System Ali live on stage in Jaffa in 2020 (photo courtesy Pasha Matz).

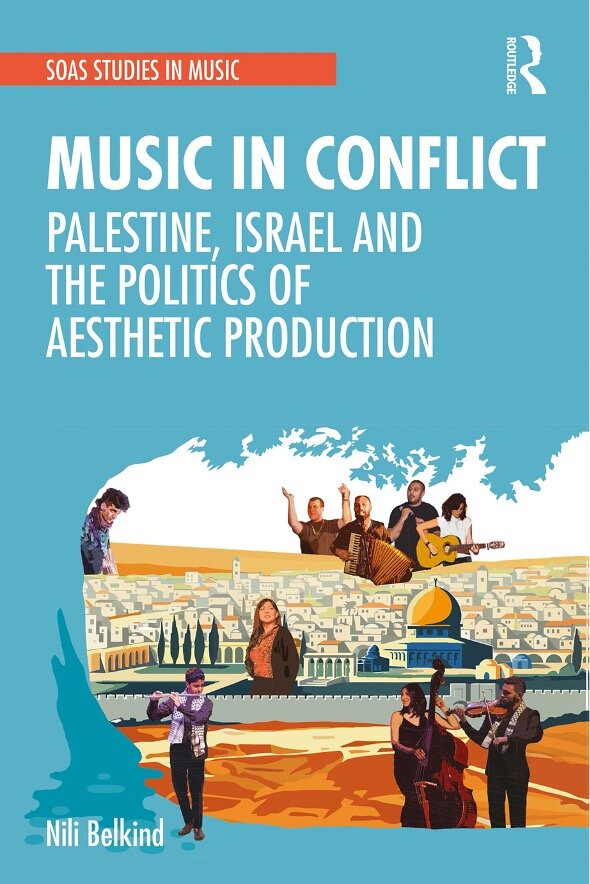

Music in Conflict: Palestine, Israel, and the Politics of Aesthetic Production

By Nili Belkind

Routledge (2021)

ISBN 9780367563172

Mark LeVine

Music in Conflict is available from Routledge.

In polarizing times — particularly when Israeli Jews roam the streets shouting “Death to Arabs,” and Hamas fires rockets on Israel as a form of protest against the expulsions threatening Palestinians in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan — one thirsts for non-binary alternatives, for narratives which remind us that often, the boundaries between us and them are not so clear-cut. Nili Belkind’s new book is one such narrative. Music in Conflict: Palestine, Israel and the Politics of Aesthetic Production starts out with the anecdote of a musician who sees the world as we might:

“I believe in a three-state solution: ‘Judea’ for the Jews, ‘Palestine’ for the Palestinians, and the rest of the country for all those who just want to live together.” This sentiment was expressed by Ben, a (Jewish) Israeli-American bass player and member of the Legacy Band, an R&B/hip hop ensemble shipped to the Middle East by the US State Department on a goodwill tour. The Legacy Band had just performed for an audience that included a small crowd of shy but appreciative Palestinian youth, and a sprinkling of representatives of East-Jerusalem’s American Consulate, in the auditorium of East-Jerusalem’s Notre Dame Church (December 4, 2011). Among the four members of the band, three of whom were African-American, Ben was the only one with native ties to the region. Ben was speaking with a Palestinian television crew that had come to cover the show.

Belkind explains that Ben’s alternative vision of a “three-state solution” amused the Palestinian TV crew as well as the American Embassy staff and just about everyone else within earshot. “By deterritorializing geographic boundaries and conceptions of sovereignty in favor of a ‘third state’ for those who ‘want to live together,’ it parodied contemporary debates that ubiquitously focus on the values of the one (bi-national) state or two-state ‘solutions’ to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict,” Belkind writes (20).

Another story is that of Ramzi Aburedwan, who figures prominently as a Palestinian who triumphed with music, after painful beginnings in a refugee camp. The composer, violinist and bouzouq player who founded the Al-Kamandjâti music conservatory, was photographed as a child throwing stones in the First Intifada. He later began playing music and benefitted from a musical scholarship in France. Later, when he returned to Palestine, he founded the Al Kamandjâti conservatory of music. Aburedwan became the subject of several documentaries and Sandy Tolan’s 2015 book, Children of the Stone: the Power of Music in a Hard Land.

Belkind devotes many pages to Palestinian Israelis, or the so-called ’48 Arabs, who are caught in a double bind, considered suspect by Israeli Jews and often rejected by Arabs outside Israel. Wisam Gibran, founder of the Arab-Jewish Youth Orchestra, explained to Belkind:

You come out of all this with a clear, sharp feeling that you are a stranger in all of this. Your real homeland is in exile… So you start to search for it, to create it, in the music, in musical language…In the end you understand that identity you don’t inherit, you make, you create. And if you say you create your identity then your identity comes from the future, because creation comes from the future, not from the past. For me Palestine, whatever it’s called, is something very individual. The Palestine I grew up on and demonstrated for, for me it doesn’t exist. Today I understand that there is Palestine of the Hamas, and Palestine of Abu Mazen, and there’s the Palestine of Juliano [Mer-Khamis] and the Palestine of Mahmoud Darwish. Every person has his own Palestine. And of course, Lieberman and Netanyahu have their own Palestines [too]. In the end it’s all utopian. (216)

Belkind covers a lot of ground in dozens of interviews with Palestinian Arab and Israeli Jewish musicians across the region, among them System Ali, the Palestinian-Jewish hip hop collective from Jaffa that raps in Hebrew, Arabic and Russian. System Ali put together “Can’t Breathe” following the death of Iyad El-Hallaq, an autistic man-child killed by border police in East Jerusalem last year, a killing that resonated with the kind of police brutality that led to the death of George Floyd last year as well.

