Special correspondent in Algiers for "Le Monde Diplomatique," Pierre Daum, goes in search of Algerian artists in Algiers

It takes a good dose of courage, or despair, to live as an artist in Algiers. There are few places to show your work, state support is nearly non-existent, and there’s hardly anyone to buy what you produce. “The problem,” explains Ammar Bouras, “is that the objects I make now can’t be bought and hung on the wall because they’re pretty. No private individual wants to buy an installation that mixes video and photos. It is up to institutions to acquire it. But here in Algeria, state institutions can’t even manage to organize contemporary art exhibitions, much less buy works that are a little conceptual!”

Bouras was born two years after the independence of his country, and his face is exhausted. I meet him in his tiny studio, on the first floor of a building in Telemly, a neighborhood in central Algiers. The space, already narrow, is completely saturated with all kinds of objects, including books, paintings, huge photos, coffee cups and old cameras. Last June, Bouras was invited to the 12th Berlin Biennale by its curator, Kader Attia, a French artist born into an Algerian family in the suburbs of Paris. Having quickly spent the 4,000 euros Bouras received for the production of the work going into the show, a friend bought him at plane ticket so that he could go to the Biennale’s opening.

When he begins to tell me about “24°3′55″N 5°3′23’E,” the work he exhibited there, his face finally lights up. It is an installation composed of photographic collages and a video. “I went to the great Algerian south, in the Hoggar massif, at the very place of the nuclear explosion that the French government caused in May 1962, two months before Algeria’s independence.” [From 1960-1966, the French military set off 13 nuclear tests in the Algeria Sahara region. ED]

The place and its inhabitants were devastated, to general indifference, and the artist wanted to show how much this silence persists, as much in France as in Algeria. And he is surprised that no Algerian institution is thinking of acquiring this work? When one knows the animosity of the Algerian authorities against any critical discourse towards them, one can hardly imagine an official of the Ministry of Culture taking the risk of losing his job for such an installation.

Bouras resumes his gruff air: “I am not against receiving money from the state, since it comes out of my taxes, but if it is then to be forced to cozy up to them, then no.” Even if it means starving? Yes, even if it means starving. To earn a living, and poorly at that, Bouras has always worked as a press photographer — publishing a beautiful book of his photographs taken during the civil war, entitled 1990-1995, Algérie, chronique photographique (Barzakh Editions, Algiers, 2018), with a preface by the historian Malika Rahal. He explains: “But at El Watan, the newspaper where I’ve worked the last ten years, we are on strike, because we have not been paid since March 2022!” Before I head out, the artist adds in a calm voice, “I live an extraordinary revolt against this country. What I am experiencing is a reflection of Algeria. The masses are having a much harder time getting by than before.”

I leave my encounter with Bouras having a rather desperate first impression of the Algerian art scene. However, during the next few days that I spent wandering around the city center in search of places and artists, I finally discovered that there is in Algiers an extraordinarily lively contemporary art scene, full of talent and inventiveness, some of whose names, moreover, already appear in fairs and major international exhibitions.

Algerian artists in Algiers

A word to the wise: in this story, I am not talking about Algerian artists who have become world stars like Adel Abdessemed, Rachid Koraïchi, Zineb Sedira, Hamza Bounoua or Zoulikha Bouabdellah, and who have long since left their native land. No, I’m talking about artists who actually live in Algeria, in Algiers, and whose work is nourished by their Algerian culture —who each day, like Ammar Bouras, have to face a life that isn’t easy.

The list of visual artists to be counted today is not very long, even if I forget a few names (taking inventory is always perilous, at the risk of earning some hostility from those unmentioned): Bardi (real name Mehdi Djelil, born 1985), Ammar Bouras (1964), Fatima Chafaa (1973), Rima Djahnine (1979), El Maya (real name Maya Benchikh El Fegoun, 1988), Mourad Krinah (1980), Nawel Louerrad (1981), Amina Menia (1976), Lydia Ourahmane (1992), Fethi Sahraoui (1993), Abdo Shanan (1982), Fella Tamzali (1971), Hellal Zoubir (1952), and Sofiane Zouggar (1982). We could add some artists from the provinces, like Yasser Ameur in Mostaganem, Lounis Baouche in Bejaia (1995), Aya Bennacer in Batna (1997), and Sadek Rahim in Oran (1971). Most of these artists were shown in the beautiful exhibition “Waiting for Omar Gatlato.” organized in the spring of 2021, at the Friche de la Belle de Mai, in Marseille, by the curator Natasha Marie Llorens.

