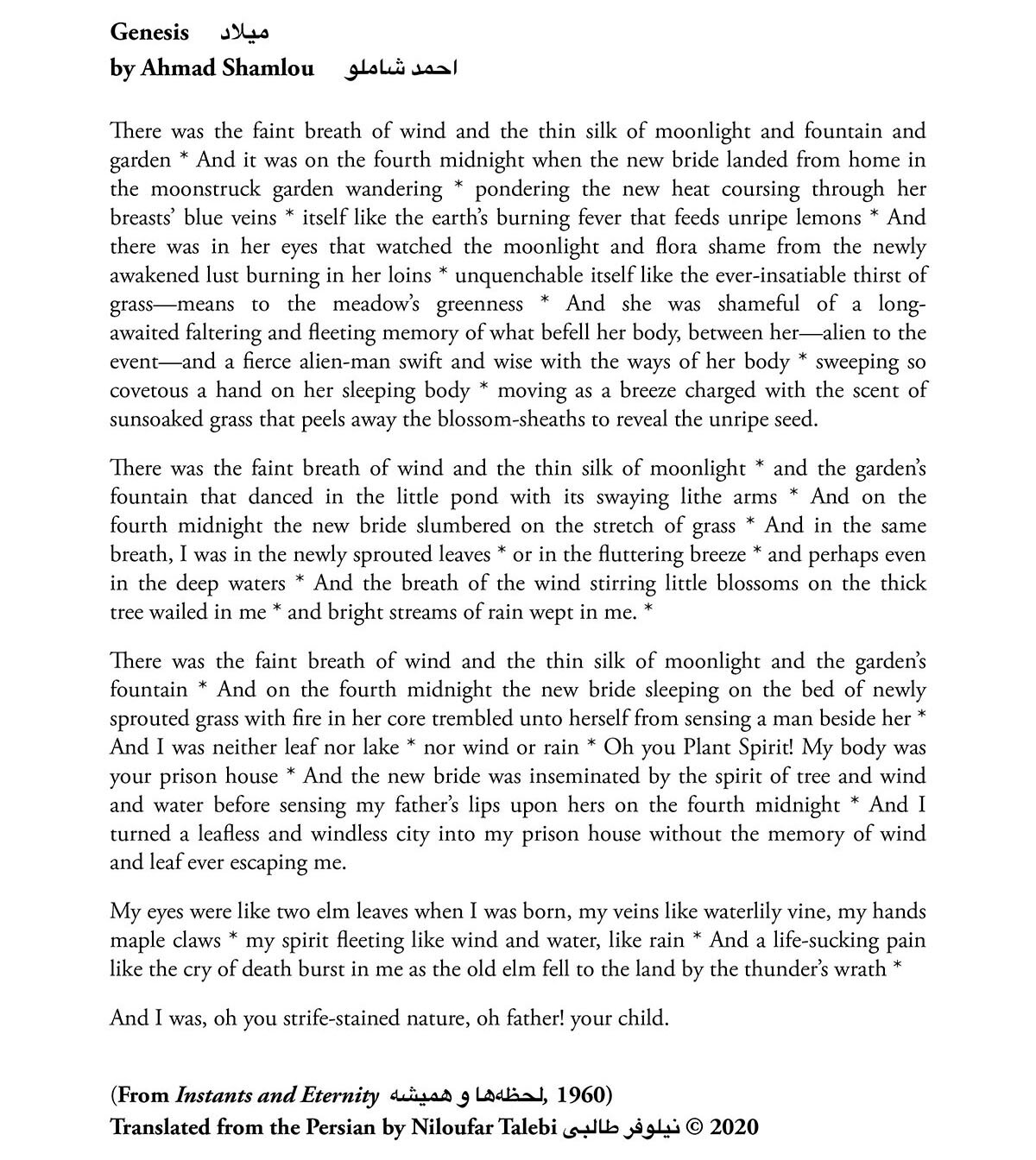

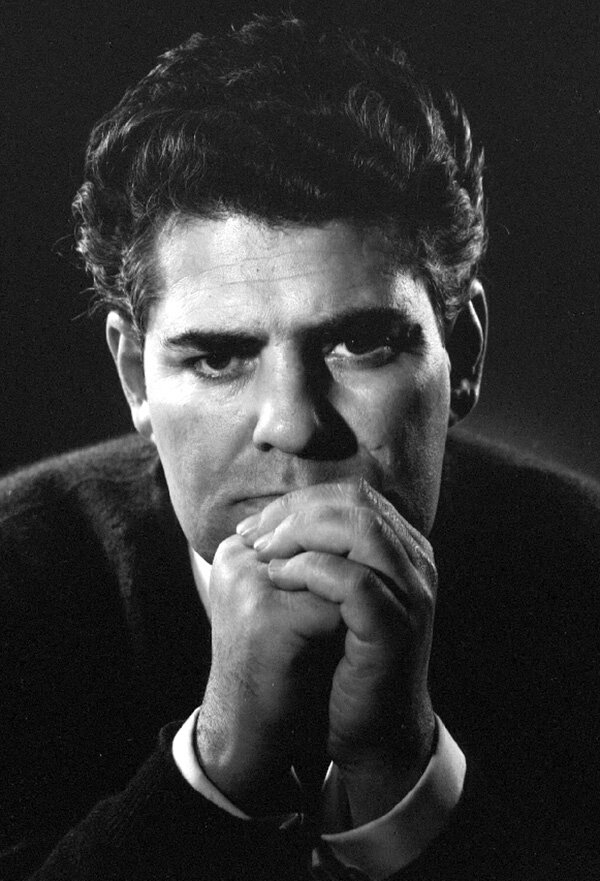

Reflections on Ahmad Shamlou at 95

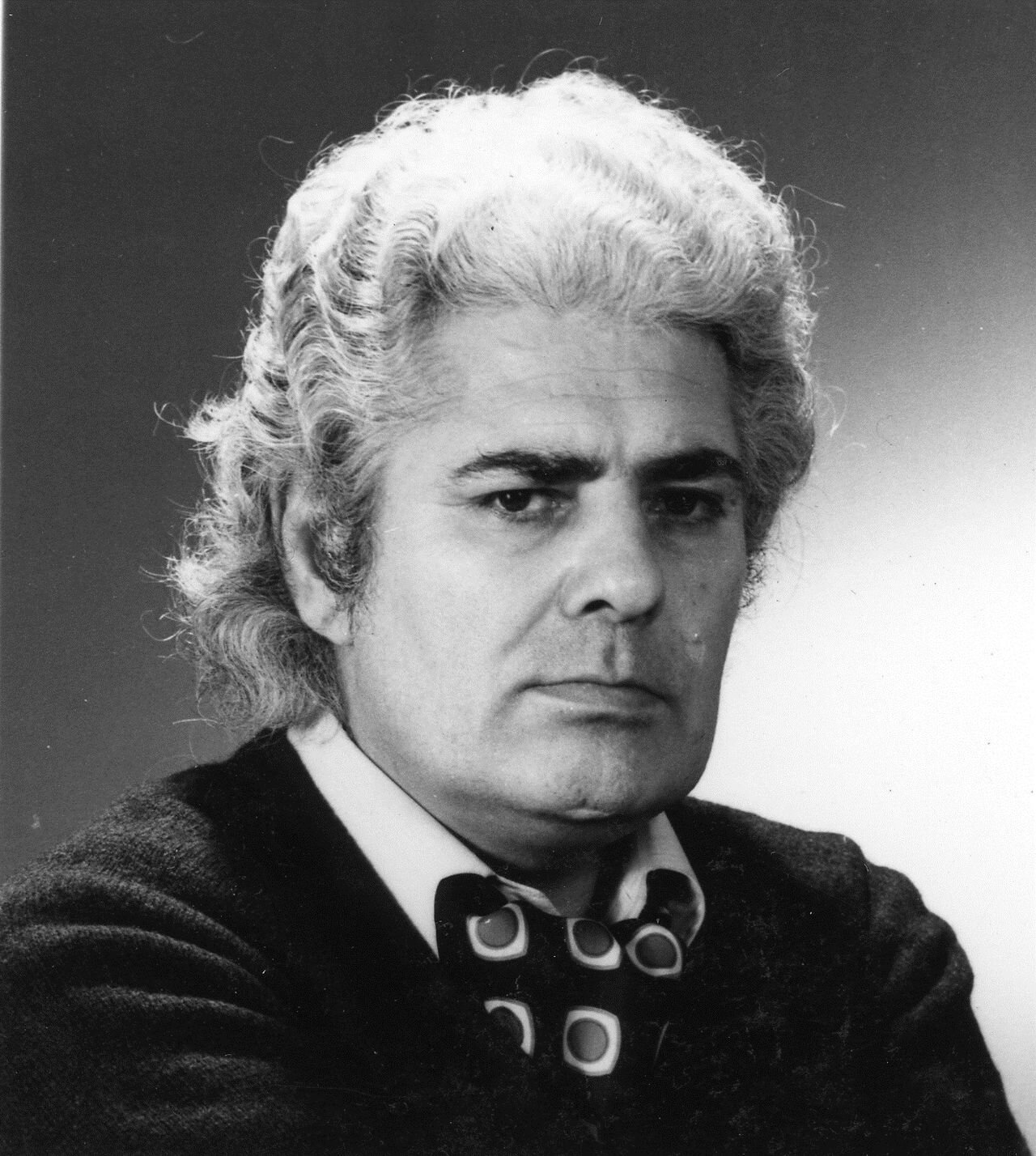

The Markaz Review is pleased to bring you this commemoration of Ahmad Shamlou by translator, Niloufar Talebi, who grew up in Iran at a time when Shamlou was a family visitor. Last year Talebi published a unique genre-busting memoir, Self-Portrait in Bloom, that melds her own history with the trajectory of Shamlou and his extensive body of work. As a translator, author and San Francisco-based interdisciplinary artist, Niloufar Talebi is sui generis. She’s also a generous lover of words who earlier this year gave us the comprehensive 100 Essential Books by Iranian Writers: An Introduction & Nonfiction, published by the Asian American Writers Workshop and widely shared by LitHub, Pen American Center and others. This offering includes Talebi’s introduction to Shamlou, along with an excerpt from her book and two translations, of “Hamlet” and “Genesis,” plus their video complements. (Ed.)

Niloufar Talebi

December 12, 2020 marks the 95th birthday of the revolutionary and controversial Iranian poet, translator, essayist, editor, encyclopedist, and cultural figure, Ahmad Shamlou (1925-2000).

