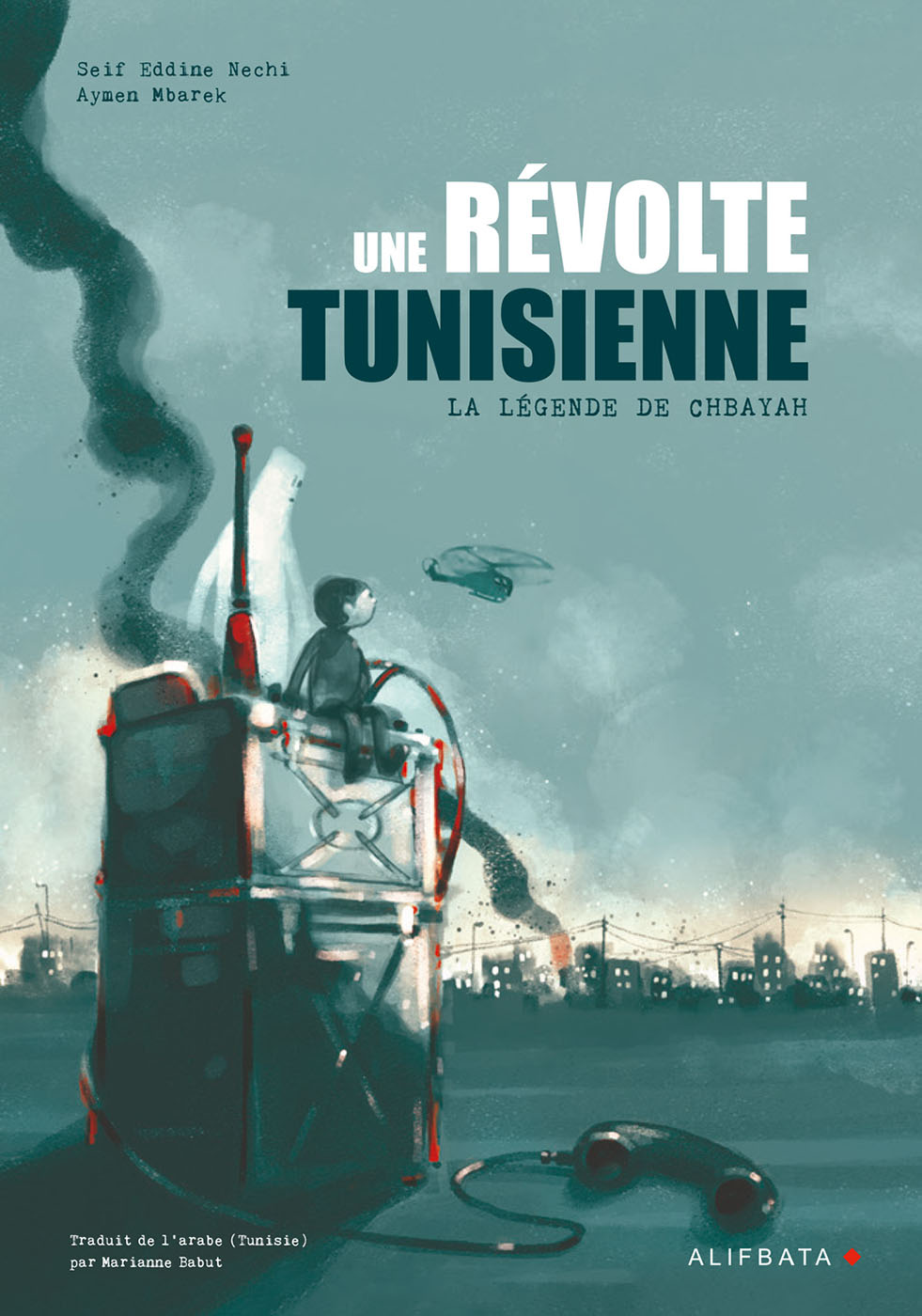

Released in January by Alifbata, Une Révolte Tunisienne, la légende de Chbayah (A Tunisian Revolt: The Legend of Chbayah) is a new graphic novel from Seif Eddine Nechi (illustrations) and Aymen Mbarek (text) At a time in Tunisia when both the left and the right are trying to reclaim the bread riots of 1984, the book stands out for its important historical and graphic research, intermingled with the authors’ personal memories. It reflects the wind of protest that has been blowing from Arab comics for over a decade.

Nada Ghosn

In 1984, the Tunisian people rise up following a government decision to increase the price of grain. An activist named Chbayah interferes in the uprising, sowing the seeds of discord among law enforcement by intercepting police communications, giving confusing counter-orders, and even by singing.