Are these names known in Algeria? Not really…Not that it is difficult to be a prophet in one’s own country, but for Algeria, the only way to survive is to access the international network of artist residencies, fairs and exhibitions. “The most interesting Algerian artists are totally unknown here!” opines designer Feriel Gasmi, who knows the Algerian art scene like the back of her hand. “They survive thanks to their international network,” she says, at the risk — or the luck? — of getting caught up in this outside world, and eventually moving to Paris, Berlin or London. As for those who stay, another risk weighs on their shoulders, which Gasmi is quick to point out: “A sort of more or less expressed injunction to work on post-colonial subjects.”

Essentially, if you want to please people “over there,” on the other side of the Mediterranean, there are three or four subjects that work very well: the wounds of colonization, the place of women, the weight of traditions (and in particular of Islam), and the absence of democracy. By the way, which institution in Algeria offers the most money to young Algerian artists? The French Institute of Algeria (IFA), which every year offers grants of up to 10,000 euros for creating artwork — a fabulous sum for an artist living in Algeria.

These constraints, the result of a relationship still in tension between Algeria and France, do not prevent the emergence of absolutely fascinating artistic careers. Amina Menia’s is certainly one of the best examples. A sort of archaeologist of her city, she uses all manner of techniques (installations, photographs, videos, performances, etc.) to bring to light the sediments that history has deposited there, and to try to reappropriate spaces forbidden by a power as obscure as it is authoritarian.

“I don’t have enough money to afford a studio. So, I decided that all of Algiers would be my studio,” she says.

Menia was born in this light-filled Mediterranean capital in 1976. She studied for five years in the city’s beautiful École des Beaux-Arts, a school that is more than a century old. It was a place of great effervescence in the years following independence, but today it suffers from a form of somnolence. When she left, the young artist was overflowing with projects. Her goal was to reappropriate confiscated spaces, and access the margins of the city. “I had imagined a vast cycle of urban installations, in four chapters, with sound routes in the construction sites of the subway, or in the Essai Garden. But I never got the authorizations! The project finally turned into an archive.”

Menia continues a very conceptual artistic practice, based on documentation, which she photographs and stages in superb installations. Hers is a practice that appeals in the west, where her works have been shown in prestigious venues including the Palais de Tokyo (Paris), Cleveland Museum of Art (USA), the Royal Hibernian Academy (Dublin), the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of African Design (Johannesburg), and the Mucem in Marseille. More recently, she participated in MANIFESTA 2020, the European biennial of contemporary creation held that year in Marseille.

However, her prestigious list of exhibitions shouldn’t hide the reality. “The reality is that it is very difficult for us to obtain a visa,” she confides to me in the small tearoom where she agreed to meet me, off the rue Didouche Mourad (hereafter simply the rue Didouche). “And therefore, it’s difficult to travel, to exhibit, and to encounter others.” I ask her what are the places in Algeria where she can show her work? “None,” she says in a desperate tone. The invitations come mainly from abroad. And then she picks herself up. “No, I am unfair. Six months ago, I was lucky enough to have a 10-day solo exhibition at Ateliers Sauvages.”

Ateliers Sauvages

It is impossible to talk about the Algerian contemporary art scene without mentioning a unique spot, a huge private exhibition space, located on the ground floor of 38 rue Didouche, in one of those sumptuous Haussmann buildings built “in the time of France,” and which contribute to the unique character of downtown Algiers. These Ateliers Sauvages (wild workshops) are located a few dozen meters from the tearoom where we converse. The space, through which a large part of the Algerian avant-garde has already passed, exists thanks to the will and the financial ease of a woman named Wassyla Tamzali, a key figure in the Parisian-Algerian intelligentsia.

At the age of 81, this intellectual, author and activist has had several lives, woven around two guiding principles: feminism and her country of origin. Lawyer, former director of women’s rights at UNESCO in Paris, political activist, writer, exhibition curator, organizer of major cultural events, Wassyla Tamzali has been living in the French capital for a very long time, while continuing to travel around the world, going from conferences to militant meetings for women’s rights. Born into a wealthy family from Béjaïa — I am talking about her father’s side of the family, her mother being a Spanish pied-noire — she has kept several properties in Algeria, including a very beautiful apartment located at the end of the rue Didouche, really the main artery of central Algiers, lined with large white buildings with blue shutters, built at the time of colonization on the model of Parisian buildings.

