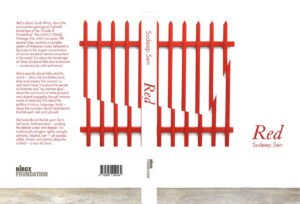

The Shadow that Doesn’t Leave the Shirt, poems by Maged Zaher

SplitLevel Texts 2022

ISBN 9780999570111

Youssef Rakha

For nearly two years now, getting together with Maged Zaher at one particular downtown Cairo cafe has been a semi-regular ritual.

It takes place in the outdoor seating area, during the day. Maged always arrives with plastic bags full of books, bought from the famous downtown stalls. On one of the two smartphones he carries, he usually also has some new poems secreted. Sometimes he reads them to me.

Once, inspired by something I said, he typed out a whole new micro poem as if he were texting while we sipped our drinks: espresso for me, a teapot for him, sparkling water for both of us. Poetry as a natural extension of friendship, just as it should be.

But poetry is far from our only subject. The conversation is always extempore and wide-ranging. It is so relaxed I sometimes wonder why it isn’t just pleasant. Because getting together with Maged is something else. It has the soul-stirring effect you might expect of therapy, but only if therapy were a two-way, cross-cultural confession, with bookish references and political commentary. What is it about our meetings that makes them that way?

The last time we met, Maged gave me the first of his seven books of poetry to appear since he relocated permanently from Seattle, The Shadow that Doesn’t Leave the Shirt (SplitLevel Texts, 2022). He said it was a qualitative leap in the trajectory of his writing. And, even though it overlaps with earlier work, and its contents have no direct relation with anything we‘ve talked about, the book feels like an aesthetic crystallization of the experience. It has the same soul-stirring effect, without the interpersonal immediacy but in a higher concentration.

Something about the way he can be so astonishingly explicit without ruining his art strikes me right away: “Sex and language/Two bad ways/To fathom our thrownness here/Some escaped those two paths though:/Monks and porn stars.”

But Maged‘s writing is already familiar. It shares a lot with the Arabic work of the group of poets known as the Nineties Generation, with whom both he and I are associated. It is written in the first person. It makes no distinction between the author and the speaker, or indeed the subject. And it combines a kind of emotional exhibitionism with intellectual wonder. Still, being in English and riddled with Western-inflected global references — Schiele, Cavafy, Arendt, Ovid — Maged‘s work is its own phenomenon.

On the first page, following a dedication, the poet explains that, together with his meds, these poems helped him through “a major mental illness” that first hit in 2019. In the work itself he describes a “sense of exclusion from the planet” that “comes after madness recedes.” He speaks of taking lithium, attending “strange gatherings” where people discuss “painful fantasies,” and waiting “for the medicine to undo the passage of time.” Towards the end of the book, he writes:

I look at these equations

That describe buildings’ behavior

Ah, I used to solve these equations in my twenties

Now I can’t I came to the US twenty-five years ago

Because I was good at solving such equations

Maybe it is time to go back

The book speaks more to those 25 years than their dramatic dénouement. It does mention an arrest, a mental hospital, sending “dick pictures to everybody.” But it doesn‘t dwell on any of that. Once he was well enough, it seems Maged came back to where he was born and raised. A wiz kid, he had started an engineering career without giving thought to his deeper needs. He arrived in the US only as a graduate student, and perhaps as a kind of refugee from the restrictive, oppressive society in which he grew up. “Escape from Cairo while living in it,” he writes, “is the craft of its inhabitants.” But now his stay in the land of sanity had run its course.

During his time in the United States, Maged became a software engineer, a scion of the corporate sector, “deep in the belly of the beast”: “You are Jonah/And you devour the beloved.” This clearly ate away at him. But he managed to hold onto a literary practice: “this awful business of poetry,” as he calls it, “Where I rearrange my masks/To peekaboo myself.”

In the afterlife, they will replace literature with mathematics.

As you read The Shadow you will sometimes notice the syntax breaking down, evidence of a mind straining “to be in two places at once.” Maged has continued to engage deeply with Arabic but he only writes in English — a language he did not learn properly until he was an adult.

He has also kept up his respect for the perfection and clarity of numbers, compared to the inadequacy and messiness of words. At the end of the book, he prays that on leaving his body his soul “becomes a mathematical object.” “In the afterlife,” he says, “they will replace literature with mathematics.”

This and writing in English while learning it made him a master of the one-liner. “Let us assume the innocence of dictionaries,” for example. Or: “When you pack your bags you lose some poems.” But it is not clear how much any of this influenced his approach to form.

Maged‘s pieces are almost always untitled, neither standalone poems nor sequences of a long poem. With rare exceptions, they live in the space between those two things. That way, he can explore his interests in depth without committing to anything too dogmatically solid.

More than in person — but that too — you can tell Maged has spent a huge amount of time, to quote Leonard Cohen, “meeting Christ and reading Marx.” A yearning for communist equity and Christian love form a kind of canopy for his thoughts and observations. But rather than denying or repudiating them, it actually spotlights desire and the body. Poetry as friendship turns into practical philosophy, kinda. Then you remember that poetry itself, however sane the poet, is often a form of madness.

I finished Maged‘s book in the course of one otherwise indolent day over the Eid break, but I haven‘t stopped returning to the poems in the midst of all kinds of busyness since. They‘ve certainly altered my view of a recently acquired true friend. But they have made me all the more eager to keep up the ritual.