Research into the iconic fashion designs of Mehremonir Jahanbani led a contemporary artist to the farthest corners of Iran.

Bibi Manavi

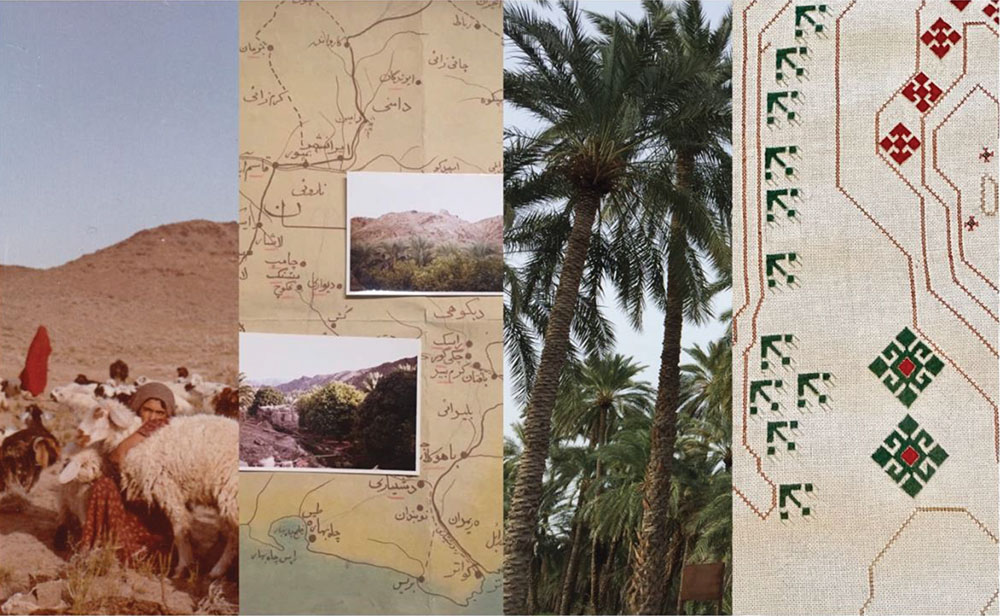

The plane from Tehran to Iran’s southeast border flew at a low altitude over a panoramic view of the vast plateau with its dunes and mountainous terrain, a palette of bruised colors and scattered patches of green. After landing, I embarked on a five-hour, off-road adventure through Baluchestan’s ruggedly arid landscape to the oasis area of Irandeghan.

In the fierce sun, the tall date trees stood with their leaves gently sweeping in the wind. Their trunks were gnarled with age and time, their sweet fruits a sublime gift. The trees and sand are a testament to the power of the land and fortitude of the people who call this place home.

