Climate change manifested in the melting of the oceans (Photo: Getty Images). <

<

Danielle Haque

Water is essential to life—it shapes and reshapes our landscapes. It contours our bodies and our worlds. It is also essential to our cultures: We use it to cleanse before prayer, to baptize, and to wash our dead. We imagine water as an eternal and renewable resource, yet pollution and overexploitation of our water resources mean that water is not tirelessly resilient. Centuries of militarism and colonialism create waves of ecological disaster that continue to break in the form of eminent domain, coastal erosion, fracking. In a world deeply wounded by colonialism and rotting with racism and ever-increasing economic inequality, art and poetry about water help us remember and embody the magnitude of water to life, mapping encounters between aesthetics, politics, and the landscape.

“I’ve contemplated whether there’s a crueler scenario,” writes poet Nathalie Handal, “not being able to see the sea but constantly dreaming it, or being able to see the sea but being forbidden to reach it?” Handal is not using the sea metaphorically: The sea is not a stand-in for home or a symbol for eternity. Handal means that Palestinians are prevented, through checkpoints, policing, and borders, from seeing and touching the sea. They are blocked from its resources and its pleasures. When Palestinians can access the sea, it is still regulated by the Israeli state. For those in the West Bank, the sea is accessible only via the acquisition of a pass and entrance through Israel. For Gazans, access is limited via regulations imposed upon them by the Israeli state – for example, while Israel recently expanded the distance fishermen from Gaza could travel into the ocean to 15 miles, it is frequently restricted to a much smaller distance.

More than just being blocked from the sea, in their daily lives Palestinians living under settler-colonialism face daily water insecurity. The World Bank reports that ninety percent of residents in the Gaza Strip do not have access to safe drinking water. According to the United Nations, sanitation and water conditions in the Gaza Strip are unsustainable. The UN further stresses that the Israeli state demolishes Palestinian rainwater collection cisterns and diverts water resources, including groundwater, from the occupied West Bank. Issues of water sovereignty extend beyond national borders: the many military interventions of the Israeli Defense Forces into Southern Lebanon, including its 18-year illegal occupation, were motivated in part for control of the Litani River. In 2006, Israeli bombs did substantial damage to Lebanese water infrastructure. In 2013, a World Bank report explained that, “A large majority of those living in Lebanon only have access to water for a few hours per day. The little water they do receive from public infrastructure is generally perceived to be of poor quality. Those who can afford it, resort to expensive bottled and tanker water.”

Exploiting resources and cutting off water access mark a distinctive logic and practice of occupation which fosters life for some and exposes others to harm and death. Some traumas are so severe, so primal and elemental and blunt, that they resist easy aesthetics: they trouble the symbolic.

Art about water is often metaphorical: signifying rebirth or freedom or thirst itself. Nathalie Handal’s writing, however, like so many others writing about Palestine, often resists the simple metaphor and instead directly reflects the realities of domination through water occupation and access to diminishing resources. For her and others, water is not a only symbol for life, but also embodies brutal exposure to suffering and death.

Graphic courtesy of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. <

<

Through all the various ways art is marketed and reviewed in the United States, Arab American literature is excluded from discussions of environmental writing, with writers like Handal being read narrowly in terms of race, religion, conflict, and migration. Geopolitics, conflict, and repressive regimes can overshadow the environmental disasters they cause, making the biosphere into an ancillary concern. Disconnecting land and water from these issues dismisses Arab American artists from discussions on climate change. Conversely, we too often use “environmental” to ignore the human workings in the devastation of people and places. Human actors set the stage for who suffers the most from environmental disasters—and human actions.

In literature, the climate crisis and its attendant diminishing of natural resources is often addressed through appeals to the impending survival of our children, dwelling on dystopian futures and images of humanity’s catastrophic demise. In The Great Derangement, the novelist Amitav Ghosh asks why climate change presents such a challenge to serious literary fiction: He believes that the climate crisis is also a crisis of imagination. In his book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, literary and environmental scholar Rob Nixon describes this same narrative challenge in terms of “slow violence.” Unlike spectacularly violent events, these are the kinds of creeping, slow-moving calamities that almost resist description: exposures to toxins and rising sea levels, long-term drought and the incremental extinction of local flora and fauna. Unlike bold images of something as catastrophic as the August 2020 Beirut port explosion that incites strong reactions, there is a challenge in capturing the traumas of water pollution, demolition waste, and hazardous chemicals. Some writers have attempted to capture such devastations, helping readers empathize with the slow-moving environmental violence of settler colonialism and racism.

Haque’s Interrogating Secularism frames its argument around the literary work of such writers as Khaled Mattawa, Toni Morrison, Laila Lalami and Mohja Kahf.

<

<

Palestinian American poet, Rasha Abdulhadi (they/them) does so by inhabiting our moment instead of mourning our future. Their book of poetry, Shell Houses, is rich with natural imagery, peppered with deer, insects, sheep. Abdulhadi juxtaposes poetry about the Nakba with poems such as “Monsoon on Dinè,” about the changing climate and Navajo land. By doing so, they finds narratives of connection between Israeli occupation in Palestine and occupation of Native lands in the United States. They warn us, “we beat and bruise and break what sustains us daily.” In their poem, “is Palestine,” Abdulhadi uses Palestine as a metonym for harm. Palestine, they tell us, is in every “drop of water from the Diné nation used to pump/ the coal slush that lights up Las Vegas” and in every “arrest of a Black man, woman, or child in Atlanta.” In the poem, Palestine correlates with racism and Native disenfranchisement elsewhere. In political spheres climate change is often presented as a crisis fiction, a made-up conspiracy meant to corral us, paralleling the unbelievable status of Palestine and Native land, as places and events rendered invisible in history and on maps. Because poetry offers up relational and imaginative possibilities, readers can understand the poem’s multiple landscapes as linked through the violence done to the people living upon them, but also as connected through water’s planetary cycle, joining us through the atmosphere and underground.

