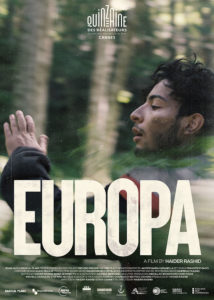

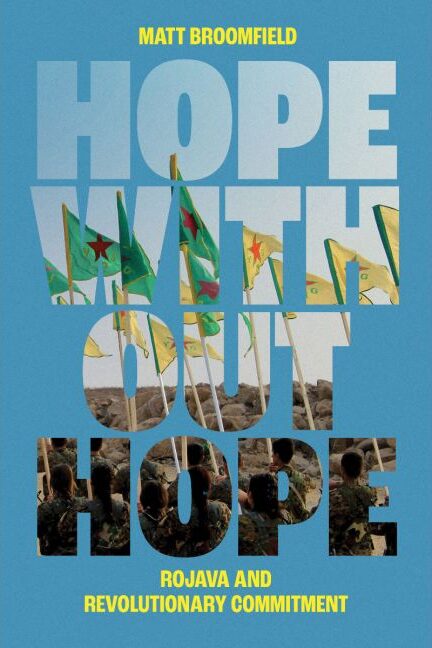

Journalist Matt Broomfield takes a look at the history of the Rojava revolution in Syrian Kurdistan as both an heir and a blueprint for the emergence of global liberation moments. The central question of his book, which goes naturally unanswered, is what is there left to do when everything else has already failed? Isn’t hope a grand delusion?

Hope Without Hope: Rojava and Revolutionary Commitment by Matt Broomfield

AK Press 2025

ISBN 9781849355667

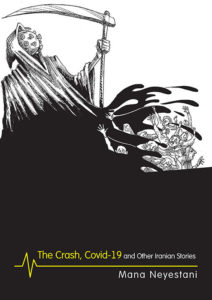

Hol Camp is a refugee camp on the outskirts of the town of Al-Hawl, in eastern al-Hasakah governorate in northeastern Syria. Now under the control of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), also known as the Kurdish-led Rojava region, the camp illustrates the paradoxes of imprisoning the thousands of captured Syrian and Iraqi Daesh fighters, as well as foreign ones, in prisons and camps guarded by the Syrian Democratic Forces in AANES. Here, fighters who fought for Islamic State are held more or less permanently, along with the women and children affiliated with Daesh imprisoned at Hol Camp.

The camp has been described as a ticking time bomb where IS can regroup and rebuild. On the one hand it is formally recognized as a refugee camp by the UN, and still enjoys extensive support by international NGOs. On the other, the autonomous region hasn’t received any kind of diplomatic or political recognition, even as a legitimate political actor within Syria. As a consequence of this paralegality, aid can be delivered to Hol Camp easier than to other refugee camps within AANES, including those sheltering the displaced victims of Daesh. This translates into a perverse situation, where the locals who survived the genocidal violence of Daesh are now hired to tend to their needs. Not to mention the constant risk of escape created by regular Turkish air strikes on the region.

This is one story among many recounted in Matt Broomfield’s book Hope Without Hope: Rojava and Revolutionary Commitment, drawing on his experience of three years working as a journalist in Syrian Kurdistan. The absurd circumstances of Hol Camp are significant in Broomfield’s narrative, not necessarily only because they expose the internal contradictions of international aid, the geopolitical calculations of the great powers, or the uncertainty of Syria as a whole in the post-Assad era. The book is not a history of the Rojava conflict and revolution, but a rich cultural and speculative narrative about what kind of future political imaginaries are possible today, against the background of the tremendously complex, volatile, violent, and still incomplete history of Northeastern Syria.

There’s probably no better place to look. It’s not just civil wars, oil rentier states, fragile borders, transnational terror, occupations, drone warfare, and the dismantling of international law. Amidst this chaos, there’s a political project, perhaps unlike any other in the world today. A secular polity with the ambition of direct democracy, based on confederalism within a decidedly multiethnic enclave, has become home not only to a variety of faiths but also of degrees of religiosity. Also in the mix is a loose idea of socialism, consistent but not identical with the global left. Broomfield adopts a hyperbolic view of the Rojava revolution, and finds in it the seed for future governance in the region. He also uses it as a blueprint to interrogate the failures of other left movements worldwide in formulating a coherent project of politics.

