I look behind me and see my tracks, but cannot see me.

Let’s presume that your healing is complete, who then will bury the rotting corpse of the past?

I see no impurity or weakness in fear, unlike courage which I have often found to be synonymous with male folly. In fact, if anything, fear keeps you alert, vigilant, in a state of internal meditation even, one that enables you to gradually build up your psychological defenses. I refer here to a specific limiting fear; one that has nothing to do with panic, horror, or distress in response to a perceived and clear threat but one that is instead subtle and tame. A fear that, as infants, we ingested with our mother’s milk, and after we were weaned, it moved on to become a component of our daily sustenance that we were fed mixed with deception, lies and concealment, all that we relied on to survive.

A fear laden with advice such as Listen to what you’re told, Walk the line, Stay out of trouble, If a bully stops you don’t fight him and give him all you’ve got, Eat up or the food you leave on your plate will run after you on Judgment Day, If you masturbate you’ll go blind and weaken your knees, Say please, Say Alhamdulillah, Don’t discuss politics, Wear an undershirt,” etc, etc, etc, and before you know it, Boom! You’ve reached adolescence and you learn the necessity of stepping out of a traffic officer’s way should you encounter him in the street, concealing your identity from those you talk to, and never discussing religion with anyone, so that by early adulthood you find that your practical experience with fear up to that point has earned you the ability to practice life fully with it constantly by your side: You make love to your girlfriend whilst surrounded by multiple fears that begin with the neighbors potentially breaking in to the house, being stopped by a police officer in the street, a ripped condom, your friend returns home before you two are finished, for her female cousin to learn of your affair, or her mother’s male cousin to encounter the two of you together, and yet in spite of all these fears, Arab love stories persist and grow; we marry, we procreate and we separate.

A total life spent in the company of fear, for who are we to refuse the fear or rebel against it? We are a people who consume fear instead of croissants with our coffee; we are the owners of sharp and hurtful tongues that puncture holes in our bravery, strength, fastidiousness and individuality, and all our beautiful Arab values on rebelliousness, bravery, and daring feats that are invoked in the songs of Egyptian festivals in which the artists string lyrics about their ability to take up arms and see any battle to its bitter end seem in vain when someone like Captain Hani Shaker, Head of the Syndicate of Musical Professions in Egypt, hounds artists and forces them to swallow their words. Intimidated, they cave in, because they, like all of us, were raised in fear too.

I admit that the previous paragraph is long and full of scattered ideas and images, and I am aware that one of the guidelines of eloquent editing dictates that I break up my paragraphs and sentences into shorter ones. I must rid the text of everything that could potentially distract the reader from the work’s central theme. As I re-read the previous paragraph, I feel a creeping fear and hear a chafing voice that orders me “to write as one ought to, to tow the line, to define my idea, to express my thoughts minimally and precisely, to keep the text clean and simple.”