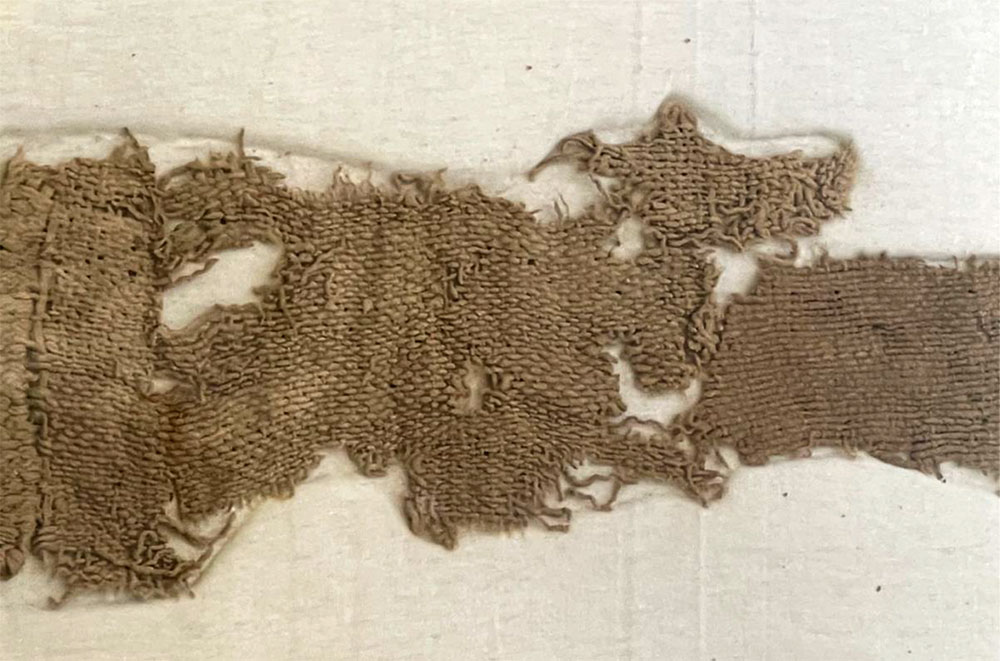

The province of Sistan and Baluchestan is rich in history, culture and folklore. However, due to the region’s harsh climate and geographical coordinates as a remote border territory, it has largely remained in the shadows of obscurity. Still, archeological excavations scattered across the province have revealed the remains of what was once a great civilization, which settled below the barchan dunes of Gholaman, or the 5,000-years-old “Burt City” where some of the oldest pieces of textile in the world have been found.

Textiles and threads — specifically a traditional embroidery — brought me to Baluchestan, first in 2018. I was following in the footsteps of the influential textile designer Mehremonir “Nini” Jahanbani. Her discovery and adaptation of a cultural heritage elevated the then little-known Baluchi embroidery to the heights of haute couture worn by an empress in the 1960s and 1970s. Today, this embroidery is in the mainstream of fashion as an emblem of authentic, artful craft.

The embroidered dresses and gowns belonging to Empress Farah Pahlavi are kept in palaces in Tehran that have become museums. However, when I went to see the iconic gowns Nini made with couturist Pari Zolfaghari and designer Keyvan Khosrovani, I found the gowns displayed under someone else’s name. With the help of Nini’s daughter, Sheitaneh, I searched for stories that had been buried for forty years.

Nini was the daughter of Amanollah Mirza Jahanbabni (1895–1974), the general under Reza Shah Pahlavi (1878–1944) responsible for finalizing the border negotiations between Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. It was after accompanying her father on one of his trips to the region that she began her four-decade long love affair with Baluchestan. She learned its arts, language and traditional customs. In Irandeghan she worked with women embroiderers to deconstruct their intricate traditional patterns. Their ancient palette of five colors with which the women embroidered was expanded to nearly 300. Under Nini’s tutelage a modern design aesthetic was created.