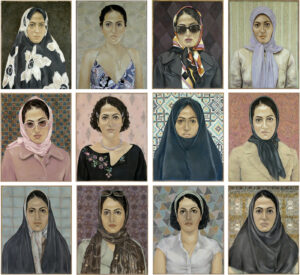

Taking the longer view, the author traces back the emergence of AANES far beyond the Syrian civil war. Bloomberg considers the decades-long Kurdish struggle in the region, from the different global and regional powers that suppressed Kurdish autonomy, to the protracted conflict between the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and Turkey, and their historical exclusion in the Syrian Arab Republic. In this excursus, there’s also a hard look at orientalizing images of Kurdish women fighters in western media; the betrayal of the international coalition for a crucial partner in the fight against Daesh; as well as the morally ambiguous compromises of AANES through the years of war in Syria; and the internal political maneuvers and social conflicts that make the unrecognized autonomous enclave a fragmentary success.

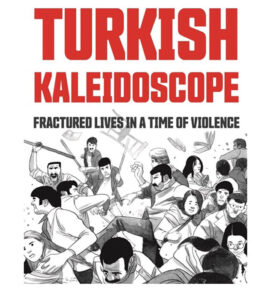

Broomfield juxtaposes this narrative with the permanent sense of defeat in the global left and a series of protest movements, from South America to the Middle East and East Asia, from Occupy Wall Street to Turkey’s Gezi Park to Tahrir Square. He argues that Rojava might be the most successful contemporary heir not only of the Arab Spring, but all those other movements that often quote or reference each other. Ultimately, he correctly points out the sense of historical melancholy over the fate of Marxism in the 20th century that sits at the heart of the leftist political imagination. It has prevented the formation of an alternative to the predicament of our current capitalist realism, and to the state-centered liberal democracy that has entrenched brutal inequalities, fueled wars, and turned a blind eye to mass displacement.

Broomfield also well understands that the experiment of Rojava can only exist and perhaps thrive — albeit not always — within the very specific conditions of Northeastern Syria, and that it simply cannot be exported anywhere. He does not propose any governance theories or resistance strategies. Instead, he explores the success, sometimes through abject failure, of the Rojava revolution, and through the lens of the concept of hope — a hope often fragile and fleeting and which has animated the Kurdish struggle for generations. This hopeless hope, in the face of genocidal campaigns and broad political exclusion, is anchored in the belief that this lack of hope, of political recognition, of long-term stability, has enabled a project so ambitious, yet so endangered and uncertain, to survive against all odds. It is almost as if Broomfield is using “hope” here in the way that millions of Palestinians use “sumūd,” to represent steadfastness in the face of decades of oppression.

As an observer, the author is aware that the territorial, strategic, and political gains are relatively limited in a situation that is still shape shifting and that there are no future guarantees. In this fleeting moment, a revolutionary condition becomes not only possible but absolutely necessary. Even in the case of eventual failure, the history of the Rojava struggle will become part of the consciousness of global revolutions. The central question of the book, which goes naturally unanswered, is what is there left to do when everything else has already failed? Isn’t hope a grand delusion?

In these times of war and genocide, the hope industry alienates us from feeling the depth of our current despair.

Broomfield draws on a wide spectrum of 20th century authors, especially in the Marxist tradition, who have grappled with this question, and rescues for contemporary readers utopian elements of political thought, long buried by decades of disaster and disenfranchisement.

At this point the book’s trajectory becomes both obscure and interesting, featuring concepts from European philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben’s bare life, Theodor Adorno’s negative utopia, or Ernst Bloch’s principle of hope. Although useful in his speculations about the future of politics, Western thought takes over Broomfield’s first-person narrative in a manner so strong that it overshadows the subjects of his book. This approach makes his streams of thought inaccessible to readers not thoroughly trained in the same European tradition that often acquiesces to liberal democracy and imperialism. The faith of the author in the project of socialism, while critical, suffers from anachronism at times, and avoids discussing in depth the tragic fate of socialism or authoritarian elements in Marx’s thought beyond hope and utopia.