Music in Conflict is an innovative ethnographic study of the fraught and complex cultural politics of music making in Israel-Palestine during the post-Oslo era, in which the author analyzes the politics of sound as they play out in the ongoing matrix of power under the military occupation in the West Bank and inside Israel or, as she explains it, military occupation vs. structural discrimination and the ways they blur into each other. She focuses on the ways in which music making and attached discourses reflect and constitute identities, shape public spheres, and contextualize political action. The book offers clear-eyed insights into the profound imbalances of power between the Israeli state, the stateless Palestinians of the Occupied Territories and 1948 Palestinians (citizens of Israel), all in the context of various levels of routinized violence.

Of special importance is Belkind’s focus on cultural policy as it manifests in the competing politics and discourses of resistance and of coexistence. She explores how music functions as a site of nation-building and resistance to the occupation among music institutions in the Occupied Territories, while in Israel, particularly in binational Palestinian-Jewish cities and towns, some institutions promote coexistence and shared models of citizenship through musical projects, showing how aesthetic models and performance contexts relate to larger political-discursive frames. The focus on resistance is further extended in a chapter about the different ways that music making is used to negotiate spatial and temporal boundaries — geographic, bureaucratic and somatic — imposed on Palestinians living under military occupation.

Read an interview with Nili Belkind on music and conflict in the Holy Land

Ethnomusicologist Nili Belkind received her PhD from Columbia and has published on a wide range of topics, including music and social movements, diasporic imaginations, cultural policy and diplomacy, borders, the urban space and ethno-national conflict. She spent many years working in the music industry as an album producer, record-label manager and A & R specializing in world music.

Belkind also explores the blurry boundaries of what she describes as “border zones” of expressive culture via the cultural politics of a binational city such as Jaffa, where fixed ethno-national divisions do not align with physical spaces nor individual identities, reminding us of the importance of providing comparative contexts to postcolonial studies and challenging the boundaries of teleological narratives that at times characterize scholarship on Israel and Palestine.

Why is this so important?

Because it opens up spaces for alternative imaginings of ethnic, civic, national and post-national identities, of resistance and coexistence (or co-resistance), and of the local and the global, that musically highlight the daily struggles of individuals and communities negotiating multiplex modalities of difference. Finally, her exploration of the lives and musics of Palestinians artists who are marginalized citizens (‘48s) highlights another kind of “border zone.” These artists perform multiple roles that may challenge or affirm, but always complicate, exclusivist nationalist paradigms and their associated artistic frames. By focusing in each chapter on different spatial, communal or personal geographies, Belkind weaves together a much larger puzzle of expressive culture in conflict, providing a textbook example of how sound studies, and music in particular, offer fresh sites for innovative and politically impactful research.

We see this right off the bat in the first two chapters. Chapter 1 focuses on Palestinian nation-making, resistance and conceptions of democracy as practiced at the Al-Kamandjâti conservatory and other cultural organizations in the West Bank. The reader is then implicitly invited to compare this to the dynamics of the musical politics of coexistence highlighted in Chapter 2 — as lived and practiced at the Jaffa Arab-Jewish Community Center’s choral projects. These projects invest and are invested in multicultural musical representations as a means of resolving tensions between Arabs and Jews in Israel, by showcasing and fostering more egalitarian models of citizenship. They occur against a backdrop of an exclusionary neo-Zionist trend that overwhelms the public sphere, as well as against Palestinian critiques of such projects.

Chapter 3 discusses the relationship between music, time and space in Occupied Palestine through exploring the role of music in the cultural remapping of the West Bank’s extremely confined spatial habitat, with case studies that include a concert that takes place at Qalandiya checkpoint; a tour that exemplifies what it takes to create and sustain cultural life in the shadow of the occupation’s colonial-styled bureaucracy; and finally, the ways in which the violence of the occupation and the discipline required for music making intersect in the mind and body of a single musician. Chapter 4 moves to Jaffa, a binational city that has sustained a colonization of long duration and that in the past few decades has been the neglected, Orientalized, yet fast-gentrifying-backyard of the municipality of Tel Aviv. The chapter focuses on how Jaffa engaged with the nationwide summer 2011 Israeli social protest movement — musically, sociopolitically and culturally — as voiced by the Jaffa-based hip hop collective System Ali.

Finally, the dissonances between spatial location, citizenship status and the political, ethical and musical alignments that such dissonances produce are discussed in the last chapter of the book, Chapter 5, which focuses on the lives and music of two Israeli Palestinian artists: Amal Murkus and Jowan Safadi. How these two amazing artists negotiate what Homi Bhabha has so presciently described as the “unhomeliness” of colonialism — which Belkind describes here as a sense of exile and strangerhood in one’s own home(land) — highlights the friction and frisson between art and identity for artists in a postcolonial minority situation. Another important contribution here is how she clarifies the nuances between these experiences inside Israel versus the Occupied Territories. While they are clearly part of the same larger system, they do function quite differently in many ways and Belkind shows why it’s important not to easily overlap them.