Israel and its US and European supporters are engaged in a desperate propaganda attempt to paint the destruction of Gaza as self-defense and a justified response to the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, while much of the rest of the world (including students on college campuses) calls the onslaught for what it is — genocide. But the ethnic cleansing of Gaza is part of a national program that began in 1948.

As if Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza were not enough, I have decided to venture into other genocides. Harry Harootunian’s memoir, The Unspoken as Heritage, interrogates his parents’ silence about the Armenian genocide (1915-1917), how they escaped death, their families and friends who did not, and their loss of home and country. He grew up in a family with no family, bereft of history. His parents did not speak of their childhood friends, games, mischief, delights, and chagrins, even before the Ottoman Turks commenced their genocide. And so the Harootunian children grew up in Highland Park, Detroit, ignorant of even the basic make-up of their families — missing the names of aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents, their worlds, village life, social gatherings, and rituals. The book is a reflection on the wide-ranging power of silence and its transmission — how trauma and the utter loss of home, family, and the everyday markers of memory are inherited and sustained as a presence so potent as to never recede. Harootunian essentially writes about an absence. In so doing, he calls up worlds, through traces, oral history, and desire, and in the process, readers learn quite a lot about the markings and meanings of genocide.

For as long as I can remember, like most Palestinians, I noted social expectations to keep silent about Palestine — that is, in polite society in Western countries where I lived or visited, but also in certain circles in Lebanon and in the Arab countries that signed normalization agreements with Israel. I have always said I am Palestinian and American, which is often quite enough to disturb these expectations. Depending on the persons in front of me, I might see a cloud passing in front of their eyes, or at least an internal stand to attention. What a jarring subject, this brutality of Israeli settler-colonialism and apartheid, the magnitude and heartbreak of Palestinian suffering and loss!

All my life I noted too, in parallel, the undiscerning ease with which colleagues, professors, acquaintances, and friends, mostly in outer social circles, converse about visits to Israel for work or play. “Did you go into the West Bank?” I would often ask. Taken aback or mealy-mouthed, they would provide the same refrain: “It was not possible,” or “I once visited Bethlehem.” Palestinians living in exile also habitually hear Israeli Jews gaily exchange stories about where they did army service — so elemental is it to their identities that it is often the first question they ask one another when they meet. Were I to ask, on occasion, “What did you do during your military service? Search and interrogate Palestinians? Block them behind walls, in cage-like structures, like cattle? Humiliate them? Arrest, torture, jail, or execute them? How many crops and trees did you destroy, help enclose, to confiscate Palestinian lands?” it would be like shattering glass — then and there.

Until its genocide of Palestinians today, Israel has enjoyed a vast arena within which the movement of Israeli people and products, rhetoric, and sentiments, is largely unhindered by any recognition that the state’s existence, from the very beginning, has been dependent on mass theft, killings, imprisonment, and the steady, harrowing destruction of Palestinian society and presence.

When hearing these soldierly exchanges between Israelis as we Palestinians walk down the street, hold drinks or food at a social gathering, enter stores, or ride the metro, we are taken by surprise, even for a few moments, by whiplash memories of Israeli occupation, directly experienced or inherited. The most insignificant remarks we remember durably, implicitly silenced as we are, like when my dissertation advisor handed a manuscript to an assistant, instructing her to send it to Israel, before casually turning his attention back to our discussion, oblivious to how this must affect me. When people mention their friends’ trips to Israel with insouciance, as if Israel is a normal place to visit or to live, it is the mark of power and privilege that they need not think of our disquiet. Until its genocide of Palestinians today, Israel has enjoyed a vast arena within which the movement of Israeli people and products, rhetoric, and sentiments, is largely unhindered by any recognition that the state’s existence, from the very beginning, has been dependent on mass theft, killings, imprisonment, and the steady, harrowing destruction of Palestinian society and presence. The purpose of genocide is, we must not forget, mass theft and increased wealth.

