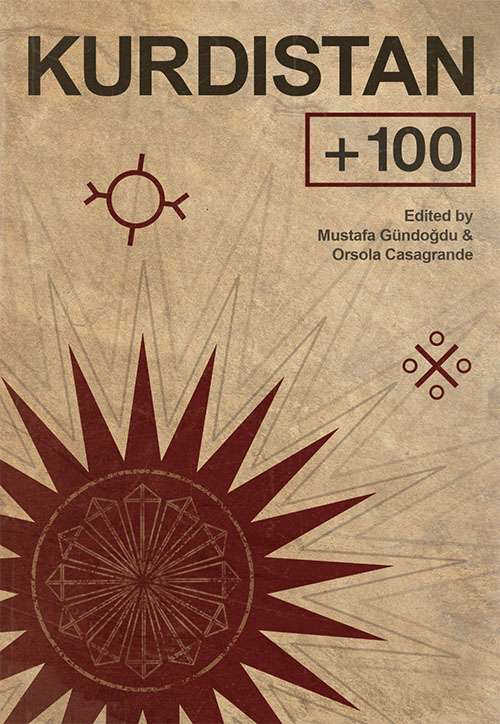

A book described as the first anthology of Kurdish science fiction ever collected and published in the UK offers a space for new expressions and new possibilities in the ongoing struggle for self-determination.

Kurdistan + 100: Stories from a Future State

Edited by Orsola Casagrande & Mustafa Gundogdu

Comma Press 2023

ISBN 9781912697366

Matt Broomfield

An author writes a science fiction story, in which members of her long-oppressed nation are trapped alive under a bombed-out mountain, form a microcosmic society, emerge in 2046 to lead a new liberatory political movement and achieve a brief flourishing of autonomy, only to be driven back under the mountain and slaughtered by fresh air-strikes. As a result of penning this and other, similar stories and poems, the writer is found guilty of terror offenses. When she tries to flee her country, the neighboring state refuses her entry and drives her back into the clutches of the authoritarian regime, which then cites the fact she attempted to flee as further proof of her guilt.

This extraordinary sequence of events is no meta-fictional exploration of censorship in a future dystopia, but the reality faced by Kurdish author Meral Şimşek. In their introduction to Kurdistan + 100 – Stories from a Future State, described as the first anthology of Kurdish science fiction ever collected and published in the UK, editors Orsola Casagrande and Mustafa Gündoğdu note that Turkish prosecutors are even citing the “utopian country” described Şimşek’s contribution as evidence of actual plans laid out by Kurdish militants.

This is despite the fact that Şimşek is careful to present the antagonizing power in her story as an un-named “Country X.” While the allegory is clear enough, prosecutors’ immediate assumption that Turkey is the country being referenced itself confirms the extent of nationalist paranoia under President Erdoğan’s brutal regime. Similarly, the way the editors represent Şimşek’s vision of all-too-brief, rapidly-quashed autonomy as a “utopia” suggests how severely repressed Kurdish dreams of independence remain.

Several contributors to the collection have been convicted and incarcerated for speaking out in support of Kurdish rights and identity, including leading Turkish Kurdish politician and author Selahattin Demirtaş, currently serving a 183-year sentence for peacefully advocating for his peoples’ rights. The collection as a whole is ultimately less speculative than it is burdened by the weight of historic violence and repression against the Kurdish people. Even when they emerge from their mountain retreat into futurity, Şimşek’s heroes live in traditional “wooden houses” since they are “nervous about living at altitude,” and “feel suffocated” by the “enormous skyscrapers” they behold. It’s a striking metaphor for the extent to which, for the Kurdish people, even an imagined future remains haunted by the past.

A fragmented resistance

Throughout the 20th century, Kurds have sought to imagine all manner of political alternatives to their current plight. Since the Middle East was divided up by imperial powers following WWI, the territory of Kurdistan remains divided between four states which have all consistently repressed the Kurdish identity: Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. Different efforts at establishing a better future for the Kurds have been inspired by very different ideas. In Iraq, the international reaction to Saddam Hussein’s genocide of the Kurds ultimately created space for the establishment of a Kurdish-nationalist devolved region, which itself stands accused of repressive, crony-capitalist rule by oil-rich elite Kurdish families. In neighboring Syrian Kurdistan, since 2011 the “Rojava revolution” has seen Kurds, Arabs and minorities attempt to implement a unique form of federal, direct-democratic, women-led governance, but the region remains internationally unrecognized, impoverished, and at the mercy of repeated Turkish assaults.

