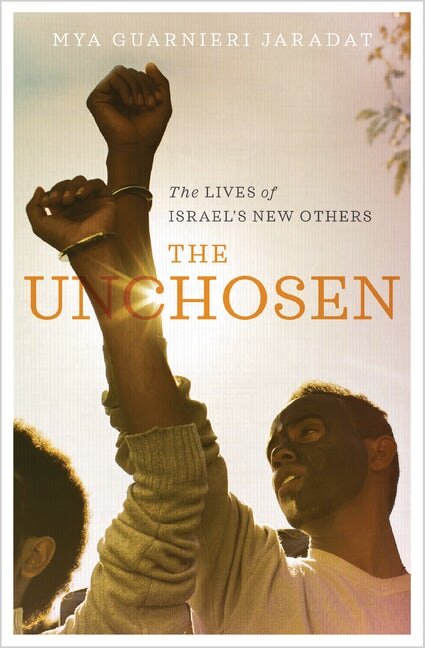

Mya Guarnieri Jaradat

Rural Georgia seems like an unlikely place to flashback to the Mediterranean city of Tel Aviv, Israel. But that’s what happened in December when I attended a political event at a Baptist church in Dalton. As I spoke to an attendee — a middle-aged man who felt that Christians are persecuted and who likened the struggle for political power in the country to a battle between good and evil, dark and light — I was transported to another December and a protest I’d covered almost a decade earlier in south Tel Aviv.

In that impoverished part of the city, locals, accompanied by right-wing politicians from elsewhere in the country, took to the winter streets to march against the presence of African asylum seekers. It was Hanukkah, and the demonstrators married the symbolism of our holiday — which revolves around light — to their agenda of seeing African asylum seekers removed from the neighborhood and deported from the country. They held signs that read “Expel the darkness — deport Africans.”

A heated argument broke out when the march ended in south Tel Aviv’s Levinksy Park, where many homeless African asylum seekers lived at the time. But the fight wasn’t between demonstrators and Africans but, rather, among Israelis themselves. A small group of counterprotesters reminded their countrymen that the exhortation to care for the strangers among us appears in the Hebrew Bible more than any other commandment. We, too, had been strangers in Egypt, they said. Not only that but the modern state of Israel had been founded by immigrants, many — if not most — of whom had fled persecution themselves. “Where did your grandparents come from?” counterprotesters asked. Hadn’t our grandparents once been strangers to these shores, seeking refuge?

— • —

What I witnessed that night in south Tel Aviv was nothing less than a battle for the twin souls of the nation and Judaism, for in Israel the two are explicitly conflated, the country a self-described “Jewish and democratic state.” But could the government privilege a certain group while remaining democratic? At what cost? Who pays the price? Isn’t “Jewish and democratic” a contradiction in terms? Even the Knesset has its doubts, with its website stating “the attempt to reconcile the Jewish nature of the state with the political rights of the Arab minority faces serious challenges.”

Swap out Israel for America and Jewish for Christian and, voilà, you have the current debate surrounding white Christian nationalism, with one side arguing that America is and should be a Christian nation while the other side argues that this easy conflation between the state and a religion is a distortion of Christianity, as well as a threat to both Christianity and American democracy. The key difference is that, in Israel, Jewish nationalism or Zionism is the official stance and has been since day one. As such, we can turn our eyes to Israel as an example that offers us stark warnings about the dangerous conflation between religion and nation, and what happens when religious nationalism becomes an inextricable part of the country’s democratic institutions.

The similarities and differences between the U.S. and Israel are too many to list. But a few are worth discussing because they illuminate the parallels between white Christian nationalism and Zionism. First, the founding myths that are a cornerstone of both ideologies: the narrative of a persecuted people who came to a land that was (wrongly) considered mostly empty and who, thanks to divine providence, built a great nation. Former Congresswoman Michelle Bachmann recounted the American version of this story at length on that December night at the Baptist church in Dalton, Georgia, as she discussed the pilgrims, the Mayflower Compact, and charged that now Satan was trying to snatch the nation away.

But this simplistic narrative elides both nations’ original sins vis à vis race, and the roots of the injustices that continue to plague both Israel and America today — perpetuated by both Zionism and white Christian nationalism. In the case of the United States, the country and many of its institutions were built on the backs of African slaves and that racism became inextricably bound up with white American Christianity, as Robert P. Jones argues in his book, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity (Simon and Schuster, 2020). And of course the wholesale dispossession of Native Americans is an oft-neglected part of this story, as Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz made clear in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Beacon, 2014). In Israel, the War of Independence, which took place from 1947-1949, created some 700,000 to 800,000 Palestinian refugees — an event Palestinians remember as the nakba, the catastrophe (cf Ilan Pappe, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, One World, 2006).

Race-based violence is woven into the DNA of both countries.

— • —

Because the modern state of Israel was founded in 1948, many believe it to be a country that rose from the ashes of the Holocaust. But this is not the case. Rather, the first Zionists arrived in the late 1800s and began building the agricultural settlements that served as the backbone for the Jewish state. An explicitly Jewish project from the outset, their relationship with the local, indigenous population of historic Palestine was immediately fraught. While some of the earliest settlers employed Palestinian laborers, this idea was quickly nixed in favor of avodah ivrit, Hebrew labor. Not only did the new Jewish settlers buy Palestinian lands from wealthy owners but they displaced the fellahin, the peasants who lived and worked those lands. Dispossessed, unable to make a living, (doesn’t the struggle always boil down to those basics: bread and work?), they coalesced into a “landless class” that grappled with unemployment and poverty and, thus, the seeds of the conflict that lasts until today were sown.