In 2015, Tamzali bought the former warehouse of the Coca-Cola factory in Algiers, a stone’s throw from her home, and decided to make it instrumental in supporting the Algerian art scene. At the time, she had been interested in young visual artists for several years, as a result of her niece Fella Tamzali, herself a painter and former student of the École des Beaux-Arts, having introduced her to the scene. For the renovation of the Ateliers Sauvages’ 500 square meters of bricks and metal beams, Wassyla Tamzali called on the designer Feriel Gasmi.

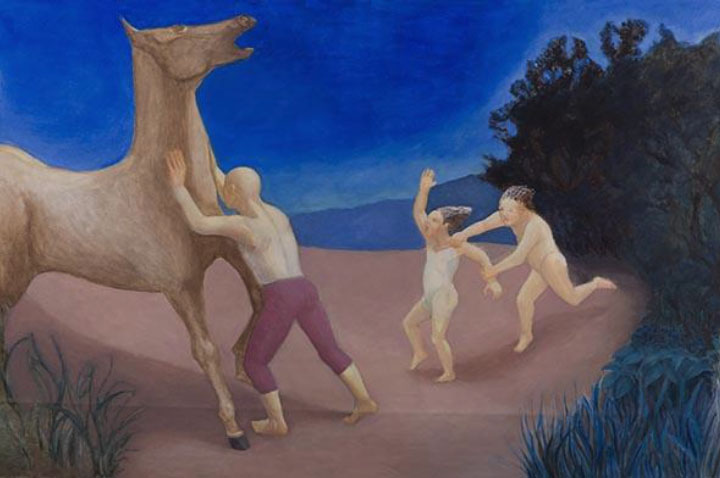

When I go there two days later, to visit the place that I discover has been deserted since Amina Menia’s exhibition, I come across a small woman, whose body appears all the more diminutive in contrast to the gigantic volume occupied by the former American beverage warehouse. She is concentrated on the two paintings she’s working on simultaneously — one representing a child wearing a strange mask surrounded by two dogs, the other an adult hunter followed by a (third) dog. Since the space is really for her, Fella Tamzali does not seem at all crushed by the immensity of the “workshop,” as she has the key to the Ateliers Sauvages and comes to work here every morning. On the contrary, the artist exudes a quiet strength, perhaps falsely at peace behind a stern face that evokes the severity of a Frida Kahlo, even when it lights up with a sudden burst of laughter. Her work reflects this ambivalence: large canvases representing men, women (especially) and children, sketched in pure lines, in flat pastels, always caught in particular actions: one washes her hair, another mops the floor, a man rides a horse, a woman taps an octopus on the ground to soften it…

“My painting results from mental images generated spontaneously from my life experiences,” explains the artist, “which I combine with images gleaned at random — provided, however, that they can resonate with the ones I’ve imagined. I stage human and animal figures, placed in selected locations. The term ‘staging’ is important to me, because I try to make all the elements of the painting work together to express a certain emotion.”

But behind these seemingly innocuous scenes there are hidden tensions, or pent-up suffering. “In the work of Fella Tamzali,” writes the Canadian critic and documentary filmmaker Hejer Charf, who knows the Algerian scene well, “the wound and the fright appear to the eye in a muted way, in the off-screen of the flat light, the clarity of the colors and the fading strength. A pastel atmosphere, a refined texture, a muted whiteness, fault lines sketching a robust outline, pale bodies bending under the weight of silence and torment.”

Tamzali’s disturbing works have been shown in Dakar, Beirut, Montreal, New York, Copenhagen, etc.

I leave the artist to her two canvases in her immense solitary studio, to find the noisy sidewalk of the rue Didouche. I was told about three other interesting places of Algerian contemporary art: Artissimo (28 rue Didouche) and Rhizome (82 rue Didouche). These three places are also located on the southern end of the street, which clearly appears to me as the markaz (the center) of Algerian contemporary art. Each of the three is installed in a large bourgeois apartment converted into offices, exhibition room, kitchen and artist’s room. The first two mix art school with exhibition and conference space, in a hybrid format that took me a while to understand.