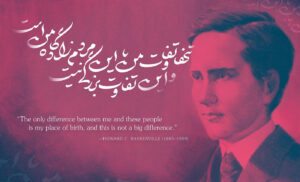

Contributors to Kurdistan +100 were asked to imagine what Kurdistan might look like in 2046, a century on from another landmark attempt at autonomy: the 1946 Republic of Mahabad, in Iranian Kurdistan. The Soviet-backed Republic survived less than a year, with the USSR offering little genuine protection before pulling out from the region under Western pressure, sealing the Kurds’ fate as forces controlled by Iran’s imperial Pahlavi dynasty retook control, burned Kurdish books, and executed Kurdish leader Qazi Mohammed and his allies.

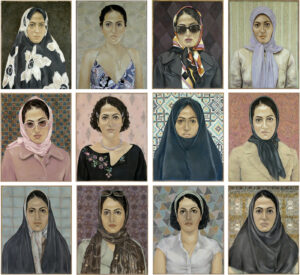

The Republic is well-known among Kurds as a heroic if doomed early effort in self-determination, but it is less commonly discussed in international settings, including those sympathetic to the Kurds. Even in Kurdish circles, Rojhilat (Iranian Kurdistan) tends to get the least airtime of those four divided regions. 2022’s major women-led uprisings in Iran, following the death of Kurdish woman Jina Mahsa Amini at the hands of Iran’s morality police, brought unprecedented global attention to the brutality endured by Iran’s Kurds from 1946 onward, but Jina’s Kurdish identity and the extent to which the protests were inspired by the Kurdish movement and the revolutionary principles embodied in the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” (“Women, Life, Freedom”) were often downplayed or ignored.

By basing their project around Mahabad, therefore, the editors make an important political choice. “The legacy of the Republic of Mahabad is still vivid in Kurdish cultural memory, not just for being the Kurds’ first modern experiment with self-rule, but also for the values it defended (equality, cultural tolerance, fraternity with the other peoples of the region and recognition of the Kurdish language),” they write in their introduction. Moreover, this decision makes it clear that the Kurdish national struggle did not emerge from nothing with the outbreak of war in Iraq and Syria, an increasingly-prominent role played by Kurdish forces in ISIS’ defeat, but has taken diverse, though interlinked, forms throughout history.

More broadly, the fragmented nature of the Kurdish national movement, which has taken Islamist and nakedly capitalist forms in some eras and regions while taking progressive, socialist and avowedly anti-capitalist form elsewhere, lends itself to exploration in the shape of a short story anthology. Here, contributors from all four regions of Kurdistan write in English, Turkish, as well as both Kurmanji and Sorani Kurdish. The history of Kurdish resistance is itself a patchwork of linked but distinct projects and ideologies, rather than a straightforward bildungsroman culminating in the neat conclusion of a nation-state.

Simple dys/utopias

Some individual contributions to the collection take a straightforward approach to speculative fiction, with the future serving as direct allegory for, or extension of, the present. Nariman Evdike’s “The Letter,” for example, is hardly sci-fi at all, rather expressing a simple, fundamental desire for an “independent state” and the protection of Kurdish and minority rights just like that being trialed in Evdike’s native Rojava today. Conversely, in “Friends Beyond the Mountains,” Ava Homa essentially retells the fall of Mahabad in a future setting — suggesting, perhaps, the “eternal return” of human suffering which Nietzsche once described as an endlessly tumbling hour-glass through which lives wash like grains of sand.

A contribution like Jîl Şwanî’s “The Wishing Star” is typical in heightening adverse circumstances already suffered by Kurds (water scarcity, isolation from the outside world, police repression) to dystopic levels. The grim, hardscrabble existence Şwanî envisages is familiar enough in its debt to other scorched-earth post-apocalyptic visions, and remarkable only in the sense that it reminds the Western reader that what might seem like sci-fi dystopia is close to lived reality elsewhere.