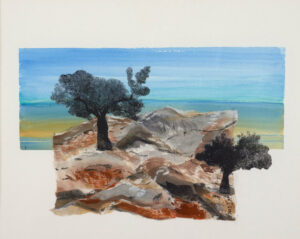

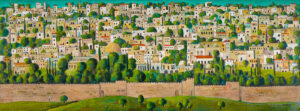

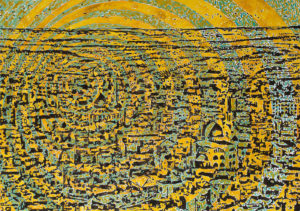

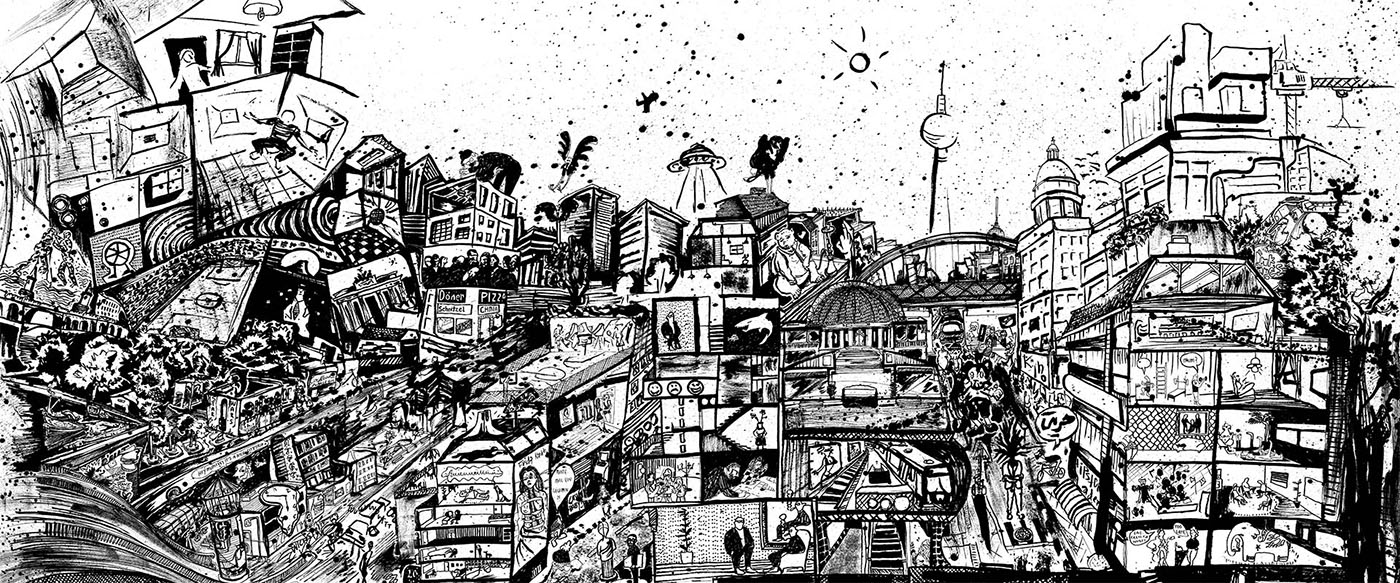

In all probability, I’ll succumb to this type of fear, solely for its novelty, a non-Arab fear if you will, one unlike the one my mother, my society and my government instilled in me, one I’ll liken to a swarm of invading ants that have stealthily taken residence, festering inside of me in the last few years since my move to America, eating away at my self-confidence, severing all communication with the real me. Are you getting any of this? Do you know what I’m trying to say? Never mind, let’s start at the beginning one more time. And yet, there is no beginning point to return to, I am in the middle, stuck with fear in a hole whose walls are screens that display urban landscapes, and stunning images of nature from the North American continent.

I Love Wasta, Hate Standing in Line in Egypt, But I Am Poor, by Ahmed Naji

Coding to the degree of encryption, excessive puns, concealing self-disorder and its paradoxes under the pretext of writing about the common human condition are but some of the consequences of growing up under rigid institutions that expected blind obedience, outcomes that have in turn metamorphosed into the essential elements that constitute the genetic makeup of modern Arabic literature. Ultimately, this may not differ much from the practices of deception, lies and concealment which we practice to survive, but the writer turns his fear and attempts to escape into art or literature or even into a muddled text like this one.

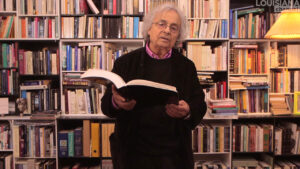

Thanks to the Internet, I mastered the art of concealment pretty early on. The Internet proved to be my hole in the wall, a way out of the isolatory cells that fear erects between individuals. In a time before social media and virtual identification, I, like everyone else, used my fair share of pseudonyms to establish my first social relationships away from family and school. As I wrote and published under many borrowed names, without the knowledge of my family or even my closest friends, I not only found my voice and writing style, but I fell in love with writing anonymously. However, when I finally chose to pursue a career in literary journalism, the detachment I had maintained between my hidden persona and the public one quickly disintegrated, until the wall totally caved in between Iblis (Satan) — my pseudonym at the time — and Ahmed Naji.

Subsequently, nearly every encounter I have had with someone who knew about my writings on the Internet, would inject their comments with words such as “young,” “quiet” and “unassuming” as if attempting to reconcile the two personas was proving too difficult. Suffice to say, that with ‘Satan’ put to rest, my name, Ahmed Naji, is what I go by on all social media platforms.

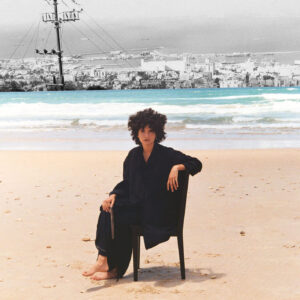

I left Egypt alone. A writer with no affiliation to any political organization, wandered astray from my religious and national groups. However, once I arrived in America, this lost all value and meaning, for no sooner had I presented myself at the terminal gates did I not only receive the official government stamp, but left the airport branded with a whorish array of labels that I never got to have a say in choosing nor could make sense of.

