A free man, Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar now lives in Sweden.

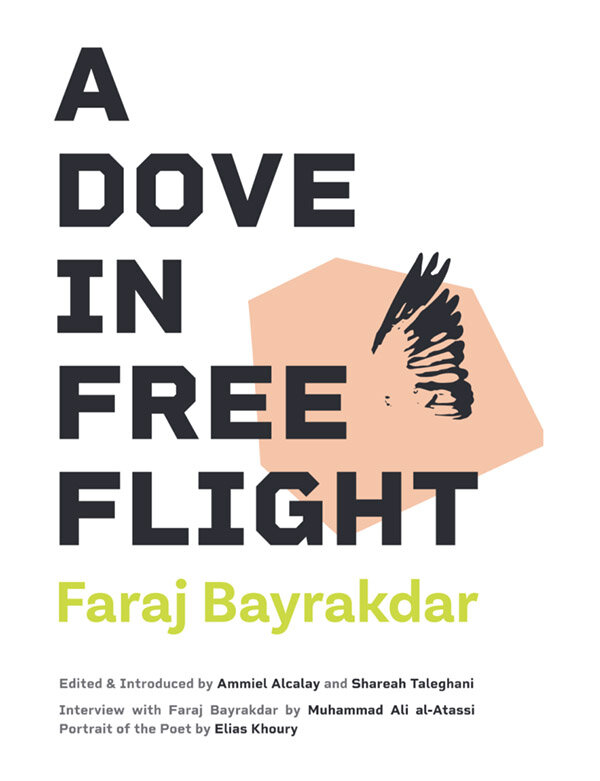

A Dove in Free Flight, editors Ammiel Alcalay and Shareah Taleghani

Upset Press 2021

ISBN 9781937357009

After he survived 14 years in Syria’s nightmarish prison system, poet Faraj Bayrakdar told an interviewer, “Prison is extreme predatory masculinity. Freedom is extreme merciful femininity. I cannot express the symbolism of prison and its whips in more than these words.” Now, 18 years in the making, comes Bayrakdar’s A Dove in Free Flight from Upset Press, edited and introduced by Ammiel Alcalay and Shareah Taleghani with a preface by Elias Khoury. These searing poems, written in prison on cigarette paper and smuggled out to the world, finally translated from Arabic into English, provide a record of the human condition.

In 2002—just after 9/11 and prior to the US invasion of Iraq—a group inspired by Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury’s NYU seminar on Arab prison literature decided to collectively translate Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar’s collection A Dove in Free Flight. Smuggled out of prison, the poems were published in Beirut without his knowledge, as a means of publicizing the poet’s plight as a political prisoner, and exerting pressure on public opinion to pay attention to his case. A French version, translated by the great Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laabi, himself a former political prisoner, followed. More than fourteen years after initial completion of the project, UpSet Press presents this extraordinary poetic, human, and historical document, featuring an introduction by editors Ammiel Alcalay and Shareah Taleghani, a preface by Elias Khoury, and a lengthy interview with the poet himself following his release on November 16, 2000, after thirteen years, seven months, and seventeen days in the Syrian carceral archipelago. We present Khoury’s introduction here, along with a selection of Bayrakdar’s poems. Publication date is March/April, 2021.

What Readers Are Saying

Beautiful and intensely emotional, Faraj Bayrakdar’s songs of memory, love, heartbreak and yearning are a testimony to the transformative power of the imagination.The Syrian prisons where his poems were written remain places of torture and violence. Yet during his long years of incarceration, the poet captured the elusive bird of freedom in poems smuggled out and published in Beirut and France without his knowledge, words that went on to inspire the Syrian revolution. The impressive collective of translators, writers and critics behind this first collection of Bayrakdar’s poetry in English were inspired by Elias Khoury’s seminar on Arab prison literature at New York University, and the explosive nature of this literature in a country as closed as Syria. In an interview accompanying the poems, Bayrakdar reveals, “… captivity and freedom … enfold in themselves a charge that does not fade, not for the reader and not for the poet.”

—Malu Halasa, co-editor of Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, and author of The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie: Intimacy and Design, and Mother of all Pigs.