This does not necessarily mean, though, that the authors imagine crude dystopias or utopias, any more than the Kurds’ present reality is wholly defined by hope or despair alone. Contributors like Şimşek and Qadir Agid, in “The Last Hope,” are readily able to imagine future Kurdish infighting and betrayal despite apparent political gains. Şwanî’s story is redeemed by its knowing conclusion — after the journalist-protagonist escapes from the desertified wasteland of a post-apocalyptic Kurdish police-state hinterland and brings an account of the region’s devastation to the outside world, the story ends on a note of clear-eyed skepticism. “In the end, nothing changed,” laments the disillusioned journalist, having learned a lesson about the limits of advocacy and awareness-raising. Here, as elsewhere, normative, liberal narratives of progress are questioned by Kurdish authors who know their limitations full well.

Likewise, in Homa’s tale, an initially naive-seeming vision of a Kurdish utopia powered by progressive, Kurdish-programmed algorithms is ultimately undone in a reversal to very 20th-century forms of violence. To a people suffering under reactionary rule, straightforward development underwritten by supposedly-emancipatory technology isn’t an option: “the world beyond may have been technologically and scientifically progressing, but here, in my world, any breath could be my last.”

Towards the end of the book, suggestions for more radical forms of emancipation start to emerge. In “Cleaners of the World,” Hüseyin Karabey starts with the rather absurd premise of a Greta Thunberg stand-in and her Kurdish classmate traveling to the guerilla-filled mountains of Kurdistan to start a globalized, decentralized “Eco-Marxist” movement, a kind of Fridays-for-Future meets Kurdistan-Workers’-Party-on-Steroids. Karabey’s story is more a glorious mess of ideas than an effective sci-fi yarn, culminating in the take-down of the global fossil-fuel industry by a swarm of nanobots. (Thanks, Greta!)

Here, the implication is that the Kurds will need more radical solutions than mere progress and reform if they are to regain control of their future. Paradoxically, it’s this outré tale which may come closest to a realistic vision of the future, as Kurdish experiments in decentralized, community-based rule take on increasingly global relevance in an era of climate catastrophe, state collapse and resource competition. Likewise, Ömer Dilsoz closes his “Rises Like Water” with the radical implication that the Kurds’ very statelessness may, paradoxically, enable their liberation. In Dilsoz’s story, a Kurd is charged by NASA with passing through a wormhole into another world since they have no state government to defend them: by analogy, it might just be the fact that the Kurds are denied access to the nation-state form which ultimately leaves them open to more radical, world-altering alternatives.

Conversely, Muhammed Erbey’s “The Story Must Continue,” wherein the lost mayor of an independent Kurdish city flees to the mountains and is found hiding out in a shack with an “ordinary poor woman” who is revealed to be “extraordinary,” is marked by a political sense that liberation is found in the past, in the revitalization of long-severed bonds with the earth and the mountains, and the restoration of women’s lost, violently-suppressed knowledge.

Backward to the future

But this collection is not really about the future at all. In Agid’s “The Last Hope,” Qazi Muhammad, who led the Mahabad revolution, reappears in reincarnated form, “both dead and alive,” to judge the achievements of a heterotopic future Kurdish state. A zombified Kurdish martyr, whose body bears the scars of all the violence done to the Kurds from the vanquishing of Mahabad to the bloody war against ISIS to the equally grim fate of refugees in the Aegean, appears shambling at his own graveside. The past violently intrudes into all of these stories, laying claim to the future, preventing evolution and progression.

