Nektaria Anastasiadou reviews polyglot Tony Molho’s memoir about the Holocaust in Greece and his family history.

Courage and Compassion, a Jewish Boyhood in German-Occupied Greece, by Tony Molho

Berghahn Books 2024

ISBN 9781805394846

Nektaria Anastasiadou

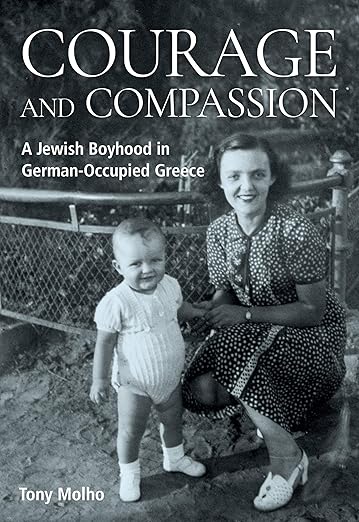

The day following an attempted sabotage of my second book (more on that later), I made a run for a few contemporary Greek novels to take back to Istanbul from Athens. I have a standard protocol for responding to bad will: I allow myself to be upset and shocked for a few minutes or hours, and then I redouble my efforts to surmount obstacles, write, and create more and better than before. That particular morning, I woke up feeling that the way forward was to connect with more writers, and so, after coffee, I went straight to a book shop in Akadimías Street, the closest to my hotel. Unfortunately, the place was in complete disorder, with shelves and tables pushed to the walls to make room for an afternoon event. The owner was busy with another customer, so my only choices were to wait for help or randomly browse the bits of the mess within reach. I chose the mess, and my glance immediately fell on a book with the black and white photo of a woman and her baby son. The title was H Κοινοτοπία του Καλού/The Banality of Good — a play on Hannah Arendt’s expression “the banality of evil” — by Antonis (Tony) Molho, an author unknown to me. The cover was wrapped in the red paper banner that denotes an award-winning Greek book (in this case, the 2023 Academy of Athens Ouranis Prize). I felt a visceral attraction to it even before I read the subtitle, which translates into English as “A Jewish Boyhood in Nazi-Occupied Greece.” I bought the memoir — recently released by Berghahn Books in English as Courage and Compassion — instead of the novels that I had come for.

On the subway ride to the airport, I became engrossed in Molho’s artful, palimpsestic narration, as well as his meditations on his family’s place in Ottoman and Greek history before, during, and after the Holocaust in Greece. The story begins with the arrival of Sephardic Jews in Ottoman Salonica in 1492; Salonica’s annexation by the nascent Greek state in 1913 (after which many Jews, including some of Molho’s relatives, migrated to Constantinople or westward to Europe or the Americas); and the end of the city’s four-century Jewish-majority status in 1922, when 160,000 Orthodox Christian refugees, forced by the Greco-Turkish Population Exchange to leave their homelands in Asia Minor, were relocated to the city.

Molho himself was born in Salonica in 1939. He has almost no memories of the city before the Nazi occupation in 1941 and few memories before his parents were forced to leave him in the care of a Christian family in 1943, so that they could flee southward and avoid deportation. Molho narrates his parents’ departure in a German army truck (the driver had been bribed), their hike over Mount Olympus, and finally their train trip from Larisa to Athens, during which his mother Lily was captured and made a miraculous escape by standing on the footboard outside the door of the moving train. Molho also recounts his own flight months later, during which the train engineer concealed him from the Nazis inside an empty boiler. Molho made it to Athens safely, but he was only briefly united with his parents before being hidden again in a Christian home with the help of the Catholic nuns of the Pamakáristos Monastery. Over the next two years, he would change houses and families numerous times. I won’t go into more details of this period so as not to spoil the dramatic storytelling, as suspenseful as any thriller, but also because the aftermath the war is the true heart of the book.

I have long been a fan of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s fictional portrayals of Holocaust survivors and the ways in which they carry the emotional burden of the Shoah. I was similarly entranced by Molho’s stories of post-Holocaust Greece and America. He engages not only with his parents’ memories and his own, but also with three versions of himself: the historian (he retired from Brown University in 2000 as the David Herlihy University Professor Emeritus and subsequently became a Professor of History and Civilization at the European University Institute); the older man looking backward upon his lifetime from a new century; and the small child caught up in the Shoah, unable to fully understand what is happening to and around him.