The silence imposed by polite society, which normalizes and covers up Israel’s crimes, is a thick haze. In her essay “Silence” (in Les Petits Virtues, 1962), Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg writes that “silence must be considered, and judged, from a moral standpoint,” concluding that it is “a fatal malady.” If Palestinians protest facile talk about Israel, we may be treated as social pariahs. But most often we find ourselves muzzled. Later we weigh up all the things we should have said, had we space and the presence of mind. And these unsaid words remain caught in our throats for days. Following the psychoanalytic premise, when people are not ready to hear, they will not. And we sense that most of what we’d say would fall on deaf ears. The problem with our interlocutors is not ignorance, but indifference, and very often opportunism, an unwillingness of many people to rub against conventional ideas about Israel, lest their words cost them opportunities and useful connections. Yet virtual life, social media, and alternative news sources are accessible to all who are concerned. As a result, I no longer believe in such ignorance. I became fully aware, when I lived and worked in New York after 9/11, that most Americans had a vague awareness, even if they could not place Iraq on a map, that they somehow benefit from the American-Israeli subjugation of all of West Asia.

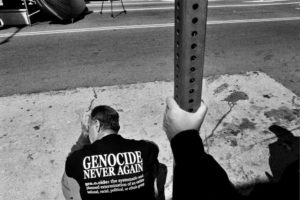

With today’s massive global movement against the Israeli genocide and in support of Palestinian rights, heterogeneous and young, with a growing number of Jewish participants in its ranks, there is more space to speak out and be heard. But the repression of these movements is ongoing and persistent, with even minor activists harassed and arrested and fired from their jobs in the US, and in much of Western Europe (especially Germany — still protecting genocide, it seems). And now police forces are called onto campuses to remove peaceful encampments and brutally arrest pro-Palestinian protesters, students and professors both. We must not say “too much,” it seems. But certain well-known Jewish anti-Zionists have clout: Ilan Pappé, Israeli historian at the University of Exeter (exiled from Haifa University years ago), reminds the world that the people of Gaza are refugees from destroyed Palestinian villages upon which lie the Israeli settlements and kibbutzim that border and control the Gaza Strip. And these were the very targets of the Hamas fighters. Berkeley scholar and theorist Judith Butler insists that, to be historically accurate, we should call them resistance fighters. And Haaretz journalist Gideon Levy defines Israel as a violent settler-colonial, apartheid state, and says that nearly all Israelis consider themselves to be the unique and only victims, and points out that they support the genocide. Like ventriloquists, we repost their statements on social media.

In Marseille, where I live, beyond my intimate friends, I am surrounded by silence. I think about this all the time, how it can be that the Israelis continue, on and on, to slaughter and demolish, to carry on with their happy pogroms and accelerated land-grabbing all over the West Bank, Jerusalem, and the boundaries of Gaza, humiliating everyone and perpetrating atrocities, including executions and the rape of detained Palestinians, and yet most people around me remain silent. One recent exception was an Irish artist who swooped in on me at a gathering, her expression brimming with concern. She held me long and tight, to the point of crushing the wind out of me. I welcomed her crush, as it made me realize that I had been missing it for months. I first met her as a friend’s friend, and we rarely cross paths. Her act was one of solidarity.

Like most Palestinians and people in solidarity with them, I am haunted by Israel’s genocide, its pogroms in the West Bank and escalation of land theft, the killing fields, the barbarism and utter destruction of Gaza and its ancient civilization and all historical landmarks the Zionists deem not their own. Participating in this barbarism are all the powers of the world that are collaborating with and abetting Israel’s crimes, particularly the United States, which, tellingly, shares with Israel a colonial-settler project. Ibn Battuta, the traveler, ethnographer, and historian from Tangiers, wrote in 1326: “From there we went on to the town of Ghazzah, which is the first of the towns of Syria on the borders of Egypt, a place of spacious dimensions and large population, with fine Bazaars. It contains numerous mosques, and there is no wall round it.”

Zionist Israel will be recorded as one of the military powers in history that razes civilization to the ground. And it is exactly the decades-long, unconditional financial and military support that Western powers grant Israel, repressing critical views and protests, that enables the Israelis to freely commit genocide and other atrocities in Palestine. Absolute power in any country quickly transforms into a “pathology of power,” as the late Eqbal Ahmad, Pakistani writer, academic, and anti-war activist, termed it.