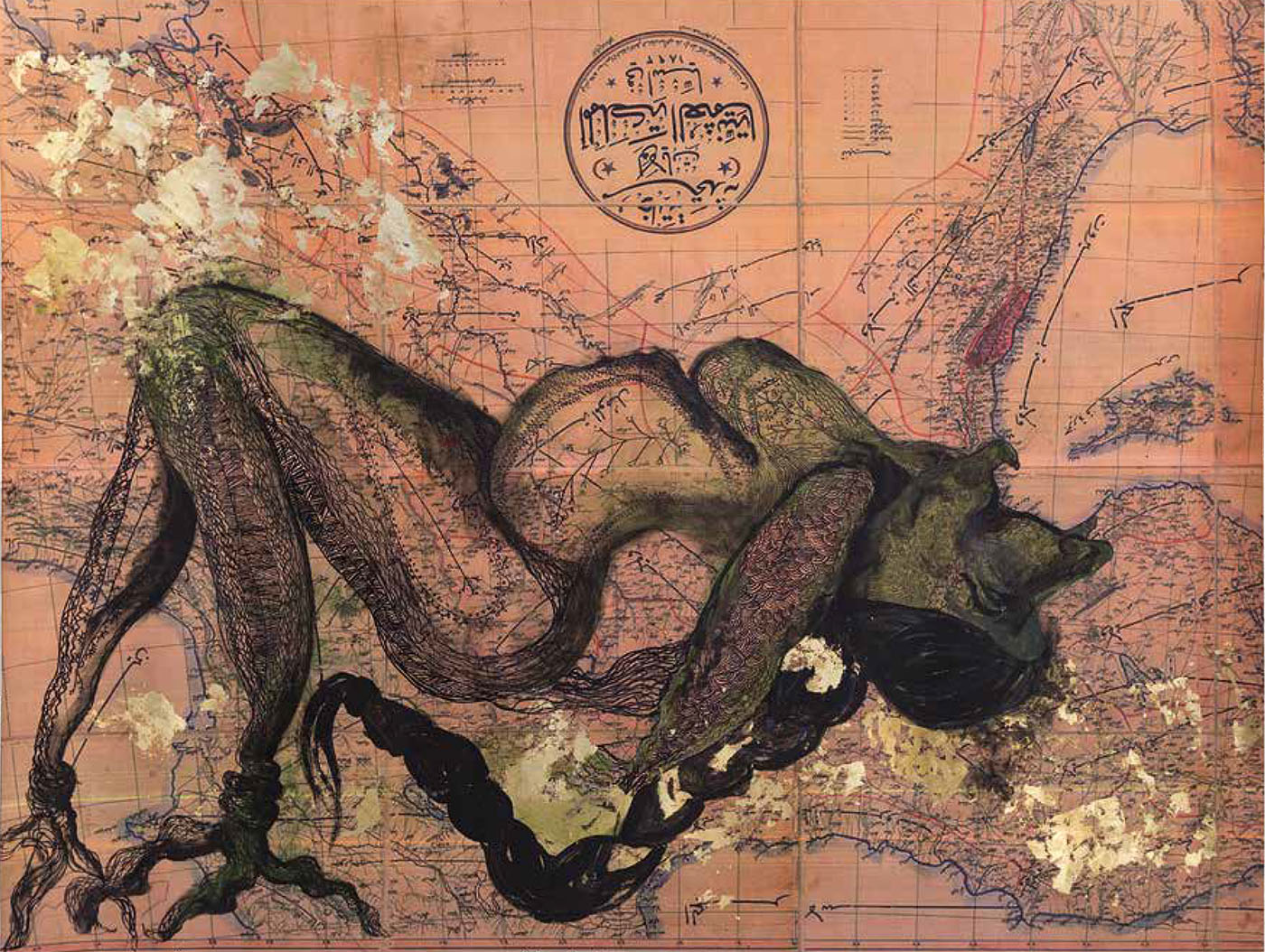

The stories here which stick longest in the memory are those in which memory itself is understood as an ambiguous, intoxicating quality. In Sema Kaygusuz’s “Waiting for the Leopard,” a contribution which more than any other evades direct political allegory to approach universal, existential concerns, the protagonist must choose between living with a “vacuous” avatar or a real, dangerous, damaged, living Kurdish woman, resurrected from the time of the Mahabad uprising. He is initially wary of speaking to his resurrected companion, since “every memory that might awaken meant a narrative, and every narrative meant a historical event.” But ultimately, he chooses the painful path of memory and recollection, thereby transforming from the passive “warden” of a vanished past to its active hunter — only for the resurrected past, his “chimeric sibling,” to turn upon him in the end. Even in its last sentence, Kaygusuz’s story is haunting, ambiguous, profound.

Like the hope left behind to humankind after Pandora opened her box, memory is at once our greatest blessing and our greatest curse. Hope stretches forward, memory backward, each therefore bringing with it the possibility of failure and defeat. Yet as humans, we must reckon with this reality. Perhaps, as in Jahangir Mahmoudveysi’s “Snuffed-out Candle,” we will end up trapped in our own “dirty, twisted book,” unable to escape into a more hopeful future. Perhaps, as in Şimşek’s story, we will end up back where we started from buried back beneath the mountain, with no way forward, and no way out of the past.

Regardless, as these authors know full well, and Kurdish political figurehead Abdullah Öcalan has powerfully argued, our present crisis is determined by our history. Before we can begin to speculate on what a truly alternative future might look like, we must first find ways to reckon with the past. Kurdistan +100 is a landmark step along the way.