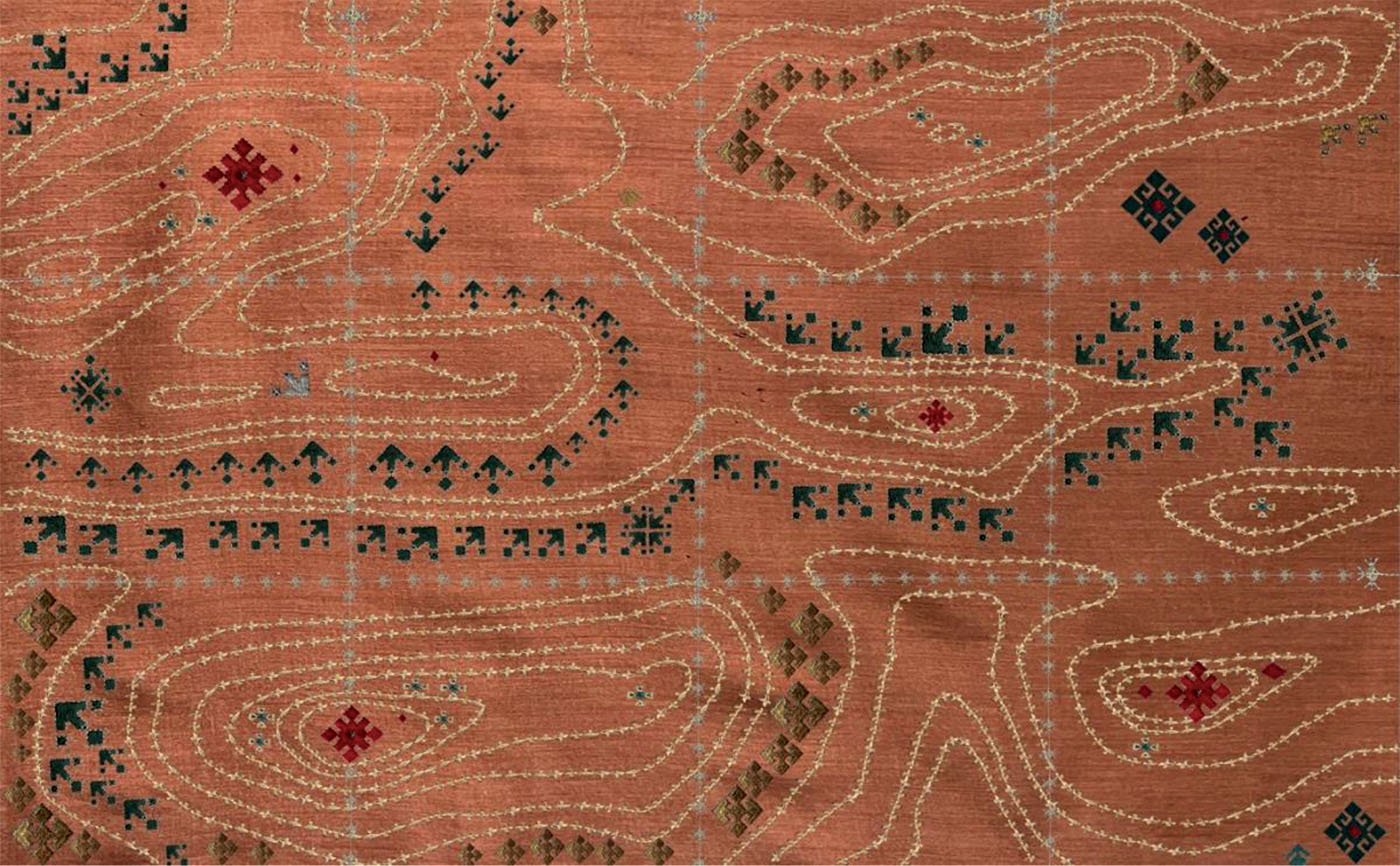

When I first started my research into Nini’s life I was presented with boxes pertaining to her work and life. I spent the next two years cutting and pasting to find out where Nini went and what she did. Maps were invaluable; they allowed me to understand the corners of Baluchestan Nini had traveled to. My father is an architect and I am no stranger to topography and topographical maps. When I went to Baluchestan, the women embroiderers asked me where I was from, and I pulled out my book of maps. I showed them not only my own travels but where they and their villages were situated in the country and their placement in the wider world.

During that first visit, I had the privilege of meeting the women Nini had collaborated with, as well as their daughters and granddaughters. I expressed my desire to return one day and collaborate with these women who held the treasures of their craft at their fingertips.

The land where they lived had also enthralled me, and after that first trip I dedicated years to researching the region’s rich embroidery tradition, its topography and flora. In 2022, I finally carved out a path to work with the new generation of women embroiders in Irandeghan. The first designs I made were the result of countless hours pouring over maps and zooming in and out on Google Maps to identify the villages where these artisans lived.

It was only natural for me — almost an unconscious decision on my part — to gravitate towards designs inspired by mountains. I felt an intrinsic connection with those spaces, the elevations and peaks that had guided my early journeys. Those initial explorations had become an integral part of my creative process. I fused my passion for landscape, design and topographic maps with Baluchi embroidery, and together with the women of Irandeghan, we embarked on the journey of “Stitching Baluchestan.”

My intention is to re-establish the pristine embroidery on the cultural map and this could only be accomplished with the women’s active participation. However, the actual realization was more complex than I had initially envisioned. Baluchestan is still in turmoil and navigating it posed many challenges. With limited internet connectivity, unreliable telephone services and generally difficult access, I find myself reaching out to individuals in other villages to relay my messages to the women embroiderers.

Now, half a century has passed since Nini’s pioneering efforts, and the region remains largely unchanged — remote and obscure.