Interviewed for The Markaz Review, Seif Eddine Nechi explains, “I wanted to tell the little story of an unknown urban legend. We don’t know if Chbayah is still living among us or not, and that’s the funny thing. He appeared during riots to criticize police repression, and disappeared without anyone asking questions. Through this character, Aymen and I wanted to convey certain ideas about the insurgency, the eternal struggle between power and the oppressed people,” Eddine Nechi declared during a public event in Arles early in February, invited by the International College of Literary Translators, an association very committed to the translation of Arabic literature.

A memory of revolts

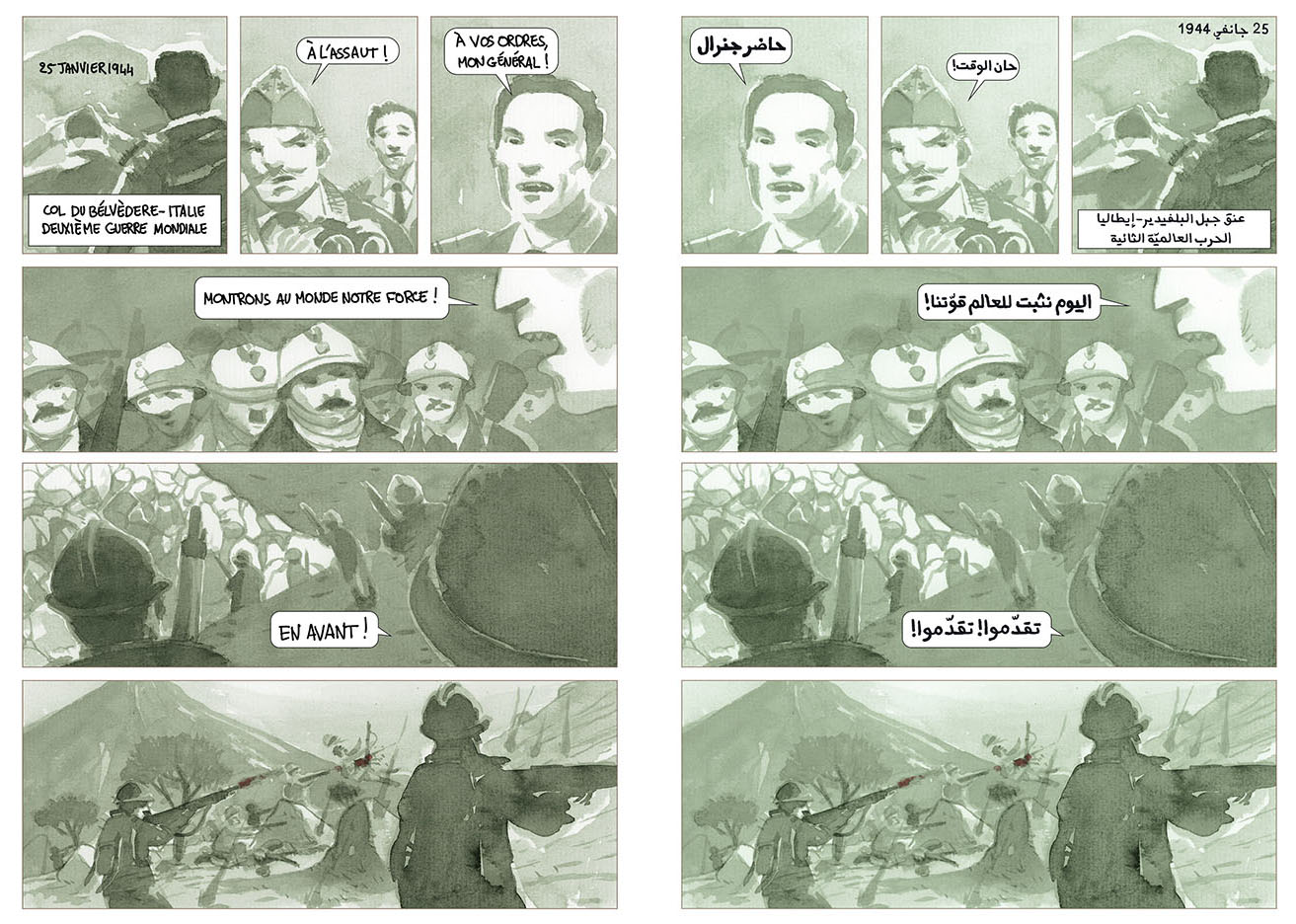

The book deals with the blurred, transformed, and doctored transmissions of history. The bread riots refer to earlier events: student union activism, the influence of Italian culture in modern history, and the fourth regiment of Tunisian riflemen during World War II — a third of whom fell in the ranks of the French expeditionary corps against Nazi Germany and the Italian fascists. These events are all recounted on the grandfather’s old radio. An allegory punctuates the events: a silent dialogue between a snake, a frog and a child.