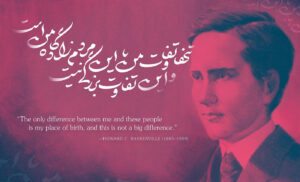

Yet hope, as the author knows well, is multifaceted and capricious. Accordingly, there are two moments of spectacular clarity, almost diametrically opposed, where the power of the book becomes manifest. The writings of Abdullah Öcalan, the Kurdish leader and political theorist, imprisoned in Turkey since 1999, appear throughout with detailed insights — a rare occurrence in books, on his ideological shift from Marxism-Leninism to democracy, confederalism, women’s liberation, and environmentalism. This transition is important, given the influence of Öcalan’s thought within AANES. His departure from the purely positivist and materialist worldview of orthodox Marxism opened up the possibility to re-imagine the Kurdish revolution in terms of active hope and transnational struggles.

At the same time, Broomfield passes a scathing criticism of the passive hope industry; namely, the proliferation of self-help, self-care, astrology and therapy products and services that permeate contemporary culture with neoliberal market consensus. He argues that it divorces hope from specific material conditions, creating a kind of determinism in which human fates are sealed and cannot be changed, but only minimally transformed by the individual. There is no collective agency or responsibility. The hope industry also invades the space of politics, for example in the slogans of the Obama administration that translated into reckless air bombardment in the Middle East, and the NGO-ification of solidarity that bureaucratizes and sanitizes community work. In these times of war and genocide, the hope industry alienates us from feeling the depth of our current despair.

These insights are essential in telling the story of Rojava because thinking outside the paradigm of nation states implies not simply the reform of existing institutions. It is a radical transformation of everyday life as we know it. The facts on the ground in AANES suggest that the project is impossible, with only partial results, but perhaps it is for this reason that it shouldn’t be abandoned. How to articulate a practical hope for this transformation, however, is an urgent but difficult task. Broomfield walks the whole nine yards, thinking through Western philosophical and historical traditions, about millennialism, Messianism, and the apocalypse, from Late Antique to medieval sources, German Idealism, the Holocaust, modern thought and the Arab Spring, to locate an impetus for this transformation of everyday life in anti-colonial, anti-capitalist terms.

Broomfield suggests that messianic movements of the past, with their emphasis on salvation, have inspired decolonization struggles around the world. He cites examples not only from organized religion, but also from modern political movements. I can no longer be sure, however, that the chair of the Messiah should be occupied in our time and age, perhaps because anyone who occupies the chair of the Messiah is potentially a pretender. The author doesn’t have a problem with the Messiah being a pretender, as long as he gets the job done — recalling unflattering portrayals of Öcalan as a charlatan at worst, and an unsystematic thinker at best. It is the author’s contention that the most truly revolutionary moments emerge not from utopia alone, but from a process of negotiation between ideals, material conditions, and political compromises. Perhaps this is the most valuable insight in the book. Yet in these moments of extreme violence in the region, and the threat of environmental collapse, as well as economic precarity everywhere, hope is an enormous task, best not left to unreason.

There is a telling passage in Hope without Hope that illustrates the urgency of Broomfield’s argument:

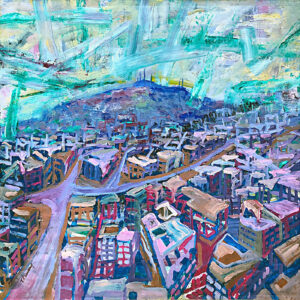

Driving through Rojava means driving alongside the Syrian-Turkish border, where it’s impossible to escape this fundamentally colonial sense of struggle at the mercy of an omnipotent, transcendent power. The border is demarcated by the world’s third-longest wall, stretching over 750 kilometers. Newly constructed after the declaration of Kurdish-led autonomy, it divides cousin from cousin, wheat field from wheat field, (Syrian-occupied) Kurdistan from (Turkish-occupied) Kurdistan. The wall is militarized with EU money; patrolled by armored cars; monitored by unblinking watchtowers; and equipped with remote-controlled weapons; light, movement and acoustic sensors; jammers, radar, and laser-based detection technologies.

This is much more than dystopia or the apocalypse. It is the total unmaking of a rational system that preached order and the primacy of the technological imagination over history or any past beliefs and utopias. However, history has come home to roost after centuries of plunder, conquest, and annihilation, and the experiment of Rojava in self-governance, solidarity, free association, and hope — regardless of how imperfect — remains as relevant as ever. Countless refugees continue to roam the earth, from Colombia to Gaza, Syria to Afghanistan, Myanmar to Sudan, and seek shelter from the unsafety of dangerous skies. At the same time, both western jurisprudence and technology are deployed in the service of preventing their safe arrival. Perhaps the solution to this enormous suffering can no longer be found in states or liberal democracies. Nobody it seems knows the answer.