The great life work of Shamlou was to create a new poetics for Iran. By force of talent, personality, and will, he drove Persian poetry from its early steps away from classical forms—preserved as if in amber—all the way to free verse. He had partners in this work, of course, including his predecessor and mentor, the poet Nima, who arduously set this revolution in motion, but Shamlou’s great project was a synthesizing of Western and Eastern canons and artistic movements to incite this cultural revolution, which updated both poetic form and content to fit a post-industrial 20th century. In this way, Shamlou’s work belongs to the world. But despite garnering several international awards, including a 1984 Nobel Prize nomination in Literature, Shamlou isn’t yet a household name to Western readers, the way, for example, Neruda is.

Shamlou’s genius of creation and destruction led him to challenge nationalist readings of classical Persian poetry, and criticize traditional Iranian art music for merely passing down forms from generation to generation without introducing innovations. And this would gain him critics even amongst the intelligentsia, who could not reconcile the contradictions of what Shamlou was—a fierce lover of Iran and its people and yet a staunch opponent of crude nationalism, a voice open to the influence of art from the West while categorically rejecting colonial attitudes toward literatures of the East, a socially-conscious artist of his time concerned with humanity’s struggle for liberation and yet a poet following the call to beauty. One thing is undeniable: Shamlou’s direct line to our collective unconscious is why his poetry is universal and immortal.

In the following excerpt from Self-Portrait in Bloom, my memoir that defies the genre to present a bio-portrait of Shamlou, a selection of his poetry in my translation, and my memories of a youth spent in Iran around Shamlou who visited my childhood home, I delve into some of the many dualities that Shamlou embodied.

A Shamlou excerpt from Self-Portrait in Bloom

“SHAMLOU HAD THE UTMOST FAITH in the richness of the Persian language and its expressive abilities. Reciting poetry in such an imagistic language, he said, was his pleasure. If each generation’s responsibility is to create a new language, a tool that captures and expresses the new needs and experiences of that generation, then Shamlou not only accomplished this for his own, but his shadow was so imposing that the generation following him was challenged in extricating itself from it.