In 1945, after the Nazis left Greece, the erudite pianist Lily Molho (who had survived the occupation working as a servant in Athenian homes and later as an employee of the Red Cross), the merchant Saul Molho (who had spent a year and a half as a partisan in the mountains), and their six-year-old son, Tony Molho, reunited in Athens. They had barely grown used to each other again when Saul returned to Salonica/Thessaloniki in order to prepare the family home for his wife and child, to resurrect his business, and to resume the care of his elderly mother Flora, who, during the occupation, had hidden in the shack of a poor Christian woman, pretending (at least when Nazis searched the house) to be the woman’s deaf, mute, and senile aunt. During the months following Saul Molho’s return to Thessaloniki, Lily attempted to familiarize Tony with the grandparents and other relatives whom he would soon (re)meet by telling him stories of their former lives. Finally, in late Spring 1945, mother and son boarded a ship bound for their city (a land trip was too dangerous because of the Civil War that had broken out after the end of the occupation).

The arrival of Lily and Tony in Salonica seemed propitious: a sunny day, a back garden filled with blooming wisteria, a house intact albeit missing various things, including Lily’s beloved piano. Saul, Lily, and Flora broke down sobbing in each other’s arms, but still they were hopeful about a return to normality. In the coming weeks, they heard incredible stories of Jews being burned in Poland; they dismissed these stories as impossible rumors. But when relatives did not return and the rumors turned out to be true (45,000-50,000 Jews, 95% of Salonica’s Jewish community, had indeed been murdered), Lily, who had been fiercely determined and capable of astonishing heroism before and during the war, suffered a nervous breakdown and remained bedridden for months.

While his mother “struggled to come to terms with the empty spaces in her life,” Tony returned to school and joined neighborhood play groups, but not one of his Christian neighbors, teachers or classmates ever asked him the obvious: Tony, how did you survive? Certainly no one had forgotten that he was Jewish. His religion was written on his identity card; a boarding school classmate cursed at him, using a pejorative for Jew; and his favorite high school teacher told him that he would not be able to realize his dream of becoming a diplomat because, “They do not take Jews in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” The Greek Orthodox Christians of Thessaloniki, consequently, were neither interested in his experience nor willing to confront their active or passive complicity in the deportations of Jews. After all, the 1922 refugee influx had created a scarcity of housing. This, combined with antisemitic sentiment cultivated among Balkan Christian communities for centuries, led Christian locals and refugees alike to covet Jewish houses and enterprises, most of which passed into Christian hands during the Holocaust. As Molho writes:

The Shoah in its Salonican-Greek variant was consummated in a local context where intense rivalries between Christians and Jews were a constant presence in the city’s life. With the silencing of a strong Jewish voice as a consequence of the Shoah, after the war, much of the Jewish legacy to Salonica’s history was willfully forgotten. It was as if a huge sigh of relief was exhaled by the city’s population—perhaps one should better say that a collective fit of amnesia overtook the city’s leaders—intellectuals, secondary-school and university professors, public servants, newspaper editors and journalists, lawyers and notaries, doctors and pharmacists, not to speak of priests and bishops and other religious functionaries. Jews had now become a very, very small minority, from fifty, perhaps sixty, thousand to about two to three thousand people. Their properties, in circumstances that to this day have never been fully investigated, passed to the hands of Christians. Even the grounds of their cemetery—perhaps the largest Jewish one in Europe, larger it seems even than the one in Prague—had been assigned to the local university, where, for decades, rectors, deans, and faculty assemblies had stubbornly refused even to place a plaque commemorating the Jewish cemetery’s presence in that spot. One of my troubling memories of those immediate postwar years was the sight of slabs of marble, marked by strange signs—Hebrew letters!—found in the most unlikely spots in the city. These mutilated tomb stones, scattered about when the Jewish cemetery was vandalized—it should be added not by the Germans but by local municipal authorities—were put to all sorts of uses: as paving stones to decorate church yards, as building materials to construct street pavements and sidewalks, and, in at least one case, to firm up the walls of a swimming pool.

In recent years — now that the Jews of Greece are unthreateningly few and Jewish property transferal to Christians is unlikely to be contested — there has been a renewed interest in the minority. A plethora of books have been published portraying Jews in “painless, nostalgic fiction,” as Molho described in our correspondence after I contacted him with questions for this essay. Courage and Compassion (as Η Κοινοτοπία του καλού/The Banality of Good), was first released in Greek in 2022, despite having been written in English, because Molho had trouble finding an English-language publisher for it. The memoir not only received spectacular reviews in leading Greek publications Kathimerini and To Vima, but it also won a prestigious award from the Academy of Athens. Since the outbreak of the Israel-Gaza war, however, antisemitism has been increasing worldwide, and Jewish topics have once again fallen out of fashion. Two of Molho’s book talks, one in Greece and one in the United States, were cancelled with the excuse that the current time is not “appropriate.” This antisemitic tendency is something to which I can attest myself: despite numerous interviews about my Greek-language novel Στα Πόδια της Αιώνιας Άνοιξης/At the Feet of Eternal Spring, not one journalist has asked me about one of the novel’s most important themes: antisemitism.