A friend in Jenin describes to me how the Israeli army enters the city, from several directions, on an almost daily basis, now from Haifa Street, now from the road to Nablus. The army is accompanied by battalions of bulldozers that dig up all the roads, time and again, which the municipality then attempts to patch up, as well as the infrastructure for water and electricity. Drinking water mixes with sewage. A jeep passed by a friend’s colleague’s home and soldiers stepped out and executed his son and a friend, ages eight and 15, who were playing soccer together. Soldiers randomly enter homes and destroy the interiors, like that of the newly married daughter of another friend, and urinate on the mattresses. And we have all seen (or should see) Israeli soldiers’ videos taken in Palestinian homes in the West Bank and Gaza, showing whole families blindfolded and forced to their knees, while the soldiers taunt them, eat their food, or stand on the beds, laughing, saying they should have sex in front of the family.

How can it be that the Israelis flaunt their atrocities, and continue to document their mad and obscene behavior? And how can we understand the soldiers’ apparent joy in genocide? Harootunian writes about the sadistic pleasure of the Turkish soldiers carrying out their crimes against the Armenians, cruelly slaughtering a defenseless people, and finally forcing them on a death march through the desert. The Germans learned from the Turks that genocide meets with complicity or indifference, as Harootunian points out, adding that in fact many of the Turkish architects of the final solution for the Armenians fled to Germany. Genocides connect in chains.

We know that the prerequisite of genocide is the dehumanization of an entire people. In the case of the Israelis, they have long dehumanized and violated the Palestinians with exceptional impunity — to the point of being able to slaughter them not like livestock, but worse. In one video Israeli soldiers posted of themselves, they turn the pages of a wedding album and make fun of the couple in the pictures; in another, a soldier pulls a piece of lingerie over his military fatigues and prances around in a home in Gaza; another video shows soldiers announcing they will kill all of Gaza’s teachers* and students and pointing to a school in the background just before they blow it up. It is significant that they imagine Palestinians in their everyday lives, and in human categories parallel to their own: getting married, for example, or going to school. At the same time, they efface these same Palestinians whose intimate lives they interrupt, driving them out of their homes or executing them. Recent videos by Palestinians show Israeli drones over Gaza that play recordings of babies crying in order to lure people out of shelter, at which point they kill them. This genre of social media posts serves to document Israel’s open hunting season against the Palestinians. But these posts, hundreds of them, also constitute a record of the intimate workings of fascism. As such, the soldiers’ videos are in some ways more horrifying than the media footage of buildings collapsing on entire families in Gaza.

We must note the dehumanized state of the Israeli soldiers themselves, who take pleasure in their cruelty, as well as most of the population of Israel, which adheres to the genocidal-suicidal logic of “us or them.” If the Israelis in particular decide against searching the internet to see what is actually happening in Gaza and the rest of Palestine, and only watch Israeli media droning on about the Israeli hostages, it is because they already know what they will find. It is not a simple case of ignorance enabled by mendacious, controlling media.

The Western powers’ creation of and subsequent collaboration with the Zionist project is of course historically documented. The Israelis have sequestered Palestinians in the concentration camp that is Gaza for nearly twenty years now, and systematically violated Palestinian human rights in all of Palestine, continually confiscating their lands and water. These wide-scale practices, and their antecedents in earlier decades, have long been met with indifference by nearly all Israelis, who frolic on the beaches and outdoor cafes of Tel Aviv, not far from Gaza, as well as of the world powers, which support Israel and peddle Israeli propaganda. Most Israelis are either active soldiers or reservists (who yearly assume active duty, up to a certain age) or, if older, are former soldiers. Most have direct experience as occupying forces. The brutal practices of this settler-colonial state take place not in a faraway colony; indeed, the daily lives of all Israelis are structured by military repression and an apartheid system. It has long been a perversely intimate occupation.

Subjugating another people living in the same space depends on ideological groundings. Jewish identity, both religious and secular, is powerfully formed by the biblical idea of the Chosen People, which coexists with the persecution of the Jewish people, from the Pharaoh of the Old Testament to Nazi Germany. But it is Zionism that later developed an ideology of exceptionalism and ethnic supremacy. And Israel, which boasts one of the most powerful militaries in the world, declares the Palestinians an “existential threat,” even when they live under military occupation in a blockaded territory, are imprisoned on a massive scale, and have their labor exploited (as detailed by New York writer and academic Andrew Ross in his book The Stone Men: The Palestinians Who Built Israel).

