A novel of Egypt, A Land Like You from Seagull Books.

Tobie Nathan’s historical novel, A Land Like You, set in Cairo in the first half of the 20th century, juxtaposes realistically rendered historical figures—among them King Farouk, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Anwar Sadat—with vividly imagined fictional characters. Chief among these is Zohar Zohar, a shapeshifting young scamp, born to two poor residents of the city’s ancient Jewish quarter, Haret al-Yahud. In the passage excerpted here, Zohar brings together his two closest friends in preparation for what will become, first an amorous adventure, and then an unlikely business partnership.

From the Balfour Declaration in 1917 through the Free Officers’ Revolution in 1952, A Land Like You explores the forces and tensions that would transform the Middle East. And in the three characters of Joe, Nino, and Zohar, Tobie Nathan suggests three possibilities for Egyptian Jews in the 1940s: Zionist; Egyptian nationalist; and apolitical survivor, loyal only to an unknown spiritual master. Though as Zohar will later say, “Egypt is my mother, the womb of all my thoughts.” —Joyce Zonana, translator

Khamis al-Ads Cul-de-Sac

Excerpt from A Land Like You, a novel by Tobie Nathan

Seagull Books, 2020

translated by Joyce Zonana

1941. THREE YEARS HAD PASSED. Dark black hair, meticulously combed and parted on the side in the British fashion; large, slightly bulging black eyes, always startled—at sixteen, Zohar had become a handsome young man of refined elegance. He wore pleated trousers that rose high above his navel, in a style set by Hollywood films; along with light, open-collared shirts, always immaculate. He never went anywhere without his two-toned shoes, clicking their metal taps on the hara’s cobblestones. And even though no one knew where he spent his days and nights, every so often he returned to sleep in Uncle Elie’s grocery, on the little bed his parents had placed beside theirs.

He continued to make and sell his cigarettes; day by day, his business flourished more and more, especially after he expanded his offerings to include less licit items along with tobacco. One night, a work night when he was roaming the city in search of customers, he had what would prove to be a fateful encounter.

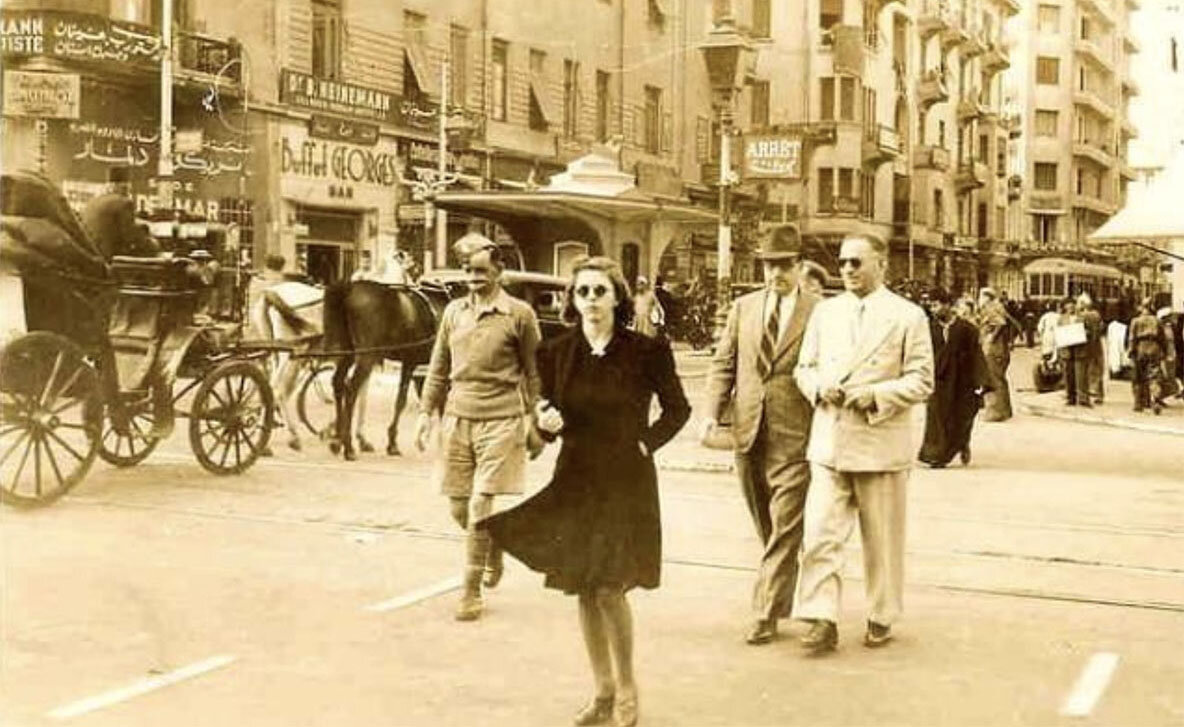

Central Cairo 1941 (photo courtesy Micky Salem)