Tel Aviv, the first Hebrew city, was founded in 1909, explicitly to separate the Jewish population from the Arab. Well before the Holocaust took place in Europe, many Palestinians understood that the new Jewish settlers in their midst didn’t just want to farm a little land and live in an isolated Hebrew city on the coast of the Mediterranean. They wanted to build a national homeland — a Jewish state — on top of Palestine. This realization led to the riots that broke out in Palestine in the 1920s, as Arabs protested large scale Jewish immigration and growing Jewish hegemony. The riots continued throughout the 1930s and led to the strengthening of the Palestinians’ own national movement for a homeland, out from under the yoke of the Ottoman Empire and British occupation, as Rashid Khalidi explained in his now-classic book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness (Columbia, 1997).

So, in Israel, the idea has always been to be explicitly Jewish and this has always been articulated. In the US, on the other hand, whether or not our founding fathers intended for the country to be Christian, as many white Christian nationalists claim, is still hotly contested. According to Steven K. Green, author of Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding (Oxford, 2015) and director of Williamette University’s Center of Religion, Law and Democracy, the idea that the founding fathers intended America as a Christian nation is a bit of historical revisionism — a myth that, nonetheless, took root early on. The second generation of founders, he argues, projected this upon the first.

It’s worth adding here that, among Thomas Jefferson’s many books was a Quran; reading his 1786 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom — the forerunner of the First Amendment —quickly dispels the idea that he sought to privilege Christianity. Rather, it makes plain his abiding belief in the separation of church and state.

— • —

Another key difference between Zionism and white Christian nationalism is that while Israel was conceived as a Jewish state right from the start, the early conception of Israel as a Jewish state was not as a religious Jewish state but a secular one that would incorporate Hebrew as the national language, along with Jewish symbols and holidays. The driving idea was that Jews were a people bound together by a common heritage rooted in a particular religion, not that we were or wanted to become a particularly religious people. In fact, the religious Jews who lived in Palestine even before the arrival of the first Zionists were conflicted about the project — and they remained so as the first Jewish yishuvim, settlements, and kibbutzim, collective farming communities, were being built. Likewise, many religious Jews in the Diaspora remained opposed to the Zionist state. Case in point: in 1948, my grandfather, a 16-year-old first generation American, wanted to leave his home in Brooklyn to join the Jewish forces fighting in Israel’s War of Independence. A good Jewish boy, he of course asked his mother for permission. An Orthodox Jew from Poland, she quickly rebuked him. Only God could bring the Jews back to the land she insisted; a man-made Jewish state wasn’t kosher.

But the 1967 war changed everything.

Many Jews viewed Israel’s lightning-fast if pre-emptive victory against Egypt, Syria and Jordan as a miracle or a sign that God was, indeed, on the state’s side. Not only did Israel win in just six days, the ensuing Israeli military occupation of the Sinai, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights (the Sinai was later returned to Egypt) pushed the country’s de facto borders far beyond the Green Line set in the 1949 armistice agreements, doubling the young country’s territories. The expansionist agenda that has resulted is tinged with religion (think Manifest Destiny).

That’s when religious Jews, for the most part, got on board and Zionism began its move away from secularism, a drift that continues today and that is a source of conflict inside of Israeli society itself.

Though the Palestinians who lived through the nakba would argue that everything that has come since 1967 has just been more of the same, many observers, Jewish and non-Jewish, believe that the convergence of religion with nationalism has created an even more virulent, violent form of Zionism.

All of this has leaked back inside of the Green Line to impact the democratic institutions and Israel proper. As Israeli laws and judicial rulings go ignored in the occupied Palestinian Territories — and, occasionally, inside of Israel as well — the High Court has been weakened. Israeli society has increasingly become openly racist, with rabbis issuing religious edicts that forbid Jewish Israelis from renting to Arabs and migrants, with protests against miscegenation and vigilante groups hunting for mixed couples. During the 2015-2016 Knife Intifada — a series of lone-wolf attacks carried out by Palestinian youth, armed with knives — Israeli leaders called on citizens to arm themselves. Some critics likened this call to a green light to conduct extrajudicial killings.

Israel has also become hostile to foreigners, even those fleeing genocide, and this takes us back to that Hannukah night in south Tel Aviv. While the politicians present at that protest were mostly from the fringes of the far-right, mainstream leaders jumped on the issue to score cheap political points. Six months later, at another anti-foreigner rally in south Tel Aviv, Miri Regev — a member of PM Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party — would call Africans a “cancer in our body.” Tensions boiled over and protesters raced through the streets, smashing windows of African-owned businesses and cars and attacking African asylum seekers.

But the violence didn’t end there. Rightwing Israeli extremists have attacked African asylum seekers numerous times since; in 2014, for example, an Israeli man stabbed an Eritrean infant in the head. And, of course, the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory grinds on with no end in sight.

In Dalton, listening to the all-too-familiar rhetoric of persecution and exceptionalism, and the need to ensure a religious definition of the state, I felt violence on the horizon. The January 6 mob at the Capitol did not come as a surprise. And unless white Christian nationalism is brought to heel, there will be more to come.

In Israel, the 72-year-long experiment in being both Jewish and democratic has resulted in what some experts have taken to calling an “ethnocracy.” Others, like Dov Khenin, discuss Israel as a state with a defined, and rapidly shrinking, democratic space. Yet according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s annual Democracy Index, Israel is not a full democracy but a “flawed democracy.” It’s worth noting that, already, America like Israel is not defined as a full democracy, either. According to the same index, we, too, live in a “flawed democracy.”

Right now, in America, we’re at a crossroads. We can work together to root out Christian nationalism and address the original sin of racism. We can tamp down on populist politics, turn away from discord, and reach across the partisan divide to urge discourse. We can ensure religious freedom for all, just as our founding fathers intended. Or we can let white Christian nationalism flourish and brace ourselves for the unsurprising consequences.