“There are many forgotten stories, and it would be a shame not to make them known to everyone. I hope this work will lead to more research in the fields of history, sociology or psychology,” Eddine Nechi says. A child of the ‘70s, he experienced the transition of power from Bourguiba to Benali: “There was a general strike in 1978 that turned bad with many deaths and repression. It is a poorly known time in the history of modern Tunisia. Many people are unaware of the period of bread riots under Bourguiba that took place from December 27, 1983 to January 6, 1984. I wanted to convey what I experienced during this period, my fear of live ammunition, helicopters flying at low altitude, soldiers with machine guns, the dead in the streets, the deployment of the army, and the state of siege.”

For the comics author, insurrections are not new in Tunisia; what transpired during the Arab Spring had been brewing for decades. “The 1984 revolt motivated my outing on the streets on January 14, 2011,” he says. “But this time history must not repeat itself. Bourguiba’s government put an end to the bread riots by backtracking, and was applauded by the cheering crowd. Three years later, a putsch gave rise to a new undemocratic system, ” he points out.

The struggle for freedom

In 2008, Eddine Nechi attended the first International Festival of Comics in Algiers (FIBDA). At the time, he was working in advertising to earn a living. The sub-Saharan authors he discovered at FIBDA encouraged him to get serious about comics. “Realizing all the means I had at my disposal, I started a blog, then strips and mini-comics of socio-political criticism. Very quickly, the problem of censorship arose. My blog was banned in 2010, and that encouraged me to attack the system even more directly, such that I was censored again.”

Following the uprising of 2011, Seif Eddine Nechi joined the Tunisian collective Bande à BD, and he, Aymen Mbarek and others launched Lab619. Then the two comrades created Soubia, a website offering free access to comics. They landed a first award at the Cairo Comix festival for their fanzine, and the following year, they won the Mahmoud Kahil Award in Beirut. In 2018, the Comics initiative from Lebanon organized a big exhibition at the annual Festival Angoulême, such that the two graphic novelists found themselves on the international circuit, and started thinking about producing a book.

In order to reach a wider audience, they opted for literary Arabic, without staking out the sort of pan-Arabism that characterized the beginnings of the Arab graphic novel. “It is necessary to go beyond regionalism to go towards universal themes,” Eddine Nechi insists. “There are no studies on the market for comics in the Arab world, but many authors have given up, realizing the failures they faced. Even in Europe, they have a hard time making a living. Derivative products such as accessories help to make up for the shortcomings. A film made from a comic book is of course a springboard.”

Why COMIX? An Emerging Medium of Writing the Middle East and North Africa, by Aomar Boum

Rebellion Resurrected: The Will of Youth Against History, by George “Jad” Khoury

Publishing Arab comics, a challenge

Alifbata, the publisher of Une Révolte Tunisienne, sees its mission of making Arab comics known to the French readers as a commitment. The project was born out in 2017 of a desire to enrich the still very poor flow of Arabic translation in France. In an interview with TMR, Alifbata director Simona Gabrieli, noted that, “For me, comics are all the more interesting because they are able to reach a wide audience, to make accessible certain authors from the Arab world, and the view they have of society. No French publisher was interested in [Arab] comics. The first graphic novel to be translated from Arabic was Lena Merhej’s Mrabba wa Laban (Laban et Jam) in 2015.” [Editor’s note: The Syrian-French graphic novelist Riad Sattouf has been highly successful in France, and elsewhere, but writes in French, not Arabic.]

In fact, Alifbata launched in 2015 as a French nonprofit association with cross-cultural educational projects to promote Arab culture. Active in publishing since 2017, Alifbata now boasts 10 titles. Thanks to the support of France’s Centre National du Live et la Région, the publishing house now manages to work with major French broadcasters and media. “The Arab comic is still in its infancy, there is not a large production,” says Gabrieli. “The lack of specialized publishers does not encourage authors to embark on long albums. There are many short stories published in collections or fanzines. This format is quite risky in France because the collective book sells less. There is also a problem with distribution and most of the time the books travel in suitcases.”

If other publishers, such as Samandal in Lebanon or Al-Fan Al-Tessa in Egypt, are starting to publish graphic novels for adults, the Arab market remains emerging. This is why Alifbata, whose approach is part of a global ethic of support for authors, works on co-publications. Soubia, the publishing venture in Tunisia led by Seif Eddine Nechi and Aymen Mbarek, will publish this spring an Arabic version of their opus, which will allow them to print locally, and sell at prices adapted to the local market.