Australian philosopher Glenn Albrecht coined the term “solastalgia” to describe “the pain experienced when there is recognition that the place where one resides and that one loves is under immediate assault (physical desolation). It is manifest in an attack on one’s sense of place, in the erosion of the sense of belonging (identity) to a particular place and a feeling of distress (psychological desolation) about its transformation.” Solastalgia is the lingering sorrow of Abdulhadi’s work. It is place being swept out from under one’s feet, being displaced in the place you are. It is the ocean that can be seen and not touched. It is a mourning for the present.

Solastalgia can take another form: regulating the earth to a luxurious worry of the West, a longing that cannot be articulated elsewhere. “She dreams of shouting from/ a high place, her voice cascading down/ wild rivers,” Lisa Suhair Majaj writes of a woman who wants the freedom to love place but is denied. “Do Arab women do things like that?” the audience asks. “We have so many problems!/ – our identity to defend, our cultures under siege./ We can’t waste time admiring trees!” These writers challenge assumptions about who gets to enjoy the forest, who can worry about environmental disaster, who can dive into the sea. In this way, writing about invasion and occupation is writing about climate change. Writing about surveillance and racism is writing about climate change.

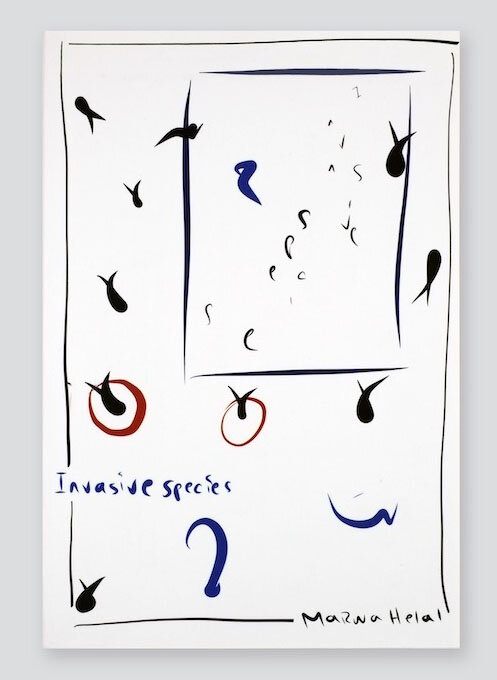

In the middle of her book of poetry, Invasive Species, Egyptian poet Marwa Helal inserts a scan of an article from the Ludington Daily News describing the US Department of Natural Resources adding to the list of invasive aquatic species. Helal’s poems are collectively about her experiences of immigration and surveillance by US bureaucracies. Invasive species works as a metaphor for how the US imagines its immigrants as threatening and predatory, a nuisance impossible to eradicate. Nestled under the article is another piece about volunteers applying to be hosts at Michigan’s state campgrounds. The contrast between offering hospitality on shared land (albeit stolen land) and monitoring non-native species is stark. A few pages later, Helal entreats us to zoom in and zoom out and includes another article, from Ecology, about native fish diversity mitigating the effects of invasive fish species: Native richness helps the invader more easily incorporate into the aquatic environment.

In her book Invasive Species poet Marwa Helel uses water as a metaphoric vehicle for speaking about borders.

<

<

That Helal’s illustrations are fish is telling. Aquatic species often arrive via the ballast water of oceangoing ships, concomitant with the movement of people. Invasive species can be accidentally smuggled content, plants that attach to boats and ideas to people. Because oceans and rivers are connected by deltas and watersheds, there are no barriers to movement. While borders on land can be reinforced, there is hubris in thinking we can draw lines on the sea. She later refers to herself as an invasive specius sapien of “no nation a fish an ocean pulsing between its jaws and caught.” Though she uses water as a metaphoric vehicle for speaking about borders, the poem’s title itself is literal: “Invansius specius sapien reflects on the consequences of synthetic apertures.” It refers to a radar system used by scientists to map ocean environments and by the military to surveil and target, tracking oil spills and pinpointing weapon delivery. In the same way Abdulhadi uses water both as metaphor and literally, Helal does the same here: the actual surveillance of the aquatic landscape for military use metaphorized into a commentary on people as borderless sea creatures, alien lifeforms trying to survive in an alien ecosystem.

There is a danger in collapsing struggles into a monolith. It is not enough to say we are separate and similar, but rather, these writers say: We are deeply intertwined. The historical contexts are different and there are power differentials even between various struggles, but shared experiences of settler colonialism, environmental racism, and slow violence link movements for sovereignty. Lines on maps cut across ecosystems without regard for life; border walls disrupt animal migration and ecosystems as well as creating avenues for migrant deaths. These phenomena are all related: a cartography of patrolling life itself.

All of the these writers engage with water in its various shapes and its various functions, mapping themselves onto bodies of water, mapping the water coursing through bodies.

As Handal’s poem’s Lettera Lirica, Jerusalem illustrates:

Because I see the shape

of your shadow in every city

Because you are on the edge

of every body of water

Because your language is tilted

towards the world

but you’ve kept some sentences

well-hidden

Because some words together

can frighten loneliness

like the lagoon moving aside

for the sea—Nathalie Handal

For these artists, words and water—memory and history—mirror each other as psychosocial isomorphs.

<