Rhizome presents itself as a more classic gallery, opened in 2020 by a young entrepreneurial couple. “Our goal is to lay the foundations of an ecosystem of contemporary art in Algeria,” explains the 30-year-old director, Khaled Bouzidi, handing me his card. And Myriam Amroun, the artistic director, also 30, adds: “We are very present internationally. We were at Paris International 2021 and 2022, at Art Dubai in March 2022, and at the Basel fair in June 2022.” I don’t dare ask them too much, for fear of getting on their nerves (in case they relied on their parents), for instance, where they found the initial investment to launch their business. A painting by Lounis Baouche, the young 27-year-old artist they presented in Basel, probably wouldn’t cost a buyer more than 500 euros, of which they must pay at least half to the artist. As for the rent of their apartment-gallery, it can easily run them 10 000 € per year. “We don’t ask for any subsidy from the state, to remain independent,” they say.

Zafira Ouartsi, the founder of Artissimo, has no problem making rent: she created her art school about 20 years ago in the apartment where she grew up, which her father kindly bequeathed to her. In her early fifties, Ouartsi is full of new ideas, always curious to discover fresh talent. Her project seems a bit all over the place (school? artistic hub? cultural scene?), but one meets a diverse range of friendly and often talented artists, who perform in her father’s old living room, emptied of its furniture and repainted in white.

I am told about one last place as being certainly the most interesting. I try to contact the person in charge, who ends up telling me by email that he does not want his project to appear in my article. “It would put us in too much danger.”

It is not the first time that I come across Algerians worried about appearing in the media, so I do not insist.

After this small tour of the apartment-galleries of the rue Didouche, I say to myself that decidedly, these few places where one can see contemporary art in Algiers cut a poor figure when compared to the Ateliers Sauvages. The only place that could compare with the former Coca-Cola warehouse is the Museum of Modern Art of Algiers (MoMAA), which opened in 2007 in the former Galeries de France, a magnificent neo-Moorish building located further down, behind the old post office. With a real acquisition policy at the beginning, when Khalida Toumi was Minister of Culture, it had marked a spectacular upheaval in the history of Algerian contemporary art. The authorities allowed it to decline, then closed it with advent of Covid, without ever reopening it. “Closed for Repairs” is posted on the front entrance, which can be translated in Algeria by sine die. As for Khalida Toumi, she found herself in prison at the time of the Hirak, the gigantic popular uprising that shook the government in 2019, for “squandering public money, abuse of office and granting undue benefits to others,” according to El Watan. She is now on parole. And the Hirak is in a prolonged coma.

My artistic peregrinations in the center of Algiers are coming to an end, and a realization comes to mind, like a sudden truth: all these actors of the Algerian scene that I met — artists, persons in charge of exhibition spaces, cultural impresarios, all speak in perfect French, without the slightest accent. The art they present is shown in France and in some other European countries. Where are those who, like 95% of the Algerian population (a figure that I have established with a wet finger, after dozens of stays in this country), do not speak French, or very badly, or in any case with an accent?

I remember that Feriel Gasmi told me about Hamza Bounoua (born in 1979), who has nearly 20,000 followers on Instagram:

“He has managed to escape this toxic relationship with France: he shares his life between Dubai and Malmö, in Sweden, and his art is part of the Arab tradition of calligraphy, revised in an extremely modern, even conceptual way.” A sort of male and Arabic-speaking counterpart to Wassyla Tamzali, but less wealthy, Hamza Bounoua opened Diwaniya, a contemporary art gallery in Algiers, in 2020, whose goal is, according to his Facebook page, is “to ensure access to contemporary Arab-Islamic art to a wider audience and to introduce innovative talent in Arab-Islamic art recognized internationally in Algeria.”

As this visit to Algiers is wrapping up, I unfortunately don’t have the time to go and see Diwaniya, located in the district of Chéraga, far from the city center and from the rue Didouche, where the (French-speaking) contemporary art scene is concentrated. Back in France, though, I came across a revealing interview that Hamza Bounoua gave in March 2020 to El Watan:

“Unlike other galleries,” he explained, “our vision is to promote Arab-Islamic art on an international scale, and to foster the image of this art abroad. An art crossed with Andalusian, North African, Berber and Ottoman influence We hope to be a new era for MENA art in Algiers.” I tell myself that next time, this is where I must go.