Pre-order the book from Upset Press.

Faraj Bayrakdar’s poems, written while in prison, are a glorious testament to the power of the imagination and memory. Every page in this magnificent, important book is proof of how “language at the peak of clarity/unfolds the night,” how it transcends time and space to create its own kingdom, one where justice and love reign. Those searching for the right words to describe these turbulent days, and to offer hope, will find them here. Bayrakdar is a voice we must listen to, and this is a book that all of us must read.

—Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King, shortlisted for the Booker Prize

These searing and openhearted poems, born in prison, scrawled on cigarette paper, smuggled out from Assad’s repressive rule in Syria, and now finally translated from Arabic into English, make a fresh contribution to thought as much as to poetry. This thought is conservative in that it protects and preserves a poetics that live on under oppressive conditions. How rare it is to experience pride in being human in contrast to the depravity we have increasingly paraded in public. The prisoner, in mourning for life while that life continues outside, is the keeper of a buried treasure, thought itself and a bit of paper.

—Fanny Howe, poet, novelist and, most recently, author of Night Philosophy and Love and I.

Portrait of a Poet

Elias Khoury

At New York University where I taught a seminar on the prison in contemporary Arabic literature, I discovered, through a number of modern Arabic fictional and poetic texts, that the prison forms a basic trope in Arabic writing. In fictional texts of Abdelrahman Munif, Sonallah Ibrahim, Fadhil al-‘Azzawi, Bensalem Himmich, Naguib Mahfouz, and Gamal al-Ghitani among others, the prison takes on the mirror image of writing. Prison produces a literary approach that searches for writing and/or emancipation through writing. The literature engages in its own approach to the relationship of the experience of prison. It also establishes a balance between the desire for freedom and a writing that resembles a tattoo in its ability to engrave for itself a place in the body of the language. Literary Arabic writing is tattooed by prison. Perhaps the title that the Iraqi Abdelrahman al-Majid al-Rabi‘i chose for the novel about his experience in prison—The Tattoo—is the greatest indication of the deep wound that oppression and dictatorship have inscribed on the body of contemporary Arabic literature.

Among the tales and the tortured souls, a small collection of poems by the Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar made us pause; A Dove in Free Flight is a collection which the poet wrote during his long incarceration in Syrian prisons. His friends published it in Beirut without his knowledge so that the book could become one of the instruments of pressure on the authorities of his country and mobilize international, intellectual opinion, particularly in France, for the purpose of setting the poet free.

Both the interview with the poet that was published by Muhammad ‘Ali al-Atassi in the cultural supplement of Beirut’s daily al-Nahar, and the poems which abound with a dream and a despair made our readings of the poems a personal experience for each of us. The students chose poems in order to translate them into English. Through my attempts to help them fathom meanings and connotations, I discovered that the poetry—as the whisper of a language that approaches the terror of silence and eliminates the barriers between languages—was able to address the different levels of our consciousness and unconsciousness.

The poet wrote his poems with ink made from tea and onion peels using a thin wooden stick in place of a pen. From prison to prison and torture to torture, he takes us on his voyage to experience the connection between the body and the soul. The body is annihilated under the beatings or the electric shock or the “tire” or what has no end in the dictionary of Arab oppression whereas the soul protects, commiserates with, and shelters the body. This relationship resembles that of memory to writing; memory protected from oblivion the poems that Bayrakdar could not write down in Tadmor Prison. And when writing did come in Saydnaya Prison through ink that was not ink, it allowed memory to be liberated from the need for recollection and opened up the possibilities of forgetting.

In his prison, the poet appropriates all of Arabic poetry. It is as if he has granted his experience to a collective memory crafted from the images, rhythms, and forms accumulated in the Arabic language. Thus, we come across the tension of the language intertwined with the symbol as in the poetry of Darwish. Yet we also find Malik Bin al-Rayb as he attempts the echo of the dualism of Imru’ al-Qays who introduced tragedy into pre-Islamic poetry. When Imru’ al-Qays resorted to the dual form, he addressed his divided self as two halves—one half for mourning and the other for love. But when Bayrakdar further divided this dual form, he was searching for the soul that had been separated from both its own despair and the body that protected it from ruin.