He worried that his influence might have cost a generation valuable time. Daily life was enough of a drain on artists’ time—not on the merchants’—and he lamented that censorship had cost Iran’s thinkers much precious time.

Versed literature was not necessarily poetry to Shamlou. To him, the greatest damage to language was the inability of poets to innovate imaginatively in language, perhaps from a fundamental ignorance of it. Shamlou worried that the absence of meter in his poetry had misled the newer generations to bypass the crucial step of learning craft, as he had done before breaking the rules, instead expressing themselves in unmetered language not built upon the foundations of language.

Shamlou had embarked on designing a new mosaic from old tiles. His poetry at once elevated and popularized poetry.

He wrote that after a centuries-long period of dormancy, Iranian poetry had undergone an awakening, shining in the landscape of world literature on its own merits, owing its powers to ideas synthesized from both international and domestic aesthetic and intellectual movements.

And although Shamlou’s first exposure to modern poetry came through Western poetry, he resisted the charge of Westernization or “Westoxification” (as coined by the Iranian writer Jalal Al-Ahmad).

He poignantly remarked that unless Iranians count the adoption of various industries including textiles, oil refineries, airplanes, automobiles, and elevators as a Westernized practice, unless they limit their weaponry to swords and spears or limit medicine to the tinctures and distillates of yesteryear, they were, in fact, participating in a global trade of cultural collateral in the same way that science and industry were traded. Humanity progresses in sync, he said. Anything short of that would be severing Iranian society from the whole of humanity, a self-sanctioning.

And at the same time, Shamlou resisted being “othered” by the West. In May 1976, he delivered a speech at the joint PEN American Center and Princeton University event on the subject of ‘Contemporary Literature in the Middle East’:

“In my country, a Muslim-majority country, the Koran is considered a miracle. This is easy to say, but beyond the obvious lies something astonishing.

“In my country, there are many figures belonging to the rank of miracle-makers. Those known in the West are the prophet Mani and his miracle, the holy Book of Arjang, as well as Rumi, whose status as a prophet is certifiable. Hafez, the fourteenth century poet of a divan of ghazals, is also known here in the West. In my country, he is known as ‘lisan al-ghayb,’ meaning he who speaks of mysteries, which in my opinion means more than a prophet, it’s really the speaker of a ‘language of god.’ So in my country, the Koran and the Divan are of the same stature.

“I know I am a poet saying such things about poets, but please disregard that in favor of the truth. In my country, people deem poets as prophets onto whom they bestow enviable love. If a poet has passed their ruthless judgment and been accepted as a poet, and if the poet is not a follower of common traditions, then that poet is elevated to the status of martyr. In Iran, my country, a poetry reading is nothing short of an EVENT. The young generation still remembers the poetry festival that Khoosheh journal co- organized when I was its editor-in-chief as an unforgettable memory. During the festival week, 2,000–3,000 young people gathered at the civil servant’s garden from 6 p.m. to midnight to hear dozens of poets who had paid their own way to Tehran from all corners of Iran. So I don’t see any reason to waste your precious time here to tell you how I see poetry. From a craft standpoint, it is the artistry of language, or something like that. Either way, I am not a poetry critic. I live in a terrible world, worse than terrible—looking at the world with two open eyes, rage and desolation eat me alive, and I, with thirty-two teeth, my own liver. The people of my country expect miracles of their prophets. And let me tell you with deep pride—for even if you speak different languages, you still have the same heart—that your contemporary poets in Iran have accomplished, without an ounce of pride and self-promotion, such miracles, the products of their creativity and innovations such that rival the linguistic prowess of Ferdowsi and Hafez.

“So let me summarize: Poetry is whatever it is. Contemporary poets in Iran have accomplished the task of bearing noble witness to their times.”

<pdata-rte-preserve-empty=”true” >

Nearly a century since Shamlou’s birth, the question is not whether he can be summed up as being X or Y. The right question is a third, broader one: how can the multitude layers of a mastermind be gifted in as many languages as possible to the world? —Niloufar Talebi