A lavish coffeetable book examines the sustainable building practice of Jordanian architect Ammar Khammash.

Ammar Khammash: Notes on Formation, edited by Raafat Majzoub

Dongola Limited Editions 2023

ISBN 9789953970073

Mischa Geracoulis

In the first book in Dongola’s new series on architecture, Notes on Formation, Raafat Majzoub examines purposes and techniques of renowned Jordanian architect, anthropologist and artist Ammar Khammash. The recipient of the 2019 Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, Khammash has much to offer a climate-chaos-stricken planet through his projects such as the Wild Jordan Center and the Royal Academy for Nature Conservation, among many others. Majzoub, himself an architect and editor-in -chief of Dongola’s Limited Editions, borrows from Khammash’s early writings on Jordanian rural dwellings, Notes on Village Architecture in Jordan, to craft the semi-eponymous title, which places “formation” at the center of Khammash’s architectural theory and practice.

Instead of advocating for a particular style, Majzoub’s focus is on the ways and means in which buildings have come into existence in the Arab world. And while process is prioritized over finished product, Khammash’s completed designs and structures are intrinsic to this discourse.

The region’s architecture is necessarily interdisciplinary and intersectional. Even the most contemporary of landscapes and cityscapes are in contact and communication with ancient history and heritage. Buildings here serve not just current needs but are long-term alterations with measurable impacts on the landscape and history. A theme quickly emerges, indicating that for any architectural endeavor to be successful, the climate and terrain, societal and economic systems, and natural and spiritual worlds are essential considerations.

Discussions on formation are inevitably about information, form, and function. Khammash, however, first defers to nature as his mentor and point of reference. Formation is not a linear calculation. Larger contexts and the elements within generate a type of call-and-response that requires information gathering across disciplines to gain a more holistic vision of what’s possible, and more importantly beneficial.

Trained in architecture and ethnoarchaeology, Khammash also looks to the earth and social sciences to assess how harmony among a structure, the land upon which it’s built, and those who use it may be best achieved. One such example involves his contribution to research on the Rheum palaestinum (desert rhubarb) and the plant’s self-irrigating system. Utilizing three-dimensional modeling software, Khammash’s work helped to prove the rhubarb’s ability to capture and condense water from the air and then channel it into the root system. For builders in the desert on an increasingly overheating planet, rife with both droughts and floods, self-irrigating systems like the Rhem palaestinum’s are invaluable to discussions on sustainable development.

Majzoub writes that Khammash resists labels, both for himself and his works. Early in his career, Khammash made a judicious choice to keep his architectural undertakings separate from his artwork. Perhaps due to his experience as an inhabitant of the places in which he works, he insists on being “very careful not to cross the line … Architecture is problem-solving. Art is problem-making.”

The conversation between Majzoub and Khammash suggests the use of “design thinking strategies.” Design thinking, inspired by societal and ecological needs, requires keen observation and an understanding of lived experiences, which in some cases inevitably challenges norms. The Centre for Architecture and Human Rights (CAHR) contends that that is exactly what comprehensive design and development should do. According to CAHR, development-induced displacement is as culpable as conflict and climate change in forcing people from their homes, and therefore recommends a rights-based approach to building.

Khammash’s habit of taking his clients’ personal experiences, concerns, and needs into account before embarking on projects could brand him as a design thinking strategist and rights-based designer — even if he eschews those labels. Whether Khammash is consciously following CAHR directives or simply his own sensibilities, the Jordanian architect looks at the impacts of construction “in terms of social justice and labor” before committing to a project.

When working on heritage conservation projects in traditional villages, he consults and employs locals. Reminiscent of Paulo Freire whose groundbreaking, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, began with rural communities in Brazil, Khammash appears to share Freire’s belief that everyone has the potential to be both teacher and learner. Khammash’s projects in Jordan often generate opportunities to exchange knowledge with village elders and adapt generations-long methods to modern designs and engineering techniques.

His use of reclaimed materials and repurposed structures in the sixth century Church of Apostles in Madaba is a case in point. Blending high and low technologies, the original Byzantine construction provided foundational support for his renovations. As Majzoub explains, this method of architecture functions as a continuum, bringing the past into the future.

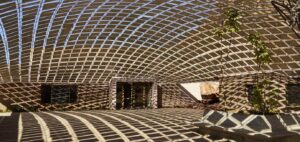

During Khammash’s restorations at Pella Rest House in Tabqat Al Fahal, workers were instructed to build “in the way their grandfathers did … to combat ‘fake heritage,’ construction [that was] meant to lure tourists into remote villages while destroying those villages … and ignoring their lineage.” Restoring ancient sites by traditional means prevents the obliteration of local knowledge. The integration of tradition and modernity actually serves multiple ends — the decision to use bamboo in the construction of Pella’s vaults, for instance, became an investment in the local economy through the purchase of bamboo from nearby villages.

Another past-to-future project is depicted in a photograph from the 1980s that shows a man plastering a structure with his bare hands and mud. This image that represents ten millennia of human technology also reflects a return to ancient wisdom for help with repairing damage done by centuries of colonialism and industrialization.

The intention of the Dongola series is to celebrate groundbreaking architects from the Arab World; and this first book manages to champion both design thinking and rights-based development. Khammash’s emphasis on construction that abides within international human rights standards and social, environmental, and labor justice is apparent, and the tribute is well deserved.

Admittedly, upon first reading, Notes on Formation’s portrayal of Khammash is overtly laudatory. For good reason it turns out, as a closer analysis of Khammash’s preoccupations with the formation and evolution of the nature, tribes, and creations of the Arab world eventually unfold like a roadmap to solutions. Still, Majzoub’s description of Khammash’s process as “effortless,” even for the award-winning architect, seems overstated. More likely, after years of immersion in the field — and imaginably, degrees of dogged trial and error — Khammash has developed his own rhythm and flow, casting an outer appearance of ease.

Bearing in mind that Majzoub himself is an artist, architect, and writer — in addition to serving as the book’s editor — his florid writing disproves assumptions that an architectural text should be dry or technical. Lavish in philosophical quotes, exquisite imagery, and rare archival materials, Majzoub’s rendering does justice to Khammash’s pioneering and poetic spirit, and treats readers to the art of Arab storytelling. With art direction by the award-winning Iranian graphic designer Reza Abidini, the coffee table-stylized book exemplifies formation. It is a meticulous presentation on construction, functionality, and beauty with a glossary afterword that confirms the text’s educational and aesthetic, value.

Notes on Formation asserts that architecture in the Arab world is ultimately called to raise questions, bend rules, and forge stronger connections between the past and present. By positioning architecture as a disciplinary force for change in the region, it provides, according to Majzoub, “a much-needed public pedagogy.” Creating new municipal spaces while simultaneously preserving cultural heritage sites opens possibilities for critical conversations on collaboration, cultural transmission, and human relationships with the environment, changing climates, and societies within and beyond the Middle East, North Africa, and Southwest Asia.

*Ammar Khammash: Notes on Formation, edited by Raafat Majzoub, is part of Dongola’s biannual book series. In 2022 and 2023, Dongola launched three projects: Zarathustra by Reza Abedini at Galerie Tanit in Beirut; Ambit magazine at Station in Beirut with British Council Lebanon; and DAS 01 at Darat Al Funun in Amman.