equally at home in ecology and history as in literature, invites not the anxiety of analysis but the music of association and investigation. Reading about “melancholy and exhaustion” in a long riff on W.G. Sebald’s Rings of Saturn in the book’s first section, my mind drifts to Palestine, to the Human Rights report that Israel is using white phosphorus in the latest bombing campaign on Gaza.

Samatar and Zambreno identify their inquiry in the book’s opening pages: What is tone? What soon becomes clear, however, is that the book’s inquiry into tone is part of a more expansive consideration of the politics of reading. For Samatar and Zambreno, the most salient aspect of tone in literature is that it is never the result of an individual character, and so cannot be studied by an individual; tone is always collective, emerging only in relationships within the text, and so it must be studied as such, collectively, with others, in relationship. “How tired we were of the us that was us, how much we wanted to transcend this Name Name and that Name Name and all of what it meant, our names, our skin,” they write in the book’s introductory section. On one level, the tone of Tone is characterized by collective exhaustion — the familiar exhaustion, perhaps, that inflects intellectual and artistic work under late capitalism, both within and outside the university — punctuated by rapid turns of thought, memories of walks and conversation, epiphanies that sustain inquiry, pushing thought in new directions, like sudden breaths. Through the book’s seven chapters, the authors pursue the phenomena of tone through the work of many authors: Kanai Mieko, Bhanu Kapil, W.G. Sebald, Jorge Luis Borges, Neila Larsen, Renee Gladman, Sianne Ngai, and Hiroko Oyamada and Yoko Tawada. To their opening question the book will offer no single answer; rather, in shuttling through many possibilities that arise through various ways of looking at tone in various contexts, it offers the reader a guide for pursuing all phenomena that are, like tone, as obvious as they are difficult to grasp.

While Tone, to its credit, does not take any regional literature as its focus, its contribution will be especially welcome to American and European readers of translated literature from Africa and the Middle East. Because of the conditions of a global literary marketplace dominated by state-funding and multinational corporations, even the most well-intentioned venues for Arabic literature in translation must frame new work in geopolitical terms, using identity-based categories to attract interest from readers unfamiliar with the contexts from which the books arose. As Abdelfatteh Kilito, in the wry and mournful final sentence of his essay “Why Read the Classics?” writes: “Doesn’t the standing of Arabic literature rely upon foreign literature?” Kilito’s provocation is tongue-in-cheek, but it draws attention to the situation of writers of any background deemed “marginal” in the language of liberal politics. In a global literary marketplace funded by multinational corporations and government soft-policy, the danger faced by the writers of minor literatures is not so much condemnation or censorship (though this does occur more often than is assumed) as it is polite efforts to render the work accessible and exciting to uninformed readers at the expense of the nuances of its vision.

The LEILA project, for instance, an ambitious two-year initiative to raise the status of Arabic literature funded by the French Institute and EU “Creative Europe Programme,” employs a jury to curate a selection of Arabic books and authors for European publishers. In their list of books, The Fairy’s Heel by Lina Huyan El-Hassan is described as “A journey into Bedouin life and history in Northern Syria.” Clicking on the title reveals a more thorough summary and an enlarged image of the book’s cover beneath which a sample translation is available. Such historical and geographical context is deeply necessary, yet Samatar and Zambreno will push us to think more carefully both about the traps of historical thinking and the work of the well-meaning committees and juries behind the curation of international literature. To the jury of LEILA, the committee at the center of Tone — a “we” defined in the book’s dedication page as the Committee to Investigate Atmosphere — would issue a warning: to know what it means to breathe the air of the book is not so easy. The Committee would guide us to where history, memory and the present exist in uneasy relation, to the “shared affective atmosphere” of tone that organizes our experience of the text, that keeps us wanting to breathe the book’s air. It would caution us to ask: where exactly and under what circumstances can these books be read? Which books have not made it onto the list, and why?

Tone is far from alone in calling for collective inquiry into the experience of art and literature under late-capitalism. Given the spirit of their inquiry, the book should be read alongside the work of others. Their work sits along that of Fred Moten and Lauren Berlant, two scholars frequently cited in their pages. Yet readers will find echoes in other works as well, such as those of the anthropologist Stefania Pandolfo and philosopher Adriana Cavarero. Their commitment to a literary criticism rooted in an attention to ecological systems finds them in the company of the Zapatista Women, who in 2019 wrote a letter to women around the world in which they explained their inability to hold the Second International Encounter of Women in Struggle in Zapatista territory:

The new bad governments have said clearly that they are going to carry forward the megaprojects of the big capitalists, including their Mayan Train, their plan for the Tehuantepec Isthmus, and their massive commercial tree farms. They have also said that they’ll allow the mining companies to come in, as well as agribusiness. On top of that, their agrarian plan is wholly oriented toward destroying us as originary peoples by converting our lands into commodities and thus picking up what Carlos Salinas de Gortari started but couldn’t finish because we stopped him with our uprising.

So we are writing to tell you, compañera, sister, that we are not going to hold a women’s gathering here, but you should do so in your lands, according to your times and ways. And although we won’t attend, we will be thinking about you.

The collective of Tone might be imagined as such a gathering. It is a gathering that would also align itself with the Red Nation, who are (in their own words) a coalition working to combat the marginalization of Indigenous struggle from mainstream social justice organizing.

In a recent issue of Words Without Borders, Yasnaya Elena Aguilar Gil translates an essay by Mixe Communal Networks. Dated to 2172, “Art, Literature and Collective Earth Aesthetics” is a speculative essay that imagines a future in which creative systems are not beholden to capitalism and artists are no longer entranced by the structures it has produced. Writing from the future, the collective looks back to our time:

If we approach this period — which we would rather forget — with a curious and inquisitive mind, we will be able to discern, beyond the generalizations we are so accustomed to, that the Dark Night of Capitalism was not homogenous: during this period, there also were structures and currents that questioned and situated the art and literature of the time.

Tone accomplishes this questioning, and the book will be a vital resource for imagining the future of creative work in the 21st century. As Samatar and Zambreno write in the book’s final section, titled “Lighted Window, or Studies in Atmosphere:” “Light is a thing, we wrote once, but lighting is a relationship. There must be countless ways to light a room.”