Not far from Haret al-Yahud, in the Karaite neighborhood of Khoronfesh, a tiny cul-de-sac, Khamis al-Ads, threaded its way through the small, run-down buildings. There, in the house owned by the Karaite Samuel, lived the Cohen family, not Karaite but just as poor as the other tenants—Muslim, Copt, Karaite or rabbinate. Over the course of some fifty years, the father, Gaby Cohen, who worked for the watchmaker Moussa Farag, had ruined his eyes repairing the neighborhood’s watches. He died right at the start of the war, the day Germany invaded Poland, the first of September 1939, in the small hours of the morning. No doubt about it, he was dead too young, barely sixty years old, leaving a wife in tears, plus five grown children from a first marriage and three from a second. The oldest of the three was named Abraham or Albert—but this hardly mattered, since everyone called him Nino.

At the death of his father when he was seventeen, Nino was already in his second year of medical studies at Fouad I University on Kasr al-‘Aini Street. An intellectual, most definitely, who cared more about reading than about his studies. He read equally well in three languages—Arabic of course, but also French and English. A tall young man, strikingly handsome, the aptly named Gamal, lodged in the same building. This law student, four years Nino’s senior, had for a long time served as a mentor, recommending books and encouraging him to view life in political terms. A passionate militant nationalist, he’d led Nino to discover the biographies of Kamal Ataturk and Bismarck, the works of Karl Marx and Paul Lafargue, but also the poems of Ahmed Chawki and the novels of Tawfik al-Hakim. Gamal, who’d joined the Officers’ School, had grown scarce of late, but reappeared whenever he was on leave, and the two continued their unending discussion of Egypt’s future.

Gamal was convinced that Egypt, mother of the world, would spawn a new era—when Arabs, the wretched of the earth, would finally regain their place among the nations. Nino, who shared his ideals, asked him what role the Jews would play. Gamal replied that in Egypt there were no Jews, only Egyptians and foreigners. And he explained further—the people’s poverty stemmed from the foreigners’ brazen exploitation of resources: the British primarily, but also the French, the Turks and all the other imperialist vultures preying on the country. The new Egypt would be Egyptian.

His powerful voice carried; he spoke well, he spoke truly, he spoke for the people. Emanating from Gamal was such conviction, such authority, that Nino didn’t dare confess that he, although Egyptian since time immemorial, had no nationality—neither Egyptian nor foreign: he was stateless. Ever since the father’s death, the Cohen family’s income had been progressively reduced to a pittance, so much so that Nino took a job working as a compounder for Assiouty, the pharmacist on Nazmi Street. During the day, he worked there making lotions and creams; at night, he studied. To stay awake, he’d developed the habit of smoking hashish. Unlike his fellows who frequented the smoking dens on Champollion or Ma’ruf Streets, he smoked alone, at home, cigarettes he rolled mechanically, without looking up from his anatomy assignments. One night, when he’d gone out in search of the drug, he came across Zohar patrolling Suares Square, not far from the Italian Consulate, near the Bentzion building. Nino, his little eyes hidden behind thick glasses and his neck sticking out above a shirt with too big a collar, was so gaunt he seemed afflicted by a serious disease. He was painful to look at.

“What’s wrong, my brother?” Zohar began. “Your head seeks the vapors of the night, but your feet don’t know where to take you. I know what you need, the paste that opens the paths of the spirit, the blue dust that makes your eyes sparkle, or would you rather the jelly that makes you lustier than a lion?”

Struck by the young man’s patter, Nino smiled. And so it was another face Zohar saw, a face of intelligence and joy. It was impossible to resist Nino’s smile.

“And what would be best for me, Doctor Smoke?”