Soon, however, the minutiae of daily life in exile compels one, especially in the field of writing and cultural work, to gradually adapt to those labels invisibly branded on one’s backside. I recall that it was during my first few months in the country that someone asked me a question in which they referred to me as a brown writer —a term I was unfamiliar with at the time — and it was only after I asked for further explanation during which the same person stammered and fumbled to present me with an adequate answer that I finally understood it to be a term directed at writers who did not belong to the white or black race. I admit I was taken aback at first, but then I too gradually came round to accept the label as normal and life moved on, as all matters do, in the United States.

I have found that obedience and conformity in the United States are not strictly enforced or heavily guarded by armed soldiers or prisons, instead they present as a whisper, a sound vibration that crashes into your consciousness where they transform into ants that proceed to slowly and gradually eat away at your insides until they ultimately deform you after which they proceed to build you back up and mold you into what the system determines what you should become.

Eventually, I began to introduce myself as a brown writer, to discuss the collective of Brown Writers and to pepper my speeches with the exact labels I had balked at receiving upon my arrival to the country. In the US, I have, alhamdulilah, become a writer who is Brown, Muslim, Arab, Arab American, North African, and occasionally African. And, thank the Lord, I continue to amass titles and identities for they are the keys to grants, jobs, education and life. Yes. There it is, the deceit, yet again, only this time it appears to face a new kind of fear.

Besides, who are you? Do you deny that you are a brown writer? Do you deny your ethnic origins? And why do you criticize Arab Americans? Are you ashamed of your tribe? How ungrateful of you. However, if you do not identify as Arab, then why speak for them? If you do not identify as queer, then why discuss anal fucking? You have no right to that conversation. Except of course you do because freedom of expression is after all guaranteed for all. However, if you do choose to talk about something like your deference to consumers of fisikh (a certain type of fish in Egypt) for example, then you better make sure you actually eat them yourself or else it would seem that you are stealing someone else’s voice and appropriating their space. And what about residency papers and a work permit? Not until you prove you can indeed assimilate by ceding that you are a brown writer, an Arab, a Muslim, she/them/he/her. Listen to me, you sons of bitches, I was breastfed on trickery with mama’s milk, nothing is simpler than for me to lie my way through your stipulations and conditions.

The first time I used the Internet, I was twelve years old. In September I turned 36. Last year, for the first time, I became afraid of the Internet. More than once, I caught myself posting on Facebook or Twitter, only to return to my posts days, sometimes hours later, to delete or hide them in the archives. Although what I write does not touch upon politics, religion, or any of the prohibitions, yet fear, the kind of which I have not experienced until now, overwhelms me and compels me to erase what I’ve written.

The fact that I never did this when I was living in Egypt scares me. It frightens me even more that I don’t know the source of my fear, its cause or where it comes from. In Egypt, the sources of terror were known and one was cognizant of the limits of their reach and thereby they could be circumvented.

However, in exile, fear springs from within; from the temporary identity papers that they give you, from the invisible shifting land under your feet, from your alienation, not only from the place and the social and cultural environment in which you grew up, but from your estrangement from the self you spent a lifetime building and now barely recognize.

I glance behind me and see my tracks, but cannot see me.

Forced migration is like an axe that incessantly hacks away at a writer’s work and literary style. In my early days, my optimism level was almost sky-high. I thought of immigration as an opportunity for a new beginning, and who among us does not like new beginnings? Unbeknownst to me that it would instead prove to be the start of my “great wander.”

The more one familiarizes oneself with the processes and ways that cultural institutions in the country of exile operate, the more one realizes the impossibility of starting over, of reproducing oneself anew as well as the impossibility of reclaiming the old self. And thus began my steep descent into the depths of a labyrinth in which I felt like someone had stripped me of ownership of my language and erased the historical dimension and the geographical context from which my knowledge derives its strength. It’s when life’s necessities present themselves that the chasm further deepens for a writer in search of a new voice and yet is obliged to practice within a cultural machine that provides marginal spaces for immigrants to exist, thereby pushing everyone to compete with other foreign writers like themselves over what little scraps they can secure.

