Baraa and Zaman: Reading Egyptian Modernity in Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Mummy , by Youssef Rakha

Palgrave 2020

ISBN 9783030613532

Sherifa Zuhur

Baraa and Zaman: Reading Egyptian Modernity in Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Mummy by Youssef Rakha is a surprising book, constructed as a series of separate paragraphs, like prose haiku. The author calls our attention to the 1969 film, which like other productions of Egypt’s golden age of cinema, 1940s-1960s, interroga

tes the country’s identity. Thus, an adventure into cinematic history provides a methodology for interpreting Egypt and its internal and external relationships, and sheds light on Egypt’s trajectory.

Rakha is the author of The Book of the Sultan’s Seal: Strange Incidents from History in the City of Mars (Kitab at-Tugra: Gharaib at-Tarikh fi Madinat al-Marrikh, Cairo: Dar Al-Shorouk, 2011) which has been translated to English and French, and other novels, essays, and poems. His lengthy experience as a culturally-oriented journalist, editor, and photographer/writer, as well as his introductions of other important younger poets, writers and cultural figures on his website, sultansseal.com, position him in the current Egyptian scene. He is part of a generation of Egyptian writers who often explore topics through a personal and historical lens. In this new work, he, like The Mummy, invokes the past, zaman (an age) as a key principle, relying on legacy and authenticity. Contrasting this, we learn of a contrasting condition, baraa, (literally, outside, barra in my transliteration) — externality, colonialism, neocolonialism, and perhaps even Occidentalism.

The barra-first rule in Egypt is that one must attain recognition, fame or success in the outside world, to matter, or to have influence. One needs a foreign language education. One must publish in foreign languages and foreign contacts are useful. Opera singers and actors should gain renown abroad. Rakha also explains that the ideas of the Arab Spring were barra-derived at the expense of the local. (69) Barra-oriented personages important to the ill-fated January 25th Revolution were the Godfather of the Revolution, Mohamed El Baradei and comedian Bassem Yousef, both of whom had, ironically, to escape barra (from Egypt).

Egypt’s modernity goes back to struggles between Egypt’s rulers and foreign powers. The exploits and achievements of Khedive Isma’il Pasha (1830 – 1895), the grandson of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha who modernized Cairo, and enabled the construction of the Suez canal, and 8,000 miles of irrigation canals, as well as thousands of miles of railroads, telegraph lines, 400 bridges, and 4,500 schools, exemplified a barra-orientation which justified Egypt’s use of European models, and designs. In these efforts, Khedive Isma’il accrued enormous debts leading to his downfall, British military seizure of Egypt and to Isma’il’s exile. All this is significant as The Mummy is set in the year 1881.

In this period, the archaeological collection at Azbakiyya was handed over to the Archduke Maximillian of Austria, and ended up in Vienna. So too, at the outset of the film The Mummy, French Egyptologist, Gaston Camille Maspero who can translate Egyptian hieroglyphics is juxtaposed to Ahmed Effendi, the young Egyptian Egyptologist. Both of these men — Westerner and Egyptian — have pharaohphilia (love of the pharaohs) at the heart of their pursuit of zaman, here representing antiquity, authenticity and tradition. “Egyptology turned Egyptianness into an object of European scrutiny, also avarice, marginalizing (indeed criminalizing some Egyptians) but also a hitherto nonexistent subject for a collective sense of self” writes Rakha (73).

Italian filmmaker Roberto Rosselini’s discovery of Shadi’s script helped to propel the film’s creation. “Just as ancient Egypt cannot exist without European intervention, so Shadi’s career cannot kick off until an Italian approaches the Egyptian state,” (68) because of the barra-first principle. In this way, the Muslim Brotherhood’s so-called ‘moderate Islam’ gained traction through American think tanks (barra) and Mohammed ElBaradei gaining fame by succeeding Hans Blix in the IAEA, Bassem Youssef by being called the “Egyptian Jon Stewart,” or the late feminist Nawal El Saadawi being labeled the “Egyptian Simone de Beauvoir.” These unequal cultural valuations, considered barra as compliments, grate domestically.

Can one read the book without having viewed The Mummy? Baraa and Zaman is worth reading without having seen the film, though it will speak more distinctly to those with some, or a good deal of background knowledge of Egypt. Rakha is not merely rendering an homage to The Mummy; he recognizes that it is fascinating without being a very good film, and irreverently asks why? As the story of the discovery of a cache of mummies by the Abd al-Rasul gang, the film addresses greed, and the past and present theme of corruption. Rakha points out the illogic in the script — that the younger generation would be so revolted by the desecration of tombs that they would risk their lives and give up their family legacy (44). This isn’t merely a lack of logic, it centers morality in modernity, as if the younger generation would, through sheer will, break with the past, and, therefore be cursed by the Mother, the Lady of the House.