The Israelis have long controlled every aspect of Palestinians’ lives, from the river to the sea, denying them equal rights, holding them in perpetual siege, packing them into smaller and smaller ghettos, behind ever-extending walls, and in concentration camps. In so doing, Israelis replicate social and legal conditions similar to what the Jewish peoples themselves suffered, creating versions of historic ghettos. Within the land of 1948, Palestinians live in divided towns and cities as an unwelcome, unequal minority. And the Israelis, by their twisted system, simultaneously confine themselves behind walls.

Separation is always dangerous. Mixed neighborhoods and schools, on the other hand, encourage cross-community friendships and romance, and reduce socio-economic divides as well as the dehumanization of the underclass and minorities. With few exceptions, such pluralist social arrangements can be realized only after the end of Zionism.

When I took my children in 2015 to visit our homeland, we spent our sojourn with family and friends in Jaffa, Jerusalem, Ramallah, and Jenin. When in Jerusalem, I was disoriented by the urban apartheid system, which included a new, sleek road built for Israeli traffic only, one that divides the city at Lion’s Gate like a long gash. I asked a couple of soldiers for directions to the cinematheque that I had loved as a student and now wanted to show my children. My daughter was surprised and asked me how I could talk to them so easily. I said the Israelis are all soldiers, in uniform or not, and they had not separated themselves from the Palestinians to such an extreme degree when I lived there and could fairly easily move between Ramallah and Jerusalem. Besides, I said to my children, I live in the future.

Above all else, what facilitates the dehumanization of the Palestinians is structural, and therefore revocable. Denying the Palestinians equal rights and civil liberties alters the way they are perceived and treated, and thereby enables the cultivation of racism against them in Israel, Europe, and the United States. Israel has always been a singular ethnocracy (one with increasingly theocratic tendencies) paraded by the Western world as a democracy: an exclusive state founded for a single ethno-religious group that must maintain its domination and majority. This can happen only by force, through sustained violence. Palestinians must be systematically dispossessed and eradicated, and a Jewish-majority state can only be settler-colonial, and with an apartheid system.

Only a single state that grants all religious and ethnic groups equal rights, including the right of return and reparations for the Palestinians, would be a democracy. Once equal rights under the law are established, children can be educated and raised differently in schools, and the older generations who were raised under fascism would quickly lose sway, as happened in South Africa (not to idealize the result, but equal rights create an important framework for justice). With the end of Zionism, the establishment of a democracy, and equal rights for all, the United States would lose the important neocolonial outpost and enforcer that is Zionist Israel, and likely much of its grip on the region. Despite Israel’s enduring policy of destruction and dispossession, Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs are today roughly equal in number on the land of historical Palestine. And barring a future tectonic shift, this land will remain in West Asia, which is known for its ocean of diverse peoples. A multiethnic, multireligious country would more readily fit into this region, which historically included significant Jewish communities.

The Palestinians persecuted and killed by the Israelis in Gaza and the West Bank enter the daily lives of Palestinians living in exile. Specific persons I see in footage now inhabit my world, and I have near-total recall of many scenes, which I play over and over in my mind, like an early one during this genocide, filmed by a Palestinian journalist approaching a young man in Khan Younes with a street cart. “Do you have bread?” the journalist asks him. “La wallah (no, by God),” he replies, handing the journalist a piece of falafel. Their exchange is accompanied by the terrifying sounds of nearby Israeli bombardment. “Do you hear that?” says the journalist. “We hear it, wallah.” “What are you doing sitting here?” the journalist asks him. The man smiles a soft, beautiful smile, and answers: “Al-mouteh mouteh wahdeh, wal-rab rab wahad.” Death is but one death, and God is one God. If these two men have since been killed outright or force-starved to death, they, and all who are killed in this Palestinian Genocide, will continue to live through us, in devotion and love.

* Israeli forces have destroyed all 13 of the universities in Gaza, yet until today, we have seen no American universities protest such destruction, and what it means for the many thousands of students who will not continue their education. [Ed.]

Beautiful article documenting a reality rarely seen in the West.

Beau récit, très bien écrit.

Merci Jenine.

Brilliant, thorough, heart-breaking. Thank you, Jenine, for the insights and the hard work. Inshallah.

Thanks, Jenine, for a wonderful and truly important article — and above all, thanks for sharing it.