“First of all, some green, very fresh, straight from the fields of the Delta, and your week will be green. Then, you’ll sprinkle your Craven A with some blue and you’ll float on an ocean of truth. When you close your eyes, a nude woman with long hair will sit on your lap and her ass will dance between your thighs. That’s what you need, my brother.”

They walked the length of the new bridge that was now called Qasr al-Nil, chatting. Finding an intelligent and clever boy who hadn’t been to school, Nino undertook to convince Zohar to earn his baccalaureate. Zohar was happy to meet a young man who liked to talk, to debate, to prove, to argue. Nino spoke of Egypt, Zohar of the Jews; the first thrust himself into history; the second sang of origins. Nino explained to Zohar the reasons for his poverty: ninety-five per cent of the land belonged to a handful of wealthy families, who leased it to the fellahs, peasants who couldn’t even make enough to pay the rent. “Look! I’m not poor!” Zohar replied, drawing wads of bills from his pockets. “You are poor!” Nino replied. “You’re poor and you don’t know it. You’re poor because you’re all alone.” And Zohar burst out laughing, explaining that he was not alone, quite the opposite! He was a scout, the explorer assigned by the great Zohar family to discover the new Egyptian society. And he took hold of it exactly where people couldn’t resist, where they’d become slaves to their only pleasure. “What a strange idea,” Nino interjected. “Pleasure is the path to alienation.” Zohar didn’t understand the word. Nino explained: To be alienated is to lose your strength, your essence, for a third party’s profit. The fellahs are alienated because all their strength serves only to enrich the wealthy landowners. The workers are alienated because their backbreaking labor serves only to enrich the factory owner. Had he ever seen a rich fellah? Or a rich worker? No! No one had ever seen any. They were alienated. The fruit of their labor was confiscated. Did he understand that? And the Egyptian people were alienated, since the profits of the nation’s work went elsewhere, to foreigners, the British, the French.

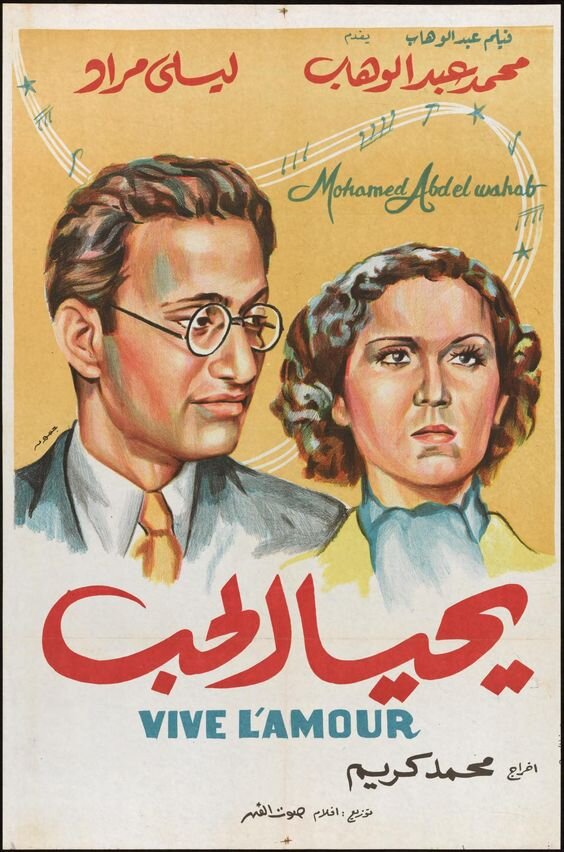

Yahya al-Hub, directed by Mohammed Karim, original movie poster of the era, starring Mohammed Abdel Wahab and Leila Mourad.

“But I have only one master!” Zohar replied.

Nino interrupted him. “You think you’re your own master? You think the profits of your labor belong to you? Is that what you think?”

“No,” cut in Zohar, “No. I have only one master and I don’t know him.”

Nino was speechless before the strange reply of his nighttime companion. He bought some green from him, hugged him, and said only “I love you, my brother!” And they walked side by side, hand in hand, as far as Shepheard’s Hotel which was open all night. They parted there, promising to find each other again soon.