Under such circumstances, exiled writers are wary of rebelling against the system, straying from the conventions of proper writing, or even throwing in the towel altogether for fear of losing their only source of income, forced to join the crowds of other immigrants scrambling to find work. Many a time I’ve asked myself why I cling to my profession after all the heartache it has brought me. I surmise I’d make more in a month working as an Uber driver or supermarket employee than I’d make in a lifetime of writing before sobering to ask myself: What after eight hours of physical work a day and scheduled visits to a psychiatrist to numb the internal pain to prevent me from taking my own life, would remain of me?

Psychiatry did not develop to deal with immigrants and expatriates, and is therefore incapable of bridging the gap between immigrants and the new societies they find themselves in, as it was never designed at its core to ever acknowledge them.

Are you having panic attacks? How do you feel about meditation? The situation is precarious, so a visit to a doctor or a psychiatrist may save you from all your pain and existential questions.

I refuse to visit any medical professional unless physical symptoms appear on my body. As expatriates, it is my reasoning that we must approach psychiatry with caution. However, this is not an invitation for you to share in my contempt of the profession, but advice for you to exhibit caution should you decide to give it a go.

I believe that the ultimate goal of psychiatry, as a byproduct of modernity, is to help individuals overcome their paradoxes and mental anxieties, averting them from causing harm to themselves and others thereby allowing them to live in harmony within their surroundings.

It is worthwhile noting that the accumulation of knowledge in psychiatry is based on decades of study and analysis of individuals born and raised within nation-states as well as institutions of liberal modernity with the aim of helping these individuals to become active members of their community. In essence, psychiatry did not develop to deal with immigrants and expatriates, and is therefore incapable of bridging the gap between immigrants and the new societies they find themselves in, as it was never designed at its core to ever acknowledge them.

That said, it becomes less surprising to learn that some of the consequences to this oversight in the system is the sharp rise in suicides among immigrants when compared to the total population, closely followed by psychological and emotional trauma. And supposing that an immigrant were able to secure the legal and professional status necessary to acquire health insurance, then begins the even more despicable journey of visits to psychoanalysts and psychiatrists, who not only cannot speak foreign languages but also have little, if any, understanding of their patients’ culture and thereby serve no purpose but to deepen the emotional rift lodged within the immigrant.

And yet, under the pressure of hope for survival, the immigrant, now turned patient, fumbles under a foreign language to communicate, striving to rebuild a new self from the psychoanalyst’s sofa. I ask you, what could this health professional offer someone like you who has lived through war, rebellion and prison when he knows nothing about them? Will he really solve your problems with his foreign diagnostics and treatment protocols? Do you honestly believe that the road to your salvation can only begin after you succumb to mimicking the symptoms of a psychoanalytic diagnosis imposed upon you? Is the analyst’s role simply to guide you into talking your way to a more civilized, culturally amenable self than the one you arrived with and which the new system expects you to shed and leave behind? Might not your belief in the psychoanalytic process be a byproduct of expressing yourself in a language other than your mother tongue?

I recall an incident with one psychoanalyst who launched into a long-winded explanation on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), suggesting coping mechanisms regurgitated in many a self-help book and the novels of Paolo Coelho. I sat, restraining my frustration, plastering on my face a polite immigrant smile before I was finally able to thank him for his truly enlightening speech but without failing to explain in return that indeed the operative words in his diagnosis of my condition were “Post Traumatic,” and therefore I promised that as soon as I got over my trauma, I would return to him for therapy. What dumbass psychoanalysts like him fail to grasp is that an immigrant exists in perpetual trauma; every day in exile is one kind, your assistant’s slow drawn out sentences she uses to address us when booking our sessions is another one, sitting opposite you explaining myself in a foreign language is the ultimate personification of trauma. And the insistence of Western psychoanalysis to implement the PTSD protocol is biggest proof of its fecundity, arrogance and presumptuousness to view their country as a paradise and the immigrant as a victim who needs to be healed, cultured, tamed, before he is worthy to join the ranks of other citizens who enjoy the benefits of that paradise.

But let’s assume, on the odd chance this therapeutic method works and you do heal internally, enough for you to reach a point where you are able to convince yourself that you do belong in this new society, no different from everyone else. Who, pray tell, will bury the rotting corpse of the past lodged inside your ribcage?

“Taming of the Immigrant” originally appeared in Arabic in Aljumhuriya and was translated for TMR by Rana Asfour.