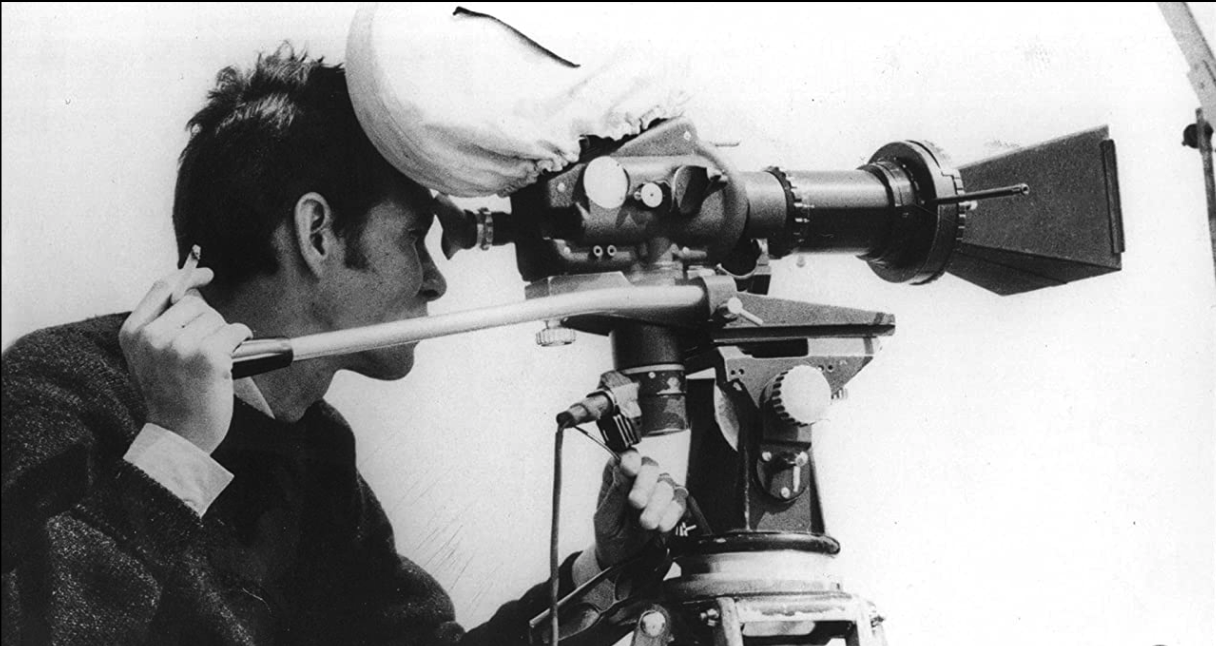

Rakha explores the nationalism and near deification of Gamal abd al-Nasser involved in the making of this film, explaining Salah Jahine’s (poet, lyricist cartoonist, editor) “pathological relationship to Nasser,” an extreme patriotism actualized in songs of that era, including those by composer Kamal al-Tawil with Jahine and sung by Abd al-Halim Hafez. Egypt’s golden age of cinema included singer/actor Soad Hosny (1942–2001), superstar comedian Adel Imam (b. 1940) and Shadi Abdel Salam, who eventually made The Mummy — a graduate of Victoria College, an architect and aspiring filmmaker who apprenticed himself to filmmaker, Salah Abu Seif. In many ways Abdel Salam was like filmmaker Youssef Chahine, but his roots were in Upper Egypt. Abdel Salam told an interviewer in 1975 that he was inspired in Mallawi, his mother’s town in Minya, to investigate “the meaning and the life of being Egyptian…” (40). Rakha also explains how the Naksa, Egypt’s defeat by Israel in 1967, powerfully impacted Abdel Salam who admitted that the film might be his way of asserting both Egypt’s continuity and the pain of its decline. Rakha associates the grieving at the opening and ending of the film, at the death of the patriarch, celebrated in rural Egypt with the firing of weapons, with the grief for Egypt-the-father or Egypt’s father (Nasser) in the Naksa. (47)

Rakha describes the visual beauty of the film, and its odd and unexplained symbolism, as that of the eye — the Eye of Horus, and the viewer’s eye gazing at the film’s spectacle, “seeing past aesthetics into history.” (51) Rakha reminds us of the popularity of ancient Egyptian themes in literature, as in Naguib Mahfouz’ first three novels, and in Tawfiq al-Hakim’s quest for revival and an ‘idol’ in his 1933 novel, Return of the Spirit, each volume of which begins with citations from the Book of the Dead.

Of the many other meaningful insights in this book, among them the mummy portraits fulfilling their function of providing eternal life, I enjoyed Rakha’s discussion of the mawawil, the often lamenting, vocal improvisations on folk texts. He connects the deep emotionalism of the mawwal to the mortuary tradition in upper Egypt. In one mawwal from Minya, a singer implores the boat’s captain to carry him to the West Bank of the Nile, where he can meet his deceased loved ones. This example of an ancient tradition living on in folk music is Rakha’s insight, not The Mummy’s, but it’s emblematic of the film’s goals. Whilst riling against taboo breakers, the discovery of the mummies was a “resurrection spell,” and also a national liberation slogan” (94) that Rakha claims for modern Egypt.

The authenticity vs. modernity dynamic that I myself encountered in my twenties in Cairo, was a more primitive version of the baraa-zaman polarity. It was always framed from barra — on the edifices created by Western scholars. Rakha writes, “It is not as if you can choose to relinquish modernity however attached to tradition you might be. But it is not as if you can forget that, rather than growing out of it or being organically grafted onto it, modernity was suddenly imposed on your history, overtaking your sense of self in demeaning ways.” (89)

The story of The Mummy, then, is perhaps not what director Shadi Abdel Salam intended to tell, but with Rakha’s examination, its underlying truth emerges. It seems that an Egyptian, like Rakha, may indirectly address equality, justice and freedom (the goals of the January 25th revolution) and focus on the barra-zaman dialectic (103) at present, in order to perceive the likely future.