Faraj Bayrakdar mingles love with poetry and despair with sorrow. He presents a personal experience about the story of an individual confronting terror and death. One becomes divided in order to merge others with his fragmentation, and the poet resorts to imagery of women and a daughter in order to reveal his body as a solitary, locked cell.

Faraj was arrested for the first time in 1978 for a period of three months because, along with comrades, including the late short story writer Jamil Hatmal, he published a small journal called “The Literary Notebooks.” Yet his journey in prisons began in 1987 with the accusation of political activities through his association with a small leftist party, the Communist Action Party in Syria. In the three prisons to which he was transferred—Palestine Division, then the horrifying Tadmor, and finally Saydnaya—the poet traversed a purgatory of sorrow, loneliness, and pain. He returned to poetry to retrieve the air that his lungs had lost; in Tadmor, he wrote the poems in his memory, and in Saydnaya, he recorded them and sent them to the outside. He discovered that poetry is not an articulation of experience but rather that poetry, itself, is an experience that grants the prisoner his freedom inside the damp, desolate cells.

In his poem “Hunger Strike” (Tadmor 1989) he reveals himself as a tree:

In the last part of night

of blood and memory

in the last neigh

of empty stomachs

the human tree reveals

its prophecy

and pours forth our meager

stature

In his poem “Neighing,” he discovers the relationship between the body and freedom:

for my prison cell is my body

and the ode incidental freedom

And then he takes us to a combination of passion and sorrow:

The blue of depth is sadness

and the depth of blue—sadness

and we are nothing but it.

Are we in its mirror,

or is it in ours?

Faraj’s journey has been long and difficult: for in his search for his threatened life and existence, he fashioned a personal song for freedom. The prisoner, himself, becomes a story because the prisoners’ freedom of expression and opinion in the Arab world becomes the only liberty in a time of oppression, dictatorship, and the absence of civil society.

A poet has given us words emanating from pain: his words proceed forward and then stumble resembling the embers of a scream of resistance combined with a cry for help:

I cry out

I am not searching for a collective grave

Just my country

When will the country hear you, poet? And when will the grave no longer be the only remaining space of the nation? — Elias Khoury

Translated by Shareah Taleghani

Three Poems from: A Dove in Free Flight

Faraj Bayrakdar

Two Verses

She doesn’t flutter like any butterfly

to stir his heart like a

pomegranate blossom —

It’s no one but him — so does he say to her:

Enough of your blue butterfly —

Enough of my craving to

be shoreless!!

* * *

Shadow rests on the trees

and memories on hard labor:

Neither are you the ruins for which I cry,

nor are the poets like me when they mourn.

The wind has cloaked me

after passing through the wheat:

wind — mistress of the fields

wind — mistress of the horses

wind — mistress of the reeds.

* * *

She doesn’t coo like any dove

moistening the sky —

oh god, my wife —

oh god, our daughter —

oh god, two fugitive gazelles

kiss my soul with two verses of dew

and race on —

Oh lightning,

shadow their steps —

Horizon,

take my heart and embrace them

so the deluge

might be delayed

Damascus/Palestine Division 1987

Assassination

The throne of the ode is a rose

who assassinates her maker

and serves him so he grants her speech

and if it is he she urges to go on he can get

to the farthest question like lightning broken

by the tale and the temptation

and the shadows

hurl a lightning bolt

and he can get the prophecy — all of it —

from the embers of the vision

to the woman of clouds

Tadmor Prison 1991

As Long As You Are, I Am

You can come in

without permission

and leave without permission

as long as my heart is open

and I can be your confession

as long as you are my forgiveness

Your question

still my answer

Your rains…

still my lightning

Your time…

still my place —

So do I have to apologize

if my fate is surrounded

by obscurity

and my life encircled in poetry?

Saydnaya 1993

Translated by the New York Translation Collective: Ammiel Alcalay, Sinan Antoon, Rebecca Johnson, Elias Khoury, Tsolin Nalbantian, Jeffrey Sacks, and Shareah Taleghani