The late Israeli rabbi and philosopher Adin Steinsaltz was known for saying that the most important question in life is “And then what?” (ואז מה/ve’az ma). He explained that it is easy to become excited about positive life changes such as a wedding or a Bat/Bar Mitzvah, but the truly important question is: what one will do after such markers? It seems to me that “And then what?” applies just as much to negativity — and even horrific events — as it does to weddings and graduations. I found Tony Molho’s memoir on a day when I was pondering what motivates people to harm or help others. The previous evening, I had attended my own novel’s presentation at an association that I prefer not to name. There, the association’s own presenter, who had up until that point feigned appreciation for my novel, engaged in a forty-minute linguistic lecture — despite having no linguistic training — during which he sadistically pointed out my supposed “errors” and even publicly requested that my publisher change my chapter titles because they “did not facilitate his research.” It was an outright attempt at sabotage and humiliation, which backfired on him when award-winning poet Krystalli Glyniadaki and I took the floor, spontaneously adding to our literary conversation a brief linguistic defense of the book. Afterward, the audience expressed to me their disgust with the presenter and his arrogant palaver (one elderly lady even congratulated me saying “Bravo, my girl, you’ve got balls!”).

The malicious presenter did not succeed in harming me or my book, but the question of why humans attempt to hurt each other — and how I could respond creatively to such — was on my mind when I picked up Molho’s memoir. On that day my “and then what?” was Courage and Compassion, a book that I might not had found without the upset of the previous night and a bookstore’s disorder; it was also a meeting with Molho himself a few months afterward in Athens, when I had the opportunity to chat with him over lemonade, seated beside fragrant mock orange trees in the middle of Varnáva Square. It turns out that Molho is not only a renowned historian, but a fascinating conversationalist and a kindred spirit who refuses, as I do, to tick a national or ethnic box. He discusses multilingualism and fluid national identities in his book as well, wondering if he and his family were Greeks who happened to be Jews or Jews who happened to live in Greece. To this day he steadfastly refuses to prioritize any country as a fatherland, although he belongs, in a way, to three — Greece, the United States, and Italy. Unlike the late novelist Mario Levi, who claimed that his fatherland was the Turkish language itself, Molho is also unable to single out one of his many languages as his maternal tongue:

As for me, it was Greek with my friends outside the house and with the household help, French with my parents, and Ladino with my grandmother, who could read only in Ladino, but then again only if it was written in Hebrew characters…I don’t remember any of us having any trouble shifting from one of these languages to another nor did we confuse one with the others. A sort of linguistic macédoine prevailed at home and in family gatherings, and it set us apart from neighbors and acquaintances whose monolingual regimens we, I mean my sister, cousins, and I, sometimes childishly envied. What, then, was our langue maternelle? By all accounts, it was that amalgam of languages that prevailed in our conversations at home.

Tony Molho’s Courage and Compassion is a brilliant memoir about the Shoah in Greece, its aftermath, and the author’s family’s attempt to continue creating and moving forward despite their tragedy. His story — and even our eventual acquaintance in Varnáva Square — became the unexpected afterward to the one of the strangest book talks I have ever given. The more general “and then what?” of antisemitism in Greece and worldwide remains to be written, but I believe that Dr. Molho and I will do our best not to let the problem be ignored.

I was a student at Brown university under Professor Anthony J. Molho some fifty years ago. I had no idea of his background until seeing a reference to his memoir in the Brown Alumni Magazine, mere days ago. I will do all I can to obtain a copy of his book, and if possible, resume the one-time correspondence I had with him about fifteen years ago.

What a story. It goes to show us all that we may have no idea of the story in the lives of others around us. Professor Molho’s life hung by threads as a small child amid the storms perpetrated by man’s inhumanity to our fellow man. I am grateful he grew up to be the scholar and teacher he has been. May his story never be lost.

What a book. What a story of humanity for a family and their small child in the midst of the Holocaust. I am grateful to have studied briefly under Professor Molho at Brown University some fifty years ago. I had no idea of his background story, and will do all I can to obtain a copy of his memoir.