Zohar frequently met Nino at night, sometimes for business, sometimes solely for the pleasure of talk. That year, 1941, war broke out in the Middle East. In accordance with the treaty signed in 1936 by young King Farouk, Egypt had been constrained to welcome British forces. Cairo was crawling with soldiers, Englishmen of course, but also Australians, New Zealanders, Indians, Poles, Frenchmen from unoccupied France. In the wealthy neighborhoods, there were now more foreigners than Egyptians. All these men, especially needy since they were separated from their families and confronted with the anxieties of combat, had to be fed, dressed, housed, entertained. Bars sprang up like mushrooms; nightclubs and brothels fell clanging onto the city. Commerce underwent an extraordinary expansion, as pounds sterling and shillings joined piastres and dollars. What’s more, everything was for sale—at a premium, and in foreign currency! From old bicycle tires to costume jewelry, from battered pots to ancient cars. Prices climbed faster than a monkey chased by a panther. The official market collapsed, the black market exploded.

Zohar’s traffic thrived now that he’d given up cigarettes as too cumbersome. He procured all sorts of drugs for military men, from hashish whose price had skyrocketed, to rarer powders he found thanks to Nino’s connections with pharmacists. Having grown rich from one day to the next, Zohar labored alone, spending his nights scurrying through nightclubs and hotel bars, here to obtain the merchandise, there to sell it. Numerous British officers relied on his services; he had entry into the capital’s exclusive clubs: White’s, St James, the Automobile Club.

Under Gamal’s auspices, Nino was meeting Egyptian military men more and more hostile to the British presence. He’d been admitted to gatherings where they were plotting against the British and against the King, where they were planning different kinds of revolution—communist, socialist, Islamic. Imbued with their ideas, Nino was beginning to long for the victory of the Axis forces: the Italians who were occupying Ethiopia, part of Somalia, and above all nearby Libya; and the Germans, whose armies were beginning to disembark in Cyrenaica, the east coast of Libya. He sometimes said strange things that startled Zohar, things like, “If we Egyptians were to sign a secret accord with the Germans, once the British were routed, Egypt would finally be independent.”

Zohar was deeply opposed to these ideas, first of all because the departure of the British would mark the end of his business. Then there were all those stories circulating about the visceral, bestial, delirious hatred of the Germans. Did he want to find himself in a concentration camp because he was Jewish? Nino would reply, “There are no Jews, only exploiters and exploited.” And the debate went on—the same, always. Zohar liked this debate, which reminded him of Rav Bensimon’s arcane reasoning about forbidden foods.

It was during that same year of 1941, in March, a few days after the announcement of General Rommel and his Afrika Korps’ victory in Libya, that Zohar introduced Joe di Reggio, his longtime friend, to Nino Cohen, whom he’d nicknamed “the Professor.” “You’ll see,” he told him, “his blood is light, like orgeat syrup, and he’s as learned as a rabbi. A professor.”

During the intervening three years, Joe had chosen a totally different path. The year before his baccalaureate, he’d suddenly grown enamored of sports, tennis and polo, which he practiced on the grounds of the Gezira Sporting Club—but above all basketball, for which he’d joined the Maccabees, a Zionist club that sought to impart its ideals to Jewish youth. There, he was part of a top-ranked team, but he also learnt songs of Jewish resistance against British occupation and began to dream of the struggle to create a new Jewish state. This sudden orientation profoundly displeased his parents—his father who despised the socialist ideas of the Jewish colonists in Palestine, and his mother, allied (at least in her mind) with the communists, and who could not understand a liberation struggle for Jews alone. She, several times a millionaire in pounds sterling, longed for a revolution sprung from the masses that would establish justice and equality for all, not just for one group. The baroness’ political sallies provoked a reaction in the salons; a scent of scandal spread all around her.

So it was that one night, all three of them found themselves at Shepheard’s Hotel—Joe the Zionist, Nino the communist, and Zohar, who was simply Zohar, Zohar Zohar.

Read TMR’s review of A Land Like You

Professor emeritus of psychology at the Université Paris VIII, Tobie Nathan is the author of a dozen novels and numerous psychoanalytic studies. Born to a Jewish family in Cairo in 1948, Nathan had to flee his country with his family following the 1957 Egyptian Revolution. Educated in France, Nathan is a pioneering practitioner of ethno-psychiatry, and in 1993 he founded the Centre George Devereux where he worked primarily with migrants and refugees. In 2012, he received the prestigious Prix femina de l’essai for his memoir, Ethno-Roman, about his life as an Egyptian Jewish immigrant in France. The original French edition of A Land Like You was shortlisted for the